BEAVER CREEK MOUNTAIN IMPROVEMENTS PROJECT DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT November 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

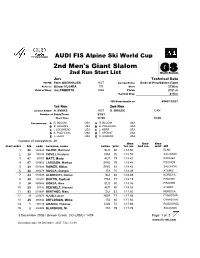

R Startlist 2Manche

AUDI FIS Alpine Ski World Cup 2nd Men's Giant Slalom 2nd Run Start List GiantGS Slalom Jury Technical Data TD FIS Peter OBERNAUER AUT Course Name Birds of Prey/Golden Eagle Referee Günter HUJARA FIS Start 3136 m Chief of Race Jim ROBERTS USA Finish 2721 m Vertical Drop 415 m FIS Homologatio nr 4945/128/97 1st Run 2nd Run Course Setter A. EVERS AUT D. GRASIC CAN Number of Gates/Turns 53/51 Start Time 11:00 14:00 Forerunners A R. BLOOM USA A R. BLOOM USA B S. HIGGINS USA B B. POEHLING USA C I. LOCHHEAD USA C J. HERR USA D B. POEHLING USA D T. SPENST USA E J. HERR USA E S. HIGGINS USA Number of competitors: 30 time time time start order bib code surname, name nation year 1st run 2nd run total ski 1 58 560425 VAJDIC, Bernard SLO 80 1:18.60 ELAN 2 28 190236 COVILI, Frederic FRA 75 1:18.55 SALOMON 3 47 50707 MATT, Mario AUT 79 1:18.47 FISCHER 4 67 500656 LARSSON, Markus SWE 79 1:18.44 FISCHER 5 29 501026 RAINER, Niklas SWE 83 1:18.42 SALOMON 6 34 290478 ROCCA, Giorgio ITA 75 1:18.39 ATOMIC 7 44 510993 ALBRECHT, Daniel SUI 83 1:18.39 NORDICA 8 49 191227 BURTIN, Raphael FRA 77 1:18.15 FISCHER 9 24 560406 GORZA, Ales SLO 80 1:18.05 FISCHER 10 39 50742 REICHELT, Hannes AUT 80 1:18.03 ATOMIC 11 42 510997 BERTHOD, Marc SUI 83 1:17.92 NORDICA 12 9 420470 KJUS, Lasse NOR 71 1:17.85 DYNASTAR 13 25 290844 DEFLORIAN, Mirko ITA 80 1:17.84 DYNASTAR 14 1 100115 GRANDI, Thomas CAN 72 1:17.83 ROSSIGNOL 15 2 292000 BLARDONE, M. -

Ranking 2018 Po Zaliczeniu 120 Dyscyplin

RANKING 2018 PO ZALICZENIU 120 DYSCYPLIN OCENA PKT. ZŁ. SR. BR. SPORTS BEST 1. Rosja 238.5 1408 219 172 187 72 16 2. USA 221.5 1140 163 167 154 70 18 3. Niemcy 185.0 943 140 121 140 67 7 4. Francja 144.0 736 101 107 118 66 4 5. Włochy 141.0 701 98 96 115 63 8 6. Polska 113.5 583 76 91 97 50 8 7. Chiny 108.0 693 111 91 67 35 6 8. Czechy 98.5 570 88 76 66 43 7 9. Kanada 92.5 442 61 60 78 45 5 10. Wielka Brytania / Anglia 88.5 412 51 61 86 49 1 11. Japonia 87.5 426 59 68 54 38 3 12. Szwecja 84.5 367 53 53 49 39 3 13. Ukraina 84.0 455 61 65 81 43 1 14. Australia 73.5 351 50 52 47 42 3 15. Norwegia 72.5 451 66 63 60 31 2 16. Korea Płd. 68.0 390 55 59 52 24 3 17. Holandia 68.0 374 50 57 60 28 3 18. Austria 64.5 318 51 34 46 38 4 19. Szwajcaria 61.0 288 41 40 44 33 1 20. Hiszpania 57.5 238 31 34 46 43 1 21. Węgry 53.0 244 35 37 30 27 3 22. Nowa Zelandia 42.5 207 27 35 29 25 2 23. Brazylia 42.0 174 27 20 26 25 4 24. Finlandia 42.0 172 23 23 34 33 1 25. Białoruś 36.0 187 24 31 29 22 26. -

