The Religion of Judah

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POWER MTS 251Si a Digitally-Controlled, Multi-Process MIG/TIG/Stick Welder

EVERLAST POWER MTS 251Si A Digitally-Controlled, Multi-Process MIG/TIG/Stick Welder CC CV GMAW SMAW GTAW IGBT DC PULSE Operator’s Manual for the PowerMTS 251Si Safety, Setup and General Use Guide Rev. 1 0 11114-16 everlastwelders.com Specifications and Accessories subject to change without notice. 1- 877-755-9353 329 Littlefield Ave. South San Francisco, CA 94080 USA Table of Contents Section……………………………………………….Page Letter to the Customer …………………....………… 3 Everlast Contact Information…………….…………. 4 Safety Precautions…………………………………… 5 Introduction and Specifications…..………………… 9 Overview of Parameters and Specifications……. 9 Technical Parameters……………………………... 10 General Description, Purpose and Features……. 11 Set Up Guide and Component Identification….…... 12 Suggested Settings…….…………………...…….. 12 Connections and Polarity…………………………. 14 General Polarity and Amp Recommendations…. 15 Installing The Wire Spool…………………………. 17 Front View Main Panel……………………….…… 18 Front Panel Item Description and Explanation…. 19 Side View …………………………………..…….... 26 Side View Item Description and Explanation..….. 27 Rear View Back Panel…………………………….. 28 Rear Panel Item Description and Explanation….. 29 Basic Theory and Function…………………………. 30 Basic MIG Operation…..………………………….. 30 Pulse MIG Operation……………………………… 37 Pulse MIG Work Sheets………………………….. 45 Stick Operation…………………………………….. 51 Special Notes Concerning Operation………….… 52 Basic TIG Operation………………………………. 55 TIG Arc Starting……………………………………. 57 Tungsten Preparation…………………………….. 58 Pulse TIG Operation………………………………. 59 TIG Work Sheets…………………………………... 61 25 Series MIG Torch……………………………… 64 25 Series Consumables………………………….. 65 24 Series MIG Torch……………………………… 66 24 Series Consumables………………………….. 67 26 Series TIG Torch………………………………. 68 Trouble Shooting Guide……………………………... 69 Error Codes………………………………………… 71 2 Dear Customer, THANKS! You had a choice, and you bought an Everlast product. We appreciate you as a valued customer and hope that you will enjoy years of use from your welder. -

KEEFUS CIANCIA (Discography)

KEEFUS CIANCIA 1/1/19 (Discography) Recording Album / Project Artist Credit Beyond the Palace Walls Paragon Taxi Piano, Keyboards (1993) Jazz in the Present Tense The Solsonics Keyboards (1993) Bop Gun Ice Cube Keyboards (1993) Fo Life Mack 10 Keyboards (1993) Cool Struttin The Pacific Jazz Alliance Keyboards (1994) Keyboards, Moog Synthesizer, N Gatz We Truss South Central Cartel (1994) Claves Nut-Meg Sez "Bozo the Town" Weapon of Choice Keyboards, Vocals (1994) Clavinet, Fender Rhodes, Moog Back to Reality Jeune (1995) Lead Highperspice Weapon of Choice Keyboards, Vocals (1996) I Am L.V. L.V. Keyboards (1996) Radio Odyssey Various Artists Keyboards (1996) The Jade Vincent Moy Producer, Composer, Musician (1996) Experiment Concepto Sol d'Menta Keyboards (1998) Nutmeg Phantasy Weapon of Choice Keyboards (1998) Whitey Ford Sings the Blues [Clean] Everlast Keyboards, Performer (1998) Another True Fiction Jerry Toback Moog Synthesizer (1999) Eat at Whitey's Everlast Bass, Keyboards, Band (2000) Loud Rocks Various Artists Keyboards (2000) Moog Synthesizer, Claves, You Know, for Kids Hate Fuck Trio (2000) Wurlitzer Synthesizer, Farfisa Organ, The ID Macy Gray (2001) Composer Motherland Natalie Merchant Piano, Keyboards (2001) Stimulated, Vol. 1 Various Artists Keyboards (2001) Diana Priscilla Ahn (2001) Organ, Keyboards, Clavinet, C'mon, C'mon Sheryl Crow (2002) String Samples Keyboards, Producer, Engineer, Soul of John Black The Soul of John Black (2003) Associate Producer Piano, Keyboards, Moog Thousand Kisses Deep Chris Botti (2003) Synthesizer, -

