Interspirituality: Experiencing the Heart of the Six Sources the Rev

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Multifaith Continuing Education: Leading Faithfully in a Religiously Diverse World

Justus Baird: Multifaith Ed for “Lifelong Call to Learn” 9/17/08 1 Multifaith Continuing Education: Leading Faithfully in a Religiously Diverse World Justus N. Baird As a rabbi who directs a multifaith center in a Christian seminary, I often get asked about multifaith education. People ask me, “What curriculum should I use?” or “How can we teach our students about other religions?” Even more often I get asked, “Do you know a Muslim I can invite to speak at our program?” But rarely do I get asked, “Why should we be doing interfaith education at all?” A rabbinic colleague of mine put it to me this way: “I just can’t articulate why interfaith is important to focus on,” he said. What worries him most about serving his congregation is not how much his congregants know about other faiths. “Other than making sure we can all just get along, why does this matter?” he asked. Let’s be honest: most of us know precious little about our own religious traditions, so why should we spend our valuable time learning about other faiths? The aim of this chapter is to articulate what multifaith education is, why it should be part of any continuing education program, and address some of the challenges that confront multifaith education. Part one answers the ‘why do interfaith?’ question articulated by my colleague and makes the case for including multifaith learning in any continuing education program. Part two defines multifaith education and describes various approaches to multifaith education. Part three articulates the challenges and barriers to multifaith education. -

Interfaith Formation for Religious Leaders in a Multifaith Society: Between Meta-Spiritualities and Strong Religious Profiles

Interfaith Formation for Religious Leaders in a Multifaith Society: Between Meta-Spiritualities and Strong Religious Profiles Tabitha Walther Religious leaders today need new skills to meet the religiously pluralistic societies in which they serve. The aim of this essay is to explore this plur- alistic challenge and find approaches that would effectively educate relig- ious leaders for the multireligious context in which they will serve as religious professionals. Cultural and religious diversity is not new. What is new is that this plur- alism is experienced by every citizen and not just by cultural or religious mi- norities. Western societies have been pluralized. Migration and globalization have hastened this process of pluralization in ways previously unknown. Re- ligious leaders for today and tomorrow need to develop tools to serve effec- tively in a multireligious context. They will not just minister to their own people, but beyond their own faith traditions, in between them, and within multiple religious traditions. This is true for a religious community that is multi-religious at its boundaries, as well as for public institutions with multi- religious populations, such as prisons, hospitals, schools, and universities. Tabitha Walther, LTheol, lecturer and trained hospital chaplain, Faculty of Theology, The University of Basel, Missionstrasse 17a, 4055 Basel, Switzerland (E-mail: Tabitha.Walther @unibas.ch). Reflective Practice: Formation and Supervision in Ministry WALTHER 129 Religious pluralism knows many manifestations and is known in all religious traditions. People who are grounded in multiple religious trad- itions, in New Age thought, or people who combine teachings from various religious traditions, ask for spiritual support at critical life moments. -

What Do College Students Want? a Student-Centered Approach to Multifaith Involvement

Journal of Ecumenical Studies, 45:1, Winter 2010 WHAT DO COLLEGE STUDENTS WANT? A STUDENT-CENTERED APPROACH TO MULTIFAITH INVOLVEMENT Paul V. Sorrentino PRECIS The author presents research findings about the preferences of college students as they consider coming together with people of other faiths in multifaith settings. He discusses what works well and what does not. Select quotations from interviews are included. The author suggests a practical model for multifaith work on campus based on the principles represented in the acronym “RAM.” Multifaith involvement should include being Respectful toward the beliefs of others, being Authentic to one’s own tradition, and having Meaningful interreligious interaction. Introduction Our university and college campuses focus a great deal of attention on di- versity. This is a proper focus and one that is needed in our society. Religious diversity, however, is often left off the agenda and may be subsumed under a rising tide of secular animosity that says there is no place for religious expres- sion in the academy. The raison d'être of an academic institution is education. We must decide how religion and religious diversity fits into that goal. Should we safeguard the academic enterprise, viewed as largely secular, by making religious expression a private matter? Do we enhance learning by exposing students to various forms of religion? If so, what is the best way to do it? How do we respect differences __________________ Paul V. Sorrentino (Conservative Congregational Christian Conference) has been Director of Reli- gious Life at the Cadigan Center for Religious Life at Amherst (MA) College since 2000, as well as serving Intervarsity Christian Fellowship since 1981 as a regional coordinator, team leader (Amherst College, since 1991), area director (in Western New England, 1985–91), and campus staff (Colby College, University of Maine, and Eastern Maine Vo Tech Institute (1981–85). -

