Oral History Interview with Rackstraw Downes, 2016 April 10-11

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

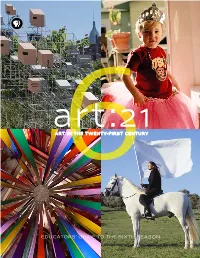

Screening Guides to the Sixth Season

art:21 screening guides to the sixth season © Art21 2012. All Rights Reserved. www.pbs.org/art21 | www.art21.org season six GETTING STARTED ABOUT THIS SCREENING GUIDE unique opportunity to experience first-hand the complex artistic process—from inception to finished This screening guide is designed to help you plan product—behind some of today’s most thought- an event using Season Six of Art in the Twenty-First provoking art. These artists represent the breadth Century. This guide includes an episode synopsis, of artistic practices across the country and the artist biographies, discussion questions, group world and reveal the depth of intergenerational activities, and links to additional resources online. and multicultural talent. Educators’ Guide The 32-page color manual ABOUT ART21 SCREENING EVENTS includes information on the ABOUT ART21, INC. artists, before-viewing and Public screenings of the Art in the Twenty-First after-viewing questions, and Century series illuminate the creative process of Art21 is a non-profit contemporary art organization curriculum connections. today’s visual artists by stimulating critical reflection serving students, teachers, and the general public. FREE | www.art21.org/teach as well as conversation in order to deepen Art21’s mission is to increase knowledge of contem- audience’s appreciation and understanding of porary art, ignite discussion, and empower viewers contemporary art and ideas. Organizations and to articulate their own ideas and interpretations individuals are welcome to host their own Art21 about contemporary art. Art21 seeks to achieve events year-round. Art21 invites museums, high this goal by using diverse media to present an schools, colleges, universities, community-based independent, behind-the scenes perspective on organizations, libraries, art spaces and individuals contemporary art and artists at work and in their to get involved and create unique screening own words. -

Rackstraw Downes

RACKSTRAW DOWNES 1939 Born in Kent, England 1961 BA in English Literature, Cambridge University, England 1961-62 English-Speaking Union Traveling Fellowship 1963-64 BFA and MFA in Painting, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 1964-65 Post-Graduate Fellowship. University of Pennsylvania 1967-79 Teaches painting at the University of Pennsylvania 1969 Marjorie Heilman Visiting Artist, Swarthmore College, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania 1971 Yaddo Residence Fellowship 1974 Ingram Merrill Fellowship 1978 CAPS 1980 National Endowment for the Arts Grant 1989 Academy-Institute Award, American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters 1998 John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship 1999 Inducted into the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters 2009 Delivered Ninth Annual Raymond Lecture for the Archives of American Art 2009 The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Fellowship The artist lives and works in New York City and Presidio, Texas Solo Exhibitions 2018 Rackstraw Downes, Betty Cuningham Gallery, New York, NY, Sept 5-Oct 14 2014 Rackstraw Downes, Betty Cuningham Gallery, New York, NY, April 3- May 3 2012 Rackstraw Downes, Betty Cuningham Gallery, New York, NY, Oct. 11 – Nov. 24 2010-11 Rackstraw Downes: Onsite Paintings, 1974–2009, The Parrish Art Museum, Southampton, New York; travels to: Portland Museum of Art, Portland, ME; Weatherspoon Art Museum, Greensboro, NC Rackstraw Downes: Under the Westside Highway, The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Ridgefield, CT 2010 Rackstraw Downes: A Selection of Drawings 1980-2010, Betty -

American Art Today: Contemporary Landscape the Art Museum at Florida International University Frost Art Museum the Patricia and Phillip Frost Art Museum

