Fayetteville and Raleigh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tennessee State Library and Archives WASHINGTON FAMILY PAPERS

State of Tennessee Department of State Tennessee State Library and Archives 403 Seventh Avenue North Nashville, Tennessee 37243-0312 WASHINGTON FAMILY PAPERS, 1796-1962 Processed by Harry A. Stokes Accession numbers: 83-001; 84-001; 89-131 Microfilm accession number: Mf. 961 Dates completed: Jan. 24, 1983; Mar. 16, 1984 Locations: XVII-F-K-1; VI-C-1v; oversize flat storage - top of map cases The Washington Family Papers, 1796-1962, are centered around “Wessyngton,” the Washington family home built in 1818 by Joseph Washington, tobacco planter, near Cedar Hill in Robertson County, Tennessee. The papers contain records of the plantation as well as the correspondence of four generations: Joseph Washington (1770-1848), tobacco planter; George Augustine Washington (1815-1892), tobacco planter, railroad executive, and capitalist; Joseph Edwin Washington (1851-1915), Congressman and tobacco farmer; and George Augustine Washington (1879- 1964), attorney, tobacco farmer, and genealogist. The papers were gifts of Mrs. Mary Kinsolving, Baltimore, Md.; Hickman Price, Jr., Palm Beach, Fla.; and Mrs. Anne K. Talbott, Cookeville, Tenn. Linear feet of shelf space occupied: 64 Approximate number of items: ca. 11,200 Single photocopies of unpublished writings in the Washington Family Papers may be made for purposes of scholarly research. WASHINGTON FAMILY PAPERS , 1796-1962 7/if. 91/ Microf1lm Container List Reel No . : 1. Box 1, folder 1 to Box 2, folder 10 2. Box 2, folder 11 to Box 5 , folder 9 3. Box 5, folder 10 to Box 8 , folder 8 4. Box 8. folder 9 to Box 10, folder 16 5. Box 10, folder 17 to Box 13, folder 18 6. -

![CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8733/chairmen-of-senate-standing-committees-table-5-3-1789-present-978733.webp)

CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present

CHAIRMEN OF SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–present INTRODUCTION The following is a list of chairmen of all standing Senate committees, as well as the chairmen of select and joint committees that were precursors to Senate committees. (Other special and select committees of the twentieth century appear in Table 5-4.) Current standing committees are highlighted in yellow. The names of chairmen were taken from the Congressional Directory from 1816–1991. Four standing committees were founded before 1816. They were the Joint Committee on ENROLLED BILLS (established 1789), the joint Committee on the LIBRARY (established 1806), the Committee to AUDIT AND CONTROL THE CONTINGENT EXPENSES OF THE SENATE (established 1807), and the Committee on ENGROSSED BILLS (established 1810). The names of the chairmen of these committees for the years before 1816 were taken from the Annals of Congress. This list also enumerates the dates of establishment and termination of each committee. These dates were taken from Walter Stubbs, Congressional Committees, 1789–1982: A Checklist (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985). There were eleven committees for which the dates of existence listed in Congressional Committees, 1789–1982 did not match the dates the committees were listed in the Congressional Directory. The committees are: ENGROSSED BILLS, ENROLLED BILLS, EXAMINE THE SEVERAL BRANCHES OF THE CIVIL SERVICE, Joint Committee on the LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LIBRARY, PENSIONS, PUBLIC BUILDINGS AND GROUNDS, RETRENCHMENT, REVOLUTIONARY CLAIMS, ROADS AND CANALS, and the Select Committee to Revise the RULES of the Senate. For these committees, the dates are listed according to Congressional Committees, 1789– 1982, with a note next to the dates detailing the discrepancy. -

Did You Know? North Carolina

Did You Know? North Carolina Discover the history, geography, and government of North Carolina. The Land and Its People The state is divided into three distinct topographical regions: the Coastal Plain, the Piedmont Plateau, and the Appalachian Mountains. The Coastal Plain affords opportunities for farming, fishing, recreation, and manufacturing. The leading crops of this area are bright-leaf tobacco, peanuts, soybeans, and sweet potatoes. Large forested areas, mostly pine, support pulp manufacturing and other forest-related industries. Commercial and sport fishing are done extensively on the coast, and thousands of tourists visit the state’s many beaches. The mainland coast is protected by a slender chain of islands known as the Outer Banks. The Appalachian Mountains—including Mount Mitchell, the highest peak in eastern America (6,684 feet)—add to the variety that is apparent in the state’s topography. More than 200 mountains rise 5,000 feet or more. In this area, widely acclaimed for its beauty, tourism is an outstanding business. The valleys and some of the hillsides serve as small farms and apple orchards; and here and there are business enterprises, ranging from small craft shops to large paper and textile manufacturing plants. The Piedmont Plateau, though dotted with many small rolling farms, is primarily a manufacturing area in which the chief industries are furniture, tobacco, and textiles. Here are located North Carolina’s five largest cities. In the southeastern section of the Piedmont—known as the Sandhills, where peaches grow in abundance—is a winter resort area known also for its nationally famous golf courses and stables. -

