THE SELF AS PROJECT from Laurie Ouellette, Lifestyle TV

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beat the Heat

To celebrate the opening of our newest location in Huntsville, Wright Hearing Center wants to extend our grand openImagineing sales zooming to all of our in offices! With onunmatched a single conversationdiscounts and incomparablein a service,noisy restaraunt let us show you why we are continually ranked the best of the best! Introducing the Zoom Revolution – amazing hearing technology designed to do what your own ears can’t. Open 5 Days a week Knowledgeable specialists Full Service Staff on duty daily The most advanced hearing Lifetime free adjustments andwww.annistonstar.com/tv cleanings technologyWANTED onBeat the market the 37 People To Try TVstar New TechnologyHeat September 26 - October 2, 2014 DVOTEDO #1YOUTHANK YOUH FORAVE LETTING US 2ND YEAR IN A ROW SERVE YOU FOR 15 YEARS! HEARINGLeft to Right: A IDS? We will take them inHEATING on trade & AIR for• Toddsome Wright, that NBC will-HISCONDITIONING zoom through• Dr. Valerie background Miller, Au. D.,CCC- Anoise. Celebrating• Tristan 15 yearsArgo, in Business.Consultant Established 1999 2014 1st Place Owner:• Katrina Wayne Mizzell McSpadden,DeKalb ABCFor -County HISall of your central • Josh Wright, NBC-HISheating and air [email protected] • Julie Humphrey,2013 ABC 1st-HISconditioning Place needs READERS’ Etowah & Calhoun CHOICE!256-835-0509• Matt Wright, • OXFORD ABCCounties-HIS ALABAMA FREE• Mary 3 year Ann warranty. Gieger, ABC FREE-HIS 3 years of batteries with hearing instrument purchase. GADSDEN: ALBERTVILLE: 6273 Hwy 431 Albertville, AL 35950 (256) 849-2611 110 Riley Street FORT PAYNE: 1949 Gault Ave. N Fort Payne, AL 35967 (256) 273-4525 OXFORD: 1990 US Hwy 78 E - Oxford, AL 36201 - (256) 330-0422 Gadsden, AL 35901 PELL CITY: Dr. -

TLC PRIMETIME HIGHLIGHTS: Weeks of October 13Th and 20Th (As of 10.9.14)

TLC PRIMETIME HIGHLIGHTS: Weeks of October 13th and 20th (as of 10.9.14) Below please find program highlights for TLC’s primetime schedule for the weeks of October 13th and 20th. There are preview episodes and episodic photography available for select programs/episodes on press.discovery.com. Please check with us for further information. TLC PRESS CONTACT: Jordyn Linsk: 240-662-2421 [email protected] TH WEEK OF OCTOBER 13 (as of 10.9.14) OF NOTE THIS WEEK: Special 90 DAY FIANCE – SEASON 1 WHERE ARE THEY NOW? – Sunday, October 19 Season Premieres 90 DAY FIANCE – Sunday, October 19 MY FIVE WIVES – Sunday, October 19 TUESDAY, OCTOBER 14 9:00PM ET/PT 19 KIDS & COUNTING – “WEDDING COUNTDOWN!” With only one week to go, the Duggars are counting down the days until Jill’s wedding! From securing a rehearsal getaway car to filling up their new home with furniture purchased at a local auction, this super- size family is in full-on wedding mode. WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 15 9:00PM ET/PT EXTREME CHEAPSKATES – “FATHER KNOWS DEBT” Patriarch Raul Pinto scours through vacuum canisters at the car wash in hopes of finding spare change. And Kia Cambridge limits herself to one piece of gum every three days. 9:30PM ET/PT EXTREME CHEAPSKATES – “POOL RULES: NO SPENDING” Homemaker Jeni Cox goes to sporting good stores, using the exercise equipment on display in lieu of a gym membership. Realtor Lisa DiMercurio spends just three dollars to stage and sell her homes. 10:00PM ET/PT OUTRAGEOUS 911 – “THE MEAN LADY NEXT DOOR” This episode features a woman who doesn’t like how her false lashes look as well as a mean old lady who won’t give back the neighborhood kids their ball. -

