November 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liberal Women: a Proud History

<insert section here> | 1 foreword The Liberal Party of Australia is the party of opportunity and choice for all Australians. From its inception in 1944, the Liberal Party has had a proud LIBERAL history of advancing opportunities for Australian women. It has done so from a strong philosophical tradition of respect for competence and WOMEN contribution, regardless of gender, religion or ethnicity. A PROUD HISTORY OF FIRSTS While other political parties have represented specific interests within the Australian community such as the trade union or environmental movements, the Liberal Party has always proudly demonstrated a broad and inclusive membership that has better understood the aspirations of contents all Australians and not least Australian women. The Liberal Party also has a long history of pre-selecting and Foreword by the Hon Kelly O’Dwyer MP ... 3 supporting women to serve in Parliament. Dame Enid Lyons, the first female member of the House of Representatives, a member of the Liberal Women: A Proud History ... 4 United Australia Party and then the Liberal Party, served Australia with exceptional competence during the Menzies years. She demonstrated The Early Liberal Movement ... 6 the passion, capability and drive that are characteristic of the strong The Liberal Party of Australia: Beginnings to 1996 ... 8 Liberal women who have helped shape our nation. Key Policy Achievements ... 10 As one of the many female Liberal parliamentarians, and one of the A Proud History of Firsts ... 11 thousands of female Liberal Party members across Australia, I am truly proud of our party’s history. I am proud to be a member of a party with a The Howard Years .. -

VOTES and PROCEEDINGS No

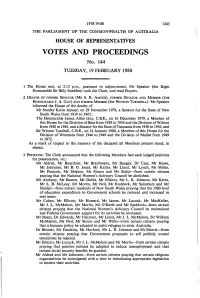

1978-79-80 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS No. 144 TUESDAY, 19 FEBRUARY 1980 1 The House met, at 2.15 p.m., pursuant to adjournment. Mr Speaker (the Right Honourable Sir Billy Snedden) took the Chair, and read Prayers. 2 DEATHS OF FORMER SENATOR (MR S. K. AMOUR), FORMER SENATOR AND MEMBER (THE HONOURABLE J. A. GUY) AND FORMER MEMBER (SIR WINTON TURNBULL): Mr Speaker informed the House of the deaths of: Mr Stanley Kerin Amour, on 29 November 1979, a Senator for the State of New South Wales from 1938 to 1965; The Honourable James Allan Guy, C.B.E., on 16 December 1979, a Member of this House for the Division of Bass from 1929 to 1934 and the Division of Wilmot from 1940 to 1946, and a Senator for the State of Tasmania from 1950 to 1956, and Sir Winton Turnbull, C.B.E., on 14 January 1980, a Member of this House for the Division of Wimmera from 1946 to 1949 and the Division of Mallee from 1949 to 1972. As a mark of respect to the memory of the deceased all Members present stood, in silence. 3 PETITIONs: The Clerk announced that the following Members had each lodged petitions for presentation, viz.: Mr Aldred, Mr Bourchier, Mr Braithwaite, Mr Bungey, Dr Cass, Mr Howe, Mr Johnston, Mr B. O. Jones, Mr Katter, Mr Lloyd, Mr Lynch, Mr Millar, Mr Peacock, Mr Shipton, Mr Simon and Mr Staley-from certain citizens praying that the National Women's Advisory Council be abolished. -

Women in the Federal Parliament

PAPERS ON PARLIAMENT Number 17 September 1992 Trust the Women Women in the Federal Parliament Published and Printed by the Department of the Senate Parliament House, Canberra ISSN 1031-976X Papers on Parliament is edited and managed by the Research Section, Senate Department. All inquiries should be made to: The Director of Research Procedure Office Senate Department Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Telephone: (06) 277 3061 The Department of the Senate acknowledges the assistance of the Department of the Parliamentary Reporting Staff. First published 1992 Reprinted 1993 Cover design: Conroy + Donovan, Canberra Note This issue of Papers on Parliament brings together a collection of papers given during the first half of 1992 as part of the Senate Department's Occasional Lecture series and in conjunction with an exhibition on the history of women in the federal Parliament, entitled, Trust the Women. Also included in this issue is the address given by Senator Patricia Giles at the opening of the Trust the Women exhibition which took place on 27 February 1992. The exhibition was held in the public area at Parliament House, Canberra and will remain in place until the end of June 1993. Senator Patricia Giles has represented the Australian Labor Party for Western Australia since 1980 having served on numerous Senate committees as well as having been an inaugural member of the World Women Parliamentarians for Peace and, at one time, its President. Dr Marian Sawer is Senior Lecturer in Political Science at the University of Canberra, and has written widely on women in Australian society, including, with Marian Simms, A Woman's Place: Women and Politics in Australia. -

