Report: Election 2020 Political Violence Data and Trends

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

January 6, 2011

August 31, 2021 Robert S. LaBrant 12411 Pine Ridge Drive Perry, MI 48872 Dear Mr. LaBrant: The Michigan Department of State (Department) acknowledges receipt of your letter dated June 28, 2021, which requests the issuance of a declaratory ruling or interpretative statement regarding the Department’s interpretation of the Michigan Campaign Finance Act, MCL 169.201, et seq. Your request seeks answers to the following six questions: (1) Whether a political party committee, as defined in MCL 169.211(6) may maintain an administrative fund, which may accept funding and make disbursements that fall outside the regulatory scope of the MCFA, i.e., issue ads that do not expressly advocate the nomination and election of a candidate? See MCL 169.206 (2)(j). (2) Whether such a political party committee administrative fund is a “person” for the purposes of MCL 169.211(2) and may make contributions to a ballot question committee as defined in MCL 169.202(3)? (3) Whether a political party committee administrative fund which receives or expends $500.00 or more in a calendar year, for the “qualification, passage, or defeat of a ballot question,” is required to register itself as a ballot question committee as required by MCL 169.224 and file disclosure statements as required by MCL 169.234? (4) Whether a state central political party committee administrative fund may make disbursements to a county or district political party committee administrative fund paying or reimbursing them for ballot question petition circulation? (5) Whether a state central, county -

Testimony of Robert J

Government of the District of Columbia Metropolitan Police Department Testimony of Robert J. Contee, III Acting Chief of Police Capitol Complex Security Failures on January 6, 2021 United States House of Representatives Committee on Appropriations Honorable Rosa L. DeLauro, Chairwoman Honorable Kay Granger, Ranking Member January 26, 2021 U.S. House of Representatives Virtual Briefing Washington, D.C. Good morning, Chairwoman DeLauro, Ranking Member Granger, and members of the Committee. I am Robert J. Contee, III, the Acting Chief of Police of the Metropolitan Police Department of the District of Columbia, the primary police force in the District of Columbia. I appreciate this opportunity to brief you on the events of January 6, 2021, a dark day for our country. It is critically important that we – members of Congress, District leaders and policy makers, D.C. residents, and all Americans – find answers to questions about the 6th. I will relate to you the facts as we know them at this time, based on the point of view of MPD and the government of the District of Columbia. As with any event with multiple agencies, thousands of people, and almost as many cameras as people, there will inevitably be several perspectives and possibly inconsistencies that will need to be aligned as we gather more information. That process has been understandably delayed by the massive security operations around the 59th Presidential Inauguration, but certainly will be a focus for all involved agencies in the months to come. Mayor Muriel Bowser and the Metropolitan Police Department take pride in protecting all groups, regardless of their beliefs, who come to the nation’s capital to exercise their First Amendment rights “peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”1 The Metropolitan Police Department is a recognized leader in protecting and supporting these peaceful assemblies. -

Early Dance Division Calendar 17-18

Early Dance Division 2017-2018 Session 1 September 9 – November 3 Monday Classes Tuesday Classes September 11 Class September 12 Class September 18 Class September 19 Class September 25 Class September 26 Class October 2 Class October 3 Class October 9 Class October 10 Class October 16 Class October 17 Class October 23 Class October 24 Class October 30 Last Class October 31 Last Class Wednesday Classes Thursday Classes September 13 Class September 14 Class September 20 Class September 21* Class September 27 Class September 28 Class October 4 Class October 5 Class October 11 Class October 12 Class October 18 Class October 19 Class October 25 Class October 26 Class November 1 Last Class November 2 Last Class Saturday Classes Sunday Classes September 9 Class September 10 Class September 16 Class September 17 Class September 23 Class September 24 Class September 30* Class October 1 Class October 7 Class October 8 Class October 14 Class October 15 Class October 21 Class October 22 Class October 28 Last Class October 29 Last Class *Absences due to the holiday will be granted an additional make-up class. Early Dance Division 2017-2018 Session 2 November 4 – January 22 Monday Classes Tuesday Classes November 6 Class November 7 Class November 13 Class November 14 Class November 20 No Class November 21 No Class November 27 Class November 28 Class December 4 Class December 5 Class December 11 Class December 12 Class December 18 Class December 19 Class December 25 No Class December 26 No Class January 1 No Class January 2 No Class January 8 Class -

