University Microfilms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COMMUNICATIONS WORLD/Spring-Summer 1977 } New Products

SPRING SUMMER 1977 $1.35 02003 EN :ommunicationsMN INCLUDING THE COMPLETE NIa Ett RLD AM FM TV SHORTWAVE wigip .7.-"FtEC . AUIO CO 1,1C National Radio Company HRO-600 communications receiver Where and When to - Hear Overseas English Language Broadcasts :test Bands for Around the Clock Listening Eavesdropping on the Utilities Joining a Radio Club Plus- How to Buy a SW Receiver How to pile up a QSL card collection L, How to tune in the police, fire fighters, aeronautical, national weather service, ship-to-shore, radio paging ysterns and more ! By the Editors of ELEMENTARY ELECTRONICS sr r _r_r_é.rc7rr itJA Jr.f!rAgMIOJ1zlÇfqalHnaW1ilAM 1IRT 11.Atiti 4;pw` "4Og5/OE .i q}+'TO }vOiÿ Y1Q q -.717 ßq7` 1.4 CIE's FCC LICENSE WARRANTY OF SUCCESS CIE warrants that when you enroll in any CIE course which includes FCC License preparation, you will, upon successful completion of the course and the FCC License material, pass the Government FCC Examination for the License for which your course prepared you. If you do not pass the appro- priate FCC Examination, you will be entitled to a full refund of an amount 4 equal to the cash price for CIE's "First Class FCC License Course," No. 3. This warranty will remain in effect from the date of your enrollment o1 to 90 days after the expiration o of the completion time allowed for your course. <. x® ¡xJ 7É7` qt-rV) C/-v\.) C \ )C2u\)C/ m cak.) C /rtyArc4=-J CIE's Warranty says a lot to you! A lot about CIE's FCC License training program, designed by experts to give you the best in Electronics programs...and a lot more about our school. -

Attachment I-Radio Stations in the Atlanta Urbanized Area

Before the I'lf\r\vr- FlECl::':.Ju.. ''t::'!' :--"""1;.1 FJ '" v ~j Federal Co~munications commlsslbiCOPYORJG'~" 0 Washington, D.C. 20554 1 ;,) 7998 ~~ OFFICE OF J'lH.. news COAf..~,,,,,. 'nc &:ClffTARY'~ In the Matter of ) ) Amendment ofSection 73.202(b), ) MM Docket No. 98-112 Table ofAllotments, FM Broadcast Stations ) RM-9027 (Anniston and Ashland, AL, College Park, ) RM-9268 Covington, and Milledgeville, Georgia) ) To: Chief, Allocations Branch REPLY COMMENTS Preston W. Small (Small), by his attorney, hereby replies to the various comments filed in the captioned docket. In reply thereto, the following is respectfully submitted: 1) WNNX's rule making petition seeks to remove existing service from 658,920 persons. WNNX's Technical Exhibit, Petition for Rule Making, p. 10. Paragraph 11 of the Notice of Proposed Rule Making ~RM) requires WNNX to "show what areas and populations will be separately served by the allotment ofChannel 261 C3 at Anniston and Channel 264A at Ashland . .." It is not apparent that WNNX's Comments respond to the Commission's inquiry. Figure 3 of WNNX's Comments, nominally titled, in part, "the Areas and Populations which will be separately served by Channel 261C3 at Anniston and 264A at Ashland," appears calculated to be responsive, however, WNNX's response presents combined, not separate, area and population figures for the two proposed fill-in stations. WNNX states that total service loss will be 658,920. However, WNNX's Figure 3 is not at all clear as to what is being counted. Figure 3 does not explicitly state ,., •.. :..•"-_.", .•._-~-,-,, ,,~,_._-- that the proposed Anniston and Ashland stations are excluded, Figure 3 does not provide separate data for service loss in the area to be served by the proposed stations, and Figure 3 does not contain separate service figures for the two proposed stations such that it is possible to determine how many people in the loss area each station would cover. -