Victorian Honour Roll of Women

INSPIRATIONAL WOMEN FROM ALL WALKS OF LIFE OF WALKS ALL FROM WOMEN INSPIRATIONAL VICTORIAN HONOUR ROLL OF WOMEN 2018 PAGE I VICTORIAN HONOUR To receive this publication in an accessible format phone 03 9096 1838 ROLL OF WOMEN using the National Relay Service 13 36 77 if required, or email Women’s Leadership [email protected] Authorised and published by the Victorian Government, 1 Treasury Place, Melbourne. © State of Victoria, Department of Health and Human Services March, 2018. Except where otherwise indicated, the images in this publication show models and illustrative settings only, and do not necessarily depict actual services, facilities or recipients of services. This publication may contain images of deceased Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Where the term ‘Aboriginal’ is used it refers to both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Indigenous/Koori/Koorie is retained when it is part of the title of a report, program or quotation. ISSN 2209-1122 (print) ISSN 2209-1130 (online) PAGE II PAGE Information about the Victorian Honour Roll of Women is available at the Women Victoria website https://www.vic.gov.au/women.html Printed by Waratah Group, Melbourne (1801032) VICTORIAN HONOUR ROLL OF WOMEN 2018 2018 WOMEN OF ROLL HONOUR VICTORIAN VICTORIAN HONOUR ROLL OF WOMEN 2018 PAGE 1 VICTORIAN HONOUR ROLL OF WOMEN 2018 PAGE 2 CONTENTS THE 4 THE MINISTER’S FOREWORD 6 THE GOVERNOR’S FOREWORD 9 2O18 VICTORIAN HONOUR ROLL OF WOMEN INDUCTEES 10 HER EXCELLENCY THE HONOURABLE LINDA DESSAU AC 11 DR MARIA DUDYCZ -

Senate Brief No. 3

No. 3 January 2021 Women in the Senate Women throughout Australia have had the right national Parliament (refer to the table on page 6). to vote in elections for the national Parliament for more than one hundred years. For all that time, There were limited opportunities to vote for women they have also had the right to sit in the before the end of the Second World War, as few Australian Parliament. women stood for election. Between 1903 and 1943 only 26 women in total nominated for election for Australia was the first country in the world to either house. give most women both the right to vote and the right to stand for Parliament when, in 1902, No woman was endorsed by a major party as a the federal Parliament passed legislation to candidate for the Senate before the beginning of the provide for a uniform franchise throughout the Second World War. Overwhelmingly dominated by Commonwealth. In spite of this early beginning, men, the established political parties saw men as it was 1943 before a woman was elected to the being more suited to advancing their political causes. Senate or the House of Representatives. As of It was thought that neither men nor women would September 2020, there are 46 women in the vote for female candidates. House of Representatives, and 39 of the 76 Many early feminists distrusted the established senators are women. parties, as formed by men and protective of men’s The Commonwealth Franchise Act 1902 stated interests. Those who presented themselves as that ‘all persons not under twenty-one years of age candidates did so as independents or on the tickets of whether male or female married or unmarried’ minor parties. -

Philip Mendes

I " 200106856 ECONOMIC RATIONALISM VERSUS SOCIAL JUSTICE: The Relationship Between the Federal Liberal Party and the Australian Council of Social Service 1983-2000 Philip Mendes Over the last decade and a half, the Australian Council of Social Service (ACOSS) _ the peak council of the non-government welfare sector - has become one of the most effective lobby groups in the country. During the period of Federal ALP Governments from 1983-1996, ACOSS exerted significant influence on government policy agendas in social security and a number of other areas, maintained a consistently high profile and status in media and public policy debates, and formed close links with other key interest groups such as the ACTU (Mendes, 1997:26). Whilst the election of the Howard Liberal Government in March 1996 introduced a tougher political and intellectual climate for ACOSS, the peak council appeared at least on the surface to retain its political influence. In particular from mid-1996 till the federal election of August 1998, ACOSS played a central role in Australia's tax reform debate. Yet approximately two years later, Australia has a new taxation system which is sharply at odds with ACOSS' key policy concems and recommendations. In addition, ACOSS has largely been frozen out of the tax debate by the Howard Govemment since the last federal election. Overall, ACOSS' policy agenda appears to have been increasingly marginalised by an unsympathetic govemment. This article explores the relationship between the Federal Liberal Party and ACOSS from 1983 to the current day. This period coincides with the Copyright of Full Text rests with the original copyright owner and, except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, copying this copyright material is prohibited without the permission of the owner or its exclusive licensee or agent or by way of a licence from Copyright Agency Limited. -