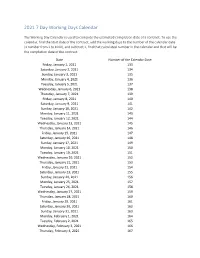

2021 7 Day Working Days Calendar

2021 7 Day Working Days Calendar The Working Day Calendar is used to compute the estimated completion date of a contract. To use the calendar, find the start date of the contract, add the working days to the number of the calendar date (a number from 1 to 1000), and subtract 1, find that calculated number in the calendar and that will be the completion date of the contract Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, January 1, 2021 133 Saturday, January 2, 2021 134 Sunday, January 3, 2021 135 Monday, January 4, 2021 136 Tuesday, January 5, 2021 137 Wednesday, January 6, 2021 138 Thursday, January 7, 2021 139 Friday, January 8, 2021 140 Saturday, January 9, 2021 141 Sunday, January 10, 2021 142 Monday, January 11, 2021 143 Tuesday, January 12, 2021 144 Wednesday, January 13, 2021 145 Thursday, January 14, 2021 146 Friday, January 15, 2021 147 Saturday, January 16, 2021 148 Sunday, January 17, 2021 149 Monday, January 18, 2021 150 Tuesday, January 19, 2021 151 Wednesday, January 20, 2021 152 Thursday, January 21, 2021 153 Friday, January 22, 2021 154 Saturday, January 23, 2021 155 Sunday, January 24, 2021 156 Monday, January 25, 2021 157 Tuesday, January 26, 2021 158 Wednesday, January 27, 2021 159 Thursday, January 28, 2021 160 Friday, January 29, 2021 161 Saturday, January 30, 2021 162 Sunday, January 31, 2021 163 Monday, February 1, 2021 164 Tuesday, February 2, 2021 165 Wednesday, February 3, 2021 166 Thursday, February 4, 2021 167 Date Number of the Calendar Date Friday, February 5, 2021 168 Saturday, February 6, 2021 169 Sunday, February -

January 13, 2021 / Rules and Regulations

2744 Federal Register / Vol. 86, No. 8 / Wednesday, January 13, 2021 / Rules and Regulations DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE G. Executive Order 13777, Enforcing the List of Nationwide Permits Included in Regulatory Reform Agenda This Rule and General Conditions Department of the Army, Corps of H. Executive Order 13921, Promoting Nationwide Permits (NWPs) Engineers American Seafood Competitiveness and Economic Growth 12. Oil or Natural Gas Pipeline Activities I. 2018 Legislative Outline for Rebuilding 21. Surface Coal Mining Activities 33 CFR Chapter II 29. Residential Developments Infrastructure in America [Docket Number: COE–2020–0002] 39. Commercial and Institutional II. Discussion of Public Comments Developments RIN 0710–AA84 A. Overview 40. Agricultural Activities B. Responses to General Comments 42. Recreational Facilities Reissuance and Modification of C. Comments on Proposed Actions Under 43. Stormwater Management Facilities Nationwide Permits Executive Order 13921, Promoting 44. Mining Activities American Seafood Competitiveness and 48. Commercial Shellfish Mariculture AGENCY: Army Corps of Engineers, DoD. Economic Growth Activities ACTION: Final rule. D. Comments on the 2018 Legislative 50. Underground Coal Mining Activities Outline for Rebuilding Infrastructure in 51. Land-Based Renewable Energy SUMMARY: Nationwide Permits (NWPs) America Generation Facilities authorize certain activities under E. Comments on Regional Conditioning of 52. Water-Based Renewable Energy Generation Pilot Projects Section 404 of the Clean Water Act and Nationwide Permits 55. Seaweed Mariculture Activities Section 10 of the Rivers and Harbors Act F. Comments on Proposed Removal of the of 1899. The NWPs help protect the 56. Finfish Mariculture Activities 300 Linear Foot Limit for Losses of 57. Electric Utility Line and aquatic environment and the public Stream Bed Telecommunications Activities interest by providing incentives to G. -

