How Sustainable Enterprises Develop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Environmental Report 2013/2014

Annual Environmental Report 2013/2014 Board for Energy & Environment November 2014 Contents STATEMENT....................................................................................................................3 KEY PERFORMANCE INDICATORS................................................................................3 ENVIRONMENTAL OBJECTIVES ....................................................................................4 QUALITY ASSURANCE ...................................................................................................5 GOVERNANCE.................................................................................................................5 SCOPE OF REPORTING.....................................................................................................5 ISO 14001 ....................................................................................................................6 OTHER REPORTING..........................................................................................................6 BASE YEAR RECALCULATION POLICY...................................................................................6 CARBON AND ENERGY .................................................................................................7 WATER, EMISSIONS AND DISCHARGES.......................................................................8 WASTE AND RECYCLING...............................................................................................9 TRAVEL .........................................................................................................................10 -

Aircraft Electrification

Aircraft electrification The future of aerospace starts with Cranfield The relationship between aviation and the environment is one of the key challenges facing developed societies. Major reductions in carbon emissions are required to meet environmental targets. Aviation emissions are increasing by around 5% a year and the EU’s Flightpath 2050 programme calls for a 75% reduction in carbon emissions per passenger kilometre by 2050. Aircraft electrification is a necessary step towards achieving those goals and tackling climate change. As the only university in Europe with its own airport, aircraft and air navigation service provider, Cranfield offers a unique spectrum of relevant capabilities, expertise and facilities for the development of aircraft electrification and the aviation ecosystem. This includes the relevant approvals to design, build and fly a whole new aircraft concept. This is integral to achieving urban air mobility. Challenges in electrification include thermal management, systems design for integration into the airframe, battery management, power-to-weight ratios, testing, reliability and certification of new aircraft technology. Aircraft electrification will not Aircraft vehicle design page 4 succeed without parallel development Aircraft propulsion page 6 in airport infrastructure, power supply and distribution, and assessment of the Unmanned aerial systems technology page 8 impact of aviation on the environment. With Cranfield’s global Relevant technologies – batteries, energy storage, research airport and airside solar power farm, our £67 million Digital Aviation Research and Technology Centre (DARTeC), and electric motors and generators page 10 our fully instrumented autonomous vehicle test road (MUEAVI) Relevant technologies – materials technology and alongside the airport perimeter, we provide a testbed for this additive manufacturing for aircraft electrification page 12 transformative future technology. -

Credit for Learning

THE L IFELONG L EARNING N ETWORK FOR THE EAST OF ENGLAND Credit for Learning A Guide to the Accreditation of Prior Certificated and Experiential Learning in Higher Education in the East of England Part of the Regional Credit Agreement Mick Betts and Brenda Crichton January 2009 M O V E IMPACT M O V E IMPACT M O V E IMPACT M O V E IMPACT M O V E IMPACT M O V E IMPACT M O V E IMPACT M O V E IMPACT M O V E IMPACT M O V E IMPACT IMPACT M O V E IMPACT M O V E IMPACT M O V E IMPACT M O V E I M PA C T MOVE IMPACT M O V E IMPACT M O V E IMPACT M O V E IMPACT M O V E I M PA C T MOVE M O V E IMPACT M O V E IMPACT M O V E IMPACT M O V E IMPACT M O V E IMPACT M O V E IMPACT M O V E IMPACT M O V E IMPACT M O V E IMPACT M O V E IMPACT Mission Statement MOVE’s overarching purpose is to bring about a step change in progression opportunities for vocational learners across the East of England region and to improve opportunities into and through Higher Education at both undergraduate and postgraduate levels. M O V E IMPACT M O V E IMPACT M O V E IMPACT M O V E IMPACT M O V E IMPACT IMPACT M O V E IMPACT M O V E IMPACT M O V E IMPACT M O V E I M PA C T MOVE M O V E IMPACT M O V E IMPACT M O V E IMPACT M O V E IMPACT M O V E IMPACT Foreword The accreditation of prior and experiential learning is a powerful and effective way of recognising, accrediting and re-purposing existing learning. -

REF 2021 Code of Practice

REF 2021 Code of Practice Research & Innovation Office June 2019 Table of Contents Part 1: Introduction .................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Context ............................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Institutional policies and strategies to support equality and diversity ................................ 3 1.3 Update on Actions Taken Since REF 2014 ...................................................................... 4 1.4 Transparency, Consistency, Accountability and Inclusivity .............................................. 8 Part 2: Identifying staff with significant responsibility for research ........................................... 10 Part 3: Determining research independence ........................................................................... 11 3.1 Policies and Procedures ................................................................................................ 11 3.2 Staff, Committees and Training ..................................................................................... 14 3.3 Appeals ......................................................................................................................... 20 3.4 Equality Impact Assessment .......................................................................................... 21 Part 4: Selection of outputs .................................................................................................. -

