MSU Economic Impact

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wrestling, Adventure/ Collect, After 7:30 Pm Best, (202) Tess - Give It Up! He's Mine! Lance's Love

Ho Local restaurant to reopen Drunk students learn the hard Ram Women's basketball team JO'S on weekend nights, p. 5 Driving way, p. 16 Jam losses to VCU, p. 21 ■ . - THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 4,1988 JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY VOL. 65 NO. 34 . n the religion of pleasure, each finds his own Mecca. For Last year Spring Break revenues in the Florida resort most students at JMU and elsewhere, Mecca lies somewhere south. community plummeted S55 million from the year before because The owner of Valley Mall's Travel Pros said Florida, the of the defensive atmosphere generated by the police, said Gregg Bahamas and Cancun rate high with the JMU jet set, although Newell, the executive director of the Fort Laudcrdalc '88 most of his tours are solidly booked. Those few spaces left are Committee. priced "way out of range," said Fred Schacfer. "This year they [the police] are going to be diplomats. They The west coast of Florida is a surprisingly big seller this year didn't treat people like tourists last year." he said. at Travel Pros. The old standards, Daytona Beach and Fort "The mayor is an anti-Spring-Brcakcr," Newell said, but has Laudcrdalc, lag behind. given his support to the committee which comprises 25 of the Officials in Laudcrdalc, recognizing its dwindling popularity largest hotels and night clubs in the area. with the college crowd aficr a police crackdown last year, arc "We're saying this is the place where it started Come on reverting to form. back. We want you," he said. The "Berlin Wall," separating students on the beach from the Area motels are halving their rates said Newell, who hopes to civilized world in Fort Laudcrdalc, is coming down this year while see the Fort Laudcrdalc business community make a profit of SI 10 other Florida communities arc gearing up. -

Testimony, Shelby Emmett, Director Center to Protect Free Speech

Testimony, Shelby Emmett, Director Center to Protect Free Speech My name is Shelby Emmett. I am the Director of the ALEC Center to Protect Free Speech. I am also a Michigan native, and a proud graduate of James Madison College at Michigan State University. I received dual bachelors in Political Theory & Constitutional Democracy and Social Relations in 2006. JMC gave me a first-hand experience in “the marketplace of ideas” debating everything from gay marriage and affirmative action, to the racial elements of hurricane Katrina and whether nation states or a “citizen of the world” approach is the best public policy for the 21st century. I can tell you I was routinely offended and made uncomfortable in the classroom—and likely offended quite a few of my peers and professors along the way. And although I hate to admit it at times, often I found myself changing my mind on what I thought were established truths. James Madison College forced me out of my safe space and helped me to develop the critical thinking skills necessary to flesh out and counter arguments instead of simply ignoring or attempting to shut down opinions I disagreed with. I am forever grateful for the quality education I received from MSU and I want future graduates of James Madison College and all of Michigan’s public colleges and universities to have the same opportunity to confront ideas as I did. With that said, I want to spend my testimony talking about two very important aspects of this bill: the need to ensure all members of the community, not just students, understand the rules of the game; and the importance of ensuring any legislation passed to protect speech on campus does not unintentionally chill speech or make students or student groups fear whether an administrator will unlawfully haul them into a campus disciplinary hearing. -

Dennis C. Rasmussen CV

Dennis C. Rasmussen Syracuse University Department of Political Science Updated February 2020 100 Eggers Hall Syracuse, NY 13244 315-443-5877 [email protected] maxwell.syr.edu/psc/Rasmussen,_Dennis EDUCATION Duke University Ph.D., Political Science, 2005 M.A., Political Science, 2002 Dissertation: “The Problems and Promise of Commercial Society: Adam Smith’s Response to Rousseau” Committee: Ruth Grant (chair), Michael Gillespie, Tom Spragens, Neil De Marchi Michigan State University B.A., Political Theory and Constitutional Democracy (James Madison College), 2000 Graduated summa cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa, Honors College ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS Syracuse University Professor, Department of Political Science, Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs, 2019-present Senior Research Associate, Campbell Public Affairs Institute, 2019-present Tufts University Professor and Chair, Department of Political Science, 2018-2019 Associate Professor, Department of Political Science, 2014-2018 Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, 2009-2014 University of Houston Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science and the Honors College, 2008-2009 Brown University Postdoctoral Research Associate, Political Theory Project, 2007-2008 Bowdoin College Visiting Assistant Professor, Department of Government, 2005-2007 Rasmussen 2 PUBLICATIONS Books Fears of a Setting Sun: The Disillusionment of the American Founders. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, forthcoming. The Infidel and the Professor: David Hume, Adam Smith, and the Friendship -

