Nanosurf IV: Traceable Measurement of Surface Texture at the Nanometre Level

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atomic Force Microscope for Planetary Applications T

ATOMIC FORCE MICROSCOPE FOR PLANETARY APPLICATIONS T. Akiyama, S. Gautsch, N.F. de Rooij,U. Staufer Institute of Microtechnology, Univ.of Neuch8te1, Jaquet-Droz 1,2007 Neuchatel, Switzerland. Ph. Niedermann CSEM, Jaquet-Droz 1,2007 NeucMtel , Switzerland. L. Howald, and D. Miiller Nanosurf AG, Austrasse4,4410 Liestal, Switzerland. A. Tonin, and H.-R Hidber Insitute of Physics, Univ. of Basel, Klingelbergstr.82 4056 Basel, Switzerland W. T. Pike, M. H. Hecht Jet Propulsion Laboratory, CaliforniaInstitute of Technology, 4800 Oak Grove Dr. Pasadena, CA91 109, USA ABSTRACT will be sent to Mars in the next three years, contains a microscopy station to produceimages of dustand soil particles. Mars Wehave developed, built and tested an atomicforce Pathfinder data indicates that the mean particle size of Martian microscope (AFM) for planetary science applications, inparticular atmosphericdust is less than 2 micrometers.Hence MECA's for the study of Martian dust and soil. The system consists of a microscopy station, in addition toan optical microsope capable of controller board, anelectromagnetic scanner and micro-a taking color and ultraviolet fluorescent images, includes an AFM fabricatedsensor-chip. Eight cantilevers withintegrated, to image far below optical resolution (fig. 1). The sample-handling piezoresistivedeflection sensors are alignedin a row and are system consists of an external robot arm, for delivery of surface engaged one after the otherto provide redundancy in case of tip or and subsurface soil samples, and a two-degree-of-freedom stage. cantilever failure. Silicon and molded diamond tips are used for The stage contains 69 substrates that can be rotated in turn to the probing the sample. -

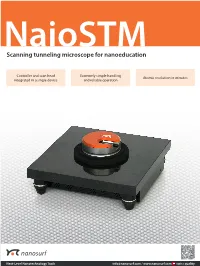

Scanning Tunneling Microscope for Nanoeducation

NaioSTM Scanning tunneling microscope for nanoeducation Controller and scan head Extremely simple handling Atomic resolution in minutes integrated in a single device and reliable operation Next-Level Nanotechnology Tools [email protected] / www.nanosurf.com swiss quality NaioSTM Your easy entry into the world of atoms The first scanning tunneling microscope (STM) was developed in 1981 by Binnig and Rohrer at the IBM Research Laboratory in Rüschlikon, Switzerland, for the first time making atoms directly visible to a small group of specialists. In 1997, Nanosurf went one step further and brought atoms to the classroom! Today, well over a thousand Nanosurf STMs play a crucial role in nanotechnology education around the globe: Atomic lattices. Left: Graphite (HOPG), • Teachers appreciate the ease of use of Nanosurf STMs, allowing them to offer quick scan size 2 nm. Right: MoS2, scan size and hassle-free classroom demonstrations to their students. 3 nm. • Students are motivated by the rapid successes achieved when using the STMs themselves during hands-on training. • Anyone can safely handle a Nanosurf STM, since STM tips are simply cut from Pt/Ir wire without requiring etching in hazardous substances. The NaioSTM is the successor to the well-known Easyscan 2 STM and brings together scan head and controller in a single instrument for even greater ease of installation, usability, and transportability. The whole setup is very resistant to vibrations and can Step heights. Left: Gold, scan size be used to achieve atomic resolution on HOPG in standard classroom situations. 500 nm. Right: YBCO, scan size 180 nm. Place your sample.. -