BW Unlimited Charity Fundraising

BW Unlimited Charity Fundraising www.BWUnlimited.com BW UNLIMITED IS PROUD TO PROVIDE THIS INCREDIBLE LIST OF AUTOGRAPHED SPORTS MEMORABILIA FROM AROUND THE U.S. ALL OF THESE ITEMS COME COMPLETE WITH A 3RD PARTY CERTIFICATE OF AUTHENTICITY . REMEMBER , WE NEED AT LEAST 3 WEEKS TO GET YOUR ORDER READY AND SHIPPED TO YOU PRIOR TO YOUR EVENT . WE LOOK FORWARD TO HELPING YOU . CALL US AT 443.206.6121 ~ NATIONAL AUTOGRAPHED MEMORABILIA ~ Boxing/UFC 1. 7 Former Boxing Heavyweight Champions Multi Signed Everlast White Boxing Trunks With Champion Years Inscriptions (BWUCFSCHW) $350.00 2. Adrien Broner signed Boxing Glove inscribed "The Problem" (BWUCFAD) $225.00 3. Buster Douglas & Mike Tyson dual autographed Boxing Glove (BWUCFAD) $300.00 4. Chuck Liddell UFC autographed Boxing Glove (BWUCFAD) $275.00 5. Chuck Liddell UFC autographed Iceman fighting trunks (BWUCFAD) $275.00 6. Conor McGregor autographed and framed Fighting Glove Shadowbox (BWUCFFAN) $380.00 7. Floyd Mayweather autographed Boxing Boot (BWUCFAD) $425.00 8. Floyd Mayweather autographed Yellow Boxing Trunks (BWUCFAD) $425.00 9. Floyd Mayweather Jr Signed Everlast White Boxing Robe (BWUCFSCHW) $550.00 10. Floyd Mayweather Jr. Signed Boxing Championship Green Belt (BWUCFSCHW) $550.00 11. Floyd Mayweather Jr. Signed Boxing Fighting Manny Pacquiao 16x20 Photo (BWUCFSCHW) $445.00 12. Floyd Mayweather Jr. Signed Everlast Black Boxing Glove (BWUCFSCHW) $400.00 13. George Foreman autographed Boxing Glove (BWUCFAD) $300.00 14. Jake LaMotta autographed and framed Boxing Black & White 16x20 Photo (BWUCFAD) $325.00 15. Jake LaMotta autographed Boxing Glove (BWUCFAD) $275.00 16. James Buster Douglas Signed Boxing Mike Tyson Knockout 16x20 Photo w/I Shocked The World 2-11-90 (BWUCFSCHW) $275.00 BW Unlimited, llc. -

Led Zeppelin R.E.M. Queen Feist the Cure Coldplay the Beatles The

Jay-Z and Linkin Park System of a Down Guano Apes Godsmack 30 Seconds to Mars My Chemical Romance From First to Last Disturbed Chevelle Ra Fall Out Boy Three Days Grace Sick Puppies Clawfinger 10 Years Seether Breaking Benjamin Hoobastank Lostprophets Funeral for a Friend Staind Trapt Clutch Papa Roach Sevendust Eddie Vedder Limp Bizkit Primus Gavin Rossdale Chris Cornell Soundgarden Blind Melon Linkin Park P.O.D. Thousand Foot Krutch The Afters Casting Crowns The Offspring Serj Tankian Steven Curtis Chapman Michael W. Smith Rage Against the Machine Evanescence Deftones Hawk Nelson Rebecca St. James Faith No More Skunk Anansie In Flames As I Lay Dying Bullet for My Valentine Incubus The Mars Volta Theory of a Deadman Hypocrisy Mr. Bungle The Dillinger Escape Plan Meshuggah Dark Tranquillity Opeth Red Hot Chili Peppers Ohio Players Beastie Boys Cypress Hill Dr. Dre The Haunted Bad Brains Dead Kennedys The Exploited Eminem Pearl Jam Minor Threat Snoop Dogg Makaveli Ja Rule Tool Porcupine Tree Riverside Satyricon Ulver Burzum Darkthrone Monty Python Foo Fighters Tenacious D Flight of the Conchords Amon Amarth Audioslave Raffi Dimmu Borgir Immortal Nickelback Puddle of Mudd Bloodhound Gang Emperor Gamma Ray Demons & Wizards Apocalyptica Velvet Revolver Manowar Slayer Megadeth Avantasia Metallica Paradise Lost Dream Theater Temple of the Dog Nightwish Cradle of Filth Edguy Ayreon Trans-Siberian Orchestra After Forever Edenbridge The Cramps Napalm Death Epica Kamelot Firewind At Vance Misfits Within Temptation The Gathering Danzig Sepultura Kreator -