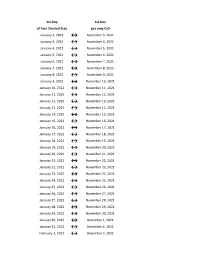

Flex Dates.Xlsx

1st Day 1st Day of Your Desired Stay you may Call January 2, 2022 ↔ November 3, 2021 January 3, 2022 ↔ November 4, 2021 January 4, 2022 ↔ November 5, 2021 January 5, 2022 ↔ November 6, 2021 January 6, 2022 ↔ November 7, 2021 January 7, 2022 ↔ November 8, 2021 January 8, 2022 ↔ November 9, 2021 January 9, 2022 ↔ November 10, 2021 January 10, 2022 ↔ November 11, 2021 January 11, 2022 ↔ November 12, 2021 January 12, 2022 ↔ November 13, 2021 January 13, 2022 ↔ November 14, 2021 January 14, 2022 ↔ November 15, 2021 January 15, 2022 ↔ November 16, 2021 January 16, 2022 ↔ November 17, 2021 January 17, 2022 ↔ November 18, 2021 January 18, 2022 ↔ November 19, 2021 January 19, 2022 ↔ November 20, 2021 January 20, 2022 ↔ November 21, 2021 January 21, 2022 ↔ November 22, 2021 January 22, 2022 ↔ November 23, 2021 January 23, 2022 ↔ November 24, 2021 January 24, 2022 ↔ November 25, 2021 January 25, 2022 ↔ November 26, 2021 January 26, 2022 ↔ November 27, 2021 January 27, 2022 ↔ November 28, 2021 January 28, 2022 ↔ November 29, 2021 January 29, 2022 ↔ November 30, 2021 January 30, 2022 ↔ December 1, 2021 January 31, 2022 ↔ December 2, 2021 February 1, 2022 ↔ December 3, 2021 1st Day 1st Day of Your Desired Stay you may Call February 2, 2022 ↔ December 4, 2021 February 3, 2022 ↔ December 5, 2021 February 4, 2022 ↔ December 6, 2021 February 5, 2022 ↔ December 7, 2021 February 6, 2022 ↔ December 8, 2021 February 7, 2022 ↔ December 9, 2021 February 8, 2022 ↔ December 10, 2021 February 9, 2022 ↔ December 11, 2021 February 10, 2022 ↔ December 12, 2021 February -

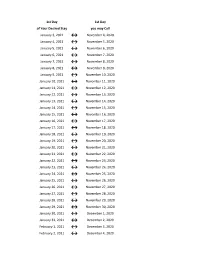

Flex Dates.Xlsx

1st Day 1st Day of Your Desired Stay you may Call January 3, 2021 ↔ November 4, 2020 January 4, 2021 ↔ November 5, 2020 January 5, 2021 ↔ November 6, 2020 January 6, 2021 ↔ November 7, 2020 January 7, 2021 ↔ November 8, 2020 January 8, 2021 ↔ November 9, 2020 January 9, 2021 ↔ November 10, 2020 January 10, 2021 ↔ November 11, 2020 January 11, 2021 ↔ November 12, 2020 January 12, 2021 ↔ November 13, 2020 January 13, 2021 ↔ November 14, 2020 January 14, 2021 ↔ November 15, 2020 January 15, 2021 ↔ November 16, 2020 January 16, 2021 ↔ November 17, 2020 January 17, 2021 ↔ November 18, 2020 January 18, 2021 ↔ November 19, 2020 January 19, 2021 ↔ November 20, 2020 January 20, 2021 ↔ November 21, 2020 January 21, 2021 ↔ November 22, 2020 January 22, 2021 ↔ November 23, 2020 January 23, 2021 ↔ November 24, 2020 January 24, 2021 ↔ November 25, 2020 January 25, 2021 ↔ November 26, 2020 January 26, 2021 ↔ November 27, 2020 January 27, 2021 ↔ November 28, 2020 January 28, 2021 ↔ November 29, 2020 January 29, 2021 ↔ November 30, 2020 January 30, 2021 ↔ December 1, 2020 January 31, 2021 ↔ December 2, 2020 February 1, 2021 ↔ December 3, 2020 February 2, 2021 ↔ December 4, 2020 1st Day 1st Day of Your Desired Stay you may Call February 3, 2021 ↔ December 5, 2020 February 4, 2021 ↔ December 6, 2020 February 5, 2021 ↔ December 7, 2020 February 6, 2021 ↔ December 8, 2020 February 7, 2021 ↔ December 9, 2020 February 8, 2021 ↔ December 10, 2020 February 9, 2021 ↔ December 11, 2020 February 10, 2021 ↔ December 12, 2020 February 11, 2021 ↔ December 13, 2020 -

Contingent Election of the President and Vice President by Congress: Perspectives and Contemporary Analysis

