A Panel Discussion On: “New Hope for New Orleans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Foundation for a Beautiful Life, Inc., ) No

USCA Case #20-1159 Document #1845273 Filed: 06/02/2020 Page 1 of 22 IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT ) In re: Foundation for a Beautiful Life, Inc., ) No. 20-1159 Petitioner. ) ) OPPOSITION OF FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION TO EMERGENCY MOTION FOR STAY PENDING REVIEW The Court should deny the motion for stay filed by Foundation for a Beautiful Life, Inc. (FBL). FBL has no right to operate a radio station in northern California because it has never obtained a license from the Federal Communications Commission to do so. The FCC issued a permit for FBL to construct a low-power FM radio station in Cupertino, California. But FBL inexplicably built its station in Saratoga, California, several miles away. FBL’s Cupertino construction permit expired in 2018, and its related application for a broadcast license was dismissed in 2019. On March 20, 2020, FBL asked the Commission for Special Temporary Authority (STA) to operate its station to provide information on Covid-19 to the Mandarin-speaking community of Cupertino. Without waiting for Commission action on its request (which had not properly been submitted), FBL began broadcasting on March 27, 2020. By letter dated April 16, 2020, the Commission’s Media Bureau dismissed FBL’s STA request as procedurally USCA Case #20-1159 Document #1845273 Filed: 06/02/2020 Page 2 of 22 2 defective and, in the alternative, denied the request on the merits. The Bureau also ordered FBL to cease operating the station immediately. Invoking the All Writs Act, 28 U.S.C. -

Great Law Firms Choose Each Other. Resolution Specialists

Great Clients Choose Great Law Firms; Great Law Firms Choose Each Other. Upchurch Watson White and Max specializes in settling disputes - anywhere. For over 20 years, the principals and panelists at our firm, have successfully guided clients and attorneys through the field of conflict resolution. Our experienced mediators will help you and your clients find the road to common ground. RCH WA HU TSO PC N U Resolution Specialists W X HITE & MA uww-adr.com Daytona Beach, FL • Maitland / Orlando, FL • Miami, FL • Birmingham, AL the Briefs May 2011 Vol. 79 No. 5 www.orangecountybar.org PAGE 1 the Brie s Contents f©2011 Co-Editors 3 Vivian P. Cocotas & Sarah P. L. Reiner President’s Message 16 YLS on the Move Associate Editors One Last Message! Allison C. McMillen & Suzanne D. Meehle Jacquelynne J. Regan Frank M. Bedell 23 Side Bar Columnist 4 Sunny Lim Hillary The Basics: Marketing Your Law Professionalism Committee Firm Online YLS Columnist Remarks by The Honorable John FindLaw Jacquelynne J. Regan Marshall Kest upon Receiving the 2011 w James G. Glazebrook Memorial Bar 24 Service Award OFFICERS What Do You Mean I Wasn’t Frank M. Bedell, President Picked for the Jury? 8 Thomas A. Zehnder, President-Elect Jamie Billotte Moses Hints: Professionalism Questions to Ask Kristyne E. Kennedy, Treasurer Yourself Before You React 26 Paul J. Scheck, Secretary SideBar The Honorable John Marshall Kest w Sunny L. Hillary 10 EXECUTIVE COUNCIL Wiley S. Boston What Great Writers Can Teach Lawyers 28 Rainmaking and Judges: Wisdom from Plato to Mark Mary Ann Etzler Twain to Stephen King Market Yourself through Storytelling Meenakshi A. -

Letter Was Presented to the Commissioner Signed by the Ceos of 50 Minority Owned AM Radio Licensees, Collectively Owning 140 AM Stations.'