Hadiotv EXPERIMENTER AUGUST -SEPTEMBER 75C

DXer's DREAM THAT ALMOST WAS SHASILAND HadioTV EXPERIMENTER AUGUST -SEPTEMBER 75c BUILD COLD QuA BREE ... a 2-FET metal moocher to end the gold drain and De Gaulle! PIUS Socket -2 -Me CB Skyhook No -Parts Slave Flash Patrol PA System IC Big Voice www.americanradiohistory.com EICO Makes It Possible Uncompromising engineering-for value does it! You save up to 50% with Eico Kits and Wired Equipment. (%1 eft ale( 7.111 e, si. a er. ortinastereo Engineering excellence, 100% capability, striking esthetics, the industry's only TOTAL PERFORMANCE STEREO at lowest cost. A Silicon Solid -State 70 -Watt Stereo Amplifier for $99.95 kit, $139.95 wired, including cabinet. Cortina 3070. A Solid -State FM Stereo Tuner for $99.95 kit. $139.95 wired, including cabinet. Cortina 3200. A 70 -Watt Solid -State FM Stereo Receiver for $169.95 kit, $259.95 wired, including cabinet. Cortina 3570. The newest excitement in kits. 100% solid-state and professional. Fun to build and use. Expandable, interconnectable. Great as "jiffy" projects and as introductions to electronics. No technical experience needed. Finest parts, pre -drilled etched printed circuit boards, step-by-step instructions. EICOGRAFT.4- Electronic Siren $4.95, Burglar Alarm $6.95, Fire Alarm $6.95, Intercom $3.95, Audio Power Amplifier $4.95, Metronome $3.95, Tremolo $8.95, Light Flasher $3.95, Electronic "Mystifier" $4.95, Photo Cell Nite Lite $4.95, Power Supply $7.95, Code Oscillator $2.50, «6 FM Wireless Mike $9.95, AM Wireless Mike $9.95, Electronic VOX $7.95, FM Radio $9.95, - AM Radio $7.95, Electronic Bongos $7.95. -

TV Channel 5-6 Radio Proposal

Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Promoting Diversification of Ownership ) MB Docket No 07-294 in the Broadcasting Services ) ) 2006 Quadrennial Regulatory Review – Review of ) MB Docket No. 06-121 the Commission’s Broadcast Ownership Rules and ) Other Rules Adopted Pursuant to Section 202 of ) the Telecommunications Act of 1996 ) ) 2002 Biennial Regulatory Review – Review of ) MB Docket No. 02-277 the Commission’s Broadcast Ownership Rules and ) Other Rules Adopted Pursuant to Section 202 of ) the Telecommunications Act of 1996 ) ) Cross-Ownership of Broadcast Stations and ) MM Docket No. 01-235 Newspapers ) ) Rules and Policies Concerning Multiple Ownership ) MM Docket No. 01-317 of Radio Broadcast Stations in Local Markets ) ) Definition of Radio Markets ) MM Docket No. 00-244 ) Ways to Further Section 257 Mandate and To Build ) MB Docket No. 04-228 on Earlier Studies ) To: Office of the Secretary Attention: The Commission BROADCAST MAXIMIZATION COMMITTEE John J. Mullaney Mark Lipp Paul H. Reynolds Bert Goldman Joseph Davis, P.E. Clarence Beverage Laura Mizrahi Lee Reynolds Alex Welsh SUMMARY The Broadcast Maximization Committee (“BMC”), composed of primarily of several consulting engineers and other representatives of the broadcast industry, offers a comprehensive proposal for the use of Channels 5 and 6 in response to the Commission’s solicitation of such plans. BMC proposes to (1) relocate the LPFM service to a portion of this spectrum space; (2) expand the NCE service into the adjacent portion of this band; and (3) provide for the conversion and migration of all AM stations into the remaining portion of the band over an extended period of time and with digital transmissions only. -