ATS Christian Hospitality and Pastoral Practices in a Multifaith Society

PRACTICING GOD’S SHALOM AND CHRIST’S PEACE IN PASTORAL MINISTRY Bethany Theological Seminary Russell Haitch Summary Seven faculty members met, along with three Jewish and Muslim scholars who joined us via Skype, for consultation on how to educate students for pastoral ministry in multifaith settings. We had thirteen hours of face to face meetings and multiple email discussions. Two educational foci were the practice of prayer in hospital settings and the practice of receiving and extending hospitality during academic courses that take place in cross-cultural settings. Our theological focus was practicing “God’s shalom and Christ’s peace,” concepts that figure prominently in Bethany’s Anabaptist heritage and current mission statement. One distinctive feature of this consultation was the amount of time spent reading about, arguing over, and experimenting with “scriptural reasoning” (or SR), a term that refers to the activity of the Scriptural Reasoning Society, started in 1994. The practice of SR brings together Jewish, Christian, and Muslim participants for the purpose of reading sacred texts; participants “offer each other hospitality” to read one another’s sacred texts as they would their own.1 As a result of this ATS-funded project, six of the seven faculty participants decided to alter their teaching by revising course syllabi and by integrating new insights into Bethany’s ongoing curricular review. Introduction Bethany is the one seminary for the Church of the Brethren, an Anabaptist and Pietist denomination started in Germany in 1708. Though fairly small, largely rural and somewhat tribal, the Brethren have a history of serving in international and multifaith settings. -

World Interfaith Harmony Week Multifaith Clergy / Faith Leader

World Interfaith Harmony Week MultiFaith Clergy / Faith Leader Breakfast, Toledo, OH Sponsored by the MultiFaith Council of NW Ohio, in conjunction with Compassion Games International and MLK 40 Days of Service Fifty-five guests attended the MultiFaith Clergy / Faith Leader Breakfast, in observance of World Interfaith Harmony Week that was held Wednesday, February 5, 2020, 8:30 – 10:30 am, at Christ Presbyterian Church, 4225 W Sylvania Ave, Toledo, OH 43623. Twenty-six volunteers catered a deluxe continental breakfast, with pastries, fruit, yogurt, granola, juice and water. A local coffee shop, Black Kite Coffee and Pies donated coffee and tea. The guests were from diverse faith traditions, including Baha’i, Buddhism (2 sanghas), Protestant Christianity (at least 5 denominations), Roman Catholic, Judaism, Islam (2 mosques), New Thought, Pagan, Sufi Universalism, Unitarian Universalism. The program started with the Love One Another challenge. Video Clergy, faith and community leaders had a good opportunity to mingle and chat with others, learn about MultiFaith Council activities, and to discuss collaborative solutions to their choice of three critical issues – what faith groups can do to alleviate 1. loneliness / isolation - This article by Nicolas Kristof is a very good commentary on the seriousness of the issue of loneliness; 2. climate change - https://citizensclimatelobby.org/; and 3. violence against faith communities - In 2018, 36 hate groups were tracked in Ohio. Table discussion was lively. The report outs were recorded here for future use by the Council. The event concluded with a sending forth by the Rev. Otis Gordon of Warren ANE Church and an optional tour of Christ Presyterian Church, led by the Associate Minister Rev. -

Multiple Religious Belonging Open Access

Open Theology 2017; 3: 38–47 Multiple Religious Belonging Open Access Daan F. Oostveen* Multiple Religious Belonging: Hermeneutical Challenges for Theology of Religions DOI 10.1515/opth-2017-0004 Received May 1, 2016; accepted September 23, 2016 Abstract: The phenomenon of multiple religious belonging is studied from different perspectives, each of which reveals a different understanding of religion, religious diversity and religious belonging. This shows that the phenomenon of multiple religious belonging is challenging the applicability of these central notions in academic enquiry about religion. In this article, I present the different perspectives on multiple religious belonging in theology of religions and show how the understanding of some central scholarly notions is different. In Christian theology, the debate on multiple religious belonging is conducted between particularists, who focus on the uniqueness of religious traditions, and pluralists, who focus on the shared religious core of religious traditions. Both positions are criticized by feminist and post-colonial theologians. They believe that both particularists and pluralists focus too strongly on religious traditions and the boundaries between them. I argue that the hermeneutic study of multiple religious belonging could benefit from a more open understanding of religious traditions and religious boundaries, as proposed by these feminist and post-colonial scholars. In order to achieve this goal we could also benefit from a more intercultural approach to multiple religious belonging in order to understand religious belonging in a non- exclusive way. Keywords: multiple religious belonging, theology of religions, religious diversity, religious traditions, religious boundaries, hybrid religiosity In the contemporary globalized world, cultural and religious diversity leads to increasingly complex identities and social groups. -

