A Moral Attitude

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Film & History: an Interdisciplinary Journal of Film and Television Studies

Film & History: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Film and Television Studies Volume 38, Issue 2, 2008, pp. 107-109 http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/film_and_history/toc/flm.38.2.html Gaston Roberge, Satyajit Ray: Essays 1970-2005, Manohar, New Delhi (India), 2007, 280 pp., hb , ISBN: 81-7304-735-9 Reviewed by Gëzim Alpion In its scope and depth, Gaston Roberge’s new book on Satyajit Ray, is one of the most important publications to appear on this great twentieth-century film director since his 1992 death. The book includes twenty-four essays, which were written between 1970 and 2005. The timeline is important to trace the growth and maturity of Ray’s art as well as Roberge’s admiration for and appreciation of his oeuvre. The essays were originally prompted by teaching assignments and requests for articles as well as by Roberge’s long-standing and growing interest in the work and talent of the Calcutta-born filmmaker. Only Essay 8, the discussion of Jana Aranya (The Middle Man, 1975), was written for this collection to ‘complement’ the book and ‘improve’ Roberge’s ‘perception of the evolution’ (p. 14) he seeks to describe from the Apu trilogy to the Heart trilogy. Some of the essays have been edited slightly by the author to avoid repetition and, more importantly, to reflect important changes in technology since the time the articles were first published. So, for instance, in Essay 13, which appeared in print initially in 1974, Roberge rightly argues that the editing was warranted by the fact that, in the digital era, the technology of film can no longer be defined solely as the succession of still images. -

POWERFUL and POWERLESS: POWER RELATIONS in SATYAJIT RAY's FILMS by DEB BANERJEE Submitted to the Graduate Degree Program in Fi

POWERFUL AND POWERLESS: POWER RELATIONS IN SATYAJIT RAY’S FILMS BY DEB BANERJEE Submitted to the graduate degree program in Film and Media Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s of Arts ____________________ Chairperson Committee members* ____________________* ____________________* ____________________* ____________________* Date defended: ______________ The Thesis Committee of Deb Banerjee certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: POWERFUL AND POWERLESS: POWER RELATIONS IN SATYAJIT RAY’S FILMS Committee: ________________________________ Chairperson* _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Date approved:_______________________ ii CONTENTS Abstract…………………………………………………………………………….. 1 Introduction……………………………………………………………………….... 2 Chapter 1: Political Scenario of India and Bengal at the Time Periods of the Two Films’ Production……………………………………………………………………16 Chapter 2: Power of the Ruler/King……………………………………………….. 23 Chapter 3: Power of Class/Caste/Religion………………………………………… 31 Chapter 4: Power of Gender……………………………………………………….. 38 Chapter 5: Power of Knowledge and Technology…………………………………. 45 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………. 52 Work Cited………………………………………………………………………... 55 i Abstract Scholars have discussed Indian film director, Satyajit Ray’s films in a myriad of ways. However, there is paucity of literature that examines Ray’s two films, Goopy -

Satyajit Ray at 100: Why Sharmila Tagore Considers 'Devi' Her Best

TALKING FILMS Satyajit Ray at 100: Why Sharmila Tagore considers ‘Devi’ her best collaboration with the master The 1960 classic, an examination of the tussle between blind faith and rationality, was one of five Ray productions to feature Tagore. Sharmila Tagore Jan 27, 2021 · 03:30 pm Sharmila Tagore in Satyajit Ray’s Devi (1960) | Satyajit Ray Productions Satyajit Ray arrived on the planet nearly a hundred years ago in 1921 and in the world of cinema with Pather Panchali in 1955. Devi, released in 1960, was his sixth feature, and followed the Apu Trilogy, Parash Pathar and Jalsaghar. Apur Sansar, the concluding chapter of the trilogy, introduced Soumitra Chatterjee and Sharmila Tagore. Both actors would become an indelible part of Ray’s cinematic universe. The haunting Devi, set in nineteenth-century Bengal and at the intersection of blind faith and rationality, was Tagore’s first lead role. She plays Doyamayee, a member of an aristocratic family who is declared to be the living embodiment of the goddess Kali by her father- in-law Kalikinkar (Chhabi Biswas). The gentle and tradition-bound Doyamayee is unable to resist the cult that builds up around her. Her husband Umaprasad (Soumitra Chatterjee) is equally unable to persuade his father that his wife is all too human. Adapted by Ray from a short story by Prabhat Kumar Mukherjee and beautifully shot by Subrata Mitra and designed by Bansi Chadragupta, Devi provides an early peek into Tagore’s estimable acting abilities. Then only 14 years old, Tagore delivered what she describes in the following essay as her “favourite performance”. -