The North Carolina Historical Review

The North Carolina Historical Review Volume XIV April, 1937 Number 2 CHILD-LABOR REFORMS IN NORTH CAROLINA SINCE 1903 By Elizabeth Huey Davidson In 1903 North Carolina adopted its first child-labor law. It was a weak measure, forbidding the employment of children un- der twelve in factories, establishing a maximum of sixty-six hours a week for persons under eighteen, and providing no machinery for enforcement of the law. The passage of this measure had resulted from a slow growth of sentiment against the evils of child labor, and its terms represented a compromise between the reformers and the cotton manufacturers of the State. There was no organization to push further legislation, however, until the formation of the National Child Labor Com- mittee in 1904. This committee was largely inspired by the work of Dr. Edgar Gardner Murphy of Montgomery, Alabama, and had at first a number of prominent Southerners on its mem- bership roll. For its Southern secretary the committee chose Dr. Alexander J. McKelway, a Presbyterian clergyman of Char- lotte, North Carolina. The law of 1903 had been in effect a year when the committee attempted to reopen the drive for legislation. Its effectiveness in that length of time cannot be judged accurately, since the re- port of the Commissioner of Labor for 1904 fails to record the number of children employed in manufacturing. 1 The general consensus of opinion expressed by the manufacturers to the com- missioner was that the law should be accepted in good faith, but that it should also be the last one of its kind. -

The North Carolina Historical Review

THE NORTH CAROLINA HISTORICAL REVIEW JULY 1958 Volume XXXV Number 3 Published Quarterly By State Department of Archives and History Corner of Edenton and Salisbury Streets Raleigh, N. C. THE NORTH CAROLINA HISTORICAL REVIEW Published by the State Department of Archives and History Raleigh, N. C. Christopher Crittenden, Editor David Leroy Corbitt, Managing Editor ADVISORY EDITORIAL BOARD Frontis Withers Johnston Hugh Talmage Lefler George Myers Stephens STATE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHIVES AND HISTORY EXECUTIVE BOARD McDaniel Lewis, Chairman James W. Atkins Josh L. Horne Gertrude Sprague Carraway William Thomas Laprade Fletcher M. Green Herschell V. Rose Christopher Crittenden, Director This revieiv was established in January, 1924, as a medium of publica- tion and discussion of history in North Carolina. It is issued to other institutions by exchange, but to the general public by subscription only. The regular price is $3.00 per year. Members of the North Carolina Literary and Historical Association, Inc., for which the annual dues are $5.00, receive this publication without further payment. Back numbers may be procured at the regular price of $3.00 per volume, or $.75 per number. Cover: The Kivett Building of Campbell College (originally Buie's Creek Academy) is presently used as a science classroom and student supply store. This was the first building erected after the fire in 1900 and served as the administration building until 1926. It was named for Z. T. Kivett, who burned the bricks bought with "nickels and dimes." The photograph is by the cour- tesy of Mr. Claude F. Gaddy, Baptist State Convention. For a further study of early Baptist high schools and academies see pages 316-327. -

Good Old Days? Discovery Tour

e Good Old Days? Discovery Tour Resource Manual A compendium of classroom activities and resource materials to help you prepare for your Discovery Tour Who Was Here in 1860? On the eve of the American Civil War, North Carolina was a rural state with a total population of 992,622. Most citizens had been born in North Carolina and farmed for a living. Less than 1 percent of the state’s population in 1860 was foreign born, and about 70 percent of white families owned no slaves. Nevertheless, African Americans composed approximately one-third of the total population, and the majority were slaves. Few urban commercial centers existed, and Wilmington, the largest town, had fewer than 10,000 citizens. Yeoman Famers The majority of North Carolinians in 1860 were white subsistence farmers who worked small farms, 50 to 100 acres, and owned fewer than 20 slaves. They were more concerned with rainfall, crops, and seasonal changes for planting and harvesting than with national politics. They produced most of what they consumed and relied on the sale of surplus crops for money to buy what they could not grow or make by hand on their farms. These men would constitute the bulk of North Carolina’s army in the coming war. Planters Individuals who owned 20 or more slaves were considered planters. Most North Carolina planters lived in the Coastal Plain and Piedmont regions of the state, where conditions favored large-scale farming. Although they made up a minority, these individuals exercised political influence far greater than their actual number when compared to families with few or no slaves. -