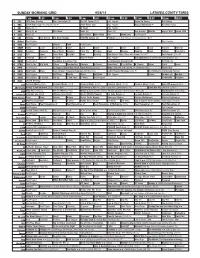

Sunday Morning Grid 9/28/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 9/28/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Paid Program Tunnel to Towers Bull Riding 4 NBC 2014 Ryder Cup Final Day. (4) (N) Å 2014 Ryder Cup Paid Program Access Hollywood Å Red Bull Series 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Sea Rescue Wildlife Exped. Wild Exped. Wild 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Winning Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Green Bay Packers at Chicago Bears. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Cooking Cook Kitchen Ciao Italia 28 KCET Hi-5 Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Rick Steves’ Italy: Cities of Dreams (TVG) Å Over Hawai’i (TVG) Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program The Specialist ›› (1994) Sylvester Stallone. (R) 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) La Arrolladora Banda Limón Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program 12 Dogs of Christmas: Great Puppy Rescue (2012) Baby’s Day Out ›› (1994) Joe Mantegna. -

715-479-5752 • Siding Garages • Plumbing • Electrical • Heavy Equipment Operation • Roofing Remodeling • Roofing DAN’S DOCK 2255 Hwy

PAID ECRWSS Eagle River PRSRT STD PRSRT U.S. Postage Permit No. 13 POSTAL PATRON POSTAL Saturday, Saturday, Sept. 20, 2014 20, Sept. (715) 479-4421 sidency restrictions apply. See dealer for details. ome customers will not qualify. Take delivery by 09-30-2014. AND THE THREE LAKES NEWS THE AND A SPECIAL SECTION OF THE VILAS COUNTY NEWS-REVIEW THE VILAS COUNTY SECTION OF SPECIAL A NORTH WOODS NORTH THE PAUL BUNYAN OF NORTH WOODS ADVERTISING WOODS OF NORTH BUNYAN THE PAUL Residency restrictions apply. See dealer for details. Not available with finance or lease offers. Take delivery by 09-30-2014. Re © Eagle River 1.0% APR for 60 months qualified buyers. Monthly payment is $16.67 every $1,000 you finance. Example down payment: 18%. S Publications, Inc. 1972 Inc. Publications, 715-479-442 Fax 715-479-6242 P.O. Box 1929 Eagle River, WI 54521 $11 – 25 words or less (one time). Additional word 30¢, payable in advance. Visa/MasterCard/ CLASSIFIEDS Discover ————————————————— ————————————————— MISCELLANEOUS FOR SALE: Energy King wood-burn- ————————————————— ing, hot-water furnace, $300. (715) 479- ARE YOU NEW TO THE EAGLE RIV- 1620. 1p-9449-28 ER, THREE LAKES, PHELPS, ————————————————— CONOVER, LAND O’ LAKES AND ST. LOG JAMBOREE: Ewen, Mich., Sept. GERMAIN AREA? Call Nicolet Wel- 26 & 27, entertainment & yard sales. come Service, at 1-(800) 513-1350. 1p-9456-28 Also Bundles of Joy baby packet for ————————————————— newborns to three months. 7315-tfc FOR SALE: 60,000-Btu propane fur- ————————————————— nace, top-side heat supply, electronic PERMANENT SUSPENDED OVER- ignitor, good condition, almost like new. -

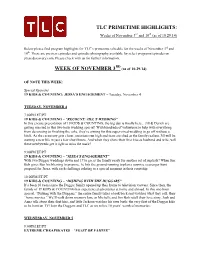

TLC PRIMETIME HIGHLIGHTS: Weeks of November 3Rd and 10Th (As of 10.29.14)

TLC PRIMETIME HIGHLIGHTS: Weeks of November 3rd and 10th (as of 10.29.14) Below please find program highlights for TLC’s primetime schedule for the weeks of November 3rd and 10th. There are preview episodes and episodic photography available for select programs/episodes on press.discovery.com. Please check with us for further information. RD WEEK OF NOVEMBER 3 (as of 10.29.14) OF NOTE THIS WEEK: Special Episodes 19 KIDS & COUNTING: JESSA’S ENGAGEMENT – Tuesday, November 4 TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 4 7:00PM ET/PT 19 KIDS & COUNTING – “RECOUNT: JILL’S WEDDING” In this encore presentation of 19 KIDS & COUNTING, the big day is finally here... Jill & Derick are getting married in this two-hour wedding special! With hundreds of volunteers to help with everything from decorating to finishing the cake, they’re aiming for this super-sized wedding to go off without a hitch. As the ceremony gets closer, emotions run high and tears are shed as the family realizes Jill will be starting a new life in just a few short hours. And when they share their first kiss as husband and wife, will these newlyweds get it right or miss the mark? 9:00PM ET/PT 19 KIDS & COUNTING – “JESSA’S ENGAGEMENT” With two Duggar weddings down and 17 to go, is the family ready for another set of nuptials? When Jim Bob gives Ben his blessing to propose, he hits the ground running to plan a surprise scavenger hunt proposal for Jessa, with each challenge relating to a special moment in their courtship. 10:00PM ET/PT 19 KIDS & COUNTING – “DISHING WITH THE DUGGARS” It’s been 10 years since the Duggar family opened up their home to television viewers. -