BROADCAST MAXIMIZATION COMMITTEE John J. Mullaney

Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Promoting Diversification of Ownership ) MB Docket No 07-294 in the Broadcasting Services ) ) 2006 Quadrennial Regulatory Review – Review of ) MB Docket No. 06-121 the Commission’s Broadcast Ownership Rules and ) Other Rules Adopted Pursuant to Section 202 of ) the Telecommunications Act of 1996 ) ) 2002 Biennial Regulatory Review – Review of ) MB Docket No. 02-277 the Commission’s Broadcast Ownership Rules and ) Other Rules Adopted Pursuant to Section 202 of ) the Telecommunications Act of 1996 ) ) Cross-Ownership of Broadcast Stations and ) MM Docket No. 01-235 Newspapers ) ) Rules and Policies Concerning Multiple Ownership ) MM Docket No. 01-317 of Radio Broadcast Stations in Local Markets ) ) Definition of Radio Markets ) MM Docket No. 00-244 ) Ways to Further Section 257 Mandate and To Build ) MB Docket No. 04-228 on Earlier Studies ) To: Office of the Secretary Attention: The Commission BROADCAST MAXIMIZATION COMMITTEE John J. Mullaney Mark Lipp Paul H. Reynolds Bert Goldman Joseph Davis, P.E. Clarence Beverage Laura Mizrahi Lee Reynolds Alex Welsh SUMMARY The Broadcast Maximization Committee (“BMC”), composed of primarily of several consulting engineers and other representatives of the broadcast industry, offers a comprehensive proposal for the use of Channels 5 and 6 in response to the Commission’s solicitation of such plans. BMC proposes to (1) relocate the LPFM service to a portion of this spectrum space; (2) expand the NCE service into the adjacent portion of this band; and (3) provide for the conversion and migration of all AM stations into the remaining portion of the band over an extended period of time and with digital transmissions only. -

201-300-Radio-Annual

GEORGIA Owned By Coffee County Bcstrs. Owned-Operated By Rocket Radio, Inc. Box 471 Tel.: 384-1239 Address Roberta Road Independent Rep.: Beaver Tel.: TA 5-5547 KBS Pres., Gen. Mgr. Joe Trankina General Mqr. Paul Reehling Chief Engineer. Joe Stephens WMLT Dublin 1945 Frequency: 1330 Kc. Power: 5 Kw. WBUH Gainesville 1949 Owned-Operated By Dublin Bdcstq. Co. Freq.: 1240 Kc..... Power: 1000 Watts d. 250 n. Business & Moore Sts. Address Franklin Owned-Oper. By N.E. Ga. Bcstg. Co. Tel.: BR 2-4422 KBS Address 1102 Thompson Bridge Rd., N.E. President W. Newton Morris Tel.: 534-7331 ABC General Frank Mqr Floyd Jr. Rep. Thomas F. Clark; Dora-Clayton R Sales Prom. Mgr. E. Hilliard Pres., Gen. Manager John W. Jacobs, Jr. Leon Chief Engineer Lloyd Station Mgr. James N. Martin, Jr. Comm. Mgr. Claire T. Palmour WXLI Dublin 1958 Program Director Jim Martin Sales Prom. Mgr. Robert S. Culler Freq.: 1230 Kc..... Power: 1 Kw. d., 250 W. n. Chief R. Wilkes Owned Laurens Co. Engineer George By County Bcstg. lhviker, of: WDU -h31. Address P O Box 967 Tel.: Broad 2-4282 Independent President, Gen. Mgr. Ted Kirby WGGA Gainesville 1941 Station Jessie Manager Hagler Frequency: 550 Kc.. Power: 5 Kw. d.; 500 W. n. Director Bill Thomas Program Owned By Southern Bcstg. Co. Publicity Director Frances Lord Business Address Press-Radio Center Tel.: LE 2-6211 CBS WTJH East Point 1949 President, Gen. Mgr. A R. MacMillan Operations Manager James Frequency: 1260 Kc..... Power: 5000 Watts d. Hartley Chief Engineer Wilbert Darracott Owned By Southeastern Bcstg. -