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BLACK OWNED BROADCASTERS 1201 Connecticut Avenue, N .W., Sui te 200, W ashington, D.C 20036 (202) 463-8970 • Fax: (2 02) 429-0657 September 2, 2015 BOARD OF DIRECTORS JAMES L. WINSlOI\ President Marlene H. Dortch, Secretary MICHAEL L. CARTER Vice President Federal Communications Commission KAREN E. SLADE 445 12th Street NW Treasurer C. LOIS E. WRIGHT Washington, D. 20554 Counsel 10 the 80ii1td ARTHUR BEN JAMI Re: Notice of Ex Parte Communication, MB Docket 13- CAROL MOORE CUTTING 249, Revitalization of the AM Radio Service ALFRED G. LIGGINS ("Notice") JE RRY LOPES DUJUAN MCCOY STEVEN ROBERTS Review of the Emergency Alert System (EB Docket MELODY SPANN-COOPER No. 04-296); Recommendations of the Independent JAMES E. WOL FE, JR. Panel Reviewing the Impact of Hurricane Katrina on Communications Networks (EB Docket 06-119) Dear Ms. Dortch: On September 1, 2015, the undersigned President of the National Association of Black Owned Broadcasters, Inc. ("NABOB") along with Francisco Montero of Fletcher, Heald & Hildreth, PLC, and David Honig, President Emeritus and Senior Advisor, Multicultural Media, Telecommunications and Internet Council ("MMTC") met with Commissioner Ajit Pai and Alison Nemeth, Legal Advisor, to discuss the most important and effective proposal set forth in the AM Revitalization Notice: opening an application filing window for FM translators that would be limited to AM broadcast licensees. As the Commission recognized in the Notice, the best way to help the largest number of AM stations to quickly and efficiently improve their service is to open such an AM-only window. Any other approach will make it extremely difficult, if not impossible, for AM stations, to obtain the translators they urgently need to remain competitive and provide our communities with the service they deserve. -

Maine Campus April 25 1929 Maine Campus Staff

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Maine Campus Archives University of Maine Publications Spring 4-25-1929 Maine Campus April 25 1929 Maine Campus Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainecampus Repository Citation Staff, Maine Campus, "Maine Campus April 25 1929" (1929). Maine Campus Archives. 3418. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainecampus/3418 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine Campus Archives by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Vie ttlaine Campo'.etseviewr 'it 16, Presi- Published Weekly by the Students of the University of Maine graciously innual recep- Vol. XXX ORONO, MAINE, nor class re- APRIL 25, 1929 No. 25 Niwding the to 9. !feat' mica Buzz.:II lau Epsilon Phi eceising line. Maine in and Mrs. Men Leave For Penn Relays Today Kent Elected President Fielder, and Grants Charter for Sandwiches, were sersed Of Student Senate: Seniors isgatt, Dora Maine Chapter rma Buddeti • Ittliohi for a chapter 1.i Tau 1:p .ase and Mrs. natiomil Hebrew irxernity. Nominated for Alumni Watch 1.41. all in all ! hy I lehrew students at the l'niser- ic h,ospital • „/ main,has been pi:ISM:11 1),\ the n4- Iman is deep- chapter of the fratnrnity. it ha'. Daley Elected New Vice President and Crockett ,1, ruth from ge.,.el authority. The Omicron Pi 'ri tudents at M:iint• hate bee., Secretary-Treasurer: Names of Twenty patronesses. •I t..gether in the s,wiety called the Placed On List of Nominations Nino. -