Nano-Images from Mars

News From: Issue: September Nano-images from Mars Nanostructures were measured on another planet for the first time on 9th July when the NASA Phoenix Mars Probe recorded images with nanometre resolution using its onboard Swiss-made atomic force microscope, and successfully transmitted them back to Earth. The first images of the microscope – which was developed by the universities of Neuchâtel and Basel, and by the Swiss company Nanosurf – show the surface of a test grid with unprecedented detail. The successful imaging of this test grid served as a calibration for the nano-microscope and documents full functionality of the instrument. “The operation of our atomic force microscope under these harsh conditions demonstrates the suitability for daily use of such nano-imaging devices,” said Nanosurf Mars project leader Dominik Braendlin. “We are now anxiously awaiting the upcoming images of Mars surface particles". The Phoenix Mars probe is scheduled to investigate the shape and structure of Mars dust and soil particles. Their surfaces – when documented with the proper resolution – harbour a wealth of scientific data. Erosion and scratch marks on these particles, for instance, can give crucial clues as to whether the particles were ever transported by liquid water on Mars. The resolution required for this task is only attained by the atomic force microscope. In contrast to optical microscopes, this nano-imaging device touches the surface of the particles to be analyzed with a very sharp tip, recording surface height information in a scanning-type motion. The Nanosurf atomic force microscope is part of the MECA (Microscopy, Electrochemistry, and Conductivity Analysis) unit – one of seven on the Phoenix Mars probe – which has been providing NASA with scientific data from the very start of its deployment. -

Nanosurf Easyscan 2 STM Operating Instructions

Operating Instructions easyScan 2 STM Version 1.6 ‘NANOSURF’ AND THE NANOSURF LOGO ARE TRADEMARKS OF NANOSURF AG, REGIS- TERED AND/OR OTHERWISE PROTECTED IN VARIOUS COUNTRIES. © MAY 07 BY NANOSURF AG, SWITZERLAND, PROD.:BT02090, V1.6R0 Table of contents The easyScan 2 STM 9 Features...............................................................................................10 easyScan 2 Controller 10 Components of the system..................................................................12 Contents of the Tool set 14 Connectors, Indicators and Controls ...................................................15 The Scan head 15 The Controller 15 Installing the easyScan 2 STM 18 Installing the Hardware........................................................................18 Installing the Basic STM Package 18 Installing the Signal Module: S 19 Installing the Signal Module: A 19 Turning on the Controller 19 Storing the Instrument .........................................................................20 Installing the Software .........................................................................20 Step 1 - Installation of hardware drivers 22 Step 2 - Installation of the easyScan 2 software 28 Step 3 - Installation of DirectX 9 29 Installing the software on different computers 29 Preparing for Measurement 30 Initialising the Controller ......................................................................30 Preparing and installing the STM tip....................................................30 Installing the sample............................................................................33 -

Scanning Tunneling Microscopy (STM) Was Developed by Gerd Binnig and Heinrich Rohrer in the Early 80’S at the IBM Research Laboratory in Rüschlikon, Switzerland

Scanning Probe Microscopy 2008 IF1602 Materialfysik för E Pål Palmgren Niklas Elfström 2006 Scanning Probe Microscopy (SPM) Scanning probe microscopy (SPM) is the name for a class of microscopy techniques that offers spatial resolution down to a few Ångströms. This extreme resolution has led to a new understanding of the structure of materials and forms of life. With the help of scanning probe microscopy it is possible to look into the fascinating world of the atoms. SPM works without optical focusing elements, instead a sharp probe tip is scanned across a surface and probe-sample interactions are monitored to create an image of the surface. There are basically two types of microscopes, scanning tunnelling microscopy (STM) and atomic force microscopy (AFM). Scanning Tunneling Microscopy (STM) was developed by Gerd Binnig and Heinrich Rohrer in the early 80’s at the IBM research laboratory in Rüschlikon, Switzerland. For this revolutionary innovation Binnig and Rohrer were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1986. In STM, a small sharp conducting tip is scanned across the sample’s surface, so close that a tunnel current can flow. With the help of that current the tip-surface distance can be controlled with such precision that the atomic arrangement of metallic or semiconducting surfaces can be determined. STM is restricted to electrically conducting surfaces. A further development of STM called Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) was developed by Gerd Binnig, Calvin Quate and Christoph Gerber. AFM extends the abilities of the STM to include electrically insulating materials. Instead of measuring a tunnel current atomic-range forces between tip and sample surface are measured. -

