Slate Roofing and Grading in the New Millennium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preparing for the Global Citizenship Mini Challenge

KS4 NATIONAl/FOUNDATION WELSH BaccaLAUREATE Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum Wales Preparing for the Global Citizenship Mini Challenge SOURCE PACK We can learn a lot about the issue of poverty and inequality today by studying Welsh history as well as examples from the world today. Study these sources about poverty and inequality in the slate industry in north Wales in the 19th century and the textile or clothing industry in modern Cambodia. The sources will help you to understand why workers are paid low wages, how they have protested and fought through trade unions to improve their lives and how their efforts have been opposed by those who stand to profit from the industry. If you would like to know more why not visit the National Slate Museum in Llanberis, north Wales. You can also research websites such as the Gwynedd Archives Slatesite. More can be found on the National Archives website and on the Welsh Government learning resources hwb. ISSUE: POVERTY FOCUS: INEQUALITY (cover image: Jezper/shuttersTOCK.com) (cover image: SOURCE 1: The National Wool Museum at Dre-fach Felindre, West Wales SOURCE 1: Adapted from a report in the north Wales newspaper the Daily Post, 22 June, 2013 The Great Strike at Penrhyn Slate Quarry, near Bethesda, out in protest, marking the beginning of the Great Strike, which north Wales, lasting from 1900 to 1903, was one of the largest lasted for three years. ever seen in Britain. The strikers received generous support, including a huge By 1900 Penrhyn was the world’s largest slate quarry, Christmas pudding, weighing two and a half tonnes from a worked by nearly 3,000 quarrymen. -

The Mineral Resource Maps of Wales

The Mineral Resource Maps of Wales Minerals and Waste Mineral Resources and Policy Team Geology and Landscape Wales Open Report OR/10/032 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY MINERALS AND WASTE MINERAL RESOURCES AND POLICY TEAM GEOLOGY AND LANDSCAPE WALES The National Grid and other The Mineral Resource Maps of Ordnance Survey data are used with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Wales Stationery Office. Ordnance Survey licence number Licence No:100037272/2010. Keywords A.J. Humpage and T.P. Bide Wales; Minerals, Resources, Resource Maps Front cover Taff’s Wells quarry, working Carboniferous limestone, Ffos y Fran surface mine working the Coal Measures and Barnhill quarry working Pennant sandstone. BGS © NERC Bibliographical reference HUMPAGE, A.J. and BIDE, T.P. 2010. The Mineral Resource Maps of Wales British Geological Survey Open Report, OR/10/032. 49pp. Copyright in materials derived from the British Geological Survey’s work is owned by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) and/or the authority that commissioned the work. You may not copy or adapt this publication without first obtaining permission. Contact the BGS Intellectual Property Rights Section, British Geological Survey, Keyworth, e-mail [email protected] You may quote extracts of a reasonable length without prior permission, provided a full acknowledgement is given of the source of the extract. © NERC 2010. All rights reserved Keyworth, Nottingham British Geological Survey 2010 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY The full range of Survey publications is available from the BGS British Geological Survey offices Sales Desks at Nottingham, Edinburgh and London; see contact details below or shop online at www.geologyshop.com Columbus House, Village Way, Greenmeadow Springs, The London Information Office also maintains a reference Tongwynlais, Cardiff, CF15 7NE collection of BGS publications including maps for consultation. -

