Silverleaf Whitefly Alert for Soybean Growers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arthropod Pest Management in Greenhouses and Interiorscapes E

Arthropod Pest Management in Greenhouses and Interiorscapes E-1011E-1011 OklahomaOklahoma CooperativeCooperative ExtensionExtension ServiceService DivisionDivision ofof AgriculturalAgricultural SciencesSciences andand NaturalNatural ResourcesResources OklahomaOklahoma StateState UniversityUniversity Arthropod Pest Management in Greenhouses and Interiorscapes E-1011 Eric J. Rebek Extension Entomologist/ Ornamentals and Turfgrass Specialist Michael A. Schnelle Extension Ornamentals/ Floriculture Specialist ArthropodArthropod PestPest ManagementManagement inin GreenhousesGreenhouses andand InteriorscapesInteriorscapes Insects and their relatives cause major plant ing a hand lens. damage in commercial greenhouses and interi- Aphids feed on buds, leaves, stems, and roots orscapes. Identification of key pests and an un- by inserting their long, straw-like, piercing-suck- derstanding of appropriate control measures are ing mouthparts (stylets) and withdrawing plant essential to guard against costly crop losses. With sap. Expanding leaves from damaged buds may be tightening regulations on conventional insecti- curled or twisted and attacked leaves often display cides and increasing consumer sensitivity to their chlorotic (yellow-white) speckles where cell con- use in public spaces, growers must seek effective tents have been removed. A secondary problem pest management alternatives to conventional arises from sugary honeydew excreted by aphids. chemical control. Management strategies cen- Leaves may appear shiny and become sticky from tered around -

Managing Silverleaf Whiteflies in Cotton Phillip Roberts and Mike Toews University of Georgia

Managing Silverleaf Whiteflies in Cotton Phillip Roberts and Mike Toews University of Georgia Following these guidelines, especially on a community Insecticide Use: basis, should result in better management of SLWF locally and areawide. The goal of SLWF management is to initiate control measures just prior to the period of most rapid SLWF • Destroy host crops immediately after harvest; this population development. It is critically important that includes vegetable and melon crops in the spring and initial insecticide applications are well timed. If you are cotton (timely defoliation and harvest) and other host late with the initial application control will be very crops in the fall. difficult and expensive in the long run. It is nearly impossible to regain control once the population reaches • Scout cotton on a regular basis for SLWF adults and outbreak proportions! immatures. • SLWF Threshold: Treat when 50 percent of sampled • The presence of SLWF should influence insecticide leaves (sample 5th expanded leaf below the terminal) selection and the decision to treat other pests. are infested with multiple immatures (≥5 per leaf). • Conserve beneficial insects; do not apply insecticides • Insect Growth Regulators (Knack and Courier): use of for ANY pests unless thresholds are exceeded. IGRs are the backbone of SLWF management • Avoid use of insecticides for other pests which are programs in cotton. Effects on SLWF populations are prone to flare SLWF. generally slow due to the life stages targeted by IGRs, however these products have long residual activity • Risk for SLWF problems: and perform very well when applied on a timely basis. • Hairy leaf > smooth leaf cotton. -

Life History of the Whitefly Predator Nephaspis Oculatus

Biological Control 23, 262–268 (2002) doi:10.1006/bcon.2001.1008, available online at http://www.idealibrary.com on Life History of the Whitefly Predator Nephaspis oculatus (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) at Six Constant Temperatures Shun-Xiang Ren,* Philip A. Stansly,† and Tong-Xian Liu‡ *Laboratory of Insect Zoology, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou 510692, People’s Republic of China; †University of Florida, Southwest Florida Research and Education Center, 2686 State Road 29, North Immokalee, Florida 34142; and ‡Texas Agricultural Experiment Station, Texas A&M University, 2415 East Highway 83, Weslaco, Texas 78596-8399 Received April 19, 2001; accepted October 20, 2001 aleurodes floridensis (Quaintance), Dialeurodes citri Nephaspis oculatus (Blatchley) is a predator of (Ashmead), and D. citrifolii (Morgan) (Muma et al., whiteflies including Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius) and 1961; Gordon, 1972, 1985; Cherry and Dowell, 1979). B. argentifolii Bellows and Perring. The usefulness of Life history parameters and consumption rates for this this and other coccinellid predators of whiteflies could ladybeetle on B. argentifolii under laboratory condi- be improved by better information on responses to tions were estimated by Liu et al. (1997) who recog- different temperatures experienced in the field. We nized its suitability for greenhouse conditions. There- reared N. oculatus from egg to adult in incubators at six constant temperatures and observed a linear rela- fore, it would be useful to understand how populations tionship between developmental time and tempera- perform within the range of temperatures found in ture for all preimaginal lifestages through all but the most growing environments, including greenhouses, highest temperatures (33°C). Four larval instars were where the beetles might be used. -

