Life Expectation in Organic Brain Disease David Jolley & David Baxter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Episode Psychosis an Information Guide Revised Edition

First episode psychosis An information guide revised edition Sarah Bromley, OT Reg (Ont) Monica Choi, MD, FRCPC Sabiha Faruqui, MSc (OT) i First episode psychosis An information guide Sarah Bromley, OT Reg (Ont) Monica Choi, MD, FRCPC Sabiha Faruqui, MSc (OT) A Pan American Health Organization / World Health Organization Collaborating Centre ii Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Bromley, Sarah, 1969-, author First episode psychosis : an information guide : a guide for people with psychosis and their families / Sarah Bromley, OT Reg (Ont), Monica Choi, MD, Sabiha Faruqui, MSc (OT). -- Revised edition. Revised edition of: First episode psychosis / Donna Czuchta, Kathryn Ryan. 1999. Includes bibliographical references. Issued in print and electronic formats. ISBN 978-1-77052-595-5 (PRINT).--ISBN 978-1-77052-596-2 (PDF).-- ISBN 978-1-77052-597-9 (HTML).--ISBN 978-1-77052-598-6 (ePUB).-- ISBN 978-1-77114-224-3 (Kindle) 1. Psychoses--Popular works. I. Choi, Monica Arrina, 1978-, author II. Faruqui, Sabiha, 1983-, author III. Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, issuing body IV. Title. RC512.B76 2015 616.89 C2015-901241-4 C2015-901242-2 Printed in Canada Copyright © 1999, 2007, 2015 Centre for Addiction and Mental Health No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without written permission from the publisher—except for a brief quotation (not to exceed 200 words) in a review or professional work. This publication may be available in other formats. For information about alterna- tive formats or other CAMH publications, or to place an order, please contact Sales and Distribution: Toll-free: 1 800 661-1111 Toronto: 416 595-6059 E-mail: [email protected] Online store: http://store.camh.ca Website: www.camh.ca Disponible en français sous le titre : Le premier épisode psychotique : Guide pour les personnes atteintes de psychose et leur famille This guide was produced by CAMH Publications. -

Resource Document on Social Determinants of Health

APA Resource Document Resource Document on Social Determinants of Health Approved by the Joint Reference Committee, June 2020 "The findings, opinions, and conclusions of this report do not necessarily represent the views of the officers, trustees, or all members of the American Psychiatric Association. Views expressed are those of the authors." —APA Operations Manual. Prepared by Ole Thienhaus, MD, MBA (Chair), Laura Halpin, MD, PhD, Kunmi Sobowale, MD, Robert Trestman, PhD, MD Preamble: The relevance of social and structural factors (see Appendix 1) to health, quality of life, and life expectancy has been amply documented and extends to mental health. Pertinent variables include the following (Compton & Shim, 2015): • Discrimination, racism, and social exclusion • Adverse early life experiences • Poor education • Unemployment, underemployment, and job insecurity • Income inequality • Poverty • Neighborhood deprivation • Food insecurity • Poor housing quality and housing instability • Poor access to mental health care All of these variables impede access to care, which is critical to individual health, and the attainment of social equity. These are essential to the pursuit of happiness, described in this country’s founding document as an “inalienable right.” It is from this that our profession derives its duty to address the social determinants of health. A. Overview: Why Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) Matter in Mental Health Social determinants of health describe “the causes of the causes” of poor health: the conditions in which individuals are “born, grow, live, work, and age” that contribute to the development of both physical and psychiatric pathology over the course of one’s life (Sederer, 2016). The World Health Organization defines mental health as “a state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community” (World Health Organization, 2014). -

Spanish Clinical Language and Resource Guide

SPANISH CLINICAL LANGUAGE AND RESOURCE GUIDE The Spanish Clinical Language and Resource Guide has been created to enhance public access to information about mental health services and other human service resources available to Spanish-speaking residents of Hennepin County and the Twin Cities metro area. While every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of the information, we make no guarantees. The inclusion of an organization or service does not imply an endorsement of the organization or service, nor does exclusion imply disapproval. Under no circumstances shall Washburn Center for Children or its employees be liable for any direct, indirect, incidental, special, punitive, or consequential damages which may result in any way from your use of the information included in the Spanish Clinical Language and Resource Guide. Acknowledgements February 2015 In 2012, Washburn Center for Children, Kente Circle, and Centro collaborated on a grant proposal to obtain funding from the Hennepin County Children’s Mental Health Collaborative to help the agencies improve cultural competence in services to various client populations, including Spanish-speaking families. These funds allowed Washburn Center’s existing Spanish-speaking Provider Group to build connections with over 60 bilingual, culturally responsive mental health providers from numerous Twin Cities mental health agencies and private practices. This expanded group, called the Hennepin County Spanish-speaking Provider Consortium, meets six times a year for population-specific trainings, clinical and language peer consultation, and resource sharing. Under the grant, Washburn Center’s Spanish-speaking Provider Group agreed to compile a clinical language guide, meant to capture and expand on our group’s “¿Cómo se dice…?” conversations. -

