Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016 Lilly Report of Political Financial Support

16 2016 Lilly Report of Political Financial Support 1 16 2016 Lilly Report of Political Financial Support Lilly employees are dedicated to innovation and the discovery of medicines to help people live longer, healthier and more active lives, and more importantly, doing their work with integrity. LillyPAC was established to work to ensure that this vision is also shared by lawmakers, who make policy decisions that impact our company and the patients we serve. In a new political environment where policies can change with a “tweet,” we must be even more vigilant about supporting those who believe in our story, and our PAC is an effective way to support those who share our views. We also want to ensure that you know the story of LillyPAC. Transparency is an important element of our integrity promise, and so we are pleased to share this 2016 LillyPAC annual report with you. LillyPAC raised $949,267 through the generous, voluntary contributions of 3,682 Lilly employees in 2016. Those contributions allowed LillyPAC to invest in 187 federal candidates and more than 500 state candidates who understand the importance of what we do. You will find a full financial accounting in the following pages, as well as complete lists of candidates and political committees that received LillyPAC support and the permissible corporate contributions made by the company. In addition, this report is a helpful guide to understanding how our PAC operates and makes its contribution decisions. On behalf of the LillyPAC Governing Board, I want to thank everyone who has made the decision to support this vital program. -

Nebraska Farm Bureau Board Sets 2020 Agriculture Policy Priorities

www.nefb.org FEBRUARY/MARCH 2020 | VOL. 38 | ISSUE 1 FARM BUREAU NEWS 4 Trade Victories NEFB-PAC Friends 6 of Agriculture SWEET SIXTEEN YF&R Conference LEADERSHIP FINALIST 9 Success ACADEMY PAGE 8 INSIDE 10 Teacher of the Year PAGE 5 Nebraska Farm Bureau board sets 2020 agriculture policy priorities he Nebraska Farm Bureau Board of Directors has set the organization’s public policy priorities for 2020. Nebraska Farm Bureau’s state policy Nebraska Farm Bureau’s national policy TEach year the Board identifies priorities to guide the priority list for 2020 includes: priority list for 2020 includes: organization in its efforts to support Nebraska’s farm and l Reducing Nebraska’s overreliance on l Continuing to promote and work to expand international ranch families. property taxes and seeking a more markets for Nebraska agricultural products. “There are many issues that impact our farms and balanced system to fund education. l Ensuring federal regulations and federal programs work ranches. It’s no secret that when agriculture does well, our l Growing Nebraska’s livestock sector for farm and ranch families including: rural communities thrive, and our entire state benefits. To and value-added agriculture. l Appropriate allocation of federal assistance to expand that end, it’s imperative we focus on the areas where we l Expanding farm and ranch access broadband access in rural areas; can do the most good in helping our members be success- to high-quality broadband service l Protecting farmers’ access to modern farming technology, ful,” said Steve Nelson, Nebraska Farm Bureau president. statewide. veterinary medications and crop protection tools; Every policy issue Farm Bureau works on is connected in l Proactive engagement on both state l Proper implementation of renewable energy mandates; some way to helping members keep their operations viable water quality and quantity issues. -