Pather Panchali Aparajito the World of Apu Trois Couleurs: Bleu

Trilogies (of sorts) January 11, 2016 Pather Panchali (1955) 1:59 Dir. Satyajit Ray in Bengali The first of the Apu Trilogy — Impoverished priest, dreaming of a better English subtitles life for himself and his family, leaves his rural Bengal village in search (b&w) of work. January 25, 2016 Aparajito (1956) 1:50 Dir. Satyajit Ray in Bengali The second of the Apu Trilogy — Following his father's death, a boy English subtitles leaves home to study in Calcutta, while his mother must face a life (b&w) alone. February 8, 2016 The World of Apu (1959) 1:58 Dir. Satyajit Ray in Bengali Third and final film of the Apu Trilogy — Follows Apu's life as an English subtitles orphaned adult aspiring to be a writer as he lives through poverty, and (b&w) the unforeseen turn of events. February 22, 2016 Trois Couleurs: Bleu (1993) 1:38 Dir. Krzysztof Kieslowski in French A woman struggles to find a way to live her life after the death of her English subtitles husband and child. (color) All Movies 7:30 pm at the Dignity/Washington Center Trilogies (of sorts) March 7, 2016 Trois Couleurs: Blanc (1994) 1:31 Dir. Krzysztof Kieslowski in French Second of a trilogy of films dealing with contemporary French society English subtitles shows a Polish immigrant who wants to get even with his former wife. (color) March 21, 2016 Trois Couleurs: Rouge (1994) 1:39 Dir. Krzysztof Kieslowski in French Final entry in a trilogy of films dealing with contemporary French English subtitles society concerns a model who discovers her neighbor is keen on (color) invading people's privacy. -

Portrayal of Environment in Cinema: a Comparative Study of 'Pather Panchali'

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Research International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Research ISSN: 2455-2070; Impact Factor: RJIF 5.22 www.socialsciencejournal.in Volume 3; Issue 5; May 2017; Page No. 45-48 Portrayal of environment in cinema: A comparative study of ‘Pather panchali’ & ‘Dreams’ Ram Prakash Dwivedi Department of Hindi journalism & Mass Communication, Dr. B.R. Ambedkar College, University of Delhi, New Delhi, India Abstract Satyajit Ray (1921-1992) and Akira Kurosawa (1910-198) are the world-famous filmmakers. Coincidentally, they were contemporary and friends. They were also sources of inspiration for each other. Their films are a landmark example of creative cine-language. In most of their movies, nature and the environment are as important as the human characters. Rather, the human being is guided by the nature to act upon. Their movies incorporate nature as an essential component for human activities. Portrayal of nature, in Ray’s movies, is different from that of Kurosawa. To Ray’s films environment and nature comes as part of daily life or seasonal change, whereas Kurosawa represents nature as phenomena like rain, volcanic eruptions, tsunami and earthquakes. This difference is the result of separate geographical conditions of India and Japan. Japan is environmentally very sensitive country, whereas India, due to its larger landmass, does not feel such sensitivity. Pather Panchali (1955) is considered as a masterpiece of parallel cinema and reflects reality. The film was made with on location shooting technique. This film, therefore, depicts the nature and environment of Bengal. In Dreams (1990) imagination is more important than reality. -

