Presidential Address, 1994

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grafton Way (On Surfaced Road) Four of the Optional Walks Featured 5 Mile Walk Into Paulerspury

Northampton Northampton Grafton Way (on surfaced road) Four of the optional walks featured 5 mile walk into Paulerspury. bench 5 mile walk from Castlethorpe N N WAY alongside the Gra on Way are covered O GRAFTON WAY T F Yardley Gobion along the in greater detail with full route A R Optional walk (on surfaced road) 11 mile circular walk taking in G descriptions in the Walk, Eat & Drink Shutlanger Grand Union Canal. is 13 mile route follows the Grand Union Canal guides for South Northamptonshire: splendid views and passing towpath and then takes to undulating farmland 5 Distance (miles) from southern terminus GRAFTON WAy East South Towcester Racecourse. and villages. It is named a er the Dukes of A508 Kissing gate Walk 1: Towcester Town Walk Church of G Gra on who were large land-owners in the Walk 11: Yardley Gobion and along B r Long distance walks in South northamptonshire St Mary a the Grand Union Canal n southern part of the County throughout the Stile the Virgin d U Walk 12: Cosgrove via Aqueduct n eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Starts at Farmer’s gate io Central South Grafton n Wolverton, Milton Keynes (MK12 5NL), and C Walk 14: Paulespury Circular The White Hart a Regis n nishes by e Butchers Arms in Greens Norton Busy road, take extra care Paddocks Farm a e Walk, Eat & Drink guides are l (NN11 3AA). Full details are shown on OS available from South Northants Council Explorer Map 207. NO and tourist information centres. RT Greens Daventry HA MP TO N Isworth Norton ROA Caldecote D Farm G To r A ve Kingsher a 5 The Mount Grafton -

Northamptonshire Past and Present, No 64

JOURNAL OF THE NORTHAMPTONSHIRE RECORD SOCIETY WOOTTON HALL PARK, NORTHAMPTON NN4 8BQ ORTHAMPTONSHIRE CONTENTS AST AND RESENT Page NP P Number 64 (2011) 64 Number Notes and News … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 3 Eton’s First ‘Poor Scholars’: William and Thomas Stokes of Warmington, Northamptonshire (c.1425-1495) … … … … … … … … … 5 Alan Rogers Sir Christopher Hatton … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 22 Malcolm Deacon One Thing Leads to Another: Some Explorations Occasioned by Extracts from the Diaries of Anna Margaretta de Hochepied-Larpent … … … … 34 Tony Horner Enclosure, Agricultural Change and the Remaking of the Local Landscape: the Case of Lilford (Northamptonshire) … … … … 45 Briony McDonagh The Impact of the Grand Junction Canal on Four Northamptonshire Villages 1793-1850 … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 53 Margaret Hawkins On the Verge of Civil War: The Swing Riots 1830-1832 … … … … … … … 68 Sylvia Thompson The Roman Catholic Congregation in Mid-nineteenth-century Northampton … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 81 Margaret Osborne Labourers and Allotments in Nineteenth-century Northamptonshire (Part 1) … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 89 R. L. Greenall Obituary Notices … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 98 Index … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … 103 Cover illustration: Portrait of Sir Christopher Hatton as Lord Chancellor and Knight of the Garter, a copy of a somewhat mysterious original. Described as ‘in the manner of Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger’ it was presumably painted between Hatton’s accession to the Garter in 1588 and his death in 1591. The location and ownership of the original are unknown, and it was previously unrecorded by the National Portrait Gallery. It Number 64 2011 £3.50 may possibly be connected with a portrait of Hatton, formerly in the possession of Northamptonshire Record Society the Drake family at Shardeloes, Amersham, sold at Christie’s on 26 July 1957 (Lot 123) and again at Sotheby’s on 4 July 2002. -

