Intuition, Programming and Local Cinema Audiences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 Acp Bulletin

The Society of AUSTRALIAN CINEMA PIONEERS Please address all correspondence to SANDRA ALEXANDER National Honorary Secretary / Treasurer 27 Surfside Avenue Clovelly NSW 2031 (email – [email protected]) BULLETIN - OCTOBER 2017 NATIONAL EXECUTIVE MEETING MAY 2017 L-R - John Cronin, President SA, Bruce Leonard, retiring National Secretary- Treasurer, Robert Slaverio, National President 2016, Alan Stiles, President WA, Mike Selwyn, Sue Milliken, Murray Forrest, Alan Rydge, Mike Baard, Kerry Westwood, Secretary-Treasurer, Qld, Tom Jeffrey, Sharon Tapner, Treasurer, VIC, John Rochester, President NSW, Derek Screen, President VIC, Tim Read, National President 2017-2018, Sandra Alexander, Incoming National Secretary-Treasurer, Yurik Czyz, President Tas. embers of the National Executive Zareh Nalbandian of Animal Logic was elected Committee met at Sony Pictures National Cinema Pioneer of the Year. His Releasing, Market Street Sydney on distinguished career to date can be seen on the MMay 25 2017. Amongst the first items on the next page. Agenda was a formal resolution which was carried unanimously and with acclamation More details about the National Survey and the thanking our retiring National Secretary- resolutions passed at the NEC meeting can be Treasurer, Bruce Leonard for his 25 years of found on the Society’s new website. Please visit it devoted and highly successful service to the and consider writing an article or story for it. The Society. The very next resolution welcomed same applies to the Society’s Facebook page. It is and appointed Sandra Alexander as the new there to make communication between members National Secretary-Treasurer. quick and easy and I hope it encourages more get The NEC considered and approved nine togethers on an informal basis. -

2019 Acp Bulletin

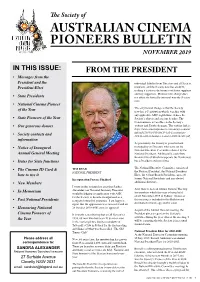

The Society of AUSTRALIAN CINEMA PIONEERS BULLETIN NOVEMBER 2019 IN THIS ISSUE: FROM THE PRESIDENT • Messages from the President and the individual liability from Directors and all Society President-Elect members, and the Society now has an ACN, making it easier to do business with our suppliers and key supporters. However the change does • State Presidents not affect the basically informal way the Society runs. • National Cinema Pioneer The only formal change is that the Society of the Year now has a Constitution which, together with any applicable ASIC regulations, defines the • State Pioneers of the Year Society’s objects and sets out its rules. The Constitution is accessible via the Society’s • Our generous donors website and Facebook pages. The website link is: https://www.cinemapioneers.com.au/wp-content/ uploads/2019/10/TSOACP-Ltd-Constitution- • Society contacts and FINAL-with-Schedules-1-and-2-300818-MU.pdf information As previously, the Society is governed and • Notice of Inaugural managed by its Directors who serve on the National Executive Committee chaired by the Annual General Meeting National President. Additionally, each State Branch (two of which incorporate the Territories) • Dates for State functions has a President and committee. • The Cinema ID Card & TIM READ The National Executive Committee consists of NATIONAL PRESIDENT the National President, the National President how to use it Elect, the 6 State Branch Presidents, up to 10 Incorporation Process Finalised former National Presidents and any elected • New Members additional directors. I wrote in this column last year that Sandra And, there is now an Annual General Meeting • In Memoriam Alexander, our National Secretary Treasurer would be lodging an application with ASIC for members which this year is being held for the Society to become incorporated as a on 28 November 2019 in Sydney. -

Annual Report 2017-2018 Patron His Excellency the Honourable Hieu Van Le AC, Governor of South Australia