Bemisia Tabaci)

The CRISPR Journal Volume 3, Number 2, 2020 ª Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. DOI: 10.1089/crispr.2019.0067 RESEARCH ARTICLE CRISPR-Cas9-Based Genome Editing in the Silverleaf Whitefly (Bemisia tabaci) Chan C. Heu,1 Francine M. McCullough,1 Junbo Luan,2,3 and Jason L. Rasgon1,4,5,* Abstract Bemisia tabaci cryptic species Middle East-Asia Minor I (MEAM1) is a serious agricultural polyphagous insect pest and vector of numerous plant viruses, causing major worldwide economic losses. B. tabaci control is limited by lack of robust gene editing tools. Gene editing is difficult in B. tabaci due to small embryos that are technically challenging to inject and which have high mortality post injection. We developed a CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing protocol based on injection of vitellogenic adult females rather than embryos (‘‘ReMOT Control’’). We identified an ovary-targeting peptide ligand (‘‘BtKV’’) that, when fused to Cas9 and injected into adult females, transduced the ribonucleoprotein complex to the germline, resulting in efficient, heritable editing of the offspring genome. In contrast to embryo injection, adult injection is easy and does not require specialized equipment. Development of easy-to-use gene editing protocols for B. tabaci will allow researchers to apply the power of reverse genetic approaches to this species and will lead to novel control methods for this devastating pest insect. Introduction The economic importance of B. tabaci demands new Bemisia tabaci cryptic species Middle East-Asia Minor I methods to control this devastating pest insect. Gene edit- (MEAM1) is a widely distributed invasive agricultural ing, using CRISPR-Cas9, has formed the foundation for pest that causes the economic loss of billions of dollars novel control strategies for insect vectors of human dis- in crop damages worldwide.1,2 B. -

Identification of Whitefly Resistance in Tomato and Hot Pepper

Identification of whitefly resistance in tomato and hot pepper Syarifin Firdaus Thesis committee Thesis supervisor Prof. dr. R.G.F. Visser Professor of Plant Breeding Wageningen University Thesis co-supervisors Dr. ir. A.W. van Heusden Senior Scientist, Wageningen UR Plant Breeding Wageningen University and Research Centre Dr. B.J. Vosman Senior Scientist, Wageningen UR Plant Breeding Wageningen University and Research Centre Other members Prof. dr. ir. L.F.M. Marcelis, Wageningen University Prof. dr. ir. A. van Huis, Wageningen University Dr. R.G. van den Berg, Wageningen University Dr. W.J. de Kogel, Plant Research International, Wageningen This research was conducted under the auspices of the Graduate School of Experimental Plant Sciences Identification of whitefly resistance in tomato and hot pepper Syarifin Firdaus Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of doctor at Wageningen University by the authority of the Rector Magnificus Prof. dr. M.J. Kropff, in the presence of the Thesis Committee appointed by the Academic Board to be defended in public on Wednesday 12 September 2012 at 13.30 p.m. in the Aula. Syarifin Firdaus Identification of whitefly resistance in tomato and hot pepper Thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, NL (2012) With references, with summaries in Dutch, English and Indonesian. ISBN: 978-94-6173-360-3 Table of Contents Chapter 1 General introduction 7 Chapter 2 The Bemisia tabaci species complex: additions from different parts of the world 25 Chapter 3 Identification of silverleaf -