Scanning Probe Microscopy

Scanning Probe Microscopy Thilo Glatzel Department of Physics University of Basel [email protected] -Scanning tunneling microscopy -Force microscopy under ultrahigh vacuum conditions -Molecular electronics National Center of Competence in Research Nanoscale Science http://www.nccr-nano.org What do scientists mean by Nanoscience? Prefix “nano”: one billionth of something like a second or a meter. 1 nm = 1 billionth of a meter 1mm 1 nm = 1 millionth of a millimeter How large? 12‘740‘000m 0.22m 1nm 0.3nm : 57‘909‘090 : 220‘000‘000 Scanning Tunneling Microscopy (STM) xyz-Piezo-Scanner z high voltage y amplifier x probing tip I feed-back regulator sample Feed-back regulator keeps current (pA-nA) constant. Contours of constant current are recorded. Quantum tunneling Quantum mechanical tunneling classical −d = ⋅ κ It U e κ≈ It=1nA U=1V 0.1nm quantum mechanical: Tunneling current J. Frenkel, Phys. Rev. B 36, 1604 (1930) Invention of the Scanning Tunneling Microscope (STM) G. Binnig and H. Rohrer Nobel prize for physics 1986 IBM Rüschlikon Switzerland Source: IBM Steps at a Silicon single crystal surface. Si(111)7x7 reconstructed surface 48 Fe-atoms on copper (Quantum corral) D. Eigler, IBM Almaden Fe atoms on copper STM for Scools Nanosurf AG, Liestal: Start-up from the University of Basel Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) 40 µ m Laser- beam Detector tip Sample Scanner Principle of Atomic Force Microscope (AFM) deflection sensor cantilever feed-back probing tip regulator sample high-voltage xy-piezo (lateral position) amplifier z-piezo (tip-sample distance) Commercial AFMs Veeco, US Nanosurf, Liestal, CH Ultrahigh vacuum force microscope with in-situ preamplifier and stabilized light source • UHV- chamber with base pressure < 10 -10 mbar • room temperature • Fast in-situ preamplifier (<3MHz) Ultra-sensitive non-contact force microscope combined with STM NaCl-crystal True atomic resolution NaCl(001) (Insulator surface with point defects) 10 min 70 min 110 min M. -

Magnetic Force Microscopy (MFM)

Magnetic Force Microscopy (MFM) Magnetic force microscopy (MFM) is one of obtained when the magnetic moments of the modes of scanning probe microscopy tip and sample are parallel. This results in (SPM). As the name suggests, it is used for the resonance curve shifting to a lower mapping magnetic properties. MFM probes frequency, accompanied by a decrease in local magnetic fields on the nanoscale, phase shift at the excitation frequency resulting in images that contain (Fig. 1). Conversely, a repulsive magnetic information on a sample’s localized force gradient by anti-parallel orientation magnetic properties including the mapping of the magnetic moments will cause the of magnetic domains and walls. It is resonance curve to shift to a higher primarily a qualitative, contrast-based frequency, accompanied by an increase in technique and has been widely used to phase shift at the excitation frequency. The characterize magnetic storage media, cantilever predominantly responds to out- superconductors, magnetic nanomaterials, of-plane fields. and even biological systems. Magnetic forces acting on the cantilever by the sample are measured as the tip is lifted How does it work? off the surface thus separating the long- range magnetic forces from the short- MFM operates in dynamic force mode with range atomic forces between tip and phase contrast. A cantilever with a thin sample. The tip-sample distance is a crucial magnetic coating is driven near its parameter to optimize for effective MFM resonance frequency f0, where you have a operation. If the tip is too far from the 180° phase shift going from below to above sample, the resolution will be the resonance frequency. -