Eating Disorders: About More Than Food

Eating Disorders: About More Than Food Has your urge to eat less or more food spiraled out of control? Are you overly concerned about your outward appearance? If so, you may have an eating disorder. National Institute of Mental Health What are eating disorders? Eating disorders are serious medical illnesses marked by severe disturbances to a person’s eating behaviors. Obsessions with food, body weight, and shape may be signs of an eating disorder. These disorders can affect a person’s physical and mental health; in some cases, they can be life-threatening. But eating disorders can be treated. Learning more about them can help you spot the warning signs and seek treatment early. Remember: Eating disorders are not a lifestyle choice. They are biologically-influenced medical illnesses. Who is at risk for eating disorders? Eating disorders can affect people of all ages, racial/ethnic backgrounds, body weights, and genders. Although eating disorders often appear during the teen years or young adulthood, they may also develop during childhood or later in life (40 years and older). Remember: People with eating disorders may appear healthy, yet be extremely ill. The exact cause of eating disorders is not fully understood, but research suggests a combination of genetic, biological, behavioral, psychological, and social factors can raise a person’s risk. What are the common types of eating disorders? Common eating disorders include anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder. If you or someone you know experiences the symptoms listed below, it could be a sign of an eating disorder—call a health provider right away for help. -

Relationship Between the Postoperative Delirium And

Theory iMedPub Journals Journal of Neurology and Neuroscience 2020 www.imedpub.com Vol.11 No.5:332 ISSN 2171-6625 DOI: 10.36648/2171-6625.11.1.332 Relationship Between the Postoperative Delirium and Dementia in Elderly Surgical Patients: Alzheimer’s Disease or Vascular Dementia Relevant Study Jong Yoon Lee1*, Hae Chan Ha2, Noh June Mo2, Hong Kyung Ho2 1Department of Neurology, Seoul Chuk Hospital, Seoul, Korea. 2Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Seoul Chuk Hospital, Seoul, Korea. *Corresponding author: Jong Yoon Lee, M.D. Department of Neurology, Seoul Chuk Hospital, 8, Dongsomun-ro 47-gil Seongbuk-gu Seoul, Republic of Korea, Tel: + 82-1599-0033; E-mail: [email protected] Received date: June 13, 2020; Accepted date: August 21, 2020; Published date: August 28, 2020 Citation: Lee JY, Ha HC, Mo NJ, Ho HK (2020) Relationship Between the Postoperative Delirium and Dementia in Elderly Surgical Patients: Alzheimer’s Disease or Vascular Dementia Relevant Study. J Neurol Neurosci Vol.11 No.5: 332. gender and CRP value {HTN, 42.90% vs. 43.60%: DM, 45.50% vs. 33.30%: female, 27.2% of 63.0 vs. male 13.8% Abstract of 32.0}. Background: Delirium is common in elderly surgical Conclusion: Dementia play a key role in the predisposing patients and the etiologies of delirium are multifactorial. factor of POD in elderly patients, but found no clinical Dementia is an important risk factor for delirium. This difference between two subgroups. It is estimated that study was conducted to investigate the clinical relevance AD and VaD would share the pathophysiology, two of surgery to the dementia in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) or subtype dementia consequently makes a similar Vascular dementia (VaD). -

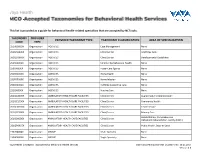

This List Is Provided As a Guide for Behavioral Health-Related Specialties That Are Accepted by Nctracks

This list is provided as a guide for behavioral health-related specialties that are accepted by NCTracks. TAXONOMY PROVIDER PROVIDER TAXONOMY TYPE TAXONOMY CLASSIFICATION AREA OF SPECIALIZATION CODE TYPE 251B00000X Organization AGENCIES Case Management None 261QA0600X Organization AGENCIES Clinic/Center Adult Day Care 261QD1600X Organization AGENCIES Clinic/Center Developmental Disabilities 251S00000X Organization AGENCIES Community/Behavioral Health None 253J00000X Organization AGENCIES Foster Care Agency None 251E00000X Organization AGENCIES Home Health None 251F00000X Organization AGENCIES Home Infusion None 253Z00000X Organization AGENCIES In-Home Supportive Care None 251J00000X Organization AGENCIES Nursing Care None 261QA3000X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Augmentative Communication 261QC1500X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Community Health 261QH0100X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Health Service 261QP2300X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Primary Care Rehabilitation, Comprehensive 261Q00000X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Outpatient Rehabilitation Facility (CORF) 261QP0905X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Public Health, State or Local 193200000X Organization GROUP Multi-Specialty None 193400000X Organization GROUP Single-Specialty None Vaya Health | Accepted Taxonomies for Behavioral Health Services Claims and Reimbursement | Content rev. 10.01.2017 Version -