News and Notes

News and Notes New Appointments University; formerly of the University of Michigan. Samuel H. Beer, Thomas P. O'Neill, Jr. Michael M. Gunter, full professor, Ten- Professor of American Politics, Boston nessee Tech University. College; formerly Eaton Professor of the Science of Government, Harvard Univer- John David Harman, assistant professor, sity. St. John Fisher College, Rochester, New York. Anne O'Meara Bowman, assistant pro- fessor, University of South Carolina; for- William A. Hazleton, assistant professor, merly of Texas A&M. Miami University, Oxford, Ohio; formerly a visiting appointment at Miami Univer- C. Anthony Broh, assistant professor, sity. Rutgers University; formerly of Columbia University. Richard K. Herrmann, assistant profes- sor, Ohio State University. T. R. Carr, assistant professor, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville; formerly at Milton Heumann, professor of political Texas Tech University. science, Rutgers University; formerly of the University of Michigan. Susan J. Carroll, assistant professor, Eagleton Institute, Rutgers University; Roger E. Kanet, University of Illinois at formerly of George Washington Univer- Urbana-Champaign, has been appointed sity. an associate of the Center for Advanced Study of the University of Illinois for Jimmy D. Case, assistant professor, Sul 1981-82, where he will be engaged in Ross State University, Texas. full-time research on a project dealing Donald K. Crone, assistant professor, with Soviet and East European relations James Madison College, Michigan State with Africa. University; formerly of the University of David R. Mares, acting assistant profes- British Columbia. sor, University of California, San Diego; Alan Chartocck is the first individual to formerly El Colegio de Mexico. hold a joint appointment from two SUNY Connie Mauney, assistant professor, campuses. -

Reps. Meadows, Dean, Lemmons, Polidori, Kathleen Law, Clack

Reps. Meadows, Dean, Lemmons, Polidori, Kathleen Law, Clack, Hammon, Hammel, Caswell, Pearce, Hansen, Marleau, Garfield, Meltzer, Vagnozzi, Warren, Mayes, Byrum, Sak, Donigan, Valentine, Spade, Proos, Cushingberry, Robert Jones, Meisner, Ball, Pastor, Johnson, Rick Jones, Steil, Hopgood, Gonzales, Accavitti, Bieda, Tobocman, Miller, Constan, LeBlanc, Byrnes, Palmer, Rocca, Alma Smith and Condino offered the following resolution: House Resolution No. 170. A resolution commemorating the 40th anniversary of Michigan State University’s James Madison College. Whereas, It is with admiration for this nationally recognized institution that we commemorate the 40th anniversary of James Madison College at Michigan State University. Rightfully known as one of MSU’s crown jewels, James Madison College has offered its students the best of both worlds throughout the last forty years, a small residential college within a large university. The results have been as effective as they have been far-reaching. We commend everyone who has contributed to this inspiring success; and, Whereas, All across our nation, graduates of James Madison College have taken their well deserved place in courtrooms, boardrooms, the halls of government, and in every other professional arena. In Michigan, alumni are serving in the House of Representatives and the Executive Office, as well as in law, banking, real estate, and countless other fields. James Madison students are having a profound and positive impact throughout the world and are bringing great pride to that “little school that thought it could”; and, Whereas, From 1960 to 1966, enrollment grew 75 percent at MSU. President Hannah, administrators, and faculty created James Madison College to retain the positive aspects of the small university of the 1950s. -

42 Annual Meetings of the History of Economics Society

HES History of Economics Society historyofeconomics.org 42nd Annual Meetings of the History of Economics Society Conference Program Michigan State University East Lansing, MI June 26-29, 2015 2 History of Economics Society Executive Committee President Jeff Biddle, Michigan State University President-Elect Mauro Boianovsky, Universidade de Brasilia Vice-President Maria Pia Paganelli, Trinity University Secretary Marianne Johnson, University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh Treasurer Spencer Banzhaf, Georgia State University Past President Robert Leonard, Université du Québec à Montréal Past Past President Margaret Schabas, University of British Columbia Elected Committee Members John Berdell, DePaul University (2018) Beatrice Cherrier, Université de Caen (2018) Ivan Moscati, University of Insubria (2017) Rebecca Gomez-Betancourt, Université Lumière Lyon 2 (2017) Editor Stephen Meardon, Bowdoin College Journal of the History of Economic Thought List Moderator Humberto Barreto, DePauw University Archivist Craufurd Goodwin, Duke University 3 Prizes and Honors Distinguished Fellow Roger E. Backhouse Professor of the History and Philosophy of Economics University of Birmingham Presidential Address Robert Leonard Professor of Economics Université du Québec à Montréal Joseph Dorfman Best Dissertation Prize Manuela Fernández Pinto “Learning from Ignorance: Agnotology’s Challenge to Philosophy of Science” University of Notre Dame, 2014 HES Best Article Award Kevin D. Hoover “On the Reception of Haavelmo’s Econometric Thought”, Journal of the History of Economic Thought, vol. 36, no. 1 (2014) 4 Warren J. and Sylvia J. Samuels Young Scholars HES 2015 These awards are made possible thanks to the generous donation of Warren J. and Sylvia J. Samuels. Subsequent donors have allowed us to expand the offerings, and more contributions would be appreciated. -