A New Chapter

FINAL-1 Sat, Nov 30, 2019 4:06:52 PM tvupdateYour Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment For the week of December 8 - 14, 2019 A new chapter Jacqueline Toboni stars in “The L Word: Generation Q” INSIDE •Sports highlights Page 2 •TV Word Search Page 2 •Family Favorites Page 4 •Hollywood Q&A Page14 Showtime is rebooting one of its most beloved shows with “The L Word: Generation Q,” premiering Sunday, Dec. 8. The series features the return of original “The L Word” stars Jennifer Beals (“Flashdance,” 1983), Leisha Hailey (“Dead Ant,” 2017) and Katherine Moennig (“Ray Donovan”), as well as a few new faces, including Jacqueline Toboni (“Grimm”), Arienne Mandi (“The Vault”) and Leo Sheng (“Adam,” 2019). To advertise here WANTED MOTORCYCLES, SNOWMOBILES, OR ATVS GOLD/DIAMONDS please call ✦ 40 years in business; A+ rating with the BBB. ✦ For the record, there is only one authentic CASH FOR GOLD, Bay 4 (978) 946-2375 Group Page Shell PARTS & ACCESSORIES We Need: SALESMotorsports & SERVICE 5 x 3” Gold • Silver • Coins • Diamonds MASS. MOTORCYCLEWANTED1 x 3” We are the ORIGINAL and only AUTHENTIC SELLBUYTRADEINSPECTIONS CASH FOR GOLD on the Methuen line, above Enterprise Rent-A-Car at 527 So. Broadway, Rte. 28, Salem, NH • 603-898-2580 1615 SHAWSHEEN ST., TEWKSBURY, MA Open 7 Days A Week ~ www.cashforgoldinc.com 978-851-3777 WWW.BAY4MS.COM FINAL-1 Sat, Nov 30, 2019 4:06:53 PM COMCAST ADELPHIA 2 Sports Highlights Kingston CHANNEL Atkinson ESPN NESN Sunday 8:00 p.m. TNT Basketball NBA Football NCAA Division I Hockey NCAA Dartmouth at Salem Londonderry 9:00 a.m. -

Women in Power 147Per Mo

The Daily Home MOTORS TVhome 411 East St. N., Talladega November 16 - 22, 2014 1-256-362-2271 Finance Programs Available For Everyone! All Credit Warranty Applications On All Accepted Vehicles! •Good Credit •Bad Credit •No Credit Check us out at colonialmotors.biz 2013 TOYOTA COROLLA $ 83* 210per mo. 2014 CHEVY MALIBU $ 30* 325per mo. 2008 MAZDA RX8 $ 83* Women in Power 147per mo. CIA analyst Charleston Tucker (Katherine Heigl) 2011 NISSAN is great at her job, but her personal life is MAXIMA another story on “State of Affairs,” premiering $ 03* Monday at 9 p.m. on NBC. 293per mo. *Payment based on $2000 down cash or trade, 72 months 3.9% APR plus tax, title, DOC fees W.A.C. See salesperson for details. “Your Community Bank” TALLADEGA 120 E. North Street • (256) 362-2334 LINCOLN 44743 U.S. Hwy. 78 • (205) 763-7763 M e b er MUNFORD FDIC www.fnbtalladega.com 44388 Highway 21• (256) 358-9000 2 THE DAILY HOME / TV HOME Sun., Nov. 16, 2014 — Sat., Nov. 22, 2014 DISH AT&T DIRECTV CABLE CHARTER CHARTER PELL CITY PELL ANNISTON CABLE ONE CABLE TALLADEGA SYLACAUGA BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM CONVERSION CABLE COOSA SPORTS WBRC 6 6 7 7 6 6 6 6 AUTO RACING Tuesday WBIQ 10 4 10 10 10 10 12 a.m. ESPN2 Auburn Tigers at NASCAR WCIQ 7 10 4 Colorado Buffaloes (Live) WVTM 13 13 5 5 13 13 13 13 Sunday 2 a.m. ESPN2 New Mexico State WTTO 21 8 9 9 8 21 21 21 9 a.m. -