Contingent Election of the President and Vice President by Congress: Perspectives and Contemporary Analysis Updated October 6, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R40504 Contingent Election of the President and Vice President by Congress Summary The 12th Amendment to the Constitution requires that presidential and vice presidential candidates gain “a majority of the whole number of Electors appointed” in order to win election. With a total of 538 electors representing the 50 states and the District of Columbia, 270 electoral votes is the “magic number,” the arithmetic majority necessary to win the presidency. What would happen if no candidate won a majority of electoral votes? In these circumstances, the 12th Amendment also provides that the House of Representatives would elect the President, and the Senate would elect the Vice President, in a procedure known as “contingent election.” Contingent election has been implemented twice in the nation’s history under the 12th Amendment: first, to elect the President in 1825, and second, the Vice President in 1837. In a contingent election, the House would choose among the three candidates who received the most electoral votes. Each state, regardless of population, casts a single vote for President in a contingent election. Representatives of states with two or more Representatives would therefore need to conduct an internal poll within their state delegation to decide which candidate would receive the state’s single vote. A majority of state votes, 26 or more, is required to elect, and the House must vote “immediately” and “by ballot.” Additional precedents exist from 1825, but they would not be binding on the House in a contemporary election. -

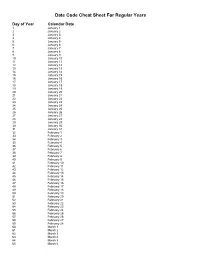

Julian Date Cheat Sheet for Regular Years

Date Code Cheat Sheet For Regular Years Day of Year Calendar Date 1 January 1 2 January 2 3 January 3 4 January 4 5 January 5 6 January 6 7 January 7 8 January 8 9 January 9 10 January 10 11 January 11 12 January 12 13 January 13 14 January 14 15 January 15 16 January 16 17 January 17 18 January 18 19 January 19 20 January 20 21 January 21 22 January 22 23 January 23 24 January 24 25 January 25 26 January 26 27 January 27 28 January 28 29 January 29 30 January 30 31 January 31 32 February 1 33 February 2 34 February 3 35 February 4 36 February 5 37 February 6 38 February 7 39 February 8 40 February 9 41 February 10 42 February 11 43 February 12 44 February 13 45 February 14 46 February 15 47 February 16 48 February 17 49 February 18 50 February 19 51 February 20 52 February 21 53 February 22 54 February 23 55 February 24 56 February 25 57 February 26 58 February 27 59 February 28 60 March 1 61 March 2 62 March 3 63 March 4 64 March 5 65 March 6 66 March 7 67 March 8 68 March 9 69 March 10 70 March 11 71 March 12 72 March 13 73 March 14 74 March 15 75 March 16 76 March 17 77 March 18 78 March 19 79 March 20 80 March 21 81 March 22 82 March 23 83 March 24 84 March 25 85 March 26 86 March 27 87 March 28 88 March 29 89 March 30 90 March 31 91 April 1 92 April 2 93 April 3 94 April 4 95 April 5 96 April 6 97 April 7 98 April 8 99 April 9 100 April 10 101 April 11 102 April 12 103 April 13 104 April 14 105 April 15 106 April 16 107 April 17 108 April 18 109 April 19 110 April 20 111 April 21 112 April 22 113 April 23 114 April 24 115 April -

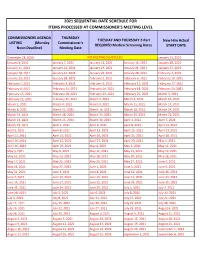

2021 Sequential Date List

2021 SEQUENTIAL DATE SCHEDULE FOR ITEMS PROCESSED AT COMMISSIONER'S MEETING LEVEL COMMISSIONERS AGENDA THURSDAY TUESDAY AND THURSDAY 2-Part New Hire Actual LISTING (Monday Commissioner's REQUIRED Medical Screening Dates START DATE Noon Deadline) Meeting Date December 28, 2020 NO MEETING SCHEDULED January 13, 2021 January 4, 2021 January 7, 2021 January 12, 2021 January 14, 2021 January 20, 2021 January 11, 2021 January 14, 2021 January 19, 2021 January 21, 2021 January 27, 2021 January 18, 2021 January 21, 2021 January 26, 2021 January 28, 2021 February 3, 2021 January 25, 2021 January 28, 2021 February 2, 2021 February 4, 2021 February 10, 2021 February 1, 2021 February 4, 2021 February 9, 2021 February 11, 2021 February 17, 2021 February 8, 2021 February 11, 2021 February 16, 2021 February 18, 2021 February 24, 2021 February 15, 2021 February 18, 2021 February 23, 2021 February 25, 2021 March 3, 2021 February 22, 2021 February 25, 2021 March 2, 2021 March 4, 2021 March 10, 2021 March 1, 2021 March 4, 2021 March 9, 2021 March 11, 2021 March 17, 2021 March 8, 2021 March 11, 2021 March 16, 2021 March 18, 2021 March 24, 2021 March 15, 2021 March 18, 2021 March 23, 2021 March 25, 2021 March 31, 2021 March 22, 2021 March 25, 2021 March 30, 2021 April 1, 2021 April 7, 2021 March 29, 2021 April 1, 2021 April 6, 2021 April 8, 2021 April 14, 2021 April 5, 2021 April 8, 2021 April 13, 2021 April 15, 2021 April 21, 2021 April 12, 2021 April 15, 2021 April 20, 2021 April 22, 2021 April 28, 2021 April 19, 2021 April 22, 2021 April 27, 2021 April -