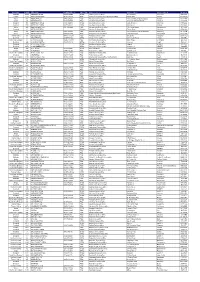

Office Address Details.Pdf

Area Name Identifier Office Name Enquiry office no. Office Type Address Line 2 Address Line 3 Address Line 4 Postcode Midlands 2244 ABBERLEY SPDO 01299 896000 SPDO Abberley Delivery Office The Common Worcester WR6 6AY London 1116 ABBEY WOOD SDO 08456 112439 PDO Abbey Wood & Thamesmead Delivery Office Nathan Way London SE28 0AW Wales 871 ABERCARN DO 01495 245025 PDO Abercarn Delivery Office Prince Of Wales Industrial Estate Newport NP11 4AA Wales 236 ABERDARE DO 01685 872007 PDO Aberdare Delivery Office Aberaman Industrial Estate Aberdare CF446ZZ Scotland 985 ABERFELDY SPDO 01887 822835 SPDO Aberfeldy Delivery Office Dunkeld Street Aberfeldy PH152AA Scotland 1785 ABERFOYLE SPDO 01877 382231 SPDO Aberfoyle Delivery Office Main Street Stirling FK8 3UG Wales 880 ABERGAVENNY DO 01873 303500 PDO Abergavenny Delivery Office 1 St. Johns Square Abergavenny NP7 5AZ Scotland 12 ABERLOUR SPDO Wayside Aberlour Delivery Office Elchies Road Aberlour AB38 9AA Wales 874 ABERTILLERY DO 01495 212546 PDO Abertillery Delivery Office Unit 5 Cwmtillery Industrial Estate Abertillery NP131XE Wales 1257 ABERYSTWYTH DO 01970 632600 PDO Glanyrafon Industrial Estate Llanbadarn Fawr Aberystwyth SY23 3GX Thames Valley 934 ABINGDON DO 08456-113-218 PDO Abingdon Delivery Office Ock Street Abingdon OX14 5AD Scotland 8 ABOYNE SPDO 08457740740 SPDO Aboyne Delivery Office Charlestown Road Aboyne AB345EJ North West England 71 ACCRINGTON DO 08456-113-070 PDO Accrington Delivery Office Infant Street Accrington BB5 1ED Scotland 995 ACHARACLE SPDO 01967 431220 SPDO Acharacle -

Playing Pitch Strategy

South Northamptonshire Council Playing Pitch Strategy December 2007 Introduction 1.1 During August 2006, South Northamptonshire Council commissioned PMP to review and update the previous countywide playing pitch strategy completed in April 2002, focusing specifically on the district. The strategy has been developed following the methodology outlined in “Towards a Level Playing Field.” 1.2 This strategy builds on the recently completed PPG17 compliant open space, sport and recreation study which considers the provision of open spaces district wide, including a range of outdoor sports facilities. The level of detail within this document provides a bespoke assessment of the supply and demand for different pitch sports and outlines specific priorities for future provision. This is particularly important in light of the population growth within the local area. 1.3 The key objectives of this playing pitch strategy are to: • analyse the current level of pitch provision, including the geographical spread and quality of pitches • assist the Council in meeting the requirements for playing pitches in accordance with the methodology developed by Sport England in conjunction with the National Playing Fields Association (NPFA) and the Central Council for Physical Recreation (CCPR) • identify the demand for pitches in the district • run the Playing Pitch Methodology (explained in detail in section five) to ascertain levels of under / over supply • identify how facilities for pitch sports can be improved to meet the needs of the community • provide strategic options and recommendations including - provision to be protected - provision to be enhanced - re-allocation of pitches - proposals for new provision Playing Pitch Strategy 1 • provide information to help the decision making process and determine future development proposals including the production of specific local standards relating to playing pitch provision. -