Whitefly Population Dynamics in Okra Plantations

Whitefly population dynamics 1 9 Whitefly population dynamics in okra plantations Germano Leão Demolin Leite(1), Marcelo Picanço(2), Gulab Newandram Jham(3) and Márcio Dionízio Moreira(2) (1)Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Instituto de Ciências Agrárias, Caixa Postal 135, CEP 39404-006 Montes Claros, MG. E-mail: [email protected] (2)Universidade Federal de Viçosa (UFV), Dep. de Biologia animal, CEP 36571-000 Viçosa, MG. E-mail: [email protected] (3)UFV, Dep. de Química. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract – The control of whitefly Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius) biotype B (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) on okra (Abelmoschus esculentus L.) consists primarily in the use of insecticides, due to the lack of information on other mortality factors. The objective of this study was to evaluate the spatial and temporal population dynamics of the whitefly B. tabaci biotype B on two successive A. esculentus var. “Santa Cruz” plantations. Leaf chemical composition, leaf nitrogen and potassium contents, trichome density, canopy height, plant age, predators, parasitoids, total rainfall and median temperature were evaluated and their relationships with whitefly on okra were determined. Monthly number estimates of whitefly adults, nymphs (visual inspection) and eggs (magnifying lens) occurred on bottom, middle and apical parts of 30 plants/plantation (one leaf/plant). Plants senescence and natural enemies, mainly Encarsia sp., Chrysoperla spp. and Coccinellidae, were some of the factors that most contributed to whitefly reduction. The second okra plantation, 50 m apart from the first, was strongly attacked by whitefly, probably because of the insect migration from the first to the second plantation. No significant effects of the plant canopy on whitefly eggs and adults distribution were found. -

2019-Knk-0001-1277-R

GROUP 7C INSECTICIDE FIRST AID (continued) If swallowed: Immediately call a poison control center or doctor. Do not induce vomiting unless told to do so by a poison control center or doctor. Do not give any liquid to the person. Do not give anything by mouth to an unconscious person. If inhaled: Move person to fresh air. If person is not breathing, call 911 or an ambulance, then give arti- ficial respiration, preferably by mouth-to-mouth, if possible. Active Ingredient By Wt Call a poison control center or doc- *Pyriproxyfen ��������������������������������������������������� 11.23% tor for further treatment advice. Other Ingredients . 88.77% HOT LINE NUMBER Total 100.00% Have the product container or label with you when *2-[1-methyl-2-(4-phenoxyphenoxy)ethoxy]pyridine calling a poison control center or doctor, or going Contains 0.86 pound ai per gallon. for treatment. You may also contact 800-892-0099 Contains aromatic petroleum distillates. for emergency medical treatment information. EPA Reg. No. 59639-95 NOTE TO PHYSICIANS EPA Est. 39578-TX-1 If ingested, probable mucosal damage may con- traindicate the use of gastric lavage. This prod- KEEP OUT OF REACH OF CHILDREN uct contains a light hydrocarbon liquid; ingestion CAUTION or subsequent vomiting can result in aspiration of SEE BELOW FOR ADDITIONAL this product, which can cause pneumonitis. PRECAUTIONARY STATEMENTS. PRECAUTIONARY STATEMENTS PERSONAL PROTECTIVE EQUIPMENT (PPE): HAZARDS TO HUMANS & DOMESTIC ANIMALS Applicators and other handlers must wear: cover- CAUTION alls over short-sleeved shirt and short pants or long- sleeved shirt and long pants, chemical-resistant Causes skin and eye irritation. -