Gwynedd Archives, Caernarfon Record Office

GB 0219 Penyrorsedd Gwynedd Archives, Caernarfon Record Office This catalogue was digitised by The National Archives as part of the National Register of Archives digitisation project NRA 28851 The National Archives - HAY 1988 NATION^: REGISTER OF ARCHIVES PENYRORSEDD SLATE SPARRY COMPANY RECORDS Caernarvonshiro Record Office 19 7 3 Records deposited by Penyrorsedd Slate Quarry Company Ltd. Catalogued by Mrs. M.A * Aris Senior Assistant Archivist Class Mark t Penyrorsodd INSPECTION OP THESE RECORDS IS SUBJECT TO A 30 YEAR RULE. Contents X FINANCIAL 1-7 Ledgers* 8-15 Cash books. 16-20 Other accounts. II PRODUCTION 21-28 Production account books. 29-38 Other production books. 39 - 51 Stock books. 52-58 Cost books. 59 - 70 Letting lists. 71 - 82 Analysis of costs. 83 - 89 Production and wages sheets III SALES 90 - 98 Order books, etc. 99-103 Price lists. 104 Character book. IV SLATE SHIPMENTS 105 ** 116 Cargo books. V WAGES, ETC. 117 - 150 Time books and wages books. 151 - 154 Other wages books. 155 - 160 Registers of Employees. 161 - 180 National Insurance register 181 - 185 Subsistence analysis books. 186 - 196 Analysis of pay. 197 - 200 Other wages records. VI QUARRY NOTICES 201 - 222 Quarry notices. VII ACCIDENT RECORDS 223 - 270 Accident books* notices of accidents, etc. 271 * 285 Compensation account books 286 ** 290 Other registers. VIII CORRESPONDENCE, ETC. 291 - 328 General correspondence and other papers, 329 * 330 Repairs to farms and cottages. 331 - 362 Rainfall charts. 363 - 366 Medical Club records. 367 - 374 Quarry Union Works Committee records. PLANS 375 - 423 Plans X PHOTOGRAPHS CHS.1245/1-26 Photographs X FINANCIAL 1 - 7 Ledgers! 1. -

Moelwynion & Cwm Lledr

Llanrwst Llyn Padarn Llyn Ogwen CARNEDDAU Llanberis A5 Llyn Peris B5427 Tryfan Moelwynion & Cwm Lledr A4086 Nant Peris GLYDERAU B5106 Glyder Fach Capel Curig CWM LLEDR MAP PAGE 123 Climbers’ Club Guide Glyder Fawr LLANBERIS PASS A4086 Llynnau Llugwy Mymbyr Introduction A470 Y Moelwynion page 123 The Climbers’ Club 4 Betws-y-Coed Acknowledgments 5 20 Stile Wall 123 B5113 21 Craig Fychan 123 13 Using this guidebook 6 6 Grading 7 22 Craig Wrysgan 123 Carnedd 12 Carnedd Moel-siabod 5 9 10 23 Upper Wrysgan 123 SNOWDON Crag Selector 8 Llyn Llydaw y Cribau 11 3 4 Flora & Fauna 10 24 Moel yr Hydd 123 A470 A5 Rhyd-Ddu Geology 14 25 Pinacl 123 Dolwyddelan Lledr Conwy The Slate Industry 18 26 Waterfall Slab 123 Llyn Gwynant 2 History of Moelwynion Climbing 20 27 Clogwyn yr Oen 123 1 Pentre 8 B4406 28 Carreg Keith 123 Yr Aran -bont Koselig Hour 28 Plas Gwynant Index of Climbs 000 29 Sleep Dancer Buttress 123 7 Penmachno A498 30 Clogwyn y Bustach 123 Cwm Lledr page 30 31 Craig Fach 123 A4085 Bwlch y Gorddinan (Crimea Pass) 1 Clogwyn yr Adar 32 32 Craig Newydd 123 Llyn Dinas MANOD & The TOWN QUARRIES MAP PAGE 123 Machno Ysbyty Ifan 2 Craig y Tonnau 36 33 Craig Stwlan 123 Beddgelert 44 34 Moelwyn Bach Summit Cliffs 123 Moel Penamnen 3 Craig Ddu 38 Y MOELWYNION MAP PAGE 123 35 Moelwyn Bach Summit Quarry 123 Carrog 4 Craig Ystumiau 44 24 29 Cnicht 47 36 Moelwyn Bach Summit Nose 123 Moel Hebog 5 Lone Buttress 48 43 46 B4407 25 30 41 Pen y Bedw Conwy 37 Moelwyn Bach Craig Ysgafn 123 42 Blaenau Ffestiniog 6 Daear Ddu 49 26 31 40 38 38 Craig Llyn Cwm Orthin -