Artist Recreates Satyajit Ray S Film Posters on 100Th Birth Anniversary

Artist recreates Satyajit Ray's film posters on 100th birth anniversary to depict Covid crisis An artist marked 100 years of legendary filmmaker Satyajit Ray by recreating his iconic film posters to depict the Covid-19 crisis in India. Krishna Priya Pallavi Writer [email protected] If I am not writing on fashion, places you can travel to for that perfect holiday, mental health, trending topics, I am probably escaping the city for a vacation, eating a scrumptious meal at a quaint cafe, and so much more in between. Love to travel (obviously), dance, explore new places, read extensively and try out new and exciting dishes. Works as Senior Sub-Editor at India Today Digital. Aniket Mitra used posters from Satyajit Ray's iconic films to depict the Covid-19 crisis going on in India Photo: Facebook/Aniket Mitra Satyajit Ray had an inedible mark on the Indian cinema. His films are admired by cinephiles all over the world. May 2 marks 100 years since Satyajit Ray was born, and to celebrate his 100th birth anniversary, an artist paid the legendary filmmaker a poignant and relevant tribute. A Mumbai-based artist named Aniket Mitra celebrated the historic day by reimagining Satyajit Ray's iconic film posters amid the Covid times. ARTIST RECREATES SATYAJIT RAY'S FILM POSTERS TO DEPICT COVID CRISIS Aniket Mitra used ten films by Satyajit Ray to depict the Covid-19 crisis going on in India. Posters of films like Pather Panchali, Devi, Nayak, Seemabaddha, Jana Aranya, Mahanagar, Ashani Sanket and more, were used to show the citizens' struggle during the second wave of the deadly virus. -

Mahanagar Gas Limited Consistent Margin Outperformance; Earnings Outlook Improving

Mahanagar Gas Limited Consistent margin outperformance; earnings outlook improving Powered by the Sharekhan 3R Research Philosophy Oil & Gas Sharekhan code: MGL Result Update Update Stock 3R MATRIX + = - Summary Right Sector (RS) ü Q3FY2021 operating profit/PAT at Rs. 317 crore/Rs. 217 crore; up 22.4%/16.7% y-o-y and in-line with our estimates but were higher by 12%/10% versus consensus estimates led by Right Quality (RQ) ü a sharp recovery in gas sales volumes (up 32.2% q-o-q) and record-high EBITDA margins of Rs. 12.4/scm (up 34.8% y-o-y). Right Valuation (RV) ü CNG/Domestic PNG volume stood at 85%/124% of pre-COVID-19 level at 1.9 mmscmd/0.5 mmscmd; Industrial/Commercial (I/C) PNG volume declined by 9% y-o-y. Highest ever + Positive = Neutral - Negative gross margins of Rs. 17.7/scm (up 27.6% y-o-y). Improving volume and sustainable high margin bode well for a strong Q4FY21. Double- What has changed in 3R MATRIX digit volume growth guidance for FY22 and a 5-6% growth thereafter would drive an 18% PAT CAGR over FY21E-FY23E. Old New MGL’s underperformance to Sensex is likely to reverse as earnings outlook has improved and overhang of open access is over. Valuation of 12.1x its FY23E EPS is most attractive in RS the CGD space. We retain Buy on MGL with an unchanged PT of Rs. 1,380. RQ Mahanagar Gas Limited’s (MGL) Q3FY2021 operating profit of Rs. 317 crore (up 22.4% y-o-y; up 43.3% q-o-q) was in line with our estimates but 12% higher-than the consensus estimate RV of Rs. -

Pather Panchali

February 19, 2002 (V:5) Conversations about great films with Diane Christian and Bruce Jackson SATYAJIT RAY (2 May 1921,Calcutta, West Bengal, India—23 April 1992, Calcutta) is one of the half-dozen universally P ATHER P ANCHALI acknowledged masters of world cinema. Perhaps the best starting place for information on him is the excellent UC Santa Cruz (1955, 115 min., 122 within web site, the “Satjiyat Ray Film and Study Collection” http://arts.ucsc.edu/rayFASC/. It's got lists of books by and about Ray, a Bengal) filmography, and much more, including an excellent biographical essay by Dilip Bausu ( Also Known As: The Lament of the http://arts.ucsc.edu/rayFASC/detail.html) from which the following notes are drawn: Path\The Saga of the Road\Song of the Road. Language: Bengali Ray was born in 1921 to a distinguished family of artists, litterateurs, musicians, scientists and physicians. His grand-father Upendrakishore was an innovator, a writer of children's story books, popular to this day, an illustrator and a musician. His Directed by Satyajit Ray father, Sukumar, trained as a printing technologist in England, was also Bengal's most beloved nonsense-rhyme writer, Written by Bibhutibhushan illustrator and cartoonist. He died young when Satyajit was two and a half years old. Bandyopadhyay (also novel) and ...As a youngster, Ray developed two very significant interests. The first was music, especially Western Classical music. Satyajit Ray He listened, hummed and whistled. He then learned to read music, began to collect albums, and started to attend concerts Original music by Ravi Shankar whenever he could. -