Constance, GER, November 2019

To the INTERNATIONAL SKI FEDERATION - Members of the FIS Council Blochstrasse 2 - National Ski Associations 3653 Oberhofen/Thunersee - Committee Chairs Switzerland Tel +41 33 244 61 61 Fax +41 33 244 61 71 Oberhofen, 26th November 2019 Summary of the FIS Council Meeting, 23rd November 2019, Konstanz / Constance (GER) Dear President, Dear Ski Friends, In accordance with art. 32.2 of the FIS Statutes we have pleasure in sending you the Summary of the most important decisions from the FIS Council Meeting which took place on 23rd November 2019 in Constance (GER). 1. Members present The following elected Council Members were present at the meeting in Constance (GER) on Saturday, 23rd November 2019: President Gian Franco Kasper, Vice-Presidents Mats Arjes, Janez Kocijancic and Aki Murasato, Members: Steve Dong Yang, Dean Gosper, Alfons Hörmann, Hannah Kearney (Athletes’ Commission Representative), Roman Kumpost, Dexter Paine, Flavio Roda, Erik Roeste, Konstantin Schad (Athletes’ Commission Representative), Peter Schröcksnadel, Martti Uusitalo, Eduardo Valenzuela and Michel Vion, Secretary General Sarah Lewis Apologies: Vice-President Patrick Smith, Council Member Andrey Bokarev Honorary Members: Sverre Seeberg, Carl-Eric Stalberg, Hank Tauber Guest: Franz Steinle President German Ski Association Observer: Dave Pym (CAN) representing Patrick Smith Experts: Stephan Netzle, Legal Counsel; Erwin Lauterwasser, Environment 2. Minutes from the Council Meeting in Cavtat-Dubrovnik (CRO) June 2019 The Summary and Minutes from the Council Meetings in -

86Th International Lauberhorn Races Wengen

86th International Lauberhorn Races Wengen General information The races are organized by the «Verein Internationale Lauberhornrennen Wengen» in accordance with the regulation of the FIS rules as part of the Audi Ski World Cup. Registration Eligible are only the ski racers who have been enroled by a national FIS association. The number of participants is limited and it bases on the FIS rules of the Ski World Cup Committee. Race entries The registration takes place according to FIS regulations online only via www.fis-ski.com . Subject to art. 4.5 (Rules for the FIS Alpine Ski World Cup) the entry must be sent by Wednesday, January 6, 2016, 12 noon at the latest . On arrival in Wengen teams must immediately report to the Race Office (Tourist Center Wengen). Official notice boards All official informations, startlists and official results will be displayed near the entrance of the Race Office. Protests All protests must be filed within the allowed time given by the FIS rules or the jury. Prize money and payment of travel expenses According to art. 5.4 and 6 (Rules for the FIS Alpine Ski World Cup) the payment of the prize money and the travel expenses will only be paid electronically by bank transfer. The FIS has uploaded a form on the website. The Team Captain is responsible for the correct handling and in charge to report the details to the Race Office. Parking Free parking including free shuttle service during the Ski World Cup is available at the Teamparking «Eyelti» in Lauterbrunnen. Address Verein Internationale Lauberhornrennen P.O. -