TV Listings FRIDAY, JULY 31, 2015

TV listings FRIDAY, JULY 31, 2015 16:00 Imogene 18:00 Raising Helen 20:00 She Wants Me 22:00 Jackass Presents: Bad Grandpa 01:00 Killing Season-18 03:00 Not Fade Away-PG15 05:00 A Secret Promise-PG15 07:00 Diana-PG15 09:00 Stolen Child-PG15 11:00 Diana-PG15 13:00 Step Up Revolution-PG15 15:00 Kon-Tiki-PG15 17:00 Stolen Child-PG15 19:00 Upside Down-PG15 21:00 Capital-PG15 23:00 End Of Watch-18 02:30 Scents And Sensibility 04:30 Begin Again 06:30 My Last Day Without You 08:30 Salinger 11:00 Battle Of The Year 13:00 Begin Again 14:45 Chasing Mavericks 16:45 Salinger 19:00 There Be Dragons 21:00 Casanova 23:00 He Got Game 01:00 Think Like A Man Too-PG15 03:00 Muppets Most Wanted-PG 05:00 Moms’ Night Out-PG 07:00 Percy Jackson: Sea Of Monsters-PG 09:00 The Lego Movie-PG 11:00 Hours-PG15 WORLD WAR Z ON OSN MOVIES ACTION HD 13:00 Draft Day-PG15 15:00 Grudge Match-PG15 17:00 The Lego Movie-PG 16:00 Live PGA European Tour 14:30 Pawn Stars 15:15 Ben 10: Omniverse 10:25 Nina Needs To Go 02:45 Art Attack 19:00 The Grand Budapest Hotel- 19:00 WWE Bottomline 15:00 Shipping Wars 15:40 Ninjago: Masters Of Spinjitzu 10:30 Jake And The Neverland Pirates Disney XD PG15 20:00 WWE Superstars 15:30 Shipping Wars 16:00 Matt Hatter New 10:55 Runaway Shuffle/Surfin’ The 06:00 The 7D 21:00 If I Stay-PG15 21:00 WWE Main Event 16:00 Alaska Off-Road Warriors 16:25 Steven Universe Whirlpool 06:10 Randy Cunningham: 9th Grade 23:00 Delivery Man-PG15 22:00 AFL Premiership 17:00 Counting Cars 16:36 Steven Universe 11:20 Doc McStuffins Ninja 17:30 Counting Cars 16:45 Teen -

GSN Edition 12-31-20

The MIDWEEK Tuesday, Dec. 31, 2013 Goodland1205 Main Avenue, Goodland, Star-News KS 67735 • Phone (785) 899-2338 $1 Volume 81, Number 105 12 Pages Goodland, Kansas 67735 inside today More local news, views from your Goodland Star-News Creeks around Sherman County ran high during a week in September when the by without the kind of flood damage experienced in parts of Colorado. Swim Club county saw six or more inches of rain over a three-day period. The county scraped Photos by Kevin Bottrell/The Goodland Star-News is top sports story of 2013 Giant storm is top story of 2013 The Goodland Swim Club The Goodland Star-News has se- of Wildlife, Parks and Tourism de- won just about everything lected 10 good, bad or just interest- cided to use water from that lake to this summer. Its success ing news stories that appeared in the keep Smoky Gardens filled as long was chosen as the top paper over the course of 2013. The as possible. sports story of 2013. top five stories appear below, with The department also decided to See Page 12 the first five appearing in the Friday, stock Smoky Gardens with fish. The Dec. 27, edition of the newspaper. first release of about 400 rainbow trout took place on Dec. 3. Fisher- One of the most talked ies Biologist Dave Spalsbury said about stories of the year the department will do at least one weather carried both good news more release in January or February, and1 bad news. and may release warm-water fish in report In the middle of an epic, years- the summer. -