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons Frost Art Museum Catalogs Frost Art Museum 2-18-1989 American Art Today: Contemporary Landscape The Art Museum at Florida International University Frost Art Museum The Patricia and Phillip Frost Art Museum Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/frostcatalogs Recommended Citation Frost Art Museum, The Art Museum at Florida International University, "American Art Today: Contemporary Landscape" (1989). Frost Art Museum Catalogs. 11. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/frostcatalogs/11 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the Frost Art Museum at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Frost Art Museum Catalogs by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RIGHT: COVER: Howard Kanovitz Louisa Matthiasdottir Full Moon Doors, 1984 Sheep with Landscape, 1986 Acrylic on canvas/wood construction Oil on canvas 47 x 60" 108 x ;4 x 15" Courtesy of Robert Schoelkopf Gallery, NY Courtesy of Marlborough Gallery, NY American Art Today: Contemporary Landscape January 13 - February 18, 1989 Essay by Jed Perl Organized by Dahlia Morgan for The Art Museum at Florida International University University Park, Miami, Florida 33199 (305) 554-2890 Exhibiting Artists Carol Anthony Howard Kanovitz Robert Berlind Leonard Koscianski John Bowman Louisa Matthiasdottir Roger Brown Charles Moser Gretna Campbell Grover Mouton James Cook Archie Rand James M. Couper Paul Resika Richard Crozier Susan Shatter -

Rackstraw Downes a Wider View

Credits This catalog was published on the occasion of Rackstraw Downes: A Wider View, an exhibition curated by Downes Rackstraw Andrea Packard for the List Gallery, Swarthmore College, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania, March 5–April 5, 2020. Rackstraw Downes A Wider View © 2019 List Gallery, Swarthmore College All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part including illustrations, in any form (beyond copying A Wider View A permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of U. S. Copyright Law and except by reviewer for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. ISBN: 978-0-9993904-3-6 Library of Congress Control Number: 2020900653 I think our culture has to learn a whole new relatedness to the physical world, and that in order to attune ourselves to this we need an art not of reference but of presence—of the physical thing itself in its integrity. —RACKSTRAW DOWNES Inside front cover: Rackstraw Downes, Nature and Art Are Physical, Writings on Art, 1967–2008, pp. 269-270. Front cover and back cover: A Fence at the Periphery of a Jersey City Scrap Metal Yard (detail), 1993 oil on canvas, 15 x 116 inches. Courtesy of The William Louis-Dreyfus Foundation Inc. Photo on page 46: c. 1989-90, Varick Street, near Holland Tunnel entrance, New York City © 2019 Andrea Packard for “Rackstraw Downes’s Landscapes of Experience.” © 2019 Alfred Mac Adam for “Rackstraw Downes: the Wider View.” Catalog Editor: Andrea Packard Design: Phillip Unetic, UneticDesign.com Printing: Brilliant, Exton PA List Gallery Swarthmore College G42711_RackStrawCOV_REVISE_2.4.20.indd All Pages 2/11/20 10:02 AM Rackstraw Downes A Wider View March 5—April 5, 2020 List Gallery, Swarthmore College G42711_RackStrawTXT_REVISE_2.4.20.indd 1 2/7/20 11:54 AM Rackstraw Downes’s Landscapes of Experience Andrea Packard List Gallery Director The List Gallery is pleased to present Rackstraw Downes: A Wider View. -

Rackstraw Downes: a Wider View / March 5–April 5, 2020

List GALLERY / SWARTHMORE COLLEGE / 500 COLLEGE AVENUE / SWARTHMORE, PA 19081 Contact Andrea Packard: 610-328-8488 / email: [email protected] www.swarthmore.edu/list-gallery / www.swarthmore.edu/visitors/directions-to-campus Rackstraw Downes, Presidio: In the Sand Hills Looking East with ATV Tracks and Water Tower, 2012, oil on canvas, 16 1⁄2 x 65 1⁄4 inches. Courtesy of Betty Cuningham Gallery, New York Rackstraw Downes: A Wider View / March 5–April 5, 2020 Thursday, March 5 4:30 PM: Presentations and discussion, Scheuer Room, KohlBerg Hall Introduction by List Gallery Director Andrea Packard, exhibition curator Rackstraw Downes: A Wider View, a short video by Tess Wei "The Radical Possibility of Seeing What is Directly in Front of You," by John Yau John Yau has published more than 50 books of poetry, artists' books, fiction, and art criticism. Yau was the arts editor of The Brooklyn Rail from 2007-2011, and has subsequently served as weekend editor for the online magazine, Hyperallergic. Yau's numerous honors include awards from Creative Capital/Warhol Foundation, the Ingram Merrill Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, the New York Foundation for the Arts, the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, and the Foundation for Contemporary Arts. 5:30—7:00 PM: Opening reception, List Gallery, Lang Performing Arts Center Sunday, April 5 4:00 PM: "As Far as the Eye Can See," List Gallery talk by Robert Storr ’72 Robert Storr is an artist, critic, curator, and the author of numerous numerous books, catalogs, essays, and reviews. From 1990 until 2002, first as curator and then as senior curator in the Department of Painting and Sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, he organized numerous exhibitions, including Modern Art Despite Modernism and retrospectives of Tony Smith, Chuck Close, Gerhard Richter, Max Beckmann, and Elizabeth Murray. -