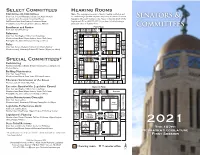

Senators & Committees

Select Committees Hearing Rooms Committee on Committees Note: The ongoing replacement of Capitol heating, ventilation and Chair: Sen. Robert Hilkemann; V. Chair: Sen. Adam Morfeld air conditioning equipment requires temporary relocation of certain Senators & 1st District: Sens. Bostelman, Kolterman, Moser legislative offices and hearing rooms. Please contact the Clerk of the 2nd District: Sens. Hunt, Lathrop, Lindstrom, Vargas Legislature’sN Office (402-471-2271) if you have difficulty locating a 3rd District: Sens. Albrecht, Erdman, Groene, Murman particular office or hearing1st room. Floor Enrollment and Review First Floor Committees Chair: Sen. Terrell McKinney Account- ing 1008 1004 1000 1010 Reference 1010-1000 1326-1315 Chair: Sen. Dan Hughes; V. Chair: Sen. Tony Vargas M Fiscal Analyst H M 1012 W 1007 1003 W Members: Sens. Geist, Hilgers, Lathrop, Lowe, McCollister, 1015 Pansing Brooks, Slama, Stinner (nonvoting ex officio) 1402 1401 1016 Rules 1017 1308 1404 1403 1401-1406 1019 1301-1314 1023-1012 Chair: Sen. Robert Clements; V. Chair: Sen. Wendy DeBoer 1305 1018 Security Research 1306 Members: Sens. J. Cavanaugh, Erdman, M. Hansen, Hilgers (ex officio) 1405 1021 1406 Pictures of Governors 1022 Research H H Gift 1302 1023 15281524 1522 E E 1510 Shop Pictures of Legislators Info. 1529-1522 Desk 1512-1502 H E E H Special Committees* 1529 1525 1523 1507 1101 Redistricting 1104 Members: Sens. Blood, Briese, Brewer, Geist, Lathrop, Linehan, Lowe, W Bill Room Morfeld, Wayne 1103 Cafeteria Mail-Copy 1114-1101 1207-1224 Building Maintenance Center 1417-1424 1110 Self- 1107 Service Chair: Sen. Steve Erdman Copies Members: Sens. Brandt, Dorn, Lowe, McDonnell, Stinner W H W M 1113 1115 1117 1423 M 1114 Education Commission of the States 1113-1126 1200-1210 1212 N Members: Sens. -

FY 2019 Political Contributions.Xlsx

WalgreenCoPAC Political Contributions: FY 2019 Recipient Amount Arkansas WOMACK FOR CONGRESS COMMITTEE 1,000.00 Arizona BRADLEY FOR ARIZONA 2018 200.00 COMMITTE TO ELECT ROBERT MEZA FOR STATE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 200.00 ELECT MICHELLE UDALL 200.00 FRIENDS OF WARREN PETERSEN 200.00 GALLEGO FOR ARIZONA 1,000.00 JAY LAWRENCE FOR THE HOUSE 18 200.00 KATE BROPHY MCGEE FOR AZ 200.00 NANCY BARTO FOR HOUSE 2018 200.00 REGINA E. COBB 2018 200.00 SHOPE FOR HOUSE 200.00 VINCE LEACH FOR SENATE 200.00 VOTE HEATHER CARTER SENATE 200.00 VOTE MESNARD 200.00 WENINGER FOR AZ HOUSE 200.00 California AMI BERA FOR CONGRESS 4,000.00 KAREN BASS FOR CONGRESS 3,500.00 KEVIN MCCARTHY FOR CONGRESS 5,000.00 SCOTT PETERS FOR CONGRESS 1,000.00 TONY CARDENAS FOR CONGRESS 1,000.00 WALTERS FOR CONGRESS 1,000.00 Colorado CHRIS KENNEDY BACKPAC 400.00 COFFMAN FOR CONGRESS 2018 1,000.00 CORY GARDNER FOR SENATE 5,000.00 DANEYA ESGAR LEADERSHIP FUND 400.00 STEVE FENBERG LEADERSHIP FUND 400.00 Connecticut LARSON FOR CONGRESS 1,000.00 Delaware CARPER FOR SENATE 1,000.00 Florida BILIRAKIS FOR CONGRESS 1,000.00 DARREN SOTO FOR CONGRESS 1,000.00 DONNA SHALALA FOR CONGRESS 1,000.00 STEPHANIE MURPHY FOR CONGRESS 1,000.00 VERN BUCHANAN FOR CONGRESS 2,500.00 Georgia BUDDY CARTER FOR CONGRESS 4,000.00 Illinois 1 WalgreenCoPAC Political Contributions: FY 2019 Recipient Amount CHUY GARCIA FOR CONGRESS 1,000.00 CITIZENS FOR RUSH 1,000.00 DAN LIPINSKI FOR CONGRESS 1,000.00 DAVIS FOR CONGRESS/FRIENDS OF DAVIS 1,500.00 FRIENDS OF CHERI BUSTOS 1,000.00 FRIENDS OF DICK DURBIN COMMITTEE -