Freq Call State Location U D N C Distance Bearing

AM BAND RADIO STATIONS COMPILED FROM FCC CDBS DATABASE AS OF FEB 6, 2012 POWER FREQ CALL STATE LOCATION UDNCDISTANCE BEARING NOTES 540 WASG AL DAPHNE 2500 18 1107 103 540 KRXA CA CARMEL VALLEY 10000 500 848 278 540 KVIP CA REDDING 2500 14 923 295 540 WFLF FL PINE HILLS 50000 46000 1523 102 540 WDAK GA COLUMBUS 4000 37 1241 94 540 KWMT IA FORT DODGE 5000 170 790 51 540 KMLB LA MONROE 5000 1000 838 101 540 WGOP MD POCOMOKE CITY 500 243 1694 75 540 WXYG MN SAUK RAPIDS 250 250 922 39 540 WETC NC WENDELL-ZEBULON 4000 500 1554 81 540 KNMX NM LAS VEGAS 5000 19 67 109 540 WLIE NY ISLIP 2500 219 1812 69 540 WWCS PA CANONSBURG 5000 500 1446 70 540 WYNN SC FLORENCE 250 165 1497 86 540 WKFN TN CLARKSVILLE 4000 54 1056 81 540 KDFT TX FERRIS 1000 248 602 110 540 KYAH UT DELTA 1000 13 415 306 540 WGTH VA RICHLANDS 1000 97 1360 79 540 WAUK WI JACKSON 400 400 1090 56 550 KTZN AK ANCHORAGE 3099 5000 2565 326 550 KFYI AZ PHOENIX 5000 1000 366 243 550 KUZZ CA BAKERSFIELD 5000 5000 709 270 550 KLLV CO BREEN 1799 132 312 550 KRAI CO CRAIG 5000 500 327 348 550 WAYR FL ORANGE PARK 5000 64 1471 98 550 WDUN GA GAINESVILLE 10000 2500 1273 88 550 KMVI HI WAILUKU 5000 3181 265 550 KFRM KS SALINA 5000 109 531 60 550 KTRS MO ST. LOUIS 5000 5000 907 73 550 KBOW MT BUTTE 5000 1000 767 336 550 WIOZ NC PINEHURST 1000 259 1504 84 550 WAME NC STATESVILLE 500 52 1420 82 550 KFYR ND BISMARCK 5000 5000 812 19 550 WGR NY BUFFALO 5000 5000 1533 63 550 WKRC OH CINCINNATI 5000 1000 1214 73 550 KOAC OR CORVALLIS 5000 5000 1071 309 550 WPAB PR PONCE 5000 5000 2712 106 550 WBZS RI -

PUBLIC VERSION Before the COPYRIGHT ROYALTY JUDGES

PUBLIC VERSION Before the COPYRIGHT ROYALTY JUDGES LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Washington, D.C. ) IN THE MATTER OF: ) ) ) Docket No. 2005-1 CRB DTRA DIGITAL PERFORMANCE RIGHT . ) IN SOUND RECORDINGS AND . ) EPHEMERAL RECORDINGS ) ) RADIO FINDINGS OFBROADCASTERS'ROPOSED FACT AND CONCLUSIONS OF LAW Bruce G. Joseph (D.C. Bar No. 338236) Karyn K. Ablin (D.C. Bar No. 454473) Matthew J. Astle (D.C. Bar No. 488084) WILEY REIN 4 FIELDING LLP 1776 K Street NW Washington, DC 20006 202.719.7258 202.719.7049 (Fax) [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Counselfor Bonneville International Corp., Clear Channel Communications Inc.; Nationa/ Religious Broadcasters Music License Committee, and Susquehanna Radio Corp. December 15, 2006 PUBLIC VERSION Before the COPYRIGHT ROYALTY JUDGES LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Washington, D.C. Qa IN THE MATTER OF: S~ Docket No. 2005-1 CRB DTRA DIGITAL PERFORMANCE RIGHT +a IN SOUND RECORDINGS AND EPHEMERAL RECORDINGS (oO RADIO FINDINGS OFBROADCASTERS'ROPOSED FACT AND CONCLUSIONS OF LAW Bruce G. Joseph (D.C. Bar No. 338236) Karyn K. Ablin (D.C. Bar No. 454473) Matthew J. Astle (D.C. Bar No. 488084) WILEY REIN 8'c FIELDING LLP 1776 K Street NW Washington, DC 20006 202.719.7258 202.719.7049 (Fax) bjosephlwrf.corn [email protected] [email protected] Counselfor Bonneville International Corp., Clear Channel Communications, Inc.; National Religious Broadcasters Music License Committee, and Susquehanna Radio Corp. December 15, 2006 PUBLIC VERSION TABLE OF CONTENTS P~ae PROPOSED FINDINGS OF FACT. I. INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW. II. RADIO BROADCASTERS AND AM/FM STREAMING. III. HISTORY OF RADIO'S RELATIONSHIP WITH THE SOUND RECORDING PERFORMANCE RIGHT A. -

The Private Agreement and Citizen Participation in Broadcast Regulation. PUB DATE 72 NOTE 120P.; M.A