Licensing and Management System

Approved by OMB (Office of Management and Budget) 3060-0010 September 2019 (REFERENCE COPY - Not for submission) Commercial Broadcast Stations Biennial Ownership Report (FCC Form 323) File Number: 0000103960 Submit Date: 2020-01-31 FRN: 0010215812 Purpose: Commercial Broadcast Stations Biennial Ownership Report Status: Received Status Date: 01/31/2020 Filing Status: Active Section I - General Information 1. Respondent FRN Entity Name 0005086368 Multicultural Radio Broadcasting, Inc. Street City (and Country if non U.S. State ("NA" if non-U.S. Zip Address address) address) Code Phone Email 40 New York NY 10005 +1 (212) 431- seank@mrbi. Exchange 4300 net Place Suite 1010 2. Contact Name Organization Representative Mark N. Lipp Fletcher Heald & Hildreth, P.L.C. Street Address City (and Country if non U.S. address) State Zip Code Phone Email 1300 North Arlington VA 22209 +1 (703) 812-0445 [email protected] 17th Street 11th Floor Not Applicable 3. Application Filing Fee 4. Nature of (a) Provide the following information about the Respondent: Respondent Relationship to stations/permits Entity required to file a Form 323 because it holds an attributable interest in one or more Licensees Nature of Respondent For-profit corporation (b) Provide the following information about this report: Purpose Biennial "As of" date 10/01/2019 When filing a biennial ownership report or validating and resubmitting a prior biennial ownership report, this date must be Oct. 1 of the year in which this report is filed. 5. Licensee(s) Respondent is filing this report to cover the following Licensee(s) and station(s): and Station(s) Licensee/Permittee Name FRN Multicultural Radio Broadcasting Licensee, LLC 0010215812 Fac. -

Association of Educational Therapists, Inc. Last Updated 7044 S

Page 1 Association of Educational Therapists, Inc. Last Updated 7044 S. 13th St. 09/27/2021 02:30:03 Oak Creek, WI 53154 (414) 908-4949 Membership Directory To search within this pdf press (COMMAND-F) or (Ctrl+ F) depending upon your operating system. Australia ALLIED Brumfitt, Anne Telephone 400036240 Email [email protected] FAX Australia ASSOCIATE Wilson, Kerri MSpEd,BEd,BTeach LRW Pre-School Elementary Learning Ladders Australia PP 3 The Grove Telephone 0415837718 EdC Email [email protected] Thornlands Australia FAX Canada AB ASSOCIATE Ewen, Shauna M.Ed. +30, B.Ed LRW TEST ESL Adolescent Pre-School Adult Elementary Literacy For Life Reading Clinic, Inc. PP 304 Windermere Road Telephone +1 587 858 5700 PS Email [email protected] EdC Edmonton AB T6W 2P2 Canada FAX Canada BC ASSOCIATE Crescenzo, Tina M.Ed. LRW STSK ADV Adolescent Elementary Cobblestone Educational Therapy 2147 Knightswood Place Telephone 604-562-6202 Email [email protected] Burnaby BC V5A4B9 Canada FAX Last Updated 09/27/2021 02:30:05 Page 2 Association of Educational Therapists, Inc. Last Updated 7044 S. 13th St. 09/27/2021 02:30:05 Oak Creek, WI 53154 (414) 908-4949 Membership Directory To search within this pdf press (COMMAND-F) or (Ctrl+ F) depending upon your operating system. Canada ON ASSOCIATE Bajurny, Claire LRW STSK MATH ESL Adolescent Adult Elementary Telephone 6476172174 Email [email protected] The Hague 2555ME Netherlands FAX Leeder, Sheri B.A., B.Ed., M.Ed. LRW MATH TEST Adolescent Pre-School Elementary Ability Therapy Services RSP 50 Bournemouth Ave Telephone 519-404-9735 EdC Email [email protected] PP Kitchener ON N2B 1M7 Canada FAX France PROFESSIONAL Adibi, Denielle Education, M.A. -

It's Written in Our Head: the Possibilities and Contradictions of a Feminist Poststructuralist Discourse in a Junior Primary Classroom