Beyond the World of Apu: the Films of Satyajit Ray'

H-Asia Sengupta on Hood, 'Beyond the World of Apu: The Films of Satyajit Ray' Review published on Tuesday, March 24, 2009 John W. Hood. Beyond the World of Apu: The Films of Satyajit Ray. New Delhi: Orient Longman, 2008. xi + 476 pp. $36.95 (paper), ISBN 978-81-250-3510-7. Reviewed by Sakti Sengupta (Asian-American Film Theater) Published on H-Asia (March, 2009) Commissioned by Sumit Guha Indian Neo-realist cinema Satyajit Ray, one of the three Indian cultural icons besides the great sitar player Pandit Ravishankar and the Nobel laureate Rabindra Nath Tagore, is the father of the neorealist movement in Indian cinema. Much has already been written about him and his films. In the West, he is perhaps better known than the literary genius Tagore. The University of California at Santa Cruz and the American Film Institute have published (available on their Web sites) a list of books about him. Popular ones include Portrait of a Director: Satyajit Ray (1971) by Marie Seton and Satyajit Ray, the Inner Eye (1989) by Andrew Robinson. A majority of such writings (with the exception of the one by Chidananda Dasgupta who was not only a film critic but also an occasional filmmaker) are characterized by unequivocal adulation without much critical exploration of his oeuvre and have been written by journalists or scholars of literature or film. What is missing from this long list is a true appreciation of his works with great insights into cinematic questions like we find in Francois Truffaut's homage to Alfred Hitchcock (both cinematic giants) or in Andre Bazin's and Truffaut's bio-critical homage to Orson Welles. -

Satyajit Ray

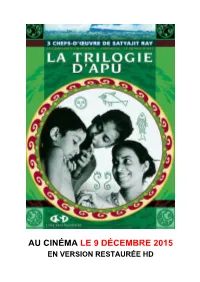

AU CINÉMA LE 9 DÉCEMBRE 2015 EN VERSION RESTAURÉE HD Galeshka Moravioff présente LLAA TTRRIILLOOGGIIEE DD’’AAPPUU 3 CHEFS-D’ŒUVRE DE SATYAJIT RAY LLAA CCOOMMPPLLAAIINNTTEE DDUU SSEENNTTIIEERR (PATHER PANCHALI - 1955) Prix du document humain - Festival de Cannes 1956 LL’’IINNVVAAIINNCCUU (APARAJITO - 1956) Lion d'or - Mostra de Venise 1957 LLEE MMOONNDDEE DD’’AAPPUU (APUR SANSAR - 1959) Musique de RAVI SHANKAR AU CINÉMA LE 9 DÉCEMBRE 2015 EN VERSION RESTAURÉE HD Photos et dossier de presse téléchargeables sur www.films-sans-frontieres.fr/trilogiedapu Presse et distribution FILMS SANS FRONTIERES Christophe CALMELS 70, bd Sébastopol - 75003 Paris Tel : 01 42 77 01 24 / 06 03 32 59 66 Fax : 01 42 77 42 66 Email : [email protected] 2 LLAA CCOOMMPPLLAAIINNTTEE DDUU SSEENNTTIIEERR ((PPAATTHHEERR PPAANNCCHHAALLII)) SYNOPSIS Dans un petit village du Bengale, vers 1910, Apu, un garçon de 7 ans, vit pauvrement avec sa famille dans la maison ancestrale. Son père, se réfugiant dans ses ambitions littéraires, laisse sa famille s’enfoncer dans la misère. Apu va alors découvrir le monde, avec ses deuils et ses fêtes, ses joies et ses drames. Sans jamais sombrer dans le désespoir, l’enfance du héros de la Trilogie d’Apu est racontée avec une simplicité émouvante. A la fois contemplatif et réaliste, ce film est un enchantement grâce à la sincérité des comédiens, la splendeur de la photo et la beauté de la musique de Ravi Shankar. Révélation du Festival de Cannes 1956, La Complainte du sentier (Pather Panchali) connut dès sa sortie un succès considérable. Prouvant qu’un autre cinéma, loin des grosses productions hindi, était possible en Inde, le film fit aussi découvrir au monde entier un auteur majeur et désormais incontournable : Satyajit Ray. -