PRESS INFORMATION Press Contact | [email protected]

PRESS INFORMATION Press Contact | [email protected] "A Game-Changer for Maine Art." – Alex Katz 21 Winter Street, Rockland, Maine Public Opening | June 26, 2016 Over the course of its sixty-four year history, the Center for Maine Contemporary Art (CMCA) has introduced the work of hundreds of contemporary artists—both well known and emerging—to audiences in Maine. CMCA is now opening a whole new chapter in contemporary art in the state. Its compelling new home in the heart of Rockland’s downtown arts district is destined to be—in the words of artist Alex Katz—“a game-changer for Maine art.” The New CMCA 1 Contemporary Since 1952 2 A Legacy of Artists 3 An Active Community Participant 4 Extending CMCA’s Educational Impact 5 CMCA by the Numbers 6 2016 Opening Season Exhibitions 7 Rockland, Maine 8 Toshiko Mori Architect 9 The New CMCA In summer 2016, CMCA will open a newly constructed 11,500+ square foot building, with 5,500 square feet of exceptional exhibition space, designed by award-winning architect Toshiko Mori (New York and North Haven, Maine). Located in the heart of downtown Rockland, Maine, across from the Farnsworth Art Museum and adjacent to the historic Strand Theatre, the new CMCA has three exhibition galleries (one which doubles as a lecture hall/performance space), a gift shop, ArtLab classroom, and a 2,200 square feet open public courtyard. The new building and location enables CMCA to pursue its core mission of fostering contemporary art on a new and elevated level. The glass-enclosed space, with its corru- gated metal exterior and emphasis on Maine’s legendary light, is unlike anything else in the state. -

Lois Dodd | Landscapes and Structures a Painting Survey April 10 Through May 30, 2008 Reception for the Artist Thursday, April 10, from 5 to 7 Pm

Lois Dodd | Landscapes and Structures A Painting Survey April 10 through May 30, 2008 Reception for the artist Thursday, April 10, from 5 to 7 pm For over fifty years Lois Dodd has painted her immediate everyday surrounds at the places she has chosen to live: New York’s Lower East Side, rural mid-coast Maine, and the Delaware Water Gap. Focusing on the latter two locations, this exhibition will present the motifs of structures in the landscape and structures within the landscape that she has returned to again and again over her career. The exhibition will be comprised of over forty-five mostly small-scaled oil paintings on wood or masonite panels. These portable panels are part of a spontaneous working method that enables Dodd to capture the atmosphere of a day or the mood of an evening—working beside a road, in a quarry, or on a neighbor’s property. With titles such as House and Barn (1967), Barn Door and Chicken House (1970), Roses and New Shingles (1984), Snow and Spruce(1989), and Apple Blossoms Behind Out Buildings (2007), Dodd presents her subjects with an unsentimental, no-nonsense directness grounded in observation, yet boldly simplified with the active, painterly marks and surfaces of early American and European modernism. Grace Glueck, writing in a 2003 review of the gallery’s first Dodd show, says: Translating the commonplace into art has long been the province of Lois Dodd . who celebrates the richness of everyday life. Simple as the work seems, it touches the transcendental. The painter and critic Robert Berlind similarly noted in 2004: One feels that she downplays detailed, literal description not out of some modernist impera-tive but, as the Shaker hymn puts it, because she has “a gift to be simple” and with that temperamental dispensation, “a gift to be free.” . -