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 079 784 cs 500 350 AUTHOR Fry, Carlton Ford' TITLE The Private Agreement and Citizen Participation in Broadcast Regulation. PUB DATE 72 NOTE 120p.; M.A. Thesis, Ohio State University EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$6.58 DESCRIPTORS Broadcast Industry; Broadcast Illevision; *Citizen Participation; *Commercial Television; Community Organizations; Court Litigation; *Legal Responsibility; *Programing (Broadcast); *Public Affairs Education; Public Television; Telecommunication IDENTIFIERS Broadcaster Licenses; *Federal Communicatiops Commission; Office of Communication (Federal) ABSTRACT The kind and extent of public access and control in broadcast commercial television is currently in a state of extreme flux. The history of public groups that exert pressure on television stations, management for changes in programing and policies ranges from small complaints to fully organized license challenges in the courts. However, most of the conflicts between broadcasters and public interest forces are settled privately--out of court. The effect of such private negotiation is not always in the interests of the whole public. Placation of one grievance rather than iasic improvement is sometimes the result..Solution tp this situation likely lies with the Federal Communications Commission. .(CH) FILMED FROM BEST AVAILABLE COPY US DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH EDUCATION L WELFAR:. NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED I.ROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATIGN ORIGIN .TING IT POINTS Or viEN OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRE SENT OFFICIAL NPONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY THE PRIVATE AGREEMENT AND CITIZEN PARTICIPATION IN BROADCAST REGULATION A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts By "PERMISSION TO REPRODUCETHIS COPY. -

DOC-309139A1.Pdf

FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION FACT SHEET FY 2011 AM & FM RADIO STATION REGULATORY FEES Class of Fac. Id. Call Sign Licensee Name Service 84272 961115MD NORTHERN LIGHTS BROADCASTING, L.L.C. FM 87880 970724NE PAMPA BROADCASTERS INC FM 88463 970925MP KRJ COMPANY FM 89133 971022MC GEORGE S. FLINN, JR. FM 160321 DKACE INTERMOUNTAIN MEDIA, LLC AM 164193 DKAHA SOUTH TEXAS FM INVESTMENTS, LLC FM 164213 DKANM TANGO RADIO, LLC FM 166076 DKBWT MAGNOLIA RADIO CORPORATION FM 83886 DKCHC PACIFIC SPANISH NETWORK, INC. FM 33725 DKCLA M.R.S. VENTURES, INC. AM 161165 DKDAN INTERMOUNTAIN MEDIA, LLC AM 129546 DKEWA KM COMMUNICATIONS, INC. AM 170947 DKGQQ KEMP COMMUNICATIONS, INC. FM 165974 DKHES INNOVATED FACILITY SOLUTIONS, INC. FM 160322 DKIFO INTERMOUNTAIN MEDIA, LLC AM 170990 DKIXC NOALMARK BROADCASTING CORPORATION FM 164216 DKKUL-FM TANGO RADIO, LLC FM 164214 DKNOS TANGO RADIO, LLC FM 4236 DKOTN M.R.S. VENTURES, INC. AM 52619 DKPBQ-FM M.R.S. VENTURES, INC. FM 86857 DKRKD M.R.S. VENTURES, INC. FM 170967 DKRKP JER LICENSES, LLC FM 164191 DKTSX SOUTH TEXAS FM INVESTMENTS, LLC FM 70630 DKTTL W.H.A.M. FOR BETTER BROADCASTING, INC. FM 164197 DKXME SOUTH TEXAS FM INVESTMENTS, LLC FM 33726 DKZYP M.R.S. VENTURES, INC. FM 16551 DKZYQ M.R.S. VENTURES, INC. FM 160230 DNONE NORTH STAR BROADCASTING PARTNERS, LLC AM 160392 DNONE TONOPAH RADIO, LLC AM 48759 DWCMA PERIHELION GLOBAL, INC. AM 2297 DWCRW NATIONS RADIO, LLC AM 46952 DWCUG MULLIS COMMUNICATIONS, INC. AM 160767 DWDME WIRELESS FIDELITY OF NORTH AMERICA, INC. AM 71349 DWDOD WDOD OF CHATTANOOGA, INC. -