April 26-29, 2021

UNICAMERAL UPDATE News published daily at Update.Legislature.ne.gov Vol. 44, Issue 17 / April 26 - 29, 2021 Corporate tax cut, Tax credit for private school other revenue measures advanced scholarship contributions, fter two days of discussion, child care stalls lawmakers gave first-round bill that A approval April 27 to a bill that would create includes several tax-related proposals, A a tax credit including a cut to Nebraska’s top scholarship program corporate income tax rate. for private school The Revenue Committee intro- students stalled on duced LB432 as a placeholder bill. A general file April 28 committee amendment would have after a failed cloture replaced it with the provisions of five motion. other bills heard by the committee LB364, intro- this session. duced by Elkhorn Omaha Sen. John Cavanaugh made Sen. Lou Ann a motion to divide the question and Linehan, would al- consider the various provisions as sepa- low individuals, rate amendments. The motion carried. passthrough entities, One amendment, adopted 30-7, estates, trusts and contained the provisions of LB680, corporations to claim introduced by Sen. Lou Ann Linehan a nonrefundable in- of Elkhorn. They would cut the state’s come tax credit of top corporate income tax rate to 6.84 up to 50 percent of percent — the same as the state’s top their state income individual income tax rate — begin- tax liability on con- ning Jan. 1, 2022. tributions they make Sen. Lou Ann Linehan said the proposed tax credit would incentiv- Corporations currently pay a state to nonprofit orga- ize donations to scholarship granting organizations, increasing the income tax rate of 5.58 percent on the nizations that grant number of low-income students who could attend private school. -

Revenue Hearing January 24, 2019

Transcript Prepared by Clerk of the Legislature Transcribers Office Revenue Committee January 24, 2019 LINEHAN: Welcome to the Revenue Committee public hearing. My name is Lou Ann Linehan. I'm from Elkhorn, Nebraska, and represent District 39, Legislative District 39, and serve as Chair of this committee. The committee will take up bills in the order posted. Our hearing today is your public part of the legislative process. This is your opportunity to express your position on the proposed legislation before us today. If you are unable to attend the public hearing and would like your position stated for the record, you must submit your written testimony by 5:00 p.m. the day prior to the hearings. Letters received after the cutoff will not be read into the record. No exceptions. To better facilitate today's proceeding, I ask that you provide by the following procedures. I'm gonna do this myself. Please turn off your cell phones and other electronic devices. And I want to emphasize this because it, I tried to say it yesterday but it didn't seem to work. If you want to testify on the bill that's up, move to the front so we have some-- because these go long and we want you all to have an opportunity speak. So if you're going to testify, please move forward. The order of the testimony is introducer, proponents, opponents, and neutral and closing remarks. If you will be testifying, please complete the green form and hand it to the committee clerk when you come up to testify. -

2017-Year-End-Political-Report.Pdf

1 Verizon Political Activity January – December 2017 A Message from Craig Silliman Verizon is affected by a wide variety of government policies -- from telecommunications regulation to taxation to health care and more -- that have an enormous impact on the business climate in which we operate. We owe it to our shareowners, employees and customers to advocate public policies that will enable us to compete fairly and freely in the marketplace. Political contributions are one way we support the democratic electoral process and participate in the policy dialogue. Our employees have established political action committees at the federal level and in 18 states. These political action committees (PACs) allow employees to pool their resources to support candidates for office who generally support the public policies our employees advocate. This report lists all PAC contributions, corporate political contributions, support for ballot initiatives and independent expenditures made by Verizon and its affiliates during 2017. The contribution process is overseen by the Corporate Governance and Policy Committee of our Board of Directors, which receives a comprehensive report and briefing on these activities at least annually. We intend to update this voluntary disclosure twice a year and publish it on our corporate website. We believe this transparency with respect to our political spending is in keeping with our commitment to good corporate governance and a further sign of our responsiveness to the interests of our shareowners. Craig L. Silliman Executive Vice President, Public Policy and General Counsel 2 Verizon Political Activity January – December 2017 Political Contributions Policy: Our Voice in the Democratic Process What are the Verizon Political Action Committees? including the setting of monetary contribution limitations and The Verizon Political Action Committees (PACs) exist to help the establishment of periodic reporting requirements. -

Session Review 2017 Volume XL, No

THE 105TH NEBRASKA LEGISLATURE FIRST SESSION Unicameral Update Session Review 2017 Volume XL, No. 21 2017 Session Review Contents Agriculture .......................................................................................... 1 Appropriations .................................................................................... 2 Banking, Commerce and Insurance .................................................. 4 Business and Labor ........................................................................... 6 Education ............................................................................................ 8 Executive Board ............................................................................... 11 General Affairs .................................................................................. 12 Government, Military and Veterans Affairs ...................................... 13 Health and Human Services ............................................................ 16 Judiciary ........................................................................................... 20 Natural Resources ............................................................................ 24 Retirement Systems ......................................................................... 26 Revenue ............................................................................................ 27 Transportation and Telecommunications ........................................ 30 Urban Affairs .................................................................................... -