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 383 023 CS 508 933 AUTHOR O'Brien, Jennifer TITLE It's Written in Our Head: The Possibilities and Contradictions of a Feminist Poststructuralist Discourse in a Junior Primary Classroom. PUB DATE Jul 94 NOTE 154p.; Master of Education Thesis, University of South Australia. PUB TYPE' Reports Evaluative/Feasibility (142) Dissertations /Theses Masters Theses (042) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Classroom Communication; Classroom Environment; Communication Research; Discourse Analysis; *Feminism; Foreign Countries; Primary Education; Reading Aloud to Others; *Reading Instruction; *Sex Differences; *Teacher Student Relationship IDENTIFIERS Australia; *Communication Behavior; Critical Pedagogy; Discourse Communities; *Poststructuralism ABSTRACT A study examined from a feminist poststructuralist perspective the discourses available in a classroom using a critical pedagogy, based on a belief that teaches need to make it possible for their students to question the social world constructed in texts. The teacher of an Australian junior primary classroom (with students age five to eight) took as her starting point a critically-based literature advocating the introduction of a critical discourse into classrooms. The teacher also took into account the impact of poststructuralist prediction of multiplicity, contradiction and possibility on research and pedagogical positions. To scrutinize the discursive practices around this critical pedagogy, the teacher/researcher made multiple readings around two fiction texts, revealing both the contradictory discourses and the possibilities available in a classroom where a critical pedagogy with a Feminist poststructuralist emphasis underpinn'd reading instruction. Results indicated that:(1) the critical discourse the teacher made available was taken up differentially by girls and by boys;(2) students' existing practices associated with old positions concerning the meaning in the texts were preserved; and (3) some girls did take up new, socially-critical positions. -

530 CIAO BRAMPTON on ETHNIC AM 530 N43 35 20 W079 52 54 09-Feb

frequency callsign city format identification slogan latitude longitude last change in listing kHz d m s d m s (yy-mmm) 530 CIAO BRAMPTON ON ETHNIC AM 530 N43 35 20 W079 52 54 09-Feb 540 CBKO COAL HARBOUR BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N50 36 4 W127 34 23 09-May 540 CBXQ # UCLUELET BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 56 44 W125 33 7 16-Oct 540 CBYW WELLS BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N53 6 25 W121 32 46 09-May 540 CBT GRAND FALLS NL VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 57 3 W055 37 34 00-Jul 540 CBMM # SENNETERRE QC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 22 42 W077 13 28 18-Feb 540 CBK REGINA SK VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N51 40 48 W105 26 49 00-Jul 540 WASG DAPHNE AL BLK GSPL/RELIGION N30 44 44 W088 5 40 17-Sep 540 KRXA CARMEL VALLEY CA SPANISH RELIGION EL SEMBRADOR RADIO N36 39 36 W121 32 29 14-Aug 540 KVIP REDDING CA RELIGION SRN VERY INSPIRING N40 37 25 W122 16 49 09-Dec 540 WFLF PINE HILLS FL TALK FOX NEWSRADIO 93.1 N28 22 52 W081 47 31 18-Oct 540 WDAK COLUMBUS GA NEWS/TALK FOX NEWSRADIO 540 N32 25 58 W084 57 2 13-Dec 540 KWMT FORT DODGE IA C&W FOX TRUE COUNTRY N42 29 45 W094 12 27 13-Dec 540 KMLB MONROE LA NEWS/TALK/SPORTS ABC NEWSTALK 105.7&540 N32 32 36 W092 10 45 19-Jan 540 WGOP POCOMOKE CITY MD EZL/OLDIES N38 3 11 W075 34 11 18-Oct 540 WXYG SAUK RAPIDS MN CLASSIC ROCK THE GOAT N45 36 18 W094 8 21 17-May 540 KNMX LAS VEGAS NM SPANISH VARIETY NBC K NEW MEXICO N35 34 25 W105 10 17 13-Nov 540 WBWD ISLIP NY SOUTH ASIAN BOLLY 540 N40 45 4 W073 12 52 18-Dec 540 WRGC SYLVA NC VARIETY NBC THE RIVER N35 23 35 W083 11 38 18-Jun 540 WETC # WENDELL-ZEBULON NC RELIGION EWTN DEVINE MERCY R. -