With the Benefit of Hindsight Valedictory Reflections from Departmental Secretaries, 2004–11

With the benefit of hindsight Valedictory reflections from departmental secretaries, 2004–11 With the benefit of hindsight Valedictory reflections from departmental secretaries, 2004–11 Edited by John Wanna • Sam Vincent • Andrew Podger Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: With the benefit of hindsight : valedictory reflections from departmental secretaries, 2004-11/ edited by John Wanna, Sam Vincent, Andrew Podger. ISBN: 9781921862731 (pbk.) 9781921862748 (ebook) Subjects: Civil service--Australia--Anecdotes. Australia--Officials and employees--Anecdotes. Other Authors/Contributors: Wanna, John. Vincent, Sam. Podger, A. S. (Andrew Stuart) Dewey Number: 351.94 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2012 ANU E Press Contents 2012 Valedictory Series Foreword . vii Introduction . ix Andrew Podger and John Wanna 1 . Yes, minister – the privileged position of secretaries . 1 Roger Beale 2 . My fortunate career and some parting remarks . 7 Andrew Podger 3 . Performance management and the performance pay paradox . 15 Allan Hawke 4 . Thirty-eight years toiling in the vineyard of public service . 29 Ric Smith 5. The last count – the importance of official statistics to the democratic process . 43 Dennis Trewin 6 . Balancing Life at Home and Away in the Australian Public Service . -

Representation of Women in Australian Parliaments 2014 9 July

RESEARCH PAPER SERIES, 2014–15 9 JULY 2014 Representation of women in Australian parliaments 2014 Dr Joy McCann and Janet Wilson Politics and Public Administration Executive summary • Across Australia women continue to be significantly under-represented in parliament and executive government, comprising less than one-third of all parliamentarians and one-fifth of all ministers. • Internationally, Australia’s ranking for women in national government continues to decline when compared with other countries. • The representation of women in Australia’s parliaments hovers around the ‘critical mass’ of 30 per cent regarded by the United Nations as the minimum level necessary for women to influence decision-making in parliament. • There is no consensus amongst researchers in the field as to why women continue to be under-represented in Australia’s system of parliamentary democracy, although a number of factors contribute to the gender imbalance. This paper includes discussion of some of the structural, social and cultural factors influencing women’s representation including the type of electoral system, the culture of political parties, and the nature of politics and the parliamentary environment in Australia. • This updated paper draws on recent data and research to discuss trends and issues relating to women in Australian parliaments within an international context. It includes data on women in leadership and ministry positions, on committees and as candidates in Commonwealth elections. Whilst the focus is on the Commonwealth Parliament, the paper includes comparative information about women in state and territory parliaments. • The issue of gender diversity is also discussed within the broader context of women in leadership and executive decision-making roles in Australia including local government, government boards and in the corporate sector. -

So Many Firsts: Liberal Women from Enid Lyons to the Turnbull

book REviEWS cork on the great Liberal tide.’ began to look more attractive to representation, their significant Protectionist and interventionist many of the Deakinites as their impact on government policies, Liberalism of the Victorian variety base crumbled. and their many hard won legislated occupied the policy space that The Protectionist push was freedoms in the second half of the Labor might otherwise have also weakening in New South twentieth century. filled, and worked closely and Wales. Michael Hogan shows that The Australian Liberal Party has comfortably with Labor. But as the Protectionists in New South held federal government for most the Victorian Socialist Party and Wales had largely collapsed as of Australia’s post-War history. Tom Mann gained influence, all an organised force by 1909, and Fitzherbert’s book reveals the story that changed. that the political battle there had of a few determined women and Nick Dyrenfurth shows Labor already slipped into the pattern of their dynamic personalities who as a party increasingly consumed Liberal (free trade) versus Labor. engaged in the cut-and-thrust of by the ideologies of class and Reid’s experience of his own state political pre-selection fights, jostled race, detailing its determination informed his claim that the future for ministerial portfolios, engaged to intensify the class division cleavage of Australian politics conservative Prime Ministers as between the parties (and oppose would be between Liberal and both allies and policy opponents, Watson’s moderation) and its Labor—between liberalism and and literally shaped the party itself. ‘populist scare campaign’ based socialism. There is so little academic research, on race to discredit the Liberals The Liberal Party resulting from let alone popular books, about in 1910 as soft on White the Fusion governed twice—with women and the Australian Liberal Australia. -