MAGAZINE and ANNUAL REPORT Stories

Volume LIV Fall 2015 Six new THE STORY seminarians share their MAGAZINE AND ANNUAL REPORT stories Bishop in Residence Judith Craig reflects on a pastoral life Events: Alumni Day, Williams Institute Lectures and Schooler Institute Sandy Lutz, influential lay leader, chairs MTSO’s board Meet new faculty members in New Testament, homiletics and Hebrew Bible www.mtso.edu Methodist Theological School in Ohio Methodist Theological School in Ohio Contents FROM THE PRESIDENT FACULTY Why MTSO doesn’t deliver education . 1 Bridgeman brings a commitment to teaching and activism . 13 ON CAMPUS Schellenberg shares his curiosity about A preview of campus events . 2 early Christians. .14 Meet Admissions Director Benjamin Hall. 3 Beyond the classroom: faculty activities . 16 Fall Admissions Open House . 3 Emeriti obituaries . 17 Sandy Lutz ascends to chair of MTSO’s board . 4 IN REVIEW We’re now powered, in part, by the sun . 5 Images of a good year. .22 Bishop Judith Craig’s pastoral life . 6 REPORT TO DONORS STUDENTS Financial information . 23 Six new arrivals introduce themselves . 8 Donor Honor Roll . 24 ALUMNI The Sterling Society: recognizing planned giving . 26 A wise perspective on Christianity and war . 10 MTSO Board of Trustees roster . 27 Alum news . .11 Restricted student scholarship giving. .28 A window on our heritage h Fifteen years ago, MTSO embarked on a new millennium by dedicating Gault Hall, a gift of the Stanley C. and Flo K. Gault family and many other donors. The hall’s Sterling Roof Terrace is graced by “Portal of God’s Love,” the stained-glass roundel illuminated by the morning light on the cover of this issue of The Story. -

Multi-Faith Resources for the Children's Sabbath

Resources for a Multifaith Children’s Sabbath Celebration multifaith Children’s Sabbath offers a powerful and meaningful opportunity to bring A together people from all across your community who may never have connected before. It is a chance to highlight our shared concern—across religious traditions—for justice and protecting and nurturing children. It is a meaningful time to discover what our different faith traditions hold in common as well as to learn about the unique perspectives, texts and traditions that each brings. It is a time to unite in shared commitment to take action to solve the problems facing children in our communities and nation. This Multifaith Children’s Sabbath Section is designed to be “evergreen” and not updated annually; There is an annual Children’s Sabbath supplement that provides new material tied to the year’s Children’s Sabbath theme that you should print out each year for fresh resources Children’s Defense Fund l 1 RESOURCES FOR A MULTIFAITH CHILDREN’S SABBATH CELEBRATION Planning a Multifaith Children’s Sabbath Celebration: Be sure to read the planning steps for organizing a multifaith community-wide service which are outlined in the “Planning Your Children’s Sabbath” section of the Children’s Sabbath manual. Follow the planning steps to bring together a planning committee that represents the many religious traditions in your community. Multifaith Children’s Sabbath Service: Following, you will find materials to help to create your own multifaith Children’s Sabbath service that is inclusive, respectful of different traditions, focused on the Children’s Sabbath core themes, and adaptable to your particular community and leadership: l A suggested outline for your multifaith community-wide Children’s Sabbath service; l A variety of prayers, readings, and litanies that may be used in a multifaith Children’s Sabbath service. -

Teacher Resource Pack for Teachers Working with Students in Year 10+ Martyr from 15 Sep - 10 Oct 2015 for Students in Year 10 and Up