Arts in the Belgrades History

Art in the Belgrades: A Preliminary Look at the History of Visual Art, Literature, and Music in the Belgrade Lakes Region James S. Westhafer’10 Science, Technology, and Society Program Colby College Waterville, Maine Belgrade Lakes History, Geology, and Sense of Place Project May 2010 This research is supported by National Science Foundation award #EPS-0904155 to Maine EPSCoR at the University of Maine. 2 While thousands of tourists flood the Belgrade lakes region of central Maine every year to utilize the area’s numerous outdoor activities and enjoy the picturesque views, many of them are unaware of the long, rich history of this dreamland. The continued health of the Belgrades necessitates not only respect and appreciation for the beautiful countryside, but also an understanding of the comprehensive history of the region. One of the major components of a comprehensive historical study is examining the art related to the seven major lakes, thirteen municipalities and surrounding Maine landscape. Through my investigation of Belgrade artists and pieces of art influenced by this central Maine region, I have compiled an original historical narrative of art affiliated with this central Maine environment. Throughout my research on this project, I have not come across a single document or piece of published literature discussing this topic. This comes as a great surprise to me, as the Belgrade region of Maine is known for its remoteness and serenity; characteristics that embody landscape art. Talking with historians of the region such as Nan Mairs, town historian of Belgrade, and David Richards, assistant director of the Margaret Smith Chase (MSC) Library, confirmed my suspicion. -

Download-To-Own from the and Educational Resources

art:21 educators’ guide to the sixth season Art21 Staff Executive Director/ Series Executive Producer, Director, Curator: Susan Sollins Managing Director/ Series Producer: Eve Moros Ortega Associate Curator: Wesley Miller Director, Art21 Educators: Jessica Hamlin Senior Education Advisor: Joe Fusaro Manager of Digital Media and Strategy: Jonathan Munar Director of Development: Diane Vivona Development Associate: KC Forcier Development Assistant: Heather Reyes Director of Production: Nick Ravich Production Coordinator: Ian Forster Art21 Series Contributors Consulting Directors: Charles Atlas, Catherine Tatge Series Editors: Lizzie Donahue, Mark Sutton Companion Book & Educators’ Guide Design: Russell Hassell Companion Book & Educators’ Guide Editor: Marybeth Sollins Art21 Education and Public Programs Advisory Council Christin Baker, YMCA of the USA; Laura Beiles, Museum of Modern Art; Susan Chun, Cultural Heritage Consulting; William Crow, Metropolitan Museum of Art; Dipti Desai, New York University; Rosanna Flouty, Educational Consultant; Tyler Green, Modern Art Notes Media; Olivia Gude, University of Illinois at Chicago; Jeanne Hoel, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; Eliza Licht, POV; Nate Morgan, Hillside School; Frank Smigiel, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Mary Ann Stankiewicz, Penn State University. Funders Lead Sponsorship of Season Six Education programs and materials has been provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. Major underwriting for Season Six of Art in the Twenty-First Century and its accompanying education -

"A Game-Changer for Maine Art." – Alex Katz

"A Game-Changer for Maine Art." – Alex Katz 21 Winter Street, Rockland, Maine Public Opening | June 26, 2016 PRESS INFORMATION Press Contact | Kristen N. Levesque +1.207.329.3090 | [email protected] Table of Contents Over the course of its 64 year history, the Center for Maine Contemporary Art (CMCA) has introduced the work of hundreds of contemporary artists—both well known and emerging—to audiences in Maine and beyond. CMCA is opening a new chapter in contemporary art in the state of Maine. Its new home in the heart of Rockland’s downtown arts district is destined to be—in the words of artist Alex Katz—“a game-changer for Maine art.” The New CMCA 3 Contemporary Since 1952 4 A Legacy of Artists 5 An Active Community Participant 6 Extending CMCA’s Educational Impact 7 CMCA by the Numbers 8 2016 Opening Season Exhibitions 9 Rockland, Maine 10 Toshiko Mori Architect 11 CMCANOW.ORG 2 The New CMCA In summer 2016, CMCA will open a newly constructed 11,500+ square foot building, with 5,500 square feet of exceptional exhibition space, designed by award-winning architect Toshiko Mori, FAIA, (New York and North Haven, Maine). Located in the heart of downtown Rockland, Maine, across from the Farnsworth Art Museum and adjacent to the historic Strand Theatre, the new CMCA has three exhibition galleries (one which doubles as a lecture hall/performance space), a gift shop, ArtLab classroom, and a 2,200 square foot courtyard open to the public. The new building and location enables CMCA to pursue its core mission of fostering contemporary art on a new and elevated level. -