Black's Law Dictionary®

BLACK'S LAW DICTIONARY® Definitions of the Terms and Phrases of American and English Jurisprudence, Ancient and Modern By HENRY CAMPBELL BLACK, M. A. SIXTH EDITION BY THE PUBLISHER'S EDITORIAL STAFF Coauthors JOSEPH R. NOLAN Associate Justice, Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court and JACQUELINE M. NOLAN-HALEY Associate Clinical Professor, Fordham University School of Law Contributing Authors M. J. CONNOllY Associate Professor (Linguistics), College of Arts & Sciences, Boston College STEPHEN C. HICKS Professor of Law, Suffolk University Law School, Boston, MA MARTINA N. All BRANDI Certified Public Accountant, Bolton, MA ST. PAUL, MINN. WEST PUBLISHING CO. 1990 "BLACK'S LAW DICTIONARY" is a registered trademark of West Publishing Co. Registered in U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. COPYRIGHT @ 1891, 1910, 1933, 1951, 1957, 1968, 1979 WEST PUBLISHING CO. COPYRIGHT @ 1990 By WEST PUBLISHING CO. 50 West Kellogg Boulevard P.O. Box 64526 St. Paul, Mn 55164-0526 All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Black, Henry Campbell, 1850-1927. [Law dictionary] Black's law dictionary / by Henry Campbell Black. - 6th ed. / by the publisher's editorial staff; contributing authors, Joseph R. Nolan ... let al.] p. cm. ISBN 0-314-76271-X 1. Law-United States-Dictionaries. 2. Law-Dictionaries. I. Nolan, Joseph R. II. Title. KF156.B53 1990 340' .03-dc20 90-36225 CIP ISBN 0-314-76271-X ISBN 0-314-77165-4 deluxe Black's Law Dictionary 6th Ed. 2nd Reprint-1990 PREFACE This new Sixth Edition starts a second century for Black's Law Dictionary-the standard authority for legal definitions since 1891. -

Will Asian Women Call a Telephone Health Information Service?

S. Davis / Californian Journal of Health Promotion 2003, Volume 1, Issue 1, 103-108 Will Asian Women Call a Telephone Health Information Service? Sharon Watkins Davis Northern California Cancer Center Abstract AAPI women have the lowest breast cancer screening rates of all U.S. women. Barriers to screening include access, culture, and language. Previous focus group studies have shown little use of telephone hotlines among Asians. However, this report indicates that media promotions in Cantonese, Mandarin, Vietnamese, and Korean can result in a major increase in calls to a California statewide telephone service. Calls from women speaking Asian languages to the California Breast Cancer Early Detection Program Consumer 800 Number increased from an average of 24 per month to 576 in June 2001 in response to paid newspaper and radio advertisements in Los Angeles, San Diego, and the San Francisco Bay Area. © 2003 Californian Journal of Health Promotion. All rights reserved. Keywords: Asian women, cancer, primary prevention, early detection Background and Significance cultural belief that if nothing is wrong, no tests Breast cancer incidence and mortality rates are should be done. Cost and insurance barriers lower for Asian American and Pacific Islander were also shown to be major concerns (Lee, (AAPI) women than for Whites or Blacks in the 1998). United States (American Cancer Society, 2001). However, invasive breast cancer rates increased AAPI women seek health information from by about 15 percent among AAPI women in health professionals, including traditional California from 1998 – 1997, compared with medicine practitioners such as herbalists, family fairly stable rates for other ethnic groups members, and the media. -

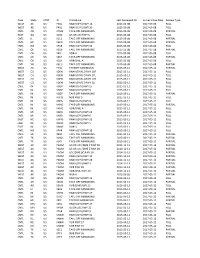

Area State CTRY ID Procedure Last Reviewed on Current Due Date Review Type WEST AK US PAVL RNAV (GPS) RWY 12 2015-05-08 2017-05