Ultimate Power

Ultimate Power The official magazine of the East Midlands Powerlifting Association A division of the Great Britain Powerlifting Federation September 2011 Sharn Rowlands British Senior & European Sub Junior Champion Editors View Welcome to all East Midlands powerlifters. Another 3 months has raced by and we are entering the really busy period for major international competitions with host of East Midlands lifters travelling overseas to try and bring back some glory and silverware. Congratulations to our lifters in this quarter who have achieved great success especially Jenny Hunter and Tony Cliffe for winning the British Seniors and to Jenny for also winning the European Masters and to Sharn Rowlands for becoming the British Senior Champion and the European Sub Junior Champion – tremendous achievements. It’s also good to see East Midlands lifters also featuring strongly in British Unequipped Championships – winners in the 3 lift included Jenny (again), Jackie Blasbery, Ben Cattermole, Paul Bennett and Alan Ottolangui (somehow) and in the bench press winners from the division included Ben Cattermole, Lea Meachen, Andy Howard, Paul Abbott and Matt Mackey – well done to all lifters and to those who achieved runner up positions. No letters this issue – I assume everyone must be happy with all aspects of the sport or just don’t want to commit their views to paper – it would be good as always to get any feedback about divisional, national or any issues. Thanks go to Joe Walton for another interesting training article and to George Leggett for his continuing memories – any other training tips or ideas would be welcome. -

Postmaster & the Merton Record 2020

Postmaster & The Merton Record 2020 Merton College Oxford OX1 4JD Telephone +44 (0)1865 276310 Contents www.merton.ox.ac.uk College News From the Warden ..................................................................................4 Edited by Emily Bruce, Philippa Logan, Milos Martinov, JCR News .................................................................................................8 Professor Irene Tracey (1985) MCR News .............................................................................................10 Front cover image Merton Sport .........................................................................................12 Wick Willett and Emma Ball (both 2017) in Fellows' Women’s Rowing, Men’s Rowing, Football, Squash, Hockey, Rugby, Garden, Michaelmas 2019. Photograph by John Cairns. Sports Overview, Blues & Haigh Ties Additional images (unless credited) Clubs & Societies ................................................................................24 4: © Ian Wallman History Society, Roger Bacon Society, Neave Society, Christian 13: Maria Salaru (St Antony’s, 2011) Union, Bodley Club, Mathematics Society, Quiz Society, Art Society, 22: Elina Cotterill Music Society, Poetry Society, Halsbury Society, 1980 Society, 24, 60, 128, 236: © John Cairns Tinbergen Society, Chalcenterics 40: Jessica Voicu (St Anne's, 2015) 44: © William Campbell-Gibson Interdisciplinary Groups ...................................................................40 58, 117, 118, 120, 130: Huw James Ockham Lectures, History of the Book -

21 High Street, Yardley Gobion, Northamptonshire NN12 7TN

21 High Street, Yardley Gobion, Northamptonshire NN12 7TN 21 High Street, Yardley Gobion, Northamptonshire NN12 7TN Guide Price: £870,000 A fantastic opportunity to acquire a six bedroom period equestrian property boasting paddocks, stabling and manège totalling just under three acres within striking distance of Milton Keynes and approximately 30 minutes main line railway into London Euston. Set in the sought-after village of Yardley Gobion and looking out over the village green, this deceptively spacious and charming property dates back in parts to the 1600’s and retains many original features and offers flexible family accommodation. Features • Character property • Two en-suite bedrooms • Four further bedrooms • Two family bathrooms • Sitting room with log burning stove • Dining room • Large kitchen/breakfast room • Study • Utility/boot room • Extensive gardens leading to the paddock • Annexe potential • Stables and tack room • Manège • Just under 3 acres • Ample off road parking • Energy rating E Location Yardley Gobion is a sought-after South Northamptonshire village, bypassed by the A508, approximately 3 miles north east of Stony Stratford which has varied shops, coffee shops and restaurants. The village itself has a primary school, shop, pub, restaurant, sports ground and social club. The Grand Union Canal runs nearby east of the village. There is good access to the main arterial roads including the M1 motorway and A5, with train stations at Milton Keynes and Northampton offering services to London Euston with journey times of around -