Bibliography RACKSTRAW DOWNES Reviews and Publications 2006

Bibliography RACKSTRAW DOWNES Reviews and Publications 2006 “Rackstraw Downes,” Hanging Loose, Vol. 89, ill. Front/back cover, pp. 65-72 2005 Yezzi, David. “A conversation with Rackstraw Downes,” The New Criterion, December, pp. 48-52 Schwartz, Sanford; Storr, Robert, and Downes, Rackstraw. “Rackstraw Downes,” Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ. April 2005, 200 pp. 100 color pl., 50 halftones Kernan, Nathan. “Rackstraw Downes at Betty Cuningham,” Artnews, February Wilkin, Karen. “MoMA Plus,” The Hudson Review, Winter 2005, Vol.LVII, No. 4 2004 Vanderbilt, Tom. “Best of 2004, 13 Critics and Curators Look at the Year in Art,” Artforum, December, pp. 170, 171 Mac Adam, Alfred. Reviews “Rackstraw Downes, Betty Cuningham,” Art News, December, p. 137 Panero, James. “Gallery Chronicle,” The New Criterion, November, p. 43 Smith, Roberta. Art in Review “Rackstraw Downes,” The New York Times, October 22 Schjeldahl, Peter. The Art World “True Views, Rackstraw Downes’s Realism,” The New Yorker, October 18, p. 208 “Fixed Gaze,” The New York Observer, October 18 Levin. Voice Choices: ‘Rackstraw Downes,” Village Voice, October 13-19 Cohen, David. Arts & Letters “A Chat with the Painter, Abstract Empiricism, Rackstraw Downes on Landsapes, Interiors & Why To Not Always Listen to Your Mother,” The New York Sun, September 30 Bui, Phong. “Rackstraw Downes in Conversation with Phong Bui,” The Brooklyn Rail, September, pp. 24, 25 Long, Jim. “To Look Like Seeing,” exhibition catalogue, Betty Cuningham Gallery, New York, September, pp. 3 – 7 Mullarkey, Maureen. Review, New York Sun, June 3 2003 Johnson, Ken. “Realism, Admittedly Slippery, Explores What Can and Can’t Be Seen,” New York Times, December 19 2002 Johnson, Ken. -

Rackstraw Downes Infrastructures

RackstRaw Downes Infrastructures Rackstraw Downes: The Mouth of the Passagassawaukeag at Belfast, ME, Seen from the Frozen Foods Plant, 1989, 3 1 BY STEPHEN MAINE oil on two-part canvas, 36 ⁄8 by 84 ⁄4 inches. Private collection. Courtesy Parrish Art Museum, Southampton, N.Y. Since taking up landScape painting in the early 1970s, and underneath features of the industrialized american land- that vision is inextricably linked to vantage point, as was demon- Rackstraw downes has devised and refined a quirky brand scape, both urban and rural. english-born and now dividing his strated in “Rackstraw downes: Onsite paintings, 1972-2008,” recent- of realism in which close attention to visual fact vies with an time between new York and texas, downes has segued from a ly at the parrish art Museum, Southampton, n.Y. in his graphite CuRReNtlY ON View idiosyncratic conception of pictorial space. Juggling fidelity to pastoral mode of depiction to one that is narrative, repor- drawings, oil sketches and finished paintings, downes works exclu- “Rackstraw Downes: under the the ever-changing appearance of the world, truth to his own torial, akin to documentation. three recent exhibitions have sively in the presence of his subject (whether en plein air or indoors), westside Highway” at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Ridgefield, perception of those appearances, and loyalty to the formal provided a superb opportunity to come to grips with the scope endeavoring to render reality in a manner true to how he observes it Conn., through Jan. 2, 2011. exigencies of his paintings’ design, the artist, over time, has of downes’s achievement, his working methods and the linear as he scans the scene.