Petrography of Roofing Slates

Earth-Science Reviews 138 (2014) 435–453 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Earth-Science Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/earscirev Petrography of roofing slates Victor Cárdenes a,⁎,ÁlvaroRubio-Ordóñezb,JörnWichertc, Jean Pierre Cnudde a, Veerle Cnudde a a Department of Geology and Soil Science, Ghent University, Krijgslaan 281, S8, 9000 Ghent, Belgium b Department of Geology, Area of Petrology and Geochemistry, Oviedo University, 33005 Oviedo, Spain c Faculty of Geoscience, Department for Geotechnics, Mining Academy, Freiburg Technical University, 09599 Freiberg, Germany article info abstract Article history: Roofing slate is one of the world's most popular dimension rock products. This special type of slate can be split Received 17 January 2014 into regular and thin tiles forming an exceptional covering material. Many historical heritage buildings along Accepted 17 July 2014 Europe use slate covers. Although slate has been quarried worldwide for centuries, in the second half of the Available online 28 July 2014 past century the production of roofing slate increased hugely, especially in Europe, where the largest outcrops known to date are located. Keywords: Despite its importance as a construction material, roofing slate has not been the target of a proportional number Roofing slate fi Dimension stone of scienti c publications, as compared to other materials such as granite, sandstone, marble or limestone. This Petrography could be due to the general perception that roofing slate is a rather simple rock with a relatively unvarying min- Geoscientific parameters eralogy consisting of quartz, chlorites and mica, and having a monotonous structure dominated by the slaty Quality control cleavage and various fracture planes. -

The Snowdonia National Park Partnership Plan

CYNLLUN THE SNOWDONIA NATIONAL PARK PARTNERSHIP PLAN THE STATUTORY MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR SNOWDONIA NATIONAL PARK > How to read this Plan 1. To find out about what the National Park Partnership Plan is and why it exists we recommend that you read Why we need a Plan and how it will be used (pages 14-21) 1. To find out about the most protected values of Snowdonia National Park we recommend that you read What makes Snowdonia Special (pg 24-83) 1. To find out about our vision for the National Park and how we want things to look in the future we recommend you read Where we want to get to (pages 84-89). 1. To find out in detail about our activities over the next five years we recommend that you read How we’ll get there (pages 90-155) 1. To find out the meaning of terms and other statutory requirements we recommend that you read the Glossary and The legal bit (pages 156-160) > CONTENTS 6 8 24 Foreword Introduction What makes š Foreword š Why we need a Plan Snowdonia Special? š A Partnership Plan š How the Plan will be used š Introduction to our Special Qualities š Local and National priorities š Our Special Qualities in detail š How this Plan was developed 84 90 154 Where do we The specifics What happens next? want to get to? š How we'll get there š How can you get involved š Action Plan, including Monitoring š Glossary of terms š Our long term vision for Snowdonia Indicators and Reporting Procedures š The Legal Bit >CONTENTs To check any words or terms you don’t understand turn to the Glossary section on page 156-157 >Foreword I am pleased to present to you the new statutory Management Plan for Snowdonia National Park Authority, as we approach our 70th anniversary celebrations in 2021. -

North Wales Winter Attractions

North Wales Winter Attractions www.gonorthwales.co.uk LLANGOLLEN 01 WREXHAM 02 RHYL 03 Llangollen Railway Techniquest GLYND Wˆ R SeaQuarium Travel through the picturesque Dee Valley from Llangollen. The 10 mile At Techniquest Glynd wˆr you can discover the amazing world of science See Seals and fabulous shows daily plus Sea Creatures within their natural standard gauge line passes some of the most stunning scenery in North Wales. with over 65 interactive exhibits and puzzles together with a programme habitats and witness the wonder of the ocean - an all weather attraction. of live science shows that all the family will enjoy. Friendly staff will be on Llangollen Railway offers services every day from Easter to September hand to help you get the most out of your visit and ensure you experience along with a host of special events including: an all-weather day out with a difference. You can bring your own food and refreshments to enjoy in our indoor café space or eat outside in our • A Day Out With Thomas • Santa Specials • Real Ale Trains attractive picnic area. The centre is open all year round including Bank • Fish and Chip Specials • Galas • Jazz Trains Holidays, (closed selected dates over Christmas - see website for details). Open Every day April - September Open 10.00 to 5.00pm Mondays to Fridays (School holidays) For winter opening dates call or visit our website. 10.00 to 4.30pm Tuesdays to Fridays (School term time) Open All year, except Christmas & Boxing Day Time 10am - 5pm 11.00 to 4.30pm Saturdays & Sundays Time 10am - 4pm The Station, Abbey Road, LLANGOLLEN LL20 8SN Mold Road, WREXHAM LL11 2AW East Parade, RHYL , Denbighshire LL18 3AF Phone 01978 860979 www.llangollen-railway.co.uk Phone 01978 293400 www.tqg.org.uk Phone 01745 344660 www.seaquarium.co.uk ©Matthew Collier COLWYN BAY 04 LLANDUDNO 05 TAL-Y-CAFN 06 The Welsh Mountain Zoo MOSTYN Bodnant Welsh Food Centre Go wild for a great day out - a friendly caring conservation zoo in lovely Gallery • Shop • Cafe Visit the award-winning Bodnant Welsh Food Centre and discover the garden surroundings. -