The EUCAMS Gear Partnership – a Model of Industry/Academic Collaboration

The Eighth International Conference on Condition Monitoring and Machinery Failure Prevention Technologies The EUCAMS gear partnership – a model of industry/academic collaboration Andrew Starr Cranfield University, MK43 0AL, UK 01234 758374 [email protected] Muhammad Khan Department of Mechanical Engineering, Universiti Teknologi Petronas Bandar Seri Iskandar, 31750 Tronoh, Perak, Malaysia Brian Allen, Mick Marshall, Albert Phang QinetiQ, Cody Technology Park, Building A7 G070, Farnborough, Hampshire, GU14 0LX, UK Nuri Badi, Yong Kang Chen School of Engineering and Technology, University of Hertfordshire Hatfield, Herts. AL10 9AB, UK Rodger Edwards, Jyoti Sinha, Pawel Rzeszucinski School of MACE, University of Manchester, Oxford Road M13 9PL UK Rhys Jones, Ken Mao School of Engineering, Warwick University, Coventry, CV4 7AL UK Duncan Shepherd Ventech Systems, UK Alan Curran Materials Integrity Group, L002, RAF Wyton, Huntingdon, Cambridgeshire, PE28 2EA Abstract Challenges in maintenance systems can pose multi-faceted problems, which are difficult to resolve alone. Over a four year period, a partnership evolved a vision for tackling the understanding of fundamentally difficult mechanical failures and their detection, with potential for practical exploitation of the solutions. The partnership assembled a team of researchers and far-sighted project management, to undertake a study of gearbox failures, including finite element modelling, gear testing, and signal analysis. The partnership trained a series of doctoral and postdoctoral staff in running an integrated project, coping with changes in staffing and locations. The final stages of the work will validate the models and signal processing. The Eighth International Conference on Condition Monitoring and Machinery Failure Prevention Technologies 1. Introduction This paper is about how partnerships help solve problems, and it is illustrated with an integrated case study in gear damage detection. -

Global Study of 48 Cities Finds Nature Sanitizes 41.7 Million Tons of Human Waste a Year 19 February 2021

Global study of 48 cities finds nature sanitizes 41.7 million tons of human waste a year 19 February 2021 may allow adaptive design and management, reducing costs, and improving effectiveness and sustainability, and safeguard the continued existence of these areas of land." Wastewater treatment infrastructure that converts human feces into harmless products is an important tool for global human health. However, more than 25% of the world's population did not have access to basic sanitation facilities in 2017 and another 14% used toilets in which waste was disposed of onsite. While some of this waste may be hazardous to local populations, previous research has suggested that natural wetlands and mangroves, for example, provide effective treatment services. Part of a sewage treatment plant (Hyderabad, India), The Navikubo wetland in Uganda processes which relies on biological processes as a key part of the untreated wastewater from more than 100,000 sanitation process. Credit: Simon Wilcock households, protecting the Murchison Bay and Lake Victoria from harmful contaminants, while in the United States coastal wetlands in the Gulf of Mexico remove nitrogen from the Mississippi River. The first global-scale assessment of the role ecosystems play in providing sanitation finds that nature provides at least 18% of sanitation services in 48 cities worldwide, according to researchers in the United Kingdom and India. The study, published February 19 in the journal One Earth, estimates that more than 2 million cubic meters of the cities' human waste is processed each year without engineered infrastructure. This includes pit latrine waste that gradually filters through the soil—a natural process that cleans it before it reaches groundwater. -

Oxford Cambridge Arc Universities Group

OXFORD CAMBRIDGE ARC UNIVERSITIES GROUP We wholeheartedly support the Government’s strategy for investment across the Oxford-Cambridge Arc and recognise its significance as a driver for economic growth in a region of national strategic importance. As the Arc Universities Group, we commit to working together with business and government, and with one another, to foster research, skills and innovation, in order to further unleash potential for growth and prosperity. SIGNED BY: Professor Nick Braisby Bill Rammell Buckinghamshire New University University of Bedfordshire Professor Alistair Fitt Professor Louise Richardson Oxford Brookes University University of Oxford Professor Sir Peter Gregson Sir Anthony Seldon Cranfield University The University of Buckingham Professor Mary Kellett Professor Stephen Toope The Open University University of Cambridge Professor Nick Petford Professor Roderick Watkins University of Northampton Anglia Ruskin University Vice-Chancellors of the ten universities in the Oxford – Cambridge Arc 12 UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE ARC UNIVERSITIES GROUP 2 UNIVERSITY OF UNIVERSITY NORTHAMPTON OF CAMBRIDGE ANGLIA RUSKIN UNIVERSITY UNIVERSITY OF BEDFORDSHIRE CRANFIELD UNIVERSITY THE OPEN UNIVERSITY THE UNIVERSITY OF BUCKINGHAM TEN UNIVERSITIES ONE FUTURE ARC UNIVERSITIES GROUP OXFORD BROOKES UNIVERSITY UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD BUCKINGHAMSHIRE NEW UNIVERSITY GENERATING £5bn £13bn COMBINED TURNOVER FOR THE ECONOMY Leading the way OXFORD UNIVERSITY in global innovation OF CAMBRIDGE CAMBRIDGE Underpinning UK ARC UNIVERSITIES GROUP competitiveness -