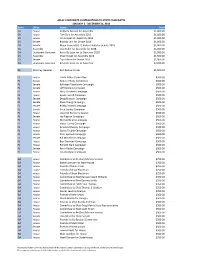

State Office Name Total CA House Anthony Rendon for Assembly

AFLAC CORPORATE CONTRIBUTIONS TO STATE CANDIDATES JANUARY 1 - DECEMBER 31, 2016 State Office Name Total CA House Anthony Rendon for Assembly $1,000.00 CA House Tom Daly for Assembly 2016 $1,000.00 CA House Jim Cooper for Assembly 2016 $1,000.00 CA Senate Ricardo Lara for Senate 2016 $1,000.00 CA Senate Major General (RET) Richard Roth for Senate 2016 $1,000.00 CA Assembly Jean Fuller for Assembly for 2018 $1,000.00 CA Lieutenant Governor Kevin De Leon for Lt. Governor 2018 $1,000.00 CA Assembly Chad Mayes for Assembly 2016 $1,500.00 CA Senate Toni Atkins for Senate 2016 $1,500.00 CA Lieutenant Governor Kevin De Leon for Lt. Governor $2,000.00 DC Attorney General Karl Racine for AG $1,500.00 FL House Frank Artiles Committee $500.00 FL Senate Anitere Flores Committee $500.00 FL Senate Kathleen Passidomo Campaign $500.00 FL Senate Jeff Clemens Campaign $500.00 FL House Holly Raschein Campaign $500.00 FL House Gayle Harrell Campaign $500.00 FL Senate Doug Broxson Campaign $500.00 FL Senate Dana Young Campaign $500.00 FL Senate Bobby Powell Campaign $500.00 FL Senate Greg Steube Campaign $500.00 FL House Jeanette Nunez Campaign $500.00 FL Senate Joe Negron Campaign $500.00 FL House Michael Bileca Campaign $500.00 FL House Victor Torres Campaign $500.00 FL House Amanda Murphy Campaign $500.00 FL House Carols Trujilio Campaign $500.00 FL House Chris Sprowls Campaign $500.00 FL Senate Bill Montford Campaign $500.00 FL House Ben Diamond Campaign $500.00 FL House Richard Stark Campaign $500.00 FL Senate Kevin Rader Campaign $500.00 FL House Jim Waldman Campaign $500.00 GA House Committee to Re-Elect Michele Henson $250.00 GA House Eddie Lumsden for State House $250.00 GA House Friends of David Casas $250.00 GA House Friends of Shaw Blackmon $250.00 GA House Friends of Shaw Blackmon $250.00 GA House Committee to Elect Earnest Coach Williams $350.00 GA House Committee to Elect Earnest Smith $350.00 GA House Committee to Elect Erica Thomas $350.00 GA House Committee to Elect Thomas S. -

2020 Contributions

State Candidate Names Committee Amount Party Office District CA Holmes, Jim Jim Holmes for Supervisor 2020 $ 700 O County Supervisor 3 CA Uhler, Kirk Uhler for Supervisor 2020 $ 500 O County Supervisor 4 CA Gonzalez, Lena Lena Gonzalez for Senate 2020 $ 1,500 D STATE SENATE 33 CA Lee, John John Lee for City Council 2020 - Primary $ 800 O City Council 12 CA Simmons, Les Simmons for City Council 2020 $ 1,000 D City Council 8 CA Porada, Debra Porada for City Council 2020 $ 500 O City Council AL CA California Manufacturers & Technology Association Political Action Committee $ 5,000 CA Desmond, Richard Rich Desmond for Supervisor 2020 $ 1,200 R County Supervisor 3 CA Hewitt, Jeffrey Jeffrey Hewitt for Board of Supervisors Riverside County 2018 $ 1,200 O County Supervisor 5 CA Gustafson, Cindy Elect Cindy Gustafson Placer County Supervisor, District 5 - 2020 $ 700 O County Supervisor 5 CA Cook, Paul Paul Cook for Supervisor 2020 $ 1,000 R County Supervisor 1 CA Flores, Dan Dan Flores for Supervisor 2020 $ 500 County Supervisor 5 CA California Taxpayers Association - Protect Taxpayers Rights $ 800,000 CA Latinas Lead California $ 500 CA Wapner, Alan Wapner for Council $ 1,000 City Council CA Portantino, Anthony Portantino for Senate 2020 $ 2,000 D STATE SENATE 25 CA Burke, Autumn Autumn Burke for Assembly 2020 $ 2,000 D STATE HOUSE 62 CA California Republican Party - State Account $ 15,000 R CA Fong, Vince Vince Fong for Assembly 2020 $ 1,500 D STATE HOUSE 34 CA O'Donnell, Patrick O'Donnell for Assembly 2020 $ 4,700 D STATE HOUSE 70 CA Sacramento Metropolitan Chamber Political Action Committee $ 2,500 CA Patterson, Jim Patterson for Assembly 2020 $ 1,500 R STATE HOUSE 23 CA Arambula, Joaquin Dr. -