Migrant Culture Maintenance: the Welsh Experience in Poultney, Rutland County, 1900-1940

Migrant Culture Maintenance: The Welsh Experience in Poultney, Rutland County, 1900-1940 The Welsh comprised a highly visible ethno-linguistic community in Poultney, based on religion, language, culture, family ties, and participation in the area’s slate industry. BY Robert Llewellyn Tyler he old slate-quarrying town of Poultney is situated on the western border of Rutland County in Vermont. It was chartered by Benning Wentworth on September 21, 1761, and the town was organized on March 8, 1775.1 Poultney had few industries prior to 1800, and the town’s population grew slowly: numbering 1,121 in 1791; 1,950 in 1810; 1,909 in 1830; and 2,329 by 1850. In 1851, Daniel and S. E. Hooker opened the first slate quarry about three miles north of Poultney village and the industry grew rapidly, assisted by the arrival of the railroad in the same year. By 1860, Poultney could boast 16 slate companies employing some 450 workers and, in the words of contem- porary observers, by 1886 the prospects of the town were good: “Since 1875, it is said, the slate business of Poultney has more than doubled in volume, and has also greatly increased in profits. It is comparatively in its infancy yet, however, and if properly developed, will be a source of great wealth to the town.”2 The town drew migrants from across the Atlantic, initially from the countries of the United Kingdom and later from central, southern, and . Robert Llewellyn Tyler is a visiting professor at the University of Wales, New- port. He is the author of The Welsh in an Australian Gold Town (2011) and is pres- ently researching Welsh communities in the U.S. -

Blaenau Ffestiniog: Understanding Urban Character

Blaenau Ffestiniog: Understanding Urban Character Blaenau Ffestiniog: Understanding Urban Character 1 Acknowledgements As part of this study, historical research and mapping was carried out by Govannon Consultancy (Dr David Gwyn) under contract to Cadw. Dr Gwyn has acknowledged the assistance of the following individuals in the preparation of his study: John Alexander, Martin Duncan, Falcon Hildred, Peredur Hughes, Bill Jones, Gwynfor Pierce Jones, Mary Jones, Michael J.T. Lewis, Steffan ab Owain and Mike Schumann. The Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales (RCAHMW) provided most of the photography for this study. Sites for which further information is available on Coflein are listed in the appendix to this report. Finally, Cadw wishes to thank Falcon Hildred for the drawings on pages 16 and 24. 2 Contents Introduction 5 Aims of the Study 5 Historical Development 6 Blaenau Ffestiniog before the Slate Quarries 6 From Sheep to Slate: The Development of the Quarries 7 A Working Landscape 8 The Town Takes Shape: Infrastructure 10 Building a Town 14 Historical Topography 21 The Character of Building 23 Building Style and Detail 23 Materials: City of Slates? 32 Character Areas 37 1. Benar Road and The Square 37 2. Church Street 39 3. High Street and Summerhill 40 4. Diffwys Square and Lord Street 42 5. Maenofferen 43 6. Bethania and Mount Pleasant 44 7. Manod, Congl y Wal and Cae Clyd 46 8. Rhiwbryfdir 48 9. Tan y Grisiau, Glan y Pwll and Oakeley Square 49 Statement of Significance 51 Selected Sources 52 Appendix I 55 Endnotes 57 List of Maps pages 58–71 6. -

National Slate Museum Background Information Caption People Have Been Quarrying Slate in Wales for Over 1,800 Years