Silverleaf Whitefly Management

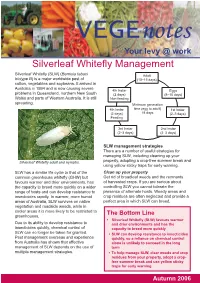

VEGEnotes Your levy @ work Silverleaf Whitefl y Management Silverleaf Whitefl y (SLW) (Bemisia tabaci Adult biotype B) is a major worldwide pest of (10–15 days) cotton, vegetables and soybeans. It arrived in Australia in 1994 and is now causing severe 4th Instar Eggs problems in Queensland, northern New South (2 days) (8–10 days) Wales and parts of Western Australia. It is still Non-feeding spreading. Minimum generation 4th Instar time (egg to adult) 1st Instar (2 days) 18 days (2–3 days) Feeding 3rd Instar 2nd Instar (2–3 days) (2–3 days) SLW management strategies There are a number of useful strategies for managing SLW, including cleaning up your Silverleaf Whitefl y adult and nymphs. property, adopting a crop-free summer break and using yellow sticky traps for early warning. SLW has a similar life cycle to that of the Clean up your property common greenhouse whitefl y (GHW) but Get rid of broadleaf weeds and the remnants favours warmer and drier environments, has of harvested crops. If you are serious about the capacity to breed more quickly on a wider controlling SLW you cannot tolerate the range of hosts and can develop resistance to presence of alternate hosts. Weedy areas and insecticides rapidly. In warmer, more humid crop residues are often neglected and provide a areas of Australia, SLW survives on native perfect area in which SLW can breed. vegetation and roadside weeds, while in cooler areas it is more likely to be restricted to The Bottom Line greenhouses. • Silverleaf Whitefl y (SLW) favours warmer Due to its ability to develop resistance to and drier environments and has the insecticides quickly, chemical control of capacity to breed more quickly SLW can no longer be taken for granted. -

A New Whitefly Pest Has Recently Become a Potential Threat to Floral and Other Crops in the U.S

THE Q BIOTYPE OF BEMISIA TABACI IN THE U.S. AND MANAGEMENT SUGGESTIONS John Sanderson, Dept. of Entomology, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY Daniel Gilrein, Cornell Cooperative Extension of Suffolk County, LIHREC, Riverhead, NY October, 2005 A new whitefly pest has recently become a potential threat to floral and other crops in the U.S. Actually, this isn’t a new species but rather a new strain of the familiar silverleaf whitefly. It has been confirmed in poinsettia, gerbera and veronica in at least six states to date (10/05). The following explains the situation and its implications. First, a bit of whitefly history: the familiar and native greenhouse whitefly, Trialeurodes vaporariorum, has been a pest since the early days of U.S. greenhouse production. Around 1987, the sweetpotato whitefly, Bemisia tabaci, was found on poinsettias and outdoor crops. Although it has been known in the US for around 100 years, these outbreaks were determined to be from a new biotype (B- biotype) which in 1994 was renamed the “silverleaf whitefly,” B. argentifolii. In 1995, the registration of imidacloprid insecticides (Marathon, Admire, etc.) enabled growers to control this new strain more easily. Since then several more very effective insecticides have been registered that also control this insect. At the end of 2004, a strain of the sweetpotato whitefly, called the Q biotype, was found in Arizona on poinsettias purchased at a retail store. Samples of this strain were identified by 3 different labs as the Q biotype, distinct from the common B biotype and thought to originate from a wholesale nursery in California. -

Strategies and Considerations for Efficient Rnai-Mediated

insects Review Debugging: Strategies and Considerations for Efficient RNAi-Mediated Control of the Whitefly Bemisia tabaci Emily A. Shelby 1, Jeanette B. Moss 1, Sharon A. Andreason 2 , Alvin M. Simmons 2, Allen J. Moore 1 and Patricia J. Moore 1,* 1 Department of Entomology, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, USA; [email protected] (E.A.S.); [email protected] (J.B.M.); [email protected] (A.J.M.) 2 U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, U.S. Vegetable laboratory, Charleston, SC 29414, USA; [email protected] (S.A.A.); [email protected] (A.M.S.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 14 September 2020; Accepted: 21 October 2020; Published: 22 October 2020 Simple Summary: The whitefly Bemisia tabaci is a crop pest insect that is difficult to control through commercially available methods. Technology that inhibits gene expression is a promising avenue for controlling whiteflies and other pests. While there are resources available to make this method insect specific, and therefore more effective, it is currently being used in a way that targets insects broadly. This broad approach can cause potential harm to the surrounding environment. Here, we discuss considerations for using gene-silencing technology as a pest management strategy for whiteflies in a way that is specific to this pest, which will address short- and long-term issues of sustainability. We also provide a way of selecting target genes based on their roles in the life history of the insect, which will reduce the potential for unintended negative consequences. Abstract: The whitefly Bemisia tabaci is a globally important pest that is difficult to control through insecticides, transgenic crops, and natural enemies. -