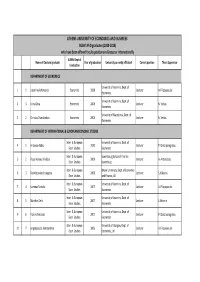

AUEB's Phd Graduates

ATHENS UNIVERSITY OF ECONOMICS AND BUSINESS AUEB's PhD graduates (2000‐2010) who have been offered faculty positions in Greece or internationally AUEB's Dept of Name of Doctoral graduate Year of graduation University currently affiliated Current position Thesis Supervisor Graduation DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS University of Ioannina, Dept. of 1 1 Lapatinas Athanasios Economics 2008 Lecturer A. Filippopoulos Economics University of Ioannina, Dept. of 2 3 Krina Griva Economics 2004 Lecturer N. Vettas Economics University of Macedonia, Dept. of 3 2 Christou Charalambos Economics 2004 Lecturer N. Vettas Economics DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL & EUROPEAN ECONOMIC STUDIES Inter. & European Univeristy of Ioannina, Dept. of 4 1 Antoniou Fabio 2010 Lecturer P. Chatzipanagiotou Econ. Studies Economics Inter. & European Luxembourg School of Finance, 5 2 Papanikolaou Nikolaos 2009 Lecturer A. Antzoulatos Econ. Studies Luxemburg Inter. & European Brunel University, Dept. of Economics 6 3 Dioikitopoulos Evangelos 2008 Lecturer S. Kalyvitis Econ. Studies and Finance, UK Inter. & European University of Ioannina, Dept. of 7 4 Kammas Pantelis 2007 Lecturer A. Filippopoulos Econ. Studies Economics Inter. & European University of Ioannina, Dept. of 8 5 Manthos Delis 2007 Lecturer S. Brisimis Econ. Studies Economics Inter. & European University of Ioannina, Dept. of 9 6 Tsakiris Nikolaos 2007 Lecturer P. Chatzipanagiotou Econ. Studies Economics Inter. & European University of Glasgow, Dept. of 10 7 Angelopoulos Konstantinos 2006 Lecturer A. Filippopoulos Econ. Studies Economics, UK Inter. & European University of Ioannina, Dept. of 11 8 Adam Antonis 2005 Lecturer T. Moutos Econ. Studies Economics Inter. & European 12 9 Arvanitis Stilianos 2004 AUEB, Dept. of Economics Assistant Professor A. Demos Econ. Studies Inter. & European 13 10 Filippaios Fragkiskos 2004 University of Kent, UK Senior Lecturer M. -

Cranfield Campus

A B C D E F 251 191 To Pilot Hall and 237 Sewage Works Fedden 1 House 1 Chicheley 1-12 Brook Handley Page Close 2 2-12 Royce Road IA IA 1 Reynolds Close 22 IA 21 18 IA Henson Clos CMDC 20 1-14 (Conference 19 28 entrance) 1 IA IA 2 1-12a 19-24 st Road IA IA IA IA 240 Cherry Trees e We East Road Nursery BYH3 Mitchell Road 13-18 Duncan Road 17 IA The Loxham 227 Observatory 228 Squash courts To Bedford 11-12 and Newport New student Stringfellow 235 Catering store 1-16a accommodation Hall 226 IA Pagnell 2 233a 2 coming 2021 BYH2 BYH4 7-10 229 CMDC 234 MUGA 225 Mitchell I9 239 (Residential 233 IA entrance) 3-6 Hall IA 13-18 Duncan Road BYH1 Baroness 20 21 19 231 I9 Young Hall Prince Phillip 86 Pre-school Mitchell Road-30 232 23 11 230 IAIA Mitchell Road IA CH3 The Crescent Chilver 9 1-2 IAIA Hall 1a BYH5 Avenue 1-4 2-8 1 College Road The Green 1-8 IA LH9 The Drive 49 IA IA IA CH2 N 34 243 IA IA Tennis courts U 36 I9 £ 24 LH8 Tennis courts IA 111 I9 I 122 LH6 26 IA IA 146 I9 LH5 Main Reception 33 65 IA IA 32 LH4 IA IA å 3 LH13 Lanchester Road 38 B3a IA â CMRI LH10 LH11 Design and Print 3 LH12 IA á 39 3 LH14 37 31 58 Lanchester â Electric 19 vehicle charging Hall â LH16 Sports IA â Avenue 85 LH15 IA Hall â 45 I9 LH7 â 41 57 61 30 Stafford Central StaffordCripps Cripps 125 Education Services IA 88 To M1 (North) J14 and Student Advice Centre H" å 29 79 å 56 â 62 70 40 53 42 90 55 IA Kings IA 63 Norton IT Library 115 y Wa 84 82 I9 £ N University University 114 I Avenue CentralI9 IA 43b 4 43 52a 4 Vincent Building 43a 110 83 172 Avenue 52 IMEC Key -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 09 December 2020 Version of attached le: Published Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Bucknall, Clive and Altst¤adt,Volker and Auhl, Dietmar and Buckley, Paul and Dijkstra, Dirk and Galeski, Andrzej and G¤ogelein,Christoph and Handge, Ulrich A. and He, Jiasong and Liu, Chen-Yang and Michler, Goerg and Piorkowska, Ewa and Slouf, Miroslav and Vittorias, Iakovos and Wu, Jun Jie (2020) 'Structure, processing and performance of ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene (IUPAC Technical Report). Part 1 : characterizing molecular weight.', Pure and applied chemistry., 92 (9). pp. 1469-1483. Further information on publisher's website: https://doi.org/10.1515/pac-2019-0405 Publisher's copyright statement: c 2020 IUPAC De Gruyter. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For more information, please visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk Pure Appl. -