Scanning Tunneling Microscopy

Scanning Tunneling Microscopy Nanoscience and Nanotechnology Laboratory course "Nanosynthesis, Nanosafety and Nanoanalytics" LAB2 Universität Siegen updated by Jiaqi Cai, April 26, 2019 Cover picture: www.nanosurf.com Experiment in room ENC B-0132 AG Experimentelle Nanophysik Prof. Carsten Busse, ENC-B 009 Jiaqi Cai, ENC-B 026 1 Contents 1 Introduction3 2 Surface Science4 2.1 2D crystallography........................4 2.2 Graphite..............................5 3 STM Basics6 3.1 Quantum mechanical tunneling.................7 3.2 Tunneling current.........................9 4 Experimental Setup 12 5 Experimental Instructions 13 5.1 Preparing and installing the STM tip.............. 13 5.2 Prepare and mount the sample................. 15 5.3 Approach............................. 16 5.4 Constant-current mode scan................... 17 5.5 Arachidic acid on graphite.................... 18 5.6 Data analysis........................... 20 6 Report 21 6.1 Exercise.............................. 21 6.2 Requirements........................... 21 2 1 Introduction In this lab course, you will learn about scanning tunneling microscopy (STM). For the invention of the STM, Heinrich Rohrer and Gerd Binnig received the Nobel prize for physics 1986 [1]. The STM operates by scanning a con- ductive tip across a conductive surface in a small distance and can resolve the topography with atomic resolution. It can also measure the electronic properties, for example the local density of states, and manipulate individ- ual atoms or molecules, which are adsorbed on the sample surface. Some examples are shown in Figure1. Figure 1: a) Graphene on Ir(111), Voltage U=0.1V; Current I=30nA [2], b) NbSe2 (showing atoms and a charge density wave (CDW)) [3], c) manipu- lation of Xe atoms on Ni(110). -

The Most Flexible AFM for Life Science Research Versatile Research AFM for Life Science

Next-Level Nanotechnology Tools swiss quality Flex-Bio The most flexible AFM for life science research Versatile research AFM for life science For success in life science research, scientists depend on pro- fessional tools that can readily provide the information needed, regardless of the tasks at hand. By combining key technologies and components, Nanosurf has made the Flex-Bio system one of the most versatile and flexible AFM systems ever, allowing a large variety of biological and life science applications to be handled with ease. Key features & benefits Compatible with inverted microscopes Flat and linear scanning thanks to flexure-based scanner tech- nology True flexibility with exchangeable cantilever holders for specia- lized tasks More measurement versatility with the FlexAFM’s scanning ca- pabilities in liquid and its additional measurement modes Single molecule force spectroscopy of bacterio- rhodopsin. The force–distance curve reports the controlled C-terminal unfolding of a single membrane protein from its native environment, Unfiltered overview image with linear background Power spectrum of the crystal latice, showing a the purple membrane from Halobacterium sali- correction. Scan size: 140 nm. Inset: Correlation lateral resolution well beyond narium. Solid and dashed orange lines represent average, with 3 trimers highlighted in white. 1 nm (dashed white circle). the WLC curves corresponding to the major and minor unfolding peaks observed upon unfolding BR, respectively. FluidFM®add-on: nanomanipulation and ANA add-on: Automated nanomechani- single-cell biology cal data acquisition and analysis FluidFM® probe microscope (FPM) combines the force sen- ANA - Automated Nanomechnical Analysis - is designed to sitivity and positional accuracy of the Nanosurf FlexAFM with investi gate the nanomechanical properties of materials such as FluidFM® technology by Cytosurge to allow a whole range of cells, tissues, scaffolds, hydrogels, and polymers on multiple or exciting applications in single-cell biology and nanoscience. -