FIS Style Guide

FIS STYLEGUIDE (last updated March 2020) 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents …………………………………………………………………………………………. 1 Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………………. 2 General notes………………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Preferred terminology……………………………………………………………………………………… 4 Other related FIS terminology……………………………………………………………………………. 4 Names and titles…………………………………………………………………………………………… 5 FIS Olympic disciplines……………………………………………………………………………………. 6 FIS non-Olympic disciplines………………………………………………………………………………. 6 Olympic Games…………………………………………………………………………………………….. 7 World Ski Championships (WSC) ……………………………………………………………………….. 8 Junior World Ski Championships (JWSC) ……………………………………………………………… 9 World Cup…………………………………………………………………………………………………... 9 FIS World Cup with sponsors ………..………………………………………………………………….. 10 Other events………………………………………………………………………………………………... 11 Events and styles………………………………………………………………………………………….. 12 Dates and numbers………………………………………………………………………………………... 14 Units of measurement……………………………………………………………………………………... 14 Time…………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 15 Miscellaneous……………………………………………………………………………………………… 15 Use of hyphen……………………………………………………………………………………………… 15 Country names and codes………………………………………………………………………………... 16 Commonly used acronyms……………………………………………………………………………….. 20 Additional FIS terminology………………………………………………………………………………... 21 FIS Committees……………………………………………………………………………………………. 24 Coordination Group for Snowboard and Freestyle…………………………………………………...... 25 Special Committees……………………………………………………………………………………….. 25 -

FIS Alpine Ski World Cup, Yanqing (CHN) Cancelled

INTERNATIONAL SKI FEDERATION Blochstrasse 2 3653 Oberhofen/Thunersee Switzerland FOR MORE INFORMATION Jenny Wiedeke FIS Communications Director Mobile: + 41 79 449 5399 E-Mail: [email protected] Oberhofen, Switzerland 29.1.2020 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE FIS MEDIA INFO FIS Alpine Ski World Cup, Yanqing (CHN) Cancelled Due to the outbreak and continuing spread of the Novel Coronavirus, FIS, the Chinese Ski Association and its Yanqing Local Organising Committee, have jointly decided to cancel the upcoming men’s Audi FIS World Cup races scheduled for 15 th -16 th February 2020. “It is with great regret that all of the stakeholders are obliged to take the difficult decision to cancel the World Cup races in Yanqing this season, as the historic first FIS Alpine Ski World Cup in China and the first official Beijing 2022 Test Event,” said FIS President Gian Franco Kasper. “Although the risk level in Yanqing is low, the health and welfare of the athletes and all participants must take priority. It is also imperative that athletes can focus on their performance and particularly on the completely new and very challenging course. The first competitions on the new Olympic downhill course in Yanqing were carried out successfully as part of the 14th Chinese National Winter Games from 16 th to 20 th January. The FIS Technical Experts and Medical Supervisor who were present were very pleased with the new course and snow conditions, as well as the organisation of the event and mountain operations. FIS will advise at a later date in regard to the rescheduling of the cancelled races from Yanqing: a downhill and a super-G. -