National Slate Museum Background information caption People have been quarrying slate in Wales for over 1,800 years. Welsh slate is considered to be the best in the world: it is easy to split yet very strong. These qualities mean it is particularly suitable for roofs. It was with the dawn of the Industrial Revolution in the late 18th century that the slate industry took off with Welsh slate being exported worldwide. What will I find there? The National Slate Museum is located in Gilfach Ddu, the buildings that once housed the workshops of the former Dinorwig Quarry. Built in 1870, these workshops catered for all the repair work at the quarry which, at its height, employed over 3,000 people. The Museum houses artefacts and exhibits. As well as having audio-visual aids and interpretation panels there are enthusiastic members of staff who are willing to answer your questions. What story do we tell? You can gain access to a wealth of knowledge about how the slate industry developed over the decades. Here are some of the main themes: Transport Quarry owners invested heavily in building roads and railways to improve the links between their quarries and the ports. In 1778, it was more expensive to get the slate from Dinorwig Quarry to the port of Felinheli than it was to take it all the way to Liverpool! Initially, the slate was carried in panniers on horseback, and then transported by boat to Cwm y Glo before being placed in wagons and taken to ships at the ports of Caernarfon or Felinheli. -

Oakeley Slate

OAKELEY SLATE The History of The Oakeley Slate Quarries Blaenau Ffestiniog PART THREE 1920 – 1968 From Peace to War and Back again Graham Isherwood - 2 - The History of The Oakeley Slate Quarries Blaenau Ffestiniog PART THREE 1920-1968 From Peace to War and Back again Continued from:- PART ONE 1800-1889 From Beginnings And PART TWO 1889 – 1920 From Amalgamation to the Great War to the Great Fall - 3 - 26 DEVELOPMENT AND DISASTER I, 1920 - 39 In the years following the First World war, the Oakeley Quarries faced many problems. Some were familiar - that big fall in 1912 having affected the western workings from floor 1 down to M within the area of walls 22 to 30. The Back Vein, mostly in the Upper and Middle Quarry was either cut off or worked out. The North Vein, apart from the isolated section on G floor, was not in work at all. The main workings were in the New Vein, these being developed both east and west from various points of access on all floors from G downwards. While most of the rather narrow New Vein in the Middle and Upper Quarries had been worked out, there were still isolated parts which were available. A summary of chambers at this time reveals that there were 47 chambers in work in the New Vein compared to 3 in work and 2 nearly ready in the Old Vein - a vast change in the state of things. The main areas available for development were: i) The New Vein in the Lower Quarry on the existing floors to east and west. -

Snowdonia Map and Tourist Guide

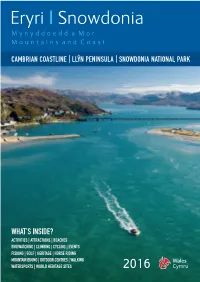

Making the Grade – a Guide to Quality Assurance 75 Visitor Attraction Quality Assurance Scheme Eryri | Snowdonia MAKING THE GRADE – to ensure that all areas important to your visit are of the best standard. TOURIST INFORMATION CENTRES Mynyddoedd a Môr A GUIDE TO QUALITY ASSURANCE Accommodating visitors with disabilities Mountains and Coast All the accommodation featured in this higher star ratings. Is it particularly important CANOLFANNAU CROESO publication has been independently assessed not to compare Guest Accommodation ratings All Visit Wales graded properties have an so you can make your choice in confidence, against Hotel ratings as different criteria are Access Statement. This statement tells visitors in a clear, accurate and honest way how the knowing that each place to stay has been used when assessing. Conwy given a rating according to the quality and property can meet their particular needs. ˆ The advice is always to check with an CAMBRIAN COASTLINE | LLY N PENINSULA | SNOWDONIA NATIONAL PARK facilities on offer. These ratings mean that Muriau Buildings, Rose Hill Street, establishment before booking to confirm that Three symbols have been introduced to help you can be sure of standards and choose Conwy LL32 8LD the accommodation offers the services and visitors with physical impairments find the the accommodation that’s just right for you. facilities that meet your needs – they will only Access Statements of most relevance to them. T. 01492 577566 Visit Wales/AA are the only checking agents be too pleased to help. Accommodation providers have selected Make the most of your stay by using [email protected] in Wales, checking out over 5000 places.