Pay Date Calendar

Pay Date Information Select the pay period start date that coincides with your first day of employment. Pay Period Pay Period Begins (Sunday) Pay Period Ends (Saturday) Official Pay Date (Thursday)* 1 January 10, 2016 January 23, 2016 February 4, 2016 2 January 24, 2016 February 6, 2016 February 18, 2016 3 February 7, 2016 February 20, 2016 March 3, 2016 4 February 21, 2016 March 5, 2016 March 17, 2016 5 March 6, 2016 March 19, 2016 March 31, 2016 6 March 20, 2016 April 2, 2016 April 14, 2016 7 April 3, 2016 April 16, 2016 April 28, 2016 8 April 17, 2016 April 30, 2016 May 12, 2016 9 May 1, 2016 May 14, 2016 May 26, 2016 10 May 15, 2016 May 28, 2016 June 9, 2016 11 May 29, 2016 June 11, 2016 June 23, 2016 12 June 12, 2016 June 25, 2016 July 7, 2016 13 June 26, 2016 July 9, 2016 July 21, 2016 14 July 10, 2016 July 23, 2016 August 4, 2016 15 July 24, 2016 August 6, 2016 August 18, 2016 16 August 7, 2016 August 20, 2016 September 1, 2016 17 August 21, 2016 September 3, 2016 September 15, 2016 18 September 4, 2016 September 17, 2016 September 29, 2016 19 September 18, 2016 October 1, 2016 October 13, 2016 20 October 2, 2016 October 15, 2016 October 27, 2016 21 October 16, 2016 October 29, 2016 November 10, 2016 22 October 30, 2016 November 12, 2016 November 24, 2016 23 November 13, 2016 November 26, 2016 December 8, 2016 24 November 27, 2016 December 10, 2016 December 22, 2016 25 December 11, 2016 December 24, 2016 January 5, 2017 26 December 25, 2016 January 7, 2017 January 19, 2017 1 January 8, 2017 January 21, 2017 February 2, 2017 2 January -

Presidential Documents 421 Presidential Documents

Federal Register / Vol. 86, No. 3 / Wednesday, January 6, 2021 / Presidential Documents 421 Presidential Documents Executive Order 13970 of December 31, 2020 Adjustments of Certain Rates of Pay By the authority vested in me as President by the Constitution and the laws of the United States of America, it is hereby ordered as follows: Section 1. Statutory Pay Systems. The rates of basic pay or salaries of the statutory pay systems (as defined in 5 U.S.C. 5302(1)), as adjusted under 5 U.S.C. 5303, are set forth on the schedules attached hereto and made a part hereof: (a) The General Schedule (5 U.S.C. 5332(a)) at Schedule 1; (b) The Foreign Service Schedule (22 U.S.C. 3963) at Schedule 2; and (c) The schedules for the Veterans Health Administration of the Department of Veterans Affairs (38 U.S.C. 7306, 7404; section 301(a) of Public Law 102–40) at Schedule 3. Sec. 2. Senior Executive Service. The ranges of rates of basic pay for senior executives in the Senior Executive Service, as established pursuant to 5 U.S.C. 5382, are set forth on Schedule 4 attached hereto and made a part hereof. Sec. 3. Certain Executive, Legislative, and Judicial Salaries. The rates of basic pay or salaries for the following offices and positions are set forth on the schedules attached hereto and made a part hereof: (a) The Executive Schedule (5 U.S.C. 5312–5318) at Schedule 5; (b) The Vice President (3 U.S.C. 104) and the Congress (2 U.S.C.