Song List by Artist

AMAZING EMBARRASSONIC Song list by Artist CALIFORNIA LUV 2PAC AND DR.DRE DANCING QUEEN ABBA MAMA MIA ABBA S. O. S. ABBA BIG BALLS AC/DC HAVE A DRINK ON ME AC/DC HELLS BELLS AC/DC HIGHWAY TO HELL AC/DC LIVE WIRE AC/DC SIN CITY AC/DC TNT AC/DC WHOLE LOT OF ROSIE AC/DC YOU SHOOK ME ALL NIGHT LONG AC/DC CUTS LIKE A KNIFE ADAMS, BRYAN SUMMER OF '69 ADAMS, BRYAN DRAW THE LINE AEROSMITH SICK AS A DOG AEROSMITH WALK THIS WAY AEROSMITH REMEMBER( WALKING IN THE SAND) AEROSMITH BEAUTIFUL AGUILARA, CHRISTINA LOST IN LOVE AIR SUPPLY MOUNTAIN MUSIC ALABAMA ROOSTER ALICE IN CHAINS ONE WAY OUT ALLMAN BROS RAMBLIN MAN ALLMAN BROS SISTER GOLDEN HAIR AMERICA SHE'S HAVING MY BABY ANKA, PAUL SUGAR, SUGAR ARCHIES AINT SEEN NOTHING YET BACHMAN TURNER OVERDRIVE LET IT RIDE BACHMAN TURNER OVERDRIVE TAKIN CARE OF BUSINESS BACHMAN TURNER OVERDRIVE EVERYBODY BACKSTREET BOYS FEEL LIKE MAKIN' LUV BAD CO. GOOD LOVIN' GONE BAD BAD CO. SHOOTING STAR BAD CO. NO MATTER WHAT BADFINGER DO THEY KNOW IT'S X-MAS BAND-AID MANIC MONDAY BANGLES WALK LIKE AN EGYPTIAN BANGLES SATURDAY NIGHT BAY CITY ROLLERS IN MY ROOM BEACH BOYS FIGHT FOR YOUR RIGHT TO PARTY BEASTIE BOYS COME TOGETHER BEATLES DAY TRIPPER BEATLES HARD DAYS NIGHT BEATLES LET IT BE BEATLES HELTER SKELTER BEATLES HEY JUDE BEATLES SOMETHING BEATLES TWIST AND SHOUT BEATLES LOSER BECK JIVE TALKIN' BEE GEES www.amazingembarrassonic.com Page 1 9/30/15 AMAZING EMBARRASSONIC Song list by Artist MASSACHUSETTS BEE GEES STAYIN' ALIVE BEE GEES HEARTBREAKER BENATAR, PAT HELL IS FOR CHILDREN BENATAR, PAT HIT ME W/YOUR BEST SHOT -

REM E. Bow the Letter Nelly E.I Katy Perry E.T Cam Zoller Earl Didn't Die

REM E. Bow The Letter Nelly E.I Katy Perry E.T Cam Zoller Earl Didn't Die Weeknd Earned It Penguins Earth Angel UB40 Earth dies screaming Michael Jackson Earth Song Ricochet Ease My Troubled Mind Michael Jackson and Diana Ross Ease On Down The Road Jerry Reed East Bound and Down Commodores Easy Rascal Flatts & Natasha Bedingfield Easy Kiss Easy as it Seems George Strait Easy Come Easy Go Clint Black and Lisa Hartman Easy For Me To Say Terri Clark Easy From Now On Uriah Heep Easy Livin' Charlie Rich Easy Look Three Dog Night Easy To Be Hard Five For Fighting Easy Tonight Weird Al Yankovic Eat It Krokus Eat The rich Aerosmith Eat The Rich Wheeler Walker Jr Eatin Pussy/Kickin Ass Stevie Wonder & Paul McCartney Ebony And Ivory Everyly Brothers Ebony Eyes Trapt Echo Martha & The Muffins Echo Beach Pink Floyd Eclipse Sound of Music Edelweis Vince Hill Edelweiss Lady Gaga Edge of Glory Stevie Nicks Edge of Seventeen TED GÄRDESTAD Egen måne Beyonce Ego Beatles Eight Days a Week Alanis Morissette Eight Easy Steps Byrds Eight Miles High Kathy Mattea Eighteen Wheels And A Dozen Roses Marty Robbins El Paso City Amy Grant El Shaddai Sia Elastic Heart Pearl Jam Elderly woman Behind a Counter In A Small Town Low Millions Eleanor Alice Cooper Elected Eddie Grant Electric Avenue Lady Gaga Electric Chapel Marcia Griffiths Electric Slide REM Electrolite INXS Elegantly Wasted Tears for Fears Elemental Moulin Rouge Elephant Love Medley U2 Elevation Three Dog Night Eli's Coming Billy Gilman Elizabeth Bob Lind Elusive Butterfly Oak Ridge Boys Elvira Confederate -