Conducting a Practice-Based Study in a Novel Context: Methodological Challenges

Conducting a practice-based study in a novel context: methodological challenges Angela Bond Cranfield University, School of Management, UK University of Hertfordshire, Hertfordshire Business School, UK [email protected], [email protected] Dr Colin Pilbeam Cranfield University, School of Management, UK [email protected] Dr Neil Turner Cranfield University, School of Management, UK [email protected] Abstract The methodological issue addressed in this paper is how to conduct a practice-based study in a novel context. We present and build on Korica, Nicolini and Johnson's (2015) proposal to explore managerial work from a practice perspective, and to understand the implications of temporary organisation for management practice (Bakker et al., 2016). We present an argument for using Schatzki’s (2002) site ontology and summarise the key features that are relevant to, and being applied in, a current empirical study. Using the study as an illustration we discuss the methodological implications of a practice-based study and conclude with recommendations for research. Word count: 6,438 Key words: social practice; site ontology; managerial work; temporary organisation Conducting a practice-based study in a novel context: methodological challenges Introduction Practice-based approaches have contributed to a number of organisation and management fields, such as knowledge and learning (Corradi, Gherardi and Verzelloni, 2010), strategy (Whittington, 2006), technology use (Orlikowski, 2007), leadership (Raelin, 2011) and projects (O’Leary and Williams, 2013). The majority of studies are conducted from knowledge and learning or strategy perspectives (Erden, Schneider and von Krogh, 2014). Guidance is available to researchers adopting practice-based approaches in empirical studies, generally (Gherardi, 2012; Nicolini, 2013), and from within specific disciplines such as strategy (Golsorkhi et al., 2015; Johnson et al., 2007) and leadership (Raelin, 2016). -

Article Processing Charges Paid by 25 UK Universities in 2014

Lawson, S 2015 Article Processing Charges Paid by 25 UK Universities in 2014. Journal of Open Humanities Data, 1: e2, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/johd.2 DATA PAPER Article Processing Charges Paid by 25 UK Universities in 2014 Stuart Lawson1 1 Research Analyst, Jisc Collections, GB Doctoral Researcher, Birkbeck, University of London, GB [email protected] This dataset contains details of 6,943 article processing charges (APCs) paid by 25 higher education institutions in the UK during 2014. The data was collected as part of Jisc Collections’ APC data collection project and has been released with permission from the institutions who provided the data. The data has been aggregated, normalized, and archived as a single CSV file. It will be of interest to those seeking to understand the scale of open access payments within the UK, and could be reused by combining it with subscription and APC expenditure data from other sources. Keywords: library services; research publications; research outputs; data Funding statement: This dataset was created as part of the author’s employment at Jisc Collections. (1) Overview for payments made in 2014. 22 of those institutions Context (listed under ‘Dataset creators’) agreed to participate Article processing charges (APCs) are fees which are some- and release their data openly. One institution agreed to time paid in order to make a research article, or other provide data but not to release it openly. Three further research output, open access. In the UK many institutions institutions (Plymouth University, Durham University, and now spend significant amounts on APCs, particularly in Loughborough University) were also asked to provide data light of the policies of RCUK and the Wellcome Trust which in order to increase the size of the dataset.