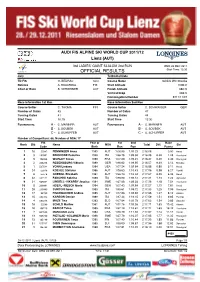

OFFICIAL RESULTS Start Time: 13:30 Jury Technical Data TD FIS G

AUDI FIS ALPINE SKI WORLD CUP 2011/12 Lienz (AUT) 3rd LADIES’ GIANT SLALOM 2nd RUN WED 28 DEC 2011 OFFICIAL RESULTS Start Time: 13:30 Jury Technical Data TD FIS G. BEDRAC SLO Course Name Schlick WC Strecke Referee A. SKAARDAL FIS Start Altitude 1008 m Chief of Race S. VERGEINER AUT Finish Altitude 680 m Vertical Drop 328 m Homologation Number 8711/11/07 Race Information 1st Run Race Information 2nd Run Course Setter C. THOMA FIN Course Setter C. SCHWAIGER GER Number of Gates 43 Number of Gates 47 Turning Gates 41 Turning Gates 44 Start Time 10:15 Start Time 13:30 Forerunners A - C. MARINER AUT Forerunners A - C. MARINER AUT B - S. SOUBEK AUT B - S. SOUBEK AUT C - S. SCHUPFER AUT C - S. SCHUPFER AUT Number of Competitors: 66, Number of NSA: 17 FIS Year of 1st 2nd Race Rank Bib Name NSA Total Diff. Ski Code Birth Run Run Points 1 16 55947 FENNINGER Anna 1989 AUT 1:06.85 1:09.23 2:16.08 0.00 Head 2 3 297601 BRIGNONE Federica 1990 ITA 1:06.78 1:09.50 2:16.28 0.20 1.28 Rossignol 3 5 196928 WORLEY Tessa 1989 FRA 1:07.26 1:09.21 2:16.47 0.39 2.49 Rossignol 4 2 205218 REBENSBURG Viktoria 1989 GER 1:06.62 1:09.95 2:16.57 0.49 3.13 Nordica 5 1 537544 VONN Lindsey 1984 USA 1:07.24 1:09.64 2:16.88 0.80 5.11 Head 6 24 55818 KOEHLE Stefanie 1986 AUT 1:06.63 1:10.43 2:17.06 0.98 6.27 Voelkl 7 6 55576 GOERGL Elisabeth 1981 AUT 1:06.73 1:10.34 2:17.07 0.99 6.33 Head 8 42 297171 FANCHINI Sabrina 1988 ITA 1:08.09 1:09.12 2:17.21 1.13 7.22 Dynastar 9 21 505632 LINDELL−VIKARBY Jessica 1984 SWE 1:07.88 1:09.38 2:17.26 1.18 7.54 Rossignol 10 8 206001 HOEFL−RIESCH -

From Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Audi Type Private Company

Audi From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Audi Private company Type (FWB Xetra: NSU) Industry Automotive industry Zwickau, Germany (16 July Founded 1909)[1] Founder(s) August Horch Headquarters Ingolstadt, Germany Production locations: Germany: Ingolstadt & Neckarsulm Number of Hungary: Győr locations Belgium: Brussels China: Changchun India: Aurangabad Brazil: Curitiba Area served Worldwide Rupert Stadler Key people Chairman of the Board of Management, Wolfgang Egger Head of Design Products Automobiles, Engines Production 1,143,902 units (2010) output (only Audi brand) €35.441 billion (2010) Revenue (US$52.57 billion USD) (including subsidiaries) €1.850 billion (2009) Profit (US$2.74 billion USD) €16.832 billion (2009) Total assets (US$25 billion USD) €3.451 billion (2009) Total equity (US$5.12 billion USD) Employees 46,372 (2009)[2] Parent Volkswagen Group Audi do Brasil e Cia (Curitiba, Brazil) Audi Hungaria Motor Kft. (Györ, Hungary) Audi Senna Ltda. (Brazil) Automobili Lamborghini Subsidiaries Holding S.p.A (Sant'Agata Bolognese, Italy) Autogerma S.p.A. (Verona, Italy) quattro GmbH (Neckarsulm, Germany) Website audi.com Audi AG (Xetra: NSU) is a German automobile manufacturer, from supermini to crossover SUVs in various body styles and price ranges that are marketed under the Audi brand (German pronunciation: [ˈaʊdi]), positioned as the premium brand within the Volkswagen Group.[3] The company is headquartered in Ingolstadt, Germany, and has been a wholly owned (99.55%)[4] subsidiary of Volkswagen AG since 1966, following a phased purchase of its predecessor, Auto Union, from its former owner, Daimler-Benz. Volkswagen relaunched the Audi brand with the 1965 introduction of the Audi F103 series. -