Album Top 1000 2021

2021 2020 ARTIEST ALBUM JAAR ? 9 Arc%c Monkeys Whatever People Say I Am, That's What I'm Not 2006 ? 12 Editors An end has a start 2007 ? 5 Metallica Metallica (The Black Album) 1991 ? 4 Muse Origin of Symmetry 2001 ? 2 Nirvana Nevermind 1992 ? 7 Oasis (What's the Story) Morning Glory? 1995 ? 1 Pearl Jam Ten 1992 ? 6 Queens Of The Stone Age Songs for the Deaf 2002 ? 3 Radiohead OK Computer 1997 ? 8 Rage Against The Machine Rage Against The Machine 1993 11 10 Green Day Dookie 1995 12 17 R.E.M. Automa%c for the People 1992 13 13 Linkin' Park Hybrid Theory 2001 14 19 Pink floyd Dark side of the moon 1973 15 11 System of a Down Toxicity 2001 16 15 Red Hot Chili Peppers Californica%on 2000 17 18 Smashing Pumpkins Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness 1995 18 28 U2 The Joshua Tree 1987 19 23 Rammstein Muaer 2001 20 22 Live Throwing Copper 1995 21 27 The Black Keys El Camino 2012 22 25 Soundgarden Superunknown 1994 23 26 Guns N' Roses Appe%te for Destruc%on 1989 24 20 Muse Black Holes and Revela%ons 2006 25 46 Alanis Morisseae Jagged Liale Pill 1996 26 21 Metallica Master of Puppets 1986 27 34 The Killers Hot Fuss 2004 28 16 Foo Fighters The Colour and the Shape 1997 29 14 Alice in Chains Dirt 1992 30 42 Arc%c Monkeys AM 2014 31 29 Tool Aenima 1996 32 32 Nirvana MTV Unplugged in New York 1994 33 31 Johan Pergola 2001 34 37 Joy Division Unknown Pleasures 1979 35 36 Green Day American idiot 2005 36 58 Arcade Fire Funeral 2005 37 43 Jeff Buckley Grace 1994 38 41 Eddie Vedder Into the Wild 2007 39 54 Audioslave Audioslave 2002 40 35 The Beatles Sgt. -

Linkin Park Evanescence Vama Veche U2 Byron Coldplay

Linkin Park Evanescence Vama Veche U2 Byron Coldplay Radiohead Korn Green Day Nickelback Placebo Katy Perry Kumm Red Hot Chili Peppers My Chemical Romance Eels REM Vita de Vie Nine Inch Nails Good Charlotte Goo Goo Dolls Pennywise Barenaked Ladies Three Days Grace Alkaline Trio Alanis Morissette Guano Apes James Blunt Travka Reamonn Godsmack Fear Factory Garbage Kings Of Leon Muse Gandul Matei Sister Hazel Incubus White Zombie Papa Roach System of a Down AB4 Oasis Seether Smashing Pumpkins Alien Ant Farm The Killers Ill Nino Prodigy Taking Back Sunday Alice in Chains Kutless Timpuri Noi Taproot Snow Patrol Nonpoint Dashboard Confessional The Cure The Cranberries Stereophonics Blink 182 Phish Blur Rage Against the Machine Gorillaz Pulp Bowling For Soup Citizen Cope Manic Street Preachers Luna Amara Nirvana The Verve Breaking Benjamin Chevelle Modest Mouse Jeff Buckley Beck Arctic Monkeys Bloodhound Gang Sevendust Coma Lostprophets Keane Blue October 30 Seconds to Mars Suede Collective Soul Kill Hannah Foo Fighters The Cult Feeder Veruca Salt Skunk Anansie 3 Doors Down Deftones Sugar Ray Counting Crows Mushroomhead Electric Six Filter Lynyrd Skynyrd Biffy Clyro Death Cab For Cutie Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds The White Stripes James Morrison Texas Crazy Town Mudvayne Placebo Crash Test Dummies Poets Of The Fall Jason Mraz Linkin Park Sum 41 Grimus Guster A Perfect Circle Tool The Strokes Flyleaf Chris Cornell Smile Empty Soul Audioslave Nirvana Gogol Bordello Bloc Party Thousand Foot Krutch Brand New Razorlight Puddle Of Mudd Sonic Youth -

