VU Research Portal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sexual Conflict in Hermaphrodites

Downloaded from http://cshperspectives.cshlp.org/ on October 1, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Sexual Conflict in Hermaphrodites Lukas Scha¨rer1, Tim Janicke2, and Steven A. Ramm3 1Evolutionary Biology, Zoological Institute, University of Basel, 4051 Basel, Switzerland 2Centre d’E´cologie Fonctionnelle et E´volutive, CNRS UMR 5175, 34293 Montpellier Cedex 05, France 3Evolutionary Biology, Bielefeld University, 33615 Bielefeld, Germany Correspondence: [email protected] Hermaphrodites combine the male and female sex functions into a single individual, either sequentially or simultaneously. This simple fact means that they exhibit both similarities and differences in the way in which they experience, and respond to, sexual conflict compared to separate-sexed organisms. Here, we focus on clarifying how sexual conflict concepts can be adapted to apply to all anisogamous sexual systems and review unique (or especially im- portant) aspects of sexual conflict in hermaphroditic animals. These include conflicts over the timing of sex change in sequential hermaphrodites, and in simultaneous hermaphrodites, over both sex roles and the postmating manipulation of the sperm recipient by the sperm donor. Extending and applying sexual conflict thinking to hermaphrodites can identify general evolutionary principles and help explain some of the unique reproductive diversity found among animals exhibiting this widespread but to date understudied sexual system. onceptual and empirical work on sexual strategy of making more but smaller gam- Cconflict is dominated by studies on gono- etes—driven by (proto)sperm competition— chorists (species with separate sexes) (e.g., Par- likely forced the (proto)female sexual strategy ker 1979, 2006; Rice and Holland 1997; Holland into investing more resources per gamete (Par- and Rice 1998; Rice and Chippindale 2001; ker et al. -

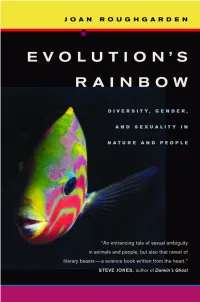

Joan Roughgarden

EVOLUTION’S RAINBOW Evolution’s Rainbow Diversity, Gender, and Sexuality in Nature and People Joan Roughgarden UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley Los Angeles London University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 2004 by Joan Roughgarden Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Roughgarden, Joan. Evolution’s rainbow : diversity, gender, and sexuality in nature and people / Joan Roughgarden. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-520-24073-1 1. Biological diversity. 2. Sexual behavior in animals. 3. Gender identity. 4. Sexual orientation. I. Title. qh541.15.b56.r68 2004 305.3—dc22 2003024512 Manufactured in the United States of America 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 10987654 321 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ansi/niso z39.48-1992(R 1997) (Per- manence of Paper). To my sisters on the street To my sisters everywhere To people everywhere Contents Introduction: Diversity Denied / 1 PART ONE ANIMAL RAINBOWS 1 Sex and Diversity / 13 2 Sex versus Gender / 22 3 Sex within Bodies / 30 4 Sex Roles / 43 5 Two-Gender Families / 49 6 Multiple-Gender Families / 75 7 Female Choice / 106 8 Same-Sex Sexuality / 127 9 The Theory of Evolution / 159 PART TWO HUMAN RAINBOWS 10 An Embryonic Narrative / 185 11 Sex Determination / 196 12 Sex Differences / 207 13 Gender Identity / 238 14 Sexual Orientation / 245 15 Psychological Perspectives / 262 16 Disease versus Diversity / 280 17 Genetic Engineering versus Diversity / 306 PART THREE CULTURAL RAINBOWS 18 Two-Spirits, Mahu, and Hijras / 329 19 Transgender in Historical Europe and the Middle East / 352 20 Sexual Relations in Antiquity / 367 21 Tomboi, Vestidas, and Guevedoche / 377 22 Trans Politics in the United States / 387 Appendix: Policy Recommendations / 401 Notes / 409 Index / 461 INTRODUCTION Diversity Denied On a hot, sunny day in June of 1997, I attended my first gay pride pa- rade, in San Francisco. -

Sexual Selection in a Simultaneous Hermaphrodite with Hypodermic Insemination: Body Size, Allocation to Sexual Roles and Paternity

ANIMAL BEHAVIOUR, 2003, 66, 417–426 doi:10.1006/anbe.2003.2255 ARTICLES Sexual selection in a simultaneous hermaphrodite with hypodermic insemination: body size, allocation to sexual roles and paternity LISA ANGELONI Section of Ecology, Behavior and Evolution, Division of Biology, University of California, San Diego (Received 30 January 2002; initial acceptance 13 April 2002; final acceptance 21 October 2002; MS. number: A9267R) Theory predicts that variation in body size within a population of simultaneous hermaphrodites should affect sex allocation, leading to individual differences in mating strategies and increased investment in female function with size. Small animals with fewer resources should invest proportionally more of their resources in male function than large animals, resulting in sperm displacement and paternity patterns that are independent of body size. This study investigated the effect of body size on mating patterns, egg production (an indirect measure of sperm transfer) and paternity in Alderia modesta, a sperm-storing, hermaphroditic sea slug with hypodermic insemination. The relative sizes of two hermaphrodites affected the probability and duration of inseminations; smaller animals inseminated larger mates for longer than vice versa. Sperm transfer began at a smaller size and age than egg production, and estimates of both sperm transfer and egg production increased with body size. Paternity patterns varied widely; in this species, unpredictable sperm precedence patterns may be a consequence of hypodermic insemina- tion and the lack of a well-defined sperm storage organ. Hypodermic injections across all sections of the body successfully transferred sperm and fertilized eggs. The function and consequences of hypodermic insemination are discussed. 2003 Published by Elsevier Ltd on behalf of The Association for the Study of Animal Behaviour. -