OFFICIAL RESULTS Start Time: 11:00 Jury Technical Data TD FIS D

AUDI FIS ALPINE SKI WORLD CUP FINALS 2011/12 Schladming (AUT) 7th LADIES’ SUPER-G THU 15 MAR 2012 OFFICIAL RESULTS Start Time: 11:00 Jury Technical Data TD FIS D. MENESTRINA ITA Course Name Streicher Referee A. SKAARDAL FIS Start Altitude 1285 m Assistant Referee J. TISCHHAUSER FIS Finish Altitude 771 m Chief of Race M. STEINER AUT Vertical Drop 514 m Course Length 2226 m Homologation Number 10380/12/11 Race Information Course Setter J. WALLNER SWE Number of Gates 44 Turning Gates 38 Start Time 11:00 Forerunners A - S. AUER AUT C - D. JETZ AUT B - K. BRUNNER AUT D - A. KNAUSS AUT Number of Competitors: 26, Number of NSA: 11 F-factor: 1060 FIS Year of Race Rank Bib Name NSA TimeDiff. Dist. (m) Ski Code Birth Points 1 5 205218 REBENSBURG Viktoria 1989 GER 1:24.54 0.00 Nordica 2 16 537545 MANCUSO Julia 1984 USA 1:24.72 0.18 4.73 2.26 Voelkl 3 2 195983 ROLLAND Marion 1982 FRA 1:24.75 0.21 5.52 2.63 Rossignol 4 20 55947 FENNINGER Anna 1989 AUT 1:25.07 0.53 13.87 6.65 Head 5 6 538305 SMITH Leanne 1987 USA 1:25.09 0.55 14.39 6.90 Rossignol 6 17 537544 VONN Lindsey 1984 USA 1:25.11 0.57 14.91 7.15 Head 7 21 565243 MAZE Tina 1983 SLO 1:25.36 0.82 21.38 10.28 Stoeckli 8 4 505483 PAERSON Anja 1981 SWE 1:25.48 0.94 24.48 11.79 Head 9 14 297910 CURTONI Elena 1991 ITA 1:25.50 0.96 24.99 12.04 Atomic 10 22 355050 WEIRATHER Tina 1989 LIE 1:25.52 0.98 25.51 12.29 Atomic 11 15 55576 GOERGL Elisabeth 1981 AUT 1:25.58 1.04 27.05 13.04 Head 12 3 55913 MOSER Stefanie 1988 AUT 1:25.67 1.13 29.36 14.17 Fischer 13 18 516138 GUT Lara 1991 SUI 1:25.73 1.19 30.90 -

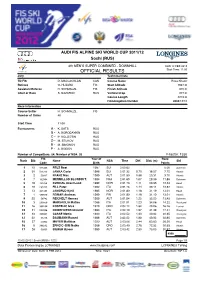

Official Results Speed Run for SC

AUDI FIS ALPINE SKI WORLD CUP 2011/12 Sochi (RUS) 4th MEN’S SUPER COMBINED - DOWNHILL SUN 12 FEB 2012 OFFICIAL RESULTS Start Time: 11:00 Jury Technical Data TD FIS D. MACLACHLAN CAN Course Name Rosa Khutor Referee G. HUJARA FIS Start Altitude 1947 m Assistant Referee H. SCHMALZL FIS Finish Altitude 970 m Chief of Race S. NAZAROV RUS Vertical Drop 977 m Course Length 3219 m Homologation Number 9888/12/10 Race Information Course Setter H. SCHMALZL FIS Number of Gates 40 Start Time 11:00 Forerunners A - K. SATS RUS B - A. BORODAYKIN RUS C - P. KOLGOTIN RUS D - M. STUKOV RUS E - M. SIMONOV RUS F - A. BOISOV RUS Number of Competitors: 54, Number of NSA: 20 F-factor: 1330 FIS Year of Race Rank Bib Name NSA TimeDiff. Dist. (m) Ski Code Birth Points 1 19 511383 FEUZ Beat 1987 SUI 2:00.62 0.00 Salomon 2 30 511313 JANKA Carlo 1986 SUI 2:01.32 0.70 18.57 7.72 Atomic 3 2 53817 FRANZ Max 1989 AUT 2:01.50 0.88 23.31 9.70 Atomic 4 7 192504 MERMILLOD BLONDIN T. 1984 FRA 2:01.69 1.07 28.30 11.80 Salomon 5 18 421328 SVINDAL Aksel Lund 1982 NOR 2:01.73 1.11 29.35 12.24 Head 6 10 292455 FILL Peter 1982 ITA 2:01.76 1.14 30.14 12.57 Atomic 7 13 421483 JANSRUD Kjetil 1985 NOR 2:01.80 1.18 31.19 13.01 Head 7 1 180570 ROMAR Andreas 1989 FIN 2:01.80 1.18 31.19 13.01 Atomic 9 25 50742 REICHELT Hannes 1980 AUT 2:01.84 1.22 32.23 13.45 Salomon 10 3 293550 MARSAGLIA Matteo 1985 ITA 2:01.91 1.29 34.06 14.22 Rossignol 11 16 380260 KOSTELIC Ivica 1979 CRO 2:02.14 1.52 40.06 16.76 Fischer 12 21 293006 INNERHOFER Christof 1984 ITA 2:02.19 1.57 41.36 17.31 Rossignol 13 -