![[LB737 LB771 LB778 LB857] the Committee on Education Met at 1](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4384/lb737-lb771-lb778-lb857-the-committee-on-education-met-at-1-2734384.webp)

[LB737 LB771 LB778 LB857] the Committee on Education Met at 1

Transcript Prepared By the Clerk of the Legislature Transcriber's Office Education Committee January 16, 2018 [LB737 LB771 LB778 LB857] The Committee on Education met at 1:30 p.m. on Tuesday, January 16, 2018, in Room 1525 of the State Capitol, Lincoln, Nebraska, for the purpose of conducting a public hearing on LB771, LB857, LB737, and LB778. Senators present: Mike Groene, Chairperson; Rick Kolowski, Vice Chairperson; Laura Ebke; Steve Erdman; Lou Ann Linehan; Adam Morfeld; Patty Pansing Brooks; and Lynne Walz. Senators absent: None. SENATOR GROENE: Thank you for attending. We'll start the first public hearing of the Education Committee. Sorry about being late. My clock in my office is the same as that one up there and it needs a new battery. So we will start with how we will operate the committee. Welcome to the Education Committee public hearing. My name is Mike Groene from Legislative District 42. I serve as the Chair of this committee. Committee will take up the bills in the posted agenda. Our hearing today is your public part of the legislative process. This is your opportunity to express your position on the proposed legislation before us today. You are the second house of the Legislature. To better facilitate today's proceedings, I ask that you abide by the following procedures. Please turn off cell phones and other electronic devices; move to the chairs at the front of the room when you are ready to testify. The order of testimony is introducer, proponents, opponents, neutral, and closing remarks. I will leave it open that if we have an awful...we ever have legislation that has a lot of testifiers, I will leave it that we can alternate to give everybody a chance to speak and both sides can be heard. -

Pfizer Inc. Regarding Congruency of Political Contributions on Behalf of Tara Health Foundation

SANFORD J. LEWIS, ATTORNEY January 28, 2021 Via electronic mail Office of Chief Counsel Division of Corporation Finance U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission 100 F Street, N.E. Washington, D.C. 20549 Re: Shareholder Proposal to Pfizer Inc. Regarding congruency of political contributions on Behalf of Tara Health Foundation Ladies and Gentlemen: Tara Health Foundation (the “Proponent”) is beneficial owner of common stock of Pfizer Inc. (the “Company”) and has submitted a shareholder proposal (the “Proposal”) to the Company. I have been asked by the Proponent to respond to the supplemental letter dated January 25, 2021 ("Supplemental Letter") sent to the Securities and Exchange Commission by Margaret M. Madden. A copy of this response letter is being emailed concurrently to Margaret M. Madden. The Company continues to assert that the proposal is substantially implemented. In essence, the Company’s original and supplemental letters imply that under the substantial implementation doctrine as the company understands it, shareholders are not entitled to make the request of this proposal for an annual examination of congruency, but that a simple written acknowledgment that Pfizer contributions will sometimes conflict with company values is all on this topic that investors are entitled to request through a shareholder proposal. The Supplemental letter makes much of the claim that the proposal does not seek reporting on “instances of incongruency” but rather on how Pfizer’s political and electioneering expenditures aligned during the preceding year against publicly stated company values and policies.” While the company has provided a blanket disclaimer of why its contributions may sometimes be incongruent, the proposal calls for an annual assessment of congruency.