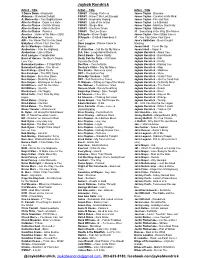

Got Me Wrong

Jaykob Kendrick Artist - Title Artist - Title Artist - Title 3 Doors Down - Kryptonite CSN&Y - Change Partners James Taylor - Blossom Alabama – Dixieland Delight CSN&Y - Haven't We Lost Enough James Taylor - Carolina in My Mind A. Morissette – You Oughta Know CSN&Y - Helplessly Hoping James Taylor - Fire and Rain Alice in Chains - Down in a Hole CSN&Y - Lady of the Island James Taylor - Lo & Behold Alice in Chains - Got Me Wrong CSN&Y - Simple Man James Taylor - Machine Gun Kelly Alice in Chains - Man in the Box CSN&Y - Southern Cross James Taylor - Millworker Alice in Chains - Rooster CSN&Y - The Lee Shore JT - Something in the Way She Moves America – Horse w/ No Name ($20) D’Angelo – Brown Sugar James Taylor - Sweet Baby James Amy Winehouse – Valerie D’Angelo – Untitled (How does it JT - You Can Close Your Eyes AW – You Know That I’m No Good feel?) Jane's Addiction - Been Caught Babyface - When Can I See You Dave Loggins - Please Come to Stealing Arctic Monkeys - Arabella Boston Jason Isbell – Cover Me Up Audioslave - I Am the Highway D. Allan Coe - Call Me By My Name Jason Isbell – Super 8 Audioslave - Like a Stone D.A. Coe - Long-Haired Redneck Jaykob Kendrick - About You Avril Lavigne - Complicated David Bowie - Space Oddity Jaykob Kendrick - Barrelhouse Band of Horses - No One's Gonna Death Cab for Cutie – I’ll Follow Jaykob Kendrick - Fall Love You You into the Dark Jaykob Kendrick - Firefly Barenaked Ladies – If I had $1M Des’Ree – You Gotta Be Jaykob Kendrick - Kissing You Barenaked Ladies - One Week Destiny’s Child – Say My Name Jaykob Kendrick - Map Ben E King – Stand By Me Dire Straits - Romeo & Juliet Jaykob Kendrick - Medicine Ben Erickson - The BBQ Song DBT – Decoration Day Jaykob Kendrick - Muse Ben Harper - Burn One Down Drive-By Truckers - Outfit Jaykob Kendrick - Nuckin' Futs Ben Harper - Steal My Kisses DBT - Self-Destructive Zones Jaykob Kendrick – On the Good Foot Ben Harper - Waiting on an Angel D. -