Annual Report 2017-2018 Patron His Excellency the Honourable Hieu Van Le AC, Governor of South Australia Board Colette Smith Dr Tiffany Gill Dr Scott Graf President Vice President Medical Director (From September 2017) Scott Martin Alison Adair David Waterford Treasurer Secretary Director Anne Young Michele Herriot Danielle Dunlevey Director Director Director (From February 2018) Julie Black Chief Executive Officer Previous Directors Tracey Powell (Until January 2018) Dr Simon Burnet (Until August 2017) CONTENTS President’s Report 02 CEO’s Report 04 Health Services 05 Contact Centre 07 Kidsflix 08 Marketing and Fundraising 09 Research 10 Trust Monies and Beneficiaries 2017-2018 11 Treasurer’s Report 12 Financial 13 Acknowledgements, Sponsors & Thank you 16 Who we are Arthritis SA is a ‘for purpose’ organisation, established in 1975 to provide ways of supporting people with arthritis in the areas of medical assistance, education and research to find a cure or better treatment for the disease. Our Vision To improve the quality of life of people with arthritis and related conditions. Our Mission To be recognised as the leading provider in SA, that empowers people with arthritis and related conditions, to achieve the best possible quality of life through advocacy, education, self-management and the support of research. President’s Report Arthritis and other Arthritis SA’s significant commitment to musculoskeletal research has been maintained with continued conditions are support of both national and state research Australia’s fourth most programs. Additionally, funds were allocated to expensive group of retain continuity of the paediatric diseases and by 2032, it rheumatology nurse at Adelaide Women’s and is projected that the Children’s Hospital to ensure this critical service number of cases of remains available to support the youngest arthritis and other afflicted by the condition. -

I051 Companion Card Affiliate List 07 2021

South Australia South Australia Companion Card Affiliates List Updated July 2021 Page 1 of 42 APC I051 | July 2021 South Australia Table of Contents (Affiliates listed alphabetically) A J S B K T C L U D M V E N W F O Y G P Z H Q National Affiliates I R Page 2 of 42 APC I051 | July 2021 South Australia We would like to acknowledge the generous support of the following venues and events that have agreed to accept the Companion Card. A A Day on the Green (National) ABC Collinswood Centre, Adelaide Aberfoyle Community Centre Adelaide 4WD and Adventure Show Adelaide Antique Fair Adelaide Aquatic Centre Adelaide Arena Adelaide Auto Expo and Hot Rod Show Adelaide Beer and Barbecue Festival Adelaide Boat Show Adelaide Chamber Singers Adelaide City Council (ACC) • Adelaide City Council (ACC) Adelaide Aquatic Centre • Adelaide City Council (ACC) Adelaide Golf Links • Adelaide City Council (ACC) Adelaide Town Hall Page 3 of 42 APC I051 | July 2021 South Australia Adelaide Convention Centre Adelaide Craft and Quilt Fair Adelaide Entertainment Centre Adelaide Fashion Festival Adelaide Festival Adelaide Festival Centre • Adelaide Festival Centre Dunstan Playhouse • Adelaide Festival Centre Festival Theatre • Adelaide Festival Centre Her Majesty’s Theatre • Adelaide Festival Centre Space Theatre Adelaide Festival of Ideas Adelaide Film Festival Adelaide Football Club Adelaide Fringe Inc. Adelaide Gaol Adelaide Gardening and Outdoor Living Show Adelaide Guitar Festival Adelaide International Bird Sanctuary Adelaide International Raceway Page 4 of 42 -

Motion Picture Production: a Micro-Budget Model

Motion picture production: A micro-budget model By Richard Owen An exegesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy School of Business Federation University University Drive, Mount Helen Victoria, Australia Submitted: December 2016 Principal Supervisor – Associate Professor Elisa Backer Associate Supervisor – Dr Jacqueline Tuck ABSTRACT The film industry plays an important cultural and economic role in Australia. However, the film industry in Australia has struggled for many years under a subsidy-driven government intervention process that creates a high degree of dependence on a subsidy-centric model. Motion picture production costs worldwide have risen dramatically over the last decade with Hollywood production budgets commonly exceeding $100 million. Australia as a nation has a proven capability to produce respectable motion pictures at varying production budgets, although this capacity has become entrenched with taxpayers’ money. Historically, subsidy-driven industries in Australia trend towards collapse due primarily to cyclical fiscal deficits and changing funding imperatives at the Commonwealth level. As a PhD by exegesis, the focus of this research was to create, as well as evaluate, a new model of film production that would not be dependent on subsidies. This study evaluated a number of factors that were relevant to establishing a viable micro-budget model. Micro-budget films have received little research attention, with the focus being on major films. This research examined an alternative model, through the creation of a feature-length micro-budget film, called Stakes, and assessed it across a range of criterion to determine whether Australia’s film industry could be strengthened and potentially become self-sufficient. -