Removal of Bus Subsidies List of Affected Services

Removal of bus subsidies List of affected services: Service no Description Level of service 1 Hannington - Northampton (diversion to serve peak hour Hannington at peak times) journeys, Mon- Sat 3 Horton to Northampton (diversion to service Horton every 2 hours instead of Piddington on alternate journeys) 4N Nene Valley Call Connect (Demand Responsive Service) 0700-1900, Mon- Sat (shorter hours Sat) 4S Stamford area Call Connect (Demand Responsive Service) 0700-1900, Mon- Sat (shorter hours Sat) 9 Brambleside – Kettering every 30/60 mins, Mon-Sat 10 Daventry - Rugby (diversion to serve Barby and Kilsby) every hour, Mon- Sat 10 Mears Ashby – Northampton peak hour journeys, Mon- Sat 33 Milton Keynes – Northampton about every 2 hours, Mon-Sat 33A Milton Keynes – Northampton about every 2 hours, Mon-Sat 34 Wellingborough – Kettering about every 2 hours, Mon-Sat 35 Great Cransley – Kettering one journey per day, Tue, Thu, Fri 37 Mears Ashby – Northampton one journey per day, Mon, Wed, Sat 43 Bozeat – Northampton about every 2 hours, Mon-Sat 44 Barnwell Drive - Wellingborough (not section between every hour, Mon- Wellingborough and Irthlingborough) Sat 45 Queensway - Wellingborough (not section between every hour, Mon- Wellingborough and Irthlingborough) Sat 60 Welford – Northampton about every 2 hours, Mon-Sat 61 Coton – Northampton once per week 62 Scaldwell – Northampton twice per week 63 Norton – Northampton 3-times per week 67 Gretton - Corby - Market Harborough every 2/3 hours, Mon-Sat Northamptonshire County Council 2018-19 Budget Consultation: -

21 High Street, Yardley Gobion, Northamptonshire NN12 7TN **DRAFT**

21 High Street, Yardley Gobion, Northamptonshire NN12 7TN **DRAFT** 21 High Street, Yardley Gobion, Northamptonshire NN12 7TN Guide Price: £870,000 A fantastic opportunity to acquire a six bedroom period equestrian property boasting paddocks, stabling and manège totalling just under three acres within striking distance of Milton Keynes and approximately 30 minutes main line railway into London Euston. Set in the sought-after village of Yardley Gobion and looking out over the village green, this deceptively spacious and charming property dates back in parts to the 1600’s and retains many original features and offers flexible family accommodation. Features • Character property • Two en-suite bedrooms • Four further bedrooms • Two family bathrooms • Sitting room with log burning stove • Dining room • Large kitchen/breakfast room • Study • Utility/boot room • Extensive gardens leading to the paddock • Annexe potential • Stables and tack room • Manège • Just under 3 acres • Ample off road parking • Energy rating E Location Yardley Gobion is a sought-after South Northamptonshire village, bypassed by the A508, approximately 3 miles north east of Stony Stratford which has varied shops, coffee shops and restaurants. The village itself has a primary school, shop, pub, restaurant, sports ground and social club. The Grand Union Canal runs nearby east of the village. There is good access to the main arterial roads including the M1 motorway and A5, with train stations at Milton Keynes and Northampton offering services to London Euston with journey times -

West Northamptonshire Joint Core Strategy

Joint Position Statement (JPS) by Daventry District Council Northampton Borough Council South Northamptonshire Council on Neighbourhood Planning in West Northamptonshire 1. Introduction 1.1 This paper summarises the current position with regard to neighbourhood planning activity across West Northamptonshire and its relationship to the Joint Core Strategy. 1.2 It outlines: the name, location and status of neighbourhood development plans issues that have arisen with neighbourhood area applications and the proposed Sustainable Urban Extensions the future relationship between the Joint Core Strategy and the preparation of neighbourhood plans. 2. Neighbourhood planning activity in West Northamptonshire 2.1 The table below lists the neighbourhood development plans that have formally commenced the preparation process: District Parish/Neighbourhood Current Status (as at March 2013) Daventry Spratton Neighbourhood area application approved (Dec 2012) Daventry Moulton Neighbourhood area application approved (Dec 2012) Daventry Creaton Neighbourhood area application approved (Feb 2013 Daventry Brixworth Neighbourhood area application approved (Feb 2013 Daventry Charwelton (Forum) Neighbourhood area and forum application being determined Daventry Badby and Onley Neighbourhood area application being determined Northampton Blackthorn (Forum)* Northampton Spring Boroughs Neighbourhood area application being determined *(Forum) Northampton Wootton and East Hunsbury (with Collingtree)* Northampton Duston Parish Council South Northants Yardley Gobion * -