Western Influences on the Three Bengali Poets of the 30S Sultana Jahan

International Journal of English Literature and Social Sciences (IJELS) Vol-3, Issue-2, Mar - Apr, 2018 https://dx.doi.org/10.22161/ijels.3.2.6 ISSN: 2456-7620 Western Influences on the three Bengali Poets of the 30s Sultana Jahan Assistant Professor, Department of English Language and Literature, International Islamic University Chittagong, Bangladesh Abstract— Modernism came to exercise an influence in Bangladesh's poets in the way it once did with Baudelaire and Eliot. For these western poets, the romantic notion was replaced with desperation and despondency and loneliness of modern minds. JibanadaDas, Budda Dev Bose, shudindranath Dutt, Amiochacrabarti, and Bishnudey, all of them being the professors of English Literature, successfully incorporated Western Modernist outlook with a view to shaking off Tagore’s romantic perception.They were much influenced by French imagist and symbolist movement, French surrealist poets, Garman expressionist poets and other modernists. Sometimes they incorporates Eatsian ideology, sometimes they followed Eliotic view, and sometimes they followed Marxist Theory or Freudian psychoanalysis. Though, these modernist poets take on different styles and ways to reveal the alienation, hypocrisy and anxiety of modern man, they perceive the fact that to reflect the post-war modern world, there is no alternative of discarding romantic notion about life. This paper will shed light on three poets, Jibananda Das, AmioCakrabarti, and BishnuDey and the Western Modernist philosophy that has molded their poetic career. Keywords— creative violence, impressionism, surrealism, agnosticism. “The practice of Rabindranath is poetry became unsuccessful to give solace to the mind of Bengali poets. At least, a few important Bengali poets tried to step aside and avoid Rabindranath and welcomed the positive or negative vision of Mallarme, Paul Verlaine, Rossenr, Yeats or Eliot.” (Das, Kabitar Katha, p. -

APARAJITO/THE UNVANQUISHED (1956) 110 Min

3 October 2006 XIII:5 APARAJITO/THE UNVANQUISHED (1956) 110 min. Produced, written and directed by Satyajit Ray Based on the novel by Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay Original Music by Ravi Shankar Cinematography by Subrata Mitra Film Editing by Dulal Dutta Kanu Bannerjee ... Harihar Ray Karuna Bannerjee ... Sarbojaya Ray Pinaki Sengupta ... Apu (young) Smaran Ghosal ... Apu (adolescent) Santi Gupta ... Ginnima Ramani Sengupta ... Bhabataran Ranibala ... Teliginni Sudipta Roy ... Nirupama Ajay Mitra ... Anil Charuprakash Ghosh ... Nanda Subodh Ganguli ... Headmaster Mani Srimani ... Inspector Hemanta Chatterjee ... Professor Kali Bannerjee ... Kathak Kalicharan Roy ... Akhil, press owner Kamala Adhikari ... Mokshada Lalchand Banerjee ... Lahiri K.S. Pandey ... Pandey Meenakshi Devi ... Pandey's wife Anil Mukherjee ... Abinash Harendrakumar Chakravarti ... Doctor Bhaganu Palwan ... Palwan SATYAJIT RAY (2 May 1921, Calcutta, West Bengal, British India—23 April 1992, Calcutta, West Bengal, India) directed 37 films. He is best known in the west for the Apu Trilogy— Apur Sansar/The World of Apu (1959), Aparajito/The Unvanquished (1957), and (his first film) Pather Panchali/Song of the Road (1955) and for Jalsaghar/The Music Room (1958). His last films were Agantuk (1991), Shakha Proshakha (1990), Ganashatru/An Enemy of the People (1989), Sukumar Ray (1987), Ghare-Baire/The Home and the World (1984) and Heerak Rajar Deshe/The Kingdom of Diamonds (1980). He was given an honorary Academy Award in 1992. SUBRATA MITRA (12 October 1930, Calcutta, West Bengal, India—7 December 2001) shot 17 films, 10 of them for Ray, including all three Apu films, Jalsaghar/The Music Room (1958) and Parash Pathar/The Philosopher’s Stone (1958). His last film was New Delhi Times (1986).