AC/DC BONFIRE 01 Jailbreak 02 It's a Long Way to the Top 03 She's Got

AC/DC AEROSMITH BONFIRE PANDORA’S BOX DISC II 01 Toys in the Attic 01 Jailbreak 02 Round and Round 02 It’s a Long Way to the Top 03 Krawhitham 03 She’s Got the Jack 04 You See Me Crying 04 Live Wire 05 Sweet Emotion 05 T.N.T. 06 No More No More 07 Walk This Way 06 Let There Be Rock 08 I Wanna Know Why 07 Problem Child 09 Big 10” Record 08 Rocker 10 Rats in the Cellar 09 Whole Lotta Rosie 11 Last Child 10 What’s Next to the Moon? 12 All Your Love 13 Soul Saver 11 Highway to Hell 14 Nobody’s Fault 12 Girls Got Rhythm 15 Lick and a Promise 13 Walk All Over You 16 Adam’s Apple 14 Shot Down in Flames 17 Draw the Line 15 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap 18 Critical Mass 16 Ride On AEROSMITH PANDORA’S BOX DISC III AC/DC 01 Kings and Queens BACK IN BLACK 02 Milk Cow Blues 01 Hells Bells 03 I Live in Connecticut 02 Shoot to Thrill 04 Three Mile Smile 05 Let It Slide 03 What Do You Do For Money Honey? 06 Cheesecake 04 Given the Dog a Bone 07 Bone to Bone (Coney Island White Fish) 05 Let Me Put My Love Into You 08 No Surprize 06 Back in Black 09 Come Together 07 You Shook Me All Night Long 10 Downtown Charlie 11 Sharpshooter 08 Have a Drink On Me 12 Shithouse Shuffle 09 Shake a Leg 13 South Station Blues 10 Rock and Roll Ain’t Noise Pollution 14 Riff and Roll 15 Jailbait AEROSMITH 16 Major Barbara 17 Chip Away the Stone PANDORA’S BOX DISC I 18 Helter Skelter 01 When I Needed You 19 Back in the Saddle 02 Make It 03 Movin’ Out AEROSMITH 04 One Way Street PANDORA’S BOX BONUS CD 05 On the Road Again 01 Woman of the World 06 Mama Kin 02 Lord of the Thighs 07 Same Old Song and Dance 03 Sick As a Dog 08 Train ‘Kept a Rollin’ 04 Big Ten Inch 09 Seasons of Wither 05 Kings and Queens 10 Write Me a Letter 06 Remember (Walking in the Sand) 11 Dream On 07 Lightning Strikes 12 Pandora’s Box 08 Let the Music Do the Talking 13 Rattlesnake Shake 09 My Face Your Face 14 Walkin’ the Dog 10 Sheila 15 Lord of the Thighs 11 St. -

Hip-Hop Realness and the White Performer Mickey Hess

Critical Studies in Media Communication Vol. 22, No. 5, December 2005, pp. 372Á/389 Hip-hop Realness and the White Performer Mickey Hess Hip-hop’s imperatives of authenticity are tied to its representations of African-American identity, and white rap artists negotiate their place within hip-hop culture by responding to this African-American model of the authentic. This article examines the strategies used by white artists such as Vanilla Ice, Eminem, and the Beastie Boys to establish their hip- hop legitimacy and to confront rap music’s representations of whites as socially privileged and therefore not credible within a music form where credibility is often negotiated through an artist’s experiences of social struggle. The authenticating strategies of white artists involve cultural immersion, imitation, and inversion of the rags-to-riches success stories of black rap stars. Keywords: Hip-hop; Rap; Whiteness; Racial Identity; Authenticity; Eminem Although hip-hop music has become a global force, fans and artists continue to frame hip-hop as part of African-American culture. In his discussion of Canadian, Dutch, and French rap Adam Krims (2000) noted the prevailing image of African-American hip-hop as ‘‘real’’ hip-hop.1 African-American artists often extend this image of the authentic to frame hip-hop as a black expressive culture facing appropriation by a white-controlled record industry. This concept of whiteÁ/black interaction has led white artists either to imitate the rags-to-riches narratives of black artists, as Vanilla Ice did in the fabricated biography he released to the press in 1990, or to invert these narratives, as Eminem does to frame his whiteness as part of his struggle to succeed as a hip-hop artist. -

Introduction Globalization Era Give Both Positive and Negative Effects To

“MORAL VALUES AND FIGURATIVE LANGUAGES IN COLDPLAY’S BAND” Ripki Pratama, Muhammad Fadjri English Department, Faculty of Teacher Training and Education, Mataram University [email protected] ABSTRACT This thesis entitled “Moral Values And Figurative Languages in Coldplay’s Band Songs. Formalis theory and Affective theory are used in analyzing the moral values and figurative languages. Theory that used to image moral values is Formalist theory and theory that used to analysis figurative is Affective thoery. Then, data analyzed by using descriptive analysis method. The result of this study is there are several moral values that found in coldplays song such as regiousity, love, humbleness, peace loving. Figurative languages found are methapor, similie, personification, irony, and symbol in lyrics. Key words: Moral Value, Figurative language, Formalist theory, Affective theory, Descriptive Analysis Method. Introduction Globalization era give both positive and negative effects to many aspect of human life. It make such great development in techonology, science, medical and arts. The development in arts musician can easily spread and sell their album or songs through internet in digital form. Music is one of the entertainment which people love beacuse everybody have heard music and they may like music and even have musician idol. Music also tell about story which can be influence the listener’s mood and feeling. Many people may not run their day without music beacuse music can be ways to accompany while they work, study, exercise which make more relaxed. Music can represent the feeling of the singer which can be bad feeling and good feeling. It all will be represent through the lyrics.