News Release

NEWS RELEASE Contact: Sandy Adkins Communications Specialist 757.259.1515 [email protected] Texas Chief Justice to Lead National Court Organizations Wallace B. Jefferson Known for Integrity and Dedication to Nation’s Judiciary Williamsburg, Va. (Aug. 4, 2010) — Texas Chief Justice Wallace B. Jefferson has been elected chair of the Board of Directors of the National Center for State Courts (NCSC). He also has been named president of the Conference of Chief Justices (CCJ), a national organization that represents the top judges of the 50 states and the U.S. territories, and of which NCSC serves as executive staff. Both positions are one-year terms. The appointments were made at the National Center’s Board of Directors meeting and the CCJ and Conference of State Court Administrators Annual Conference, both of which were held during the last week of July in Vail, Colo. “During his years as an attorney in private practice, Chief Justice Jefferson earned a reputation for appellate excellence,” said Mary C. McQueen, NCSC president. “His years on the bench have earned him a reputation for integrity and objectivity. These characteristics, coupled with his dedication to the betterment of the nation’s judiciary, will make him an excellent leader for both NCSC and CCJ.” Chief Justice Jefferson was the first African-American to sit on the Supreme Court of Texas, to which he was appointed by Gov. Rick Perry in March 2001. He was elected to the Supreme Court in a statewide race in November 2002. Two years later, Gov. Perry appointed him chief justice to fill a vacancy. -

Michigan State University Commencement Spring 2021

COMMENCEMENT CEREMONIES SPRING 2021 “Go forth with Spartan pride and confdence, and never lose the love for learning and the drive to make a diference that brought you to MSU.” Samuel L. Stanley Jr., M.D. President Michigan State University Photo above: an MSU entrance marker of brick and limestone, displaying our proud history as the nation’s pioneer land-grant university. On this—and other markers—is a band of alternating samara and acorns derived from maple and oak trees commonly found on campus. This pattern is repeated on the University Mace (see page 13). Inside Cover: Pattern of alternating samara and acorns. Michigan State University photos provided by University Communications. ENVIRONMENTAL TABLE OF CONTENTS STEWARDSHIP Mock Diplomas and the COMMENCEMENT Commencement Program Booklet 3-5 Commencement Ceremonies Commencement mock diplomas, 6 The Michigan State University Board of Trustees which are presented to degree 7 Michigan State University Mission Statement candidates at their commencement 8–10 Congratulatory Letters from the President, Provost, and Executive Vice President ceremonies, are 30% post-consumer 11 Michigan State University recycled content. The Commencement 12 Ceremony Lyrics program booklet is 100% post- 13 University Mace consumer recycled content. 14 Academic Attire Caps and Gowns BACCALAUREATE DEGREES Graduating seniors’ caps and gowns 16 Honors and master’s degrees’ caps and 17-20 College of Agriculture and Natural Resources gowns are made of post-consumer 21-22 Residential College in the Arts and Humanities recycled content; each cap and 23-25 College of Arts and Letters gown is made of a minimum of 26-34 The Eli Broad College of Business 23 plastic bottles. -

Robert B. Brown Collection UA.17.424

Robert B. Brown Collection UA.17.424 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on March 25, 2019. Finding aid written in English. Describing Archives: A Content Standard Michigan State University Archives and Historical Collections Conrad Hall 943 Conrad Road, Room 101 East Lansing , MI 48824 [email protected] URL: http://archives.msu.edu/ Robert B. Brown Collection UA.17.424 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical Note .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Contents Note ............................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 4 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 5 Film .............................................................................................................................................................. 5 Negatives and Color Positives ................................................................................................................... -