Adelaide Film Festival 14–25 October Program

Adelaide Film Festival 14–25 October Program AFF 2020 2 AFF 2020 04 Partners Patrons 05 Welcomes Special events 06 AFF in the Burbs AFF Hub The cornerstone 07 Opening Night of the Festival Closing Night Films and awards Adelaide Film Festival Investment Fund 08 Adelaide Film Festival Showcasing Investment Fund (AFFIF) (AFFIF) distinguishes our State’s premier screen event, generates opportunity, and 12 Don Dunstan Award enables the boldest, most daring Australian 13 Competitions projects to be realised. Change Award —Investing in jobs & local IP bold new Audience Award —Creating world leading content Jury —110+ projects since 2003 14 Feature Fiction Competition —Over 100 international awards 16 Documentary —More than 200 national accolades screen works Competition —Taking South Australia to the world 18 Architecture Sounds of Rebellion 19 Change the Status Quo 20 Australian Indies 21 Film Concept Lab Hanlon Larsen Fellowship 22 Contemporary World Cinema 24 Short Films AFFIF FILMS FROM THE 2020 SLATE: TOP: I AM WOMAN. DIR. UNJOO MOON. CENTRE: 2067. DIR. SETH LARNEY. 26 Queer as Film 27 Curiouser & Curiouser Talks & Events 28 Bettison & James Award Tarnanthi Short Films AFF in the time Grants for diverse voices 29 Black and White + talk of COVID-19: Industry Talks with Sandy George AFF events and screenings are managed by detailed and dedicated COVID-19 Safe and Management Plans. AFF has AFTRS Talk - undertaken all necessary and appropriate measures to ensure Frames of Transformation the Festival is as safe as possible. 30 Restaurants AFF follows implemented measures to protect the health and wellbeing of all South Australians and prevent the spread 31 (Port) Adelaide of COVID-19 in the community including social distancing, Film Festival hand sanitiser stations and the use of relevant personal 32 AFFIF VR protective equipment. -

Copyright and the Digital Economy

Response to the Issues Paper: Copyright and the Digital Economy Joint-Submission November 2012 _____________________________________________________________ This submission is made by the following : Australian Federation Against Copyright Theft (AFACT), the Australian Home Entertainment Distributions Association (AHEDA), the Motion Picture Distributors Association of Australia (MPDAA), the National Association of Cinema Operators (NACO), the Australian Independent Distributors Association (AIDA), the Independent Cinemas Association of Australia (ICAA), and the Media Entertainment and Arts Alliance (MEAA) collectively referred to as the Australian Film/TV Bodies. These associations represent the following: Ace Cinemas Group Gympie Cinemas Regal Twin Amalgamated Holdings Group Hamilton Cinema Regency Media Anchor Bay Home Entertainment Hayden Orpheum Regent Cinema Arcadia Twin Cinema Hervey Bay Cinemas Rialto Arts Centre Gold Coast Hopscotch Entertainment Ritz Cinemas Arts Lounge Glen Innes Hoyts Corporation Roma Cinemas Astor Theatre Hoyts/Studiocanal Roseville Cinemas Australian Federation Against Huskisson Pictures Roxy Cinema Nowra Copyright Theft Australian Home Entertainment Icon Sale Cinema Distributors Association Australian Independent Imax Saraton Cinemas Distributors Association Ballina Fair Cinemas Independent Cinemas Association Satellite Cinema Kingaroy of Australia Bay City Cinemas Batemans Bay Katherine Cinemas First Street Scottys Cinemas Becker Films Lake Cinema Boolaroo Semaphore Odeon Star Pty Ltd Belgrave Twin Cinema -

Australian Cinema Pioneers Bulletin November 2020

The Society of AUSTRALIAN CINEMA PIONEERS BULLETIN NOVEMBER 2020 IN THIS ISSUE: FROM THE PRESIDENT • Message from the President We directed those affected to sources of help and support and, where necessary, advised them • State Presidents and how to contact the relevant Cinema Benevolent the National Executive Societies. Committee In a time of job losses and instability in all sectors this support has been greatly • National Cinema Pioneer appreciated and we have had excellent feedback of the Year from members expressing gratitude for the information and the assistance. We maintain a • State Pioneers of the Year vital sense of community. Building on the Pioneers website established by • Humanitarian Award Kevin Adams the National Executive Committee undertook to give the website a fresh look. • Taking Care of Business The new website has been completed and was launched in October. The positive feedback has • Society contacts and been outstanding. Some of the major features that have been updated are the landing page, the information history of the Pioneers and the list of members as of June 2020. We are also delighted to advise • Notice of Annual General that Kevin will continue as webmaster. Meeting of Members Here is the link so please take a look https:// www.cinemapioneers.com.au. Special thanks to • State functions RUSSELL ANDERSON those who joined me on the Steering Committee, NATIONAL PRESIDENT Catherine Lavelle and Sandra Alexander and to • The Cinema ID Card & website designer Sam Vallellanes who gave a how to use it On behalf of Cinema Pioneers I’d like to thank refreshed polish to the site.