Vascular Dementia Vascular Dementia

Vascular Dementia Vascular Dementia Other Dementias This information sheet provides an overview of a type of dementia known as vascular dementia. In this information sheet you will find: • An overview of vascular dementia • Types and symptoms of vascular dementia • Risk factors that can put someone at risk of developing vascular dementia • Information on how vascular dementia is diagnosed and treated • Information on how someone living with vascular dementia can maintain their quality of life • Other useful resources What is dementia? Dementia is an overall term for a set of symptoms that is caused by disorders affecting the brain. Someone with dementia may find it difficult to remember things, find the right words, and solve problems, all of which interfere with daily activities. A person with dementia may also experience changes in mood or behaviour. As the dementia progresses, the person will have difficulties completing even basic tasks such as getting dressed and eating. Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia are two common types of dementia. It is very common for vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease to occur together. This is called “mixed dementia.” What is vascular dementia?1 Vascular dementia is a type of dementia caused by damage to the brain from lack of blood flow or from bleeding in the brain. For our brain to function properly, it needs a constant supply of blood through a network of blood vessels called the brain vascular system. When the blood vessels are blocked, or when they bleed, oxygen and nutrients are prevented from reaching cells in the brain. As a result, the affected cells can die. -

Eating Disorders

Eating Disorders NDSCS Counseling Services hopes the following information will help you gain a better understanding of eating disorders. If you believe you or someone you know is experiencing related concerns and would like to visit with a counselor, please call NDSCS Counseling Services for an appointment - 701.671.2286. Definition There is a commonly held view that eating disorders are a lifestyle choice. Eating disorders are actually serious and often fatal illnesses that cause severe disturbances to a person’s eating behaviors. Obsessions with food, body weight, and shape may also signal an eating disorder. Common eating disorders include anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder. Signs and Symptoms Anorexia nervosa People with anorexia nervosa may see themselves as overweight, even when they are dangerously underweight. People with anorexia nervosa typically weigh themselves repeatedly, severely restrict the amount of food they eat, and eat very small quantities of only certain foods. Anorexia nervosa has the highest mortality rate of any mental disorder. While many young women and men with this disorder die from complications associated with starvation, others die of suicide. In women, suicide is much more common in those with anorexia than with most other mental disorders. Symptoms include: • Extremely restricted eating • Extreme thinness (emaciation) • A relentless pursuit of thinness and unwillingness to maintain a normal or healthy weight • Intense fear of gaining weight • Distorted body image, a self-esteem -

Understanding Mental Health

UNDERSTANDING MENTAL HEALTH WHAT IS MENTAL HEALTH? Our mental health directly influences how we think, feel and act: it also affects our physical health. Work, in fact, is actually one of the best things for protecting our mental health, but it can also adversely affect it. Good mental health and well-being is not an on-off A person’s mental health moves back and forth along this range during experience. We can all have days, weeks or months their lifetime, in response to different stressors and circumstances. At where we feel resilient, strong and optimistic, the green end of the continuum, people are well; showing resilience regardless of events or situations. Often that can and high levels of wellbeing. Moving into the yellow area, people be mixed with or shift to a very different set of may start to have difficulty coping. In the orange area, people have thoughts, feelings and behaviours; or not feeling more difficulty coping and symptoms may increase in severity and resilient and optimistic in just one or two areas of frequency. At the red end of the continuum, people are likely to be our life. For about twenty-five per cent of us, that experiencing severe symptoms and may be at risk of self-harm or may shift to having a significant impact on how suicide. we think, feel and act in many parts of our lives, including relationships, experiences at work, sense of connection to peer groups and our personal sense of worth, physical health and motivation. This could lead to us developing a mental health condition such as anxiety, depression, substance misuse. -

Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia

REVIEW ARTICLE published: 07 May 2012 doi: 10.3389/fneur.2012.00073 Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia J. Cerejeira1*, L. Lagarto1 and E. B. Mukaetova-Ladinska2 1 Serviço de Psiquiatria, Centro Hospitalar Psiquiátrico de Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal 2 Institute for Ageing and Health, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK Edited by: Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD), also known as neuropsy- João Massano, Centro Hospitalar de chiatric symptoms, represent a heterogeneous group of non-cognitive symptoms and São João and Faculty of Medicine University of Porto, Portugal behaviors occurring in subjects with dementia. BPSD constitute a major component of Reviewed by: the dementia syndrome irrespective of its subtype. They are as clinically relevant as cog- Federica Agosta, Vita-Salute San nitive symptoms as they strongly correlate with the degree of functional and cognitive Raffaele University, Italy impairment. BPSD include agitation, aberrant motor behavior, anxiety, elation, irritability, Luísa Alves, Centro Hospitalar de depression, apathy, disinhibition, delusions, hallucinations, and sleep or appetite changes. Lisboa Ocidental, Portugal It is estimated that BPSD affect up to 90% of all dementia subjects over the course of their *Correspondence: J. Cerejeira, Serviço de Psiquiatria, illness, and is independently associated with poor outcomes, including distress among Centro Hospitalar Psiquiátrico de patients and caregivers, long-term hospitalization, misuse of medication, and increased Coimbra, Coimbra 3000-377, Portugal. health care costs. Although these symptoms can be present individually it is more common e-mail: [email protected] that various psychopathological features co-occur simultaneously in the same patient.Thus, categorization of BPSD in clusters taking into account their natural course, prognosis, and treatment response may be useful in the clinical practice. -

Coding for Dementia & Other Unspecified Conditions

www.hospicefundamentals.com Hospice Fundamentals Subscriber Webinar September 2014 Coding For Dementia & Other Unspecified Conditions Judy Adams, RN, BSN, HCS-D, HCS-O AHIMA Approved ICD-10-CM Trainer September 2014 Transmittal 3022 • CMS released Transmittal 3022, Hospice Manual Update for Diagnosis Reporting and Filing Hospice Notice of Election and Termination or Revocation of Election on August 22, 2014 to replace Transmittal 8877. • Purpose: to provide a manual update and provider education for new editing for principal diagnoses that are not appropriate for reporting on hospice claims. • Our focus today is on the diagnosis portion of the transmittal. • Basis for the information • Per CMS: ICD-9-CM/ICD-10-CM Coding Guidelines state that codes listed under the classification of Symptoms, Signs, and Ill- defined Conditions are not to be used as principal diagnosis when a related definitive diagnosis has been established or confirmed by the provider. © Adams Home Care Consulting All Rights Reserved 2014 1 www.hospicefundamentals.com Hospice Fundamentals Subscriber Webinar September 2014 Policy • Effective with dates of service 10/1/14 and later. • The following principal diagnoses reported on the claim will cause claims to be returned to provider for a more definitive code: • “Debility” (799..3), malaise and fatigue (780.79) and “adult failure to thrive”(783.7)are not to be used as principal hospice diagnosis on the claim.. • Many dementia codes found in the Mental, Behavioral and neurodevelopment Chapter are typically manifestation codes and are listed as dementia in diseases classified elsewhere (294.10 and 294.11). Claims with these codes will be returned to provider with a notation “manifestation code as principal diagnosis”. -

Redalyc. Social Psychology of Mental Health: the Social Structure and Personality Prespective

Scientific Information System Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Esteban Sánchez Moreno, Ana Barrón López de Roda Social Psychology of Mental Health: The Social Structure and Personality Prespective The Spanish Journal of Psychology, vol. 6, núm. 1, mayo, 2003 Universidad Complutense de Madrid España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=17260102 The Spanish Journal of Psychology, ISSN (Printed Version): 1138-7416 [email protected] Universidad Complutense de Madrid España How to cite Complete issue More information about this article Journal's homepage www.redalyc.org Non-Profit Academic Project, developed under the Open Acces Initiative The Spanish Journal of Psychology Copyright 2003 by The Spanish Journal of Psychology 2003, Vol. 6, No. 1, 3-11 1138-7416 Social Psychology of Mental Health: The Social Structure and Personality Perspective Esteban Sánchez Moreno and Ana Barrón López de Roda Complutense University of Madrid Previous research has revealed a persistent association between social structure and mental health. However, most researchers have focused only on the psychological and psychosocial aspects of that relationship. The present paper indicates the need to include the social and structural bases of distress in our theoretical models. Starting from a general social and psychological model, our research considered the role of several social, environmental, and structural variables (social position, social stressors, and social integration), psychological factors (self-esteem), and psychosocial variables (perceived social support). The theoretical model was tested working with a group of Spanish participants (N = 401) that covered a range of social positions. The results obtained using structural equation modeling support our model, showing the relevant role played by psychosocial, psychological and social, and structural factors.