POST OFFICE COUNTIES ------~ PUBLICANS -Continued, Plough, J

726 POST OFFICE COUNTIES -----------------------------------------------------------------------~ PUBLICANS -continued, Plough, J. Crosswell, High street, Witney Old Angel, G. Cranwell, New Woodstock Plough, H. Croxford, Dorchester, Wallingford Old Bell, E. Wicks, Grazeley, Shinfield, Reading Plough, M. Day, East Hendred, Wantage Old Blue Bell, Mrs. F. Paul, Duke st. Henley-on-Thames Plough, T. Deeley, Lower Arncott, Ambrosden, Bicester Old Blue Man, A. Seymour, Friday street, Tbame Plough, G. Eary, Great Everdon, Daventry Old Boot, G. Lailey, Bucklebury, ReRding Plough, W. Eden borough, Bodicot, Ban bury Old Boot, J. Morris, Mears Ash by, Northampton Plough, E. Edwards, Braunston, Daventry Old Bull~ Dog, J. Salter, the Citv, Newbury Plough, A. Eeles, Finstock, Witney Old Catherine Wheel, W. Monk, Cheap street, Newbury Plough, Mrs. A. Farrow, Thatcham, Newbury Old Crown, Mrs. M. Ashby, Ashton, Towcester Plough, W. Frost, Lillingstone Lovell, Buckingham Old Crown, G. Jakeman, Weedon Plough, W. Gibbs, Stratton Audley, Bicester Old Crown, J. Riddey, Barby, Rugby Plough, J. Green, Little Coxwell, l<'aringdon Old Crown, T. Williams, Wootton, Northampton Plough, Mrs. B. Harper, Sheep street, Bicester Old Dog, T. Turk, Wood Speen east, Speen Plough, B. Herman, East Hauney, Wantage Old Duke'I Ilead, J. Brett, Deanshanger~ Stoney Stratford Plough, W. Hobson, Eastbury, Hungerford Old Fighting Cocks, R. Lord, Bridge street, Abingdon Plough, J. Hyde, Wbilton, Daventry Old Friar, J. Wallis, Twywell, Kettering Plough, W. Ilott, Alvescot, Lechlade Old George, C. Ferriman, Leafield, Witney Plough, J. Jelley, Cosgrove, Stoney Stratford Old George, G. Taylor, Bridge street, Banbury Plough, W. Jones, Noke, Oxford Old Green Man, C. Goddard, Hoe Benham, Welford Plough, T. Kenning, Wattord, Daventry Old Griffin, M1·s. -

Neighbourhood Plans South Northamptonshire Council

Neighbourhood Plans South Northamptonshire Council December 2011 1. Introduction 1.1 The Government’s Localism Act introduces new rights and powers for communities and individuals to enable them to get more involved in planning for their areas. Neighbourhood planning will allow communities to come together through a local parish council and say where they think new houses, businesses and shops should go – and what they should look like. Specifically the Act sets out proposals around community led plans (Neighbourhood Development Plans) to guide new development and in some cases granting planning permission for certain types of development. In addition the Act proposes a sub category of Neighbourhood Development Orders called Community Right to Build Orders. These will provide for community led site development. 1.2 Neighbourhood development plans could be very simple, or go into considerable detail where people want. Local communities would also be able to grant full or outline planning permission in areas where they most want to see new homes and businesses, making it easier and quicker for development to go ahead (Neighbourhood Development Orders). The Government is clear that the purpose of Neighbourhood Plans is about building neighbourhoods and not stopping growth. 1.3 Neighbourhood planning is optional but if supported by the Local Planning Authority (LPA) a Neighbourhood Plan and Orders will have weight becoming part of the plan making framework for the area and a main consideration within the planning system. The Localism Act was published in December 2010 and recently received Royal Assent. 1.4 South Northamptonshire Council and other local authorities have been starting to gear themselves up to work with Parishes and community groups on such plans.