The Best-Selling Tabletop STM Your Easy Entry Into the World of Atoms

Next-Level Nanotechnology Tools swiss quality NaioSTM The best-selling tabletop STM Your easy entry into the world of atoms The NaioSTM is a scanning tunneling microscope that brings together scan head and controller in a single instru- ment for even simpler installation, maximized ease of use, and straightforward transportability. The setup is robust against vibrations and can be used to achieve atomic resolu- tion on HOPG in standard classroom situations. With its 204 × 204 mm footprint it hardly takes up any workbench space. Over more than 20 years and three development generati- ons, Nanosurf‘s scanning tunneling microscope has become the number one STM solution in the field. Because of its clever composition, it is widely regarded as the logical choice for per- forming scanning tunneling microscopy in all kinds of educatio- nal settings and basic research, with almost 1500 instruments in operation around the world (including the NaioSTM‘s predeces- sor, the Easyscan STM). The smart and purposeful design is perfectly suited to the needs of educational institutions: the system integrates scan head, controller, air-flow shielding with a magnifying glass to aid the initial approach, and vibration isolation on a heavy stone table. The additional passive vibration isolation feet further protect measurements against disturbances, making the system very robust during operation. The system functions without high vol- tage, making it safe in unexperienced hands. <10 mm mechanical loop The very small mechanical loop of <10 mm provides the stability to achieve atomic resolution on a coffee table or in a class room. See atoms in 5 minutes From unboxing to seeing atoms, only four simple steps are required: after con- necting the NaioSTM to the laptop on your workbench, prepare the probe by cutting off a piece of Pt/Ir wire. -

Introduction to Scanning Probe Microscopy

WORKSHOP Nanoscience on the Tip Introduction to Scanning Probe Microscopy Table of Contents: 1 Historic Perspectives .......................................................................................................................... 1 2 Scanning Force Microscopy (SFM) ................................................................................................... 2 2.1. Contact Mode .............................................................................................................................. 2 2.2. AC Mode Imaging....................................................................................................................... 3 2.3. Applied Force: Cantilever Deflection and Hooke’s Law ............................................................ 3 2.4. SFM Tips..................................................................................................................................... 4 3 Dip-Pen Nanolithography (DPN) ....................................................................................................... 7 References ............................................................................................................................................. 8 1. Historic Perspectives In 1982, Gerd Binnig and Heinrich Rohrer of IBM in Rüschlikon (Switzerland) invented scanning tunneling microscopy (STM). Although STM is not the focus of this lab, it is the ancestor of all the variations of scanning probe microscopy (SPM) that followed: although the mechanism of image contrast may vary, -

Sample Kit Manual.Book

User Manual Extended Sample Kit 1 ‘NANOSURF’ AND THE NANOSURF LOGO ARE TRADEMARKS OF NANOSURF AG, REGIS- TERED AND/OR OTHERWISE PROTECTED IN VARIOUS COUNTRIES. © 29.8.07 BY NANOSURF AG, SWITZERLAND, PROD.:BT0????, R0 2 Table of contents A Brief Introduction to Atomic Force Microscopy 7 Introduction ........................................................................................... 7 The AFM Setup..................................................................................... 8 The Force Sensor 9 The Position Detector 11 The PID Feedback System 12 AFM Operation Modes 15 The Scanning System and Data Collection 16 Chip Structure in Silicon 19 Measurements .................................................................................... 19 Image Acquisition 19 Image Analysis 20 Integrated Circuit Technology ............................................................. 22 Transistors 22 Integrated circuit production 25 Sample Maintenance .......................................................................... 27 CD Stamper 29 Measurement ...................................................................................... 29 Image Acquisition 29 Image Analysis 30 Optical Data Storage........................................................................... 31 Sample Maintenance .......................................................................... 34 Gold Clusters 37 Measurement ...................................................................................... 37 Image Acquisition 37 Image Analysis 38 Fabrication