Glossary of Terminology

NOAA Coral Reef Information System - Glossary of Terminology Coral Reef Information System Home Data & Publications Regional Portals CRCP Activities Glossary HOME> GLOSSARY HOME> GLOSSARY OF TERMINOLOGY AND ACRONYMS/ABBREVIATIONS Glossary of Terminology A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | abalone a univalve mollusk (class Gastropoda) of the genus Haliotis. Abalones are harvested commercially for food consumption. The shell is lined with mother- of-pearl and used for commercial (ornamental) purposes Sea otters are in direct competition with humans for abalone. (Photo: Ron McPeak) abatement reducing the degree or intensity of, or eliminating abaxial away from, or distant from the axis abbreviate shortened abdomen in higher animals, the portion of the body that contains the intestines and other http://www.coris.noaa.gov/glossary/print-glossary.html[3/10/2016 11:56:15 AM] NOAA Coral Reef Information System - Glossary of Terminology viscera other than the lungs and heart; in arthropods, the rearmost segment of the body, which contains part of the digestive tract and all the reproductive organs The ventral surface of the abdomen of an American lobster. Prominent are the swimmerettes, uropods, and telson. abdominal fin a term used to describe the location of the pelvic (ventral) fins when they are inserted far behind pectorals. This is the more primitive condition. More recently evolved conditions have the pelvic fins in the thoracic or jugular positions. A salmon, for example, has its pelvic fins in the abdominal position. An angelfish has the pelvic fins in the thoracic position, and blennies have the pelvic fins in the jugular position, anterior to the pelvic girdle abductor a type of muscle whose function is to move an appendage or body part away from the body of an animal. -

A Nudibranch Removes Rival Sperm with a Disposable Spiny Penis

Journal of Ethology (2019) 37:21–29 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10164-018-0562-z ARTICLE A nudibranch removes rival sperm with a disposable spiny penis Ayami Sekizawa1,2 · Shin G. Goto1 · Yasuhiro Nakashima3 Received: 23 January 2018 / Accepted: 21 September 2018 / Published online: 27 October 2018 © The Author(s) 2019, corrected publication 2019 Abstract Simultaneous hermaphroditism is, at least initially, favoured by selection under low density — and therefore it can be assumed that sperm competition has little importance in this sexual system. However, many simultaneously hermaphroditic nudibranchs have both an allo-sperm storage organ (the seminal receptacle) and an allo-sperm digesting organ (the copu- latory bursa), suggesting the possibility of the occurrence of sperm competition. A nudibranch, Chromodoris reticulata, autotomizes its penis after every copulation and replenishes it within about 24 h to perform another copulation. We observed that the surface of the autotomized penis was covered with many backward-pointing spines and that a sperm mass was often entangled on the spines. This suggests that the nudibranch removes sperm that is already stored in a mating partner’s sperm storage organ(s) with its thorny penis. Using six microsatellite markers, we determined that the sperm mass attached to the penis were allo-sperm originating from individual(s) that had participated in prior copulations. We revealed that C. reticulata performed sperm removal using the thorny penis. These results suggest that competition in fertilization is quite intense and mating frequency in the wild is relatively high in this species. Keywords Sexual selection · Sperm removal · Sperm competition · Nudibranch · Simultaneous hermaphrodite Introduction et al. -

Comparative Embryology and Muscle Development of Polyclad Flatworms (Platyhelminthes: Rhabditophora) Diana Marcela Bolanos University of New Hampshire, Durham

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Fall 2008 Comparative embryology and muscle development of polyclad flatworms (Platyhelminthes: Rhabditophora) Diana Marcela Bolanos University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Bolanos, Diana Marcela, "Comparative embryology and muscle development of polyclad flatworms (Platyhelminthes: Rhabditophora)" (2008). Doctoral Dissertations. 439. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/439 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMPARATIVE EMBRYOLOGY AND MUSCLE DEVELOPMENT OF POLYCLAD FLATWORMS (PLATYHELMINTHES: RHABDITOPHORA) BY DIANA MARCELA BOLANOS BS, Universidad Jorge Tadeo Lozano, 2003 DISSERTATION Submitted to the University of New Hampshire In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Zoology September, 2008 UMI Number: 3333516 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ® UMI UMI Microform 3333516 Copyright 2008 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. -

2021.02.16.431427.Full.Pdf

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.16.431427; this version posted March 28, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. 1 Frequent origins of traumatic insemination 2 involve convergent shifts in sperm and 3 genital morphology 4 5 Jeremias N. Brand1*, Luke J. Harmon2 and Lukas Schärer1 6 7 1 University of Basel, Department of Environmental Sciences, Zoological Institute, Vesalgasse 1, 8 4051 Basel, Switzerland 9 2 Department of Biological Sciences, University of Idaho, Moscow, USA 10 11 Short title: 12 Frequent origins of traumatic insemination 13 14 *Corresponding Author 15 University of Basel, 16 Department of Environmental Sciences, Zoological Institute, 17 Vesalgasse 1, 4051 Basel, Switzerland 18 19 Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry 20 Department of Tissue Dynamics and Regeneration 21 Am Fassberg 11, 37077 Göttingen, Germany 22 Email: [email protected] 23 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.16.431427; this version posted March 28, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. 24 Abbreviations 25 HI: Hypodermic insemination 26 PC: principal component 27 pPCA: phylogenetically corrected principal component analysis 28 2 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.16.431427; this version posted March 28, 2021.