Area State CTRY ID Procedure Last Reviewed On Current Due Date Review Type WEST AK US PAVL RNAV (GPS) RWY 12 2015-05-08 2017-05-08 FULL WEST AK US PAVL RNAV (GPS) RWY 30 2015-05-08 2017-05-08 FULL CNTL AR US K7M4 TAKE-OFF MINIMUMS 2015-05-08 2017-05-08 PARTIAL EAST GA US KCSG ILS OR LOC RWY 6 2015-05-08 2017-05-08 FULL CNTL IL US K1C1 TAKE-OFF MINIMUMS 2015-05-08 2017-05-08 PARTIAL CNTL MI US K6G0 TAKE-OFF MINIMUMS 2015-05-08 2017-05-08 PARTIAL CNTL ND US KFAR RNAV (GPS) RWY 36 2015-05-08 2017-05-08 FULL CNTL OH US K3G6 TAKE-OFF MINIMUMS 2015-05-08 2017-05-08 PARTIAL CNTL OH US K4I9 VOR-A 2015-05-08 2017-05-08 FULL CNTL OK US K6K4 TAKE-OFF MINIMUMS 2015-05-08 2017-05-08 PARTIAL CNTL OK US KCLK VOR/DME-A 2015-05-08 2017-05-08 FULL CNTL WI US K3CU TAKE-OFF MINIMUMS 2015-05-08 2017-05-08 PARTIAL WEST AK US PAVL TAKEOFF MINIMUMS 2015-05-11 2017-05-11 PARTIAL WEST CO US KDEN RNAV (RNP) Z RWY 16R 2015-05-11 2017-05-11 FULL WEST CO US KDEN RNAV (RNP) Z RWY 17L 2015-05-11 2017-05-11 FULL WEST CO US KDEN RNAV (RNP) Z RWY 17R 2015-05-11 2017-05-11 FULL WEST CO US KDEN RNAV (RNP) Z RWY 26 2015-05-11 2017-05-11 FULL CNTL IN US KGGP RNAV (GPS) RWY 27 2015-05-11 2017-05-11 FULL CNTL IN US KGGP RNAV (GPS) RWY 9 2015-05-11 2017-05-11 FULL CNTL IN US KGGP TAKE-OFF MINIMUMS 2015-05-11 2017-05-11 PARTIAL CNTL IN US KHHG NDB RWY 9 2015-05-11 2017-05-11 FULL CNTL IN US KHHG RNAV (GPS) RWY 9 2015-05-11 2017-05-11 FULL CNTL IN US KHHG TAKE-OFF MINIMUMS 2015-05-11 2017-05-11 PARTIAL CNTL IN US KHHG VOR/DME-A 2015-05-11 2017-05-11 FULL CNTL MI US KARB RNAV (GPS) -

Hearst Corporation Los Angeles Examiner Photographs, Negatives and Clippings--Portrait Files (G-M) 7000.1B

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c80v8b5j No online items Hearst Corporation Los Angeles Examiner photographs, negatives and clippings--portrait files (G-M) 7000.1b Finding aid prepared by Rebecca Hirsch. Data entry done by Nick Hazelton, Rachel Jordan, Siria Meza, Megan Sallabedra, Sarah Schreiber, Brian Whitaker and Vivian Yan The processing of this collection and the creation of this finding aid was funded by the generous support of the Council on Library and Information Resources. USC Libraries Special Collections Doheny Memorial Library 206 3550 Trousdale Parkway Los Angeles, California, 90089-0189 213-740-5900 [email protected] 2012 April 7000.1b 1 Title: Hearst Corporation Los Angeles Examiner photographs, negatives and clippings--portrait files (G-M) Collection number: 7000.1b Contributing Institution: USC Libraries Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 833.75 linear ft.1997 boxes Date (bulk): Bulk, 1930-1959 Date (inclusive): 1903-1961 Abstract: This finding aid is for letters G-M of portrait files of the Los Angeles Examiner photograph morgue. The finding aid for letters A-F is available at http://www.usc.edu/libraries/finding_aids/records/finding_aid.php?fa=7000.1a . The finding aid for letters N-Z is available at http://www.usc.edu/libraries/finding_aids/records/finding_aid.php?fa=7000.1c . creator: Hearst Corporation. Arrangement The photographic morgue of the Hearst newspaper the Los Angeles Examiner consists of the photographic print and negative files maintained by the newspaper from its inception in 1903 until its closing in 1962. It contains approximately 1.4 million prints and negatives. The collection is divided into multiple parts: 7000.1--Portrait files; 7000.2--Subject files; 7000.3--Oversize prints; 7000.4--Negatives.