Sweetpotato Whitefly (Order: Hemiptera, Family: Aleyrodidae, Bemisia Tabaci Or Argentifolii - Silverleaf)

Sweetpotato whitefly (Order: Hemiptera, Family: Aleyrodidae, Bemisia tabaci or argentifolii - silverleaf) Description: Adult: The adult is small, about 0.9 to 1.2 mm in length and holds its solid white wings roof-like over a pale yellow body while at rest. Immature stages: Immature stages begin with a pointed oblong yellow egg (0.2 mm) which darkens at the apex just before hatching. The first instar or crawler stage (0.2-0.3 mm) settles down on the underside of leaves close to the egg shell and goes through three more molts as a Sweetpotato (silverleaf) whitefly adult. sessile, flattened oval nymph. Late third and fourth instars begin to develop eye spots and are often referred to as red-eyed nymphs. The last instar, or "pupal stage" (0.7- 0.8 mm, late instars are shown in the photo), has very distinct eye spots. Biology: Life cycle: The life cycle from egg to adult may be 18 days under warm temperatures (86oF) but may take as long as 2 months under cool conditions. The number of eggs produced is also greater in warm weather than in cool weather. The rate of reproduction ranges from 50 Whitefly nymphs or “scales” under leaf. to 400 eggs (avg. 160, of which about two-thirds are female) per generation, hence a high capacity for reproduction. Seasonal distribution: In Georgia, whiteflies are generally not an economic problem in the spring growing season, unless the production is in an infested greenhouse. In the late summer and fall, whitefly numbers increase dramatically in some years. Damage to Crop: In tomato, the main damage caused by whitefly results from the transmission of plant viruses (geminivirus) which cause a severe stunting of the tomato plant and a drastic reduction in yield. -

Cassava Whitefly, Bemisia Tabaci (Gennadius) (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) in East African Farming Landscapes: a Review of the Factors Determining Abundance

Bulletin of Entomological Research (2018) 108, 565–582 doi:10.1017/S0007485318000032 © Cambridge University Press 2018. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Cassava whitefly, Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius) (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) in East African farming landscapes: a review of the factors determining abundance S. Macfadyen1*, C. Paull2, L.M. Boykin3, P. De Barro2, M.N. Maruthi4, M. Otim5, A. Kalyebi5,6, D.G. Vassão7, P. Sseruwagi6,W.T.Tay2, H. Delatte8, Z. Seguni6, J. Colvin4 and C.A. Omongo5 1CSIRO, Clunies Ross St. Acton, ACT, 2601, Australia: 2CSIRO, Boggo Rd. Dutton Park, QLD, 4001, Australia: 3University of Western Australia, School of Molecular Sciences, 35 Stirling Highway, Crawley, WA 6009, Australia: 4Natural Resources Institute, University of Greenwich, Chatham Maritime, Kent, ME4 4TB, UK: 5National Crops Resources Research Institute, Kampala, Uganda: 6Mikocheni Agricultural Research Institute, P.O. Box 6226 Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: 7Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology, Hans-Knoell Str. 8 D-07745 Jena, Germany: 8CIRAD, UMR PVBMT, Saint Pierre, La Réunion 97410-F, France Abstract Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius) (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) is a pest species complex that causes widespread damage to cassava, a staple food crop for millions of households in East Africa. Species in the complex cause direct feeding damage to cassava and are the vectors of multiple plant viruses. Whilst significant work has gone into developing virus-resistant cassava cultivars, there has been little research effort aimed at under- standing the ecology of these insect vectors.