P32 Layout 1

TUESDAY, JULY 21, 2015 TV PROGRAMS 03:25 Coronation Street 13:00 The Ellen DeGeneres Show 03:50 Ginoʼs Italian Escape 15:00 Red Band Society 04:20 Callie-Anne Cooks Into The 16:00 Emmerdale Wild 16:30 Coronation Street 05:15 Tom Daley Goes Global 17:00 The Ellen DeGeneres Show 00:10 Eastenders 00:50 Sabrina: Secrets Of A 06:10 The Hungry Sailors 19:00 Criminal Minds 00:40 Call The Midwife Teenage Witch 07:05 Coronation Street 20:00 State Of Affairs 01:35 Spies Of Warsaw 01:15 Sabrina: Secrets Of A 08:00 Ginoʼs Italian Escape 21:00 The Flash 03:10 Him & Her Teenage Witch 08:25 Callie-Anne Cooks Into The 22:00 The Americans 03:40 My Family 01:40 Wolfblood Wild 23:00 Defiance 04:15 The Weakest Link 02:30 Violetta 09:20 Peter Andreʼs 60 Minute 05:00 The Green Balloon Club 03:20 Sabrina: Secrets Of A Makeover 05:25 Mr Bloomʼs Nursery Teenage Witch 10:15 Brendanʼs Magical Mystery 05:45 Show Me Show Me 04:10 Wolfblood Tour 06:05 Nina And The Neurons: In 05:00 Violetta 10:40 The Chase The Lab 05:50 Mouk 11:35 The Hungry Sailors 01:00 Good Morning America 06:20 The Green Balloon Club 06:00 Lolirock 12:30 Tom Daley Goes Global 03:00 Castle 06:45 Mr Bloomʼs Nursery 06:25 Hank Zipzer 13:25 Emmerdale 05:00 Good Morning America 07:05 Nina And The Neurons: In 06:50 Girl Meets World 13:50 Brendanʼs Magical Mystery 07:00 Emmerdale The Lab 07:15 H2O: Just Add Water Tour 07:30 Coronation Street 07:20 The Weakest Link 07:40 Jessie 14:15 Coronation Street 08:00 The Ellen DeGeneres Show 08:05 Come Fly With Me 08:05 Wizards Of Waverly Place 14:40 The Chase -

TLC PRIMETIME HIGHLIGHTS: Weeks of November 17Th and 24Th (As of 11.17.14)

TLC PRIMETIME HIGHLIGHTS: Weeks of November 17th and 24th (as of 11.17.14) Below please find program highlights for TLC’s primetime schedule for the weeks of November 17th and 24th. There are preview episodes and episodic photography available for select programs/episodes on press.discovery.com. Please check with us for further information. TH WEEK OF NOVEMBER 17 (as of 11.11.14) OF NOTE THIS WEEK: Series Premieres RISKING IT ALL – Tuesday, November 18 Specials EXTREME CHEAPSKATES: VACATIONS – Wednesday, November 19 Season Finales BREAKING AMISH – Thursday, November 20 TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 18 9:00PM ET/PT 19 KIDS & COUNTING – “A REVEAL TO REMEMBER” The DC Duggars make it to Chicago in the nick of time for David and Priscilla’s gender reveal party! Then, the families are pushed to their limits during a day in the city. Anna faces her fear of heights 103 stories up, and everyone tests their waistlines when they make their own deep-dish pizzas. Later, they’re off on a fishing and camping excursion, where Josh and David attempt to catch a meal. And when Anna takes a pregnancy test, will she and Josh be in for a surprise of their own? 10:00PM ET/PT RISKING IT ALL – “WHAT THE FRONTIER” Join three families, the Elliotts, Kemps and Watfords, as they each unplug from technology and leave all modern-day conveniences behind to embark on new adventures and build new lives off the grid. WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 19 9:00PM ET/PT EXTREME CHEAPSKATES – “VACATIONS” This one-hour special profiles a group of penny-pinchers who want to hit the open road without breaking open their wallets. -

7 Am 7:30 8 Am 8:30 9 Am 9:30 10 Am 10:30 11 Am 11:30 12 Pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face the Nation (N) News International Swimming League Naples

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 8/29/21 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face the Nation (N) News International Swimming League Naples. (N) Å Bull Riding 4 NBC Today in LA Weekend Meet the Press (N) Å Tokyo Paralympics PGA Spec PGA Tour Golf BMW Championship, Final Round. 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch David Home 7 ABC Eyewitness News 7AM This Week Ocean Sea Rescue Hearts of Free Ent. Paid Prog. Paid Prog. LLWS 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday Joel Osteen Jeremiah Joel Osteen Harvest Mike Webb Home AAA Danette Icons The World’s 1 1 FOX Mercy Jack Hibbs Fox News Sunday The Issue News Emeril Pasta Secret Accident? Forgetful AAA PiYo 1 3 MyNet Bel Air Presbyterian Fred Jordan Freethought In Touch Jack Hibbs Paid Prog. Sex Abuse PiYo News The Issue 1 8 KSCI Fashion for Real Life OSO Casuals Fashions COVID Delta Safety: Dr. Cevherun Stefano Oro Stefano Oro 2 2 KWHY Programa Investing MagBlue Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Revitaliza Programa Programa Programa 2 4 KVCR Paint Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Marias Project Fire Simply Ming Milk Street How She 2 8 KCET Darwin’s A. Cat in the SciGirls Odd Squad Cyberchase Biz Kid$ Rick Steves Rick Steves Rick Steves’ Europe Eat Your Medicine 3 0 ION NCIS: New Orleans Å NCIS: New Orleans Å Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) 3 4 KMEX Programa Programa Programa Programa Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República deportiva (N) 4 0 KTBN R.