Washington City, 1800-1830 Cynthia Diane Earman Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School Fall 11-12-1992 Boardinghouses, Parties and the Creation of a Political Society: Washington City, 1800-1830 Cynthia Diane Earman Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Earman, Cynthia Diane, "Boardinghouses, Parties and the Creation of a Political Society: Washington City, 1800-1830" (1992). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 8222. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/8222 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOARDINGHOUSES, PARTIES AND THE CREATION OF A POLITICAL SOCIETY: WASHINGTON CITY, 1800-1830 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History by Cynthia Diane Earman A.B., Goucher College, 1989 December 1992 MANUSCRIPT THESES Unpublished theses submitted for the Master's and Doctor's Degrees and deposited in the Louisiana State University Libraries are available for inspection. Use of any thesis is limited by the rights of the author. Bibliographical references may be noted, but passages may not be copied unless the author has given permission. Credit must be given in subsequent written or published work. A library which borrows this thesis for use by its clientele is expected to make sure that the borrower is aware of the above restrictions. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Party Formation in the United States a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of Th

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Party Formation in the United States Adissertationsubmittedinpartialsatisfactionofthe requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science by Darin Dion DeWitt 2013 c Copyright by Darin Dion DeWitt 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Party Formation in the United States by Darin Dion DeWitt Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Thomas Schwartz, Chair This dissertation is about how political parties formed in the world’s first mass democracy, the United States. I trace the process of party formation from the bottom up. First, I ask: How do individuals become engaged in politics and develop political affiliations? In most states, throughout the antebellum era, the county was the primary unit of political admin- istration and electoral representation. Owing to their small size, contiguity, and economic homogeneity, I expect that each county’s active citizens will form a county-wide governing coalition that organizes and dominates local politics. Second, I ask: Which political actor had incentives to lure county organizations into one coalition? I argue that the institutional rules for electing United States Senators – indirect election by state legislature – induced prospective United States Senators to construct a majority coalition in the state legislature. Drawing on nineteenth century newspapers, I construct a new dataset from the minutes of political meetings in three states between 1820 and 1860. I find that United States Senators created state parties out of homogeneous counties. They encouraged cooperation among county-wide governing coalitions by canvassing annual county political meetings, drafting ii and revising a multi-issue policy platform that had the potential to unite a majority of the state’s county governing coalitions, encouraging individual counties to create county- wide committees of correspondence and vigilance, and, finally, organizing a permanent state central committee and regular state-wide conventions. -

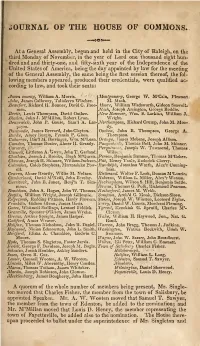

Journals of the Senate and House of Commons of the General Assembly

: . JOURNAL OF THE HOUSE OF COMMONS S. ®ft«< At a General Assembly, begun and held in the City of Raleigh, on the third Monday of November, in the year of Lord one thousand eight hun- dred and and thirty-one, and fifty-sixth year of the Independence of the United States of America, being the day appointed by law for the meeting of the General Assembly, the same being the first session thereof, the fol- lowing members appeared, produced their credentials, were qualified ac- cording to law, and took their seats Anson county, William A. Morris. Montgomery^ George W. M'Cain, Pleaaani Ashe, James Calloway, Taliaferro Witcher. M. Mask. JBeaufort, Richard H. Bonner, David C. Free- •i'Joore, William Wadsworth, Gideon Seawall, man. JVash, Joseph Arrington, George Boddie. J3ertis, Lewis Thompson, David Outlaw^ jYexv Hanover, Wm. S. Larkins, William J. Bladen, John J. M'Millan, Robert Lyon. Wright. Jirnnstvick, John P. Gause, Sam'l A. Las- JYorthampton, Richard Crump, John M. Moo- ycyre. dy. Buncombe, James Brevard, JohnClaytoa. Onslo-M, John B. Thompson, George A., Burke, Alney Burgin, Francis P. Glass. Tho.Tipson. Cabarnts, Dan'l M. Barringer, Wra. M'Lean Oratige, lames IMebane, Joseph Allison. Camden, Thomas Dozier, Abner H. Grandy, Pasquot.nJ:-, Thomas Bell, John M. Skinner. Carteret, Perqiiivi'jui, Joseph Tcwnsend, , W. Thomas . Cas-well, Littleton A. Uwj'n, JohnT. Garland, VVilso.i. Chatham, Joseph J. Brooks, Hugh M'Qaeen. Person, Benjamin Sumner, Thomas M'Gehee. Chowan, Joseph li. Skinner, William Jackson. Pitt, Henry Toole, Roderick Cherry. Columbus, Caleb Stepheas, Marriiaduke Pow Eandol/jh, Jonathan Worth, Alex'r Cunning- ell. -