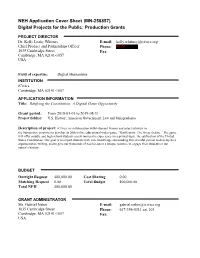

NEH Application Cover Sheet Digital Projects for the Public

NEH Application Cover Sheet (MN-258857) Digital Projects for the Public: Production Grants PROJECT DIRECTOR Dr. Kelly Leahy Whitney E-mail: [email protected] Chief Product and Partnerships Officer Phone: (b) (6) 1035 Cambridge Street Fax: Cambridge, MA 02141-1057 USA Field of expertise: Digital Humanities INSTITUTION iCivics Cambridge, MA 02141-1057 APPLICATION INFORMATION Title: Ratifying the Constitution: A Digital Game Opportunity Grant period: From 2018-01-01 to 2019-08-31 Project field(s): U.S. History; American Government; Law and Jurisprudence Description of project: iCivics, in collaboration with Filament Games and select scholars in the humanities, proposes to develop its 20th online educational video-game: "Ratification: The Great Debate.” The game will offer middle and high school students a new immersive experience on a pivotal topic: the ratification of the United States Constitution. Our goal is to impart students with core knowledge surrounding this eventful period, to develop their argumentative writing, and to give our thousands of teacher-users a unique resource to engage their students in our nation’s history. BUDGET Outright Request 400,000.00 Cost Sharing 0.00 Matching Request 0.00 Total Budget 400,000.00 Total NEH 400,000.00 GRANT ADMINISTRATOR Mr. Gabriel Neher E-mail: [email protected] 1035 Cambridge Street Phone: 617-356-8311 ext.103 Cambridge, MA 02141-1057 Fax: USA Table of Contents Application Narrative A) Nature of the request . 1 B) Humanities content . 1 C) Project format . 8 D) Audience and distribution . 9 E) Project evaluation and testing . 10 F) Right, permissions, and licensing. 11 G) Humanities advisers . -

Yale University Library Digital Repository Contact Information

Yale University Library Digital Repository Collection Name: Henry A. Kissinger papers, part II Series Title: Series II. Government Service Box: 303 Folder: 5 Folder Title: Stevenson, Charles Persistent URL: http://yul-fi-uat1.library.yale.internal/catalog/digcoll:560273 Repository: Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library Contact Information Phone: (203) 432-1735 Email: [email protected] Mail: Manuscripts and Archives Sterling Memorial Library Sterling Memorial Library P.O. Box 208240 New Haven, CT 06520 Your use of Yale University Library Digital Repository indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use http://guides.library.yale.edu/about/policies/copyright Find additional works at: http://yul-fi-uat1.library.yale.internal LG1 • JUN 19 1967 18 June 1967 Professor Neustadt should have sent over to your office my paper, "Formulation of American Foreign Policy in Crisis Situations," which I wrote for his seminar, Gov 254. When I talked to you in March, you expressed an interest in seeing this paper when it was finished. Ply original intention to focus on "bureaucratic-pragmatic style" has been somewhat diverted to an attempt to suggest elements in a typology of crises. The broader theme of style still remains, however, the concern underlying my whole current approach to a thesis topic. I would appreciate it if you would read this paper and then give me your comments, especially with regard to the following points: Is there something grossly wrong with this approach -- such as dangerous oversimplification, naivete, unsupportable assertions, or poorly phrased categories? Even if so, is there any merit in trying to continue this effort and expand it into some kind of thesis? What omissions, inclusions, or revisions would put me on the track of a worthwhile thesis? If you should wish to make your comments by letter before I return to Cambridge in mid-September, I would certainly be grateful. -

1959 COLUMBIA UNION CONFERENCE of Seventh-Day Adventists L

, Digitized by the Center for Adventist Research at the light the wo A year'of pu where He, "I am the Way," has gone before; A year of following- sometimes afar off, sometimes more closely,-- "IN HIS STEPS." Digitized by the Center for Adventist Research Digitized by the Center for Adventist Research Digitized by the Center for Adventist Research The President's Message Hold your head up, throw your shoulders back, stand erect, and keep a level eye. You are a prince, the son of King Emmanuel. Royal blood is coursing through your veins. You have an honor, a mission, and a responsibility above that of all other men. You were born to live above the world, to be a leader of men, and to die for your King if necessary. Wave aloft the banner of your King, faithfully perform you mission as only a prince knows how. Dedicate your life to unselfish service for the subjects of your Father's royal kingdom. Stoop not to pecuniary gain, neither be swept away by the vain allurements of this momentary world. Always remember that you are heir to an everlasting kingdom. William Sandborn, Ed. D. DRUILLARD LIBRARY A DISON COLLEGE- TENN. 4 Digitized by the Center for Adventist Research The Dean's Message Another school year has passed into the pages of history, and as we view these pages we realize more than ever before the many marvelous blessings that have been ours. We can never forget the inspiring weeks of prayer, the lngathering of funds for the Lord's work, the socials of various kinds, the vesper hours, and the Sabbath services.