Strikers Wounded Minneapolis Riot

.' . ji. X AVBBAOB DAILT CIBCXDATION fovvtiM Month ot Jnna i m _ THE WEATHER ■ Forwian Of tj. 8 Waathw 5,428 Baittord Member of tho AnMt Bwonu of Utrenlnttons. OenerMlj lUr tonight and 8nn- “ }’; not nrarh change la tempera- tore* .VOL. U n ., NO. 248. (LTnssUled Advertising on Pngo MANCHESTER, CONN., SATURDAY, JULY 21,1934. (TEN PAGES) PRICE THREE CENTS 4>- TO USE ALUOATORS 1 IS A.MAZON VENTURE i 10; POST OFFICE IS Army Planes Off To “Protect” Alaska Para, Brazil, July 21.—(AP)— Braall hopea to get some money OUT OF THE RED out of its millions of alligators. Count Penteado, Sao Paulo In- STRIKERS WOUNDED dustriiUlst, plans to establish a X.' FARLM ATES factory, here to extract alligator oU and cure hides for export. The oU, he believes, would make a good substitute for whale oil. The .Island of Marajo, In the MINNEAPOLIS RIOT Income Exceeds Expenses mouth of the Amazon, ^^11 be an abundant source of initlM supply, by $5,000; First Year with the whole Amazon system Thredt of General Walkout ,^to draw on If the industry b^m s. track f risco Is Almost Back Without Deficit Since Grips City-T-Coast Strike 1 9 1 9 ,7th in Half Century To Normal Conditions Spreads to Portland, Ore- FIVE CCC WORKERS Washington, July 21.—Postmaa San Francisco, July 21.—(AP) — , gon — Tear Gas Routs the day moss walkout which officially ! Iw General Farley has Informed THOUGHT DROWNED Hopes of peace stirred anew along ended Thursday. At Los Angeles ' President Roosevelt that a long- the strike tom Pacific coa.st today_ HuRh Johnson, NRA administrator, 2,000 Workers on Seat- . -

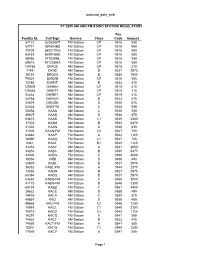

Postcard Data Web Fee Facility Id. Call Sign Service Class Code

postcard_data_web FY 2005 AM AND FM RADIO STATION REGULATORY Fee Facility Id. Call Sign Service Class Code Amount 57172 820520AT FM Station CP 0516 550 57771 820524BD FM Station CP 0516 550 70709 880217NG FM Station CP 0516 550 83423 960916ME FM Station CP 0516 550 89056 971030ML FM Station CP 0516 550 89615 971226MA FM Station CP 0516 550 129788 DKACE AM Station CP 0515 310 7749 DKIIS AM Station B 0527 2975 36167 DKQXX AM Station B 0526 1950 79024 DKRZB FM Station CP 0516 550 72785 DWBIT AM Station B 0523 475 129309 DWKKK AM Station CP 0515 310 129354 DWKTT AM Station CP 0515 310 54464 DWREY AM Station CP 0515 310 54768 DWVUV AM Station B 0523 475 25819 DWVZN AM Station D 0536 675 54328 DWWTM AM Station C 0530 550 55492 KAAA AM Station C 0530 550 39607 KAAB AM Station D 0536 675 63872 KAAK FM Station C1 0549 2300 17303 KAAM AM Station B 0580 5475 31004 KAAN AM Station D 0535 450 31005 KAAN-FM FM Station C2 0547 725 63882 KAAP FM Station A 0542 1125 18090 KAAQ FM Station C1 0547 725 8341 KAAT FM Station B1 0542 1125 33253 KAAY AM Station A 0521 3950 33254 KABC AM Station B 0580 5475 44000 KABG FM Station C 0550 3000 18054 KABI AM Station D 0535 450 26925 KABL AM Station B 0527 2975 36032 KABL-FM FM Station A 0544 2375 13550 KABN AM Station B 0527 2975 65394 KABQ AM Station B 0527 2975 53652 KABQ-FM FM Station C 0550 3000 41173 KABX-FM FM Station B 0549 2300 60134 KABZ FM Station C 0551 4400 29622 KACE AM Station D 0535 450 74476 KACH AM Station C 0529 375 49857 KACI AM Station D 0535 450 49856 KACI-FM FM Station C2 0548 1250 15967 KACL