Records of Ante-Bellum Southern Plantations from the Revolution Through the Civil War

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of RECORDS OF ANTE-BELLUM SOUTHERN PLANTATIONS FROM THE REVOLUTION THROUGH THE CIVIL WAR Series J Selections from the Southern Historical Collection, Manuscripts Department, Library of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Part 8: Tennessee and Kentucky UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of Records of Ante-Bellum Southern Plantations from the Revolution through the Civil War General Editor: Kenneth M. Stampp Series J Selections from the Southern Historical Collection, Manuscripts Department, Library of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Part 8: Tennessee and Kentucky Associate Editor and Guide Compiled by Martin Schipper A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Records of ante-bellum southern plantations from the Revolution through the Civil War [microform] Accompanied by printed reel guides, compiled by Martin Schipper. Contents: ser. A. Selections from the South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina (2 pts.) -- [etc.] --ser. E. Selection from the University of Virginia Library (2 pts.) -- -- ser. J. Selections from the Southern Historical Collection Manuscripts Department, Library of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (13 pts). 1. Southern States--History--1775–1865--Sources. 2. Slave records--Southern States. 3. Plantation owners--Southern States--Archives. 4. Southern States-- Genealogy. 5. Plantation life--Southern States-- History--19th century--Sources. I. Stampp, Kenneth M. (Kenneth Milton) II. Boehm, Randolph. III. Schipper, Martin Paul. IV. South Caroliniana Library. V. South Carolina Historical Society. VI. -

Hamrick Generations

THE HAMRICK GENERATIONS BEING A GENEALOGY OF THE HAMRICK FAMILY BY S. C. JONES SHELBY, N. C. 1920 8oWARDS & BROUGHTON PRINTING Co. RALEIGH, N. c. DEDICATION To the memory of my loving mother, who departed this life on March 1, 1887, at whose knees I sat as a child and listened to many a recountal of the heroic struggles and vicissitudes of her early Hamrick ancestors whose exploits and undertakings account, in a large measure, for the sterling citizenship and well-founded progress of this immediate section, this book is respectfully and lovingly dedicated. PREF.A.OE The author wishes to thus assure the readers of this work that he has made no effort to invite fame nor has he undertaken the furtherance of the art of authorship--rather it has been his in the compilation of data, facts and :figures to give the direct and diverse ramifications of the several Hamrick generations and to show the honest strivings of them as early settlers and hardy pioneers. No attempt has been made to perpetuate the fame of this great family in song and story rather the author has written, in plain and unpolished words, their rugged history. After all what could be more eloquent than the simple and hardy annals of the forebears of an honest and prosperous commonwealth whose efforts at building a sturdy citizenship have prevailed. Then too, no community is greater than the noble traditions and sentiments which it cherishes; so likewise is it with the individual. Wherefore, the writer prays the reader's leniency only as to gram matical construction for no apology is needed and none is offered for the record of achievements of the several generations herein enumerated. -

2005 Volume 11.2

GRANVILLE CONNECTIONS Journal of the Granville County Genealogical Society 1746, Inc. Volume 11, NlJIIlber 2 Spring 2005 Granville County Genealogical Society 1746, Inc. www.gcgs.org Officers for Calendar Year, 2005 President - Mildred Goss Corresponding Secretary - Velvet Satterwhite Vice President - Richard Taylor Historian - Mary McGhee Treasurer - Patricia Nelson Publication Editor -Bonnie Breedlove Recording Secretary - Shirley Pritchett Membership Membership is open to anyone with an interest in the genealogical research and preservation of materials that might aid in family research in Granville County or elsewhere. Memberships include Individual Memberships - $15.00 and Family Memberships (receiving one publication) - $20.00. Membership in the Society, with renewal due one year from joining, include copies of The Society Messenger and Granville Connections. Members are also entitled to one query per quarter to appear in Granville Connections. New members joining after November 1 may request their membership be activated for the following year, with publication commencing in that year. Editorial Policy Granville Connections places its emphasis on material concerning persons or activities in that area known as Granville County. It includes those areas of present day Vance, Warren and Franklin Counties before they became independent counties. Members are encouraged to submit material for consideration for publication. The editorial staff will judge the material on relevance to area, interest, usefulness and informative content. Members are encouraged to submit queries for each journal. Submissions must be fully documented, citing sources, or they . will not be printed. Submissions will not be returned, but will be placed in the North Carolina Room at the Richard H. Thornton library, the repository for the Society.