How to Cover the FIS Alpine World Cup

How to Cover The FIS Alpine World Cup Thank you for your interest in the athletes and events of the Audi FIS Alpine Ski World Cup. We have a unique sporting tour with a structure that can feel a bit unfamiliar for media professionals with little prior experience at our events. But we’re a friendly bunch and deeply appreciate all media interest in our sport. We’ve outlined the best methods by which you can gather content at our races or obtain information from afar to assist with your media projects. ON-SITE AT ONE OF OUR EVENTS 1. Apply For Accreditation Accreditation requests for World Cup events must be submitted individually to each Local Organising Committee (LOC) for the venue you wish to attend. Links to media accreditation for each World Cup venue are available on our website: Alpine > Media Information > Media Resources > Media Accreditation & Chiefs of Media https://www.fis-ski.com/en/alpine-skiing/media-information 2. Purchase Video/TV Rights [if applicable] The multimedia rights of the World Cup belong to the National Ski Associations who commission broadcast companies to manage those rights on their behalf. If you wish to film moving pictures with any kind of camera (even for social media use) or need footage from previous World Cup races, you must purchase the rights and obtain the necessary permission. For National rights Please contact the Chief of Media at the Local Organising Committee (LOC) for full information. The contacts are available on our website: Alpine > Media Information > Media Resources > Chiefs of Media https://www.fis-ski.com/en/alpine-skiing/media-information For International rights o For events hosted in Austria and Switzerland: Please contact EBU: [email protected] o For events hosted anywhere else in the world: Please contact Infront Italy: [email protected] 3. -

Validity of a Magnet-Based Timing System Using the Magnetometer Built Into an IMU

sensors Article Validity of a Magnet-Based Timing System Using the Magnetometer Built into an IMU Carla Pérez-Chirinos Buxadé 1 , Bruno Fernández-Valdés 1,2 ,Mónica Morral-Yepes 1 ,Sílvia Tuyà Viñas 1 , Josep Maria Padullés Riu 1 and Gerard Moras Feliu 1,* 1 National Institute of Physical Education of Catalonia (INEFC), University of Barcelona (UB), 08038 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] (C.P.-C.B.); [email protected] (B.F.-V.); [email protected] (M.M.-Y.); [email protected] (S.T.V.); [email protected] (J.M.P.R.) 2 School of Health Sciences, TecnoCampus, Pompeu Fabra University, 08302 Barcelona, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Inertial measurement units (IMUs) represent a technology that is booming in sports right now. The aim of this study was to evaluate the validity of a new application on the use of these wearable sensors, specifically to evaluate a magnet-based timing system (M-BTS) for timing short- duration sports actions using the magnetometer built into an IMU in different sporting contexts. Forty-eight athletes (22.7 ± 3.3 years, 72.2 ± 10.3 kg, 176.9 ± 8.5 cm) and eight skiers (17.4 ± 0.8 years, 176.4 ± 4.9 cm, 67.7 ± 2.0 kg) performed a 60-m linear sprint running test and a ski slalom, respectively. The M-BTS consisted of placing several magnets along the course in both contexts. The magnetometer built into the IMU detected the peak-shaped magnetic field when passing near the magnets at a certain speed. The time between peaks was calculated.