January 2021 Newsletter

We look forward to ‘seeing’ you by teleconference at the first Council meeting for the year on 4 February. Robyn Nolan, President of NCWA, has notified NCWV she was delighted to announce that Chiou See Anderson is the NCWA President-elect and she is very much Newsletter January 2021 looking forward to Chiou See joining the NCWA Executive in 2021. Quote: “At any time a woman must be capable of independence” Dame Margaret Georgina Guilfoyle Congratulations From President, Ronniet Milliken We were delighted to hear that our Young NCWV group in Year 12 have been highly successful in achieving their VCE. Lucy Skelton from Melbourne Girls’ College, Richmond, earned an ATAR of 95.10, including top 3% in several of her subjects. She also received an Environment Education Victoria Award after being nominated by her school. Congratulations to all Year 12 students who have successfully achieved their VCE after such a difficult year. We look forward to hearing about their plans for study, work or other options. 60th Annual Australia Day Pioneer Women’s Ceremony, Mon. January 18th 2021, 10:00–11:30 am Women’s Peace Garden, Epsom Road, Kensington, Welcome to the new year 2021 which promises to call on our between Westbourne Road and Coopers Lane, a reserves as we continue to advocate for the welfare of beautiful garden created by women in the women and girls in all aspects of their lives. International Year of Peace in 1986. This will At the initial meeting of the new Committee on 17 celebrate Victorian Pioneer Women, conducted by December, we reflected on Australia again being the ‘Lucky the National Council of Women of Victoria to Country’ when we consider ourselves compared to humanity acknowledge past and present women pioneers. -

Representation of Women in Australian Parliaments

Parliament of Australia Department of Parliamentary Services BACKGROUND NOTE 7 March 2012 Representation of women in Australian parliaments Dr Joy McCann and Janet Wilson Politics and Public Administration Section Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 1 How does Australia rate? ......................................................................................................................... 2 Parliamentarians ................................................................................................................................. 2 Parliamentary leaders and presiding officers ..................................................................................... 3 Ministers and parliamentary secretaries ............................................................................................ 4 Women chairing parliamentary committees ...................................................................................... 6 Women candidates in Commonwealth elections ............................................................................... 7 Historical overview................................................................................................................................. 10 First women in parliament ................................................................................................................ 10 Commonwealth .......................................................................................................................... -

A Dissident Liberal

A DISSIDENT LIBERAL THE POLITICAL WRITINGS OF PETER BAUME PETER BAUME Edited by John Wanna and Marija Taflaga A DISSIDENT LIBERAL THE POLITICAL WRITINGS OF PETER BAUME Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Creator: Baume, Peter, 1935– author. Title: A dissident liberal : the political writings of Peter Baume / Peter Baume ; edited by Marija Taflaga, John Wanna. ISBN: 9781925022544 (paperback) 9781925022551 (ebook) Subjects: Liberal Party of Australia. Politicians--Australia--Biography. Australia--Politics and government--1972–1975. Australia--Politics and government--1976–1990. Other Creators/Contributors: Taflaga, Marija, editor. Wanna, John, editor. Dewey Number: 324.294 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2015 ANU Press CONTENTS Foreword . vii Introduction: A Dissident Liberal—A Principled Political Career . xiii 1 . My Dilemma: From Medicine to the Senate . 1 2 . Autumn 1975 . 17 3 . Moving Towards Crisis: The Bleak Winter of 1975 . 25 4 . Budget 1975 . 37 5 . Prelude to Crisis . 43 6 . The Crisis Deepens: October 1975 . 49 7 . Early November 1975 . 63 8 . Remembrance Day . 71 9 . The Election Campaign . 79 10 . Looking Back at the Dismissal . 91 SPEECHES & OTHER PRESENTATIONS Part 1: Personal Philosophies Liberal Beliefs and Civil Liberties (1986) .