MARTYR TEACHER RESOURCE PACK FOR TEACHERS WORKING WITH STUDENTS IN YEAR 10+ MARTYR FROM 15 SEP - 10 OCT 2015 FOR STUDENTS IN YEAR 10 AND UP HOW FAR WILL YOU GO FOR WHAT YOU BELIEVE? Benjamin won’t do swimming at school. His mum thinks he’s on drugs or has body issues. But Benjamin has found God and mixed-sex swimming lessons offend him. Fundamentalism and tolerance clash in this funny, provocative play by leading German playwright, Marius von Mayenburg. Martyr considers how far we should go in accommodating another’s faith, and when we should take a stand for our own opposing beliefs. This topical production follows Actors Touring Company’s highly acclaimed The Events, seen at the Young Vic last year. This show contains some strong language and nudity. Page 2 MARTYR - TEACHER RESOURCES CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 CONTEXT 6 • A BRIEF SUMMARY OF THE PLAY 7 • INTERVIEW WITH RAMIN GRAY - DIRECTOR 8 • INTERVIEW WITH MARIUS VAN MAYENBURG - WRITER 12 • ABOUT ACTORS TOURING THEATRE & THE UNICORN 15 PRACTICAL ACTIVITIES • INTRODUCTION & DEFINITIONS OF KEY WORDS 16 • SEQUENCE ONE - BELIEF AND TOLERANCE 17 • SEQUENCE TWO - EXPLORING MARTYRDOM 20 RESOURCE 1: INFO ABOUT MARTYRS 24 RESOURCE 2: ROLE ON THE WALL OUTLINE 27 • SEQUENCE THREE - INTERPRETATION 28 RESOURCE 3: EXCLUSIVE, INCLUSIVE & PLURALIST CHRISTIANS 31 RESOURCE 4: INTERPRETING THE BIBLE 32 • POST-SHOW SEQUENCE - BENJAMIN & MISS WHITE 33 RESOURCE 5: PLAN OF THE WESTON THEATRE 37 RESOURCE 6: MISS WHITE’S SPEECH 38 Page 3 MARTYR - TEACHER RESOURCES INTRODUCTION Martyr (noun) 1: a person who voluntarily suffers death as the penalty of witnessing to and refusing to renounce a religion. -

Theological Education

Theological Education Volume 47, Number 2 ISSUE FOCUS 2013 Christian Hospitality and Pastoral Practices in a Multifaith Society—Reports and Reflections Taking Interfaith Off the Hill: Revelation in the Abrahamic Traditions Gregory Mobley The Pastoral Practice of Christian Hospitality as Presence in Muslim-Christian Engagement: Contextualizing the Classroom Mary Hess Raising Awareness of Christian Hospitality and Pastoral Practices: Equipping Ourselves for a Multifaith World Barbara Sutton Christian Hospitality in a World of Many Faiths: Equipping the New Generation of Religious Leaders in a Multifaith Context Eleazar S. Fernandez Caring Hospitably in Multifaith Situations Daniel S. Schipani Interfaith Perspectives on Religious Practices Timothy H. Robinson and Nancy Ramsay Putting into Practice an Intercultural Approach to Spiritual Care with Veterans Carrie Doehring and Kelly Arora Table Fellowship with Our Buddhist Neighbors for Beloved Community Paul Louis Metzger Developing a Cultural Competency Module to Facilitate Christian Hospitality and Promote Pastoral Practices in a Multifaith Society Paul De Neui and Deborah Penny OPEN FORUM Pedagogic Principles for Multifaith Education Rabbi Or N. Rose Christian Hospitality and Muslims Amir Hussain Full text may be accessed Muslim Studies in a Christian Theological School: only on the University of The Muslim Studies Program at Emmanuel College in Toronto Toronto Press website. Mark G. Toulouse ISSN 0040-5620 Theological Education is published semiannually by The Association of Theological Schools IN THE UNITED STATES AND CANADA 10 Summit Park Drive Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15275-1110 Daniel O. Aleshire, Executive Director STEPHEN R. GRAHAM Senior Editor ELIZA SMITH BROWN Editor LINDA D. TROSTLE Managing Editor For subscription information or to order additional copies or selected back issues, please contact the Association. -

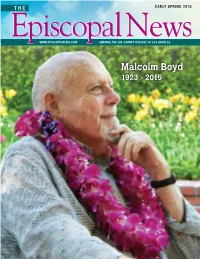

Malcolm Boyd

THE EARLY SPRING 2015 EpiscopalEpiscopal NewsNews WWW.EPISCOPALNEWS.COM SERVING THE SIX-COUNTY DIOCESE OF LOS ANGELES Malcolm Boyd 1923 - 2015 FROM THE BISHOP Lenten journeys to new life n commemorating a person who has died, the of civil rights and Book of Common Prayer guides us to petition racial equity in the JOHNNY BUZZERIO JOHNNY I“…through Jesus Christ our Lord; who rose 1960s and ’70s, and J. Jon Bruno victorious from the dead, and comforts us with the next as an openly Bishop of Los Angeles blessed hope of everlasting life. For to your faithful gay man and priest people, O Lord, life is changed, not ended; and when having travelled ear- our mortal body lies in death, there is prepared for lier, in the 1950s, By J. Jon Bruno us a dwelling place eternal in the heavens.” out of his career in This prayer’s insight that “life is changed, not Hollywood’s heyday ended” is on my heart as I think of our beloved into the beginnings friend and priest Malcolm Boyd, who has influenced of his theological education and path to priesthood. and strengthened my own faith throughout the past Finally, his serious illness with pneumonia in the last 50 years. From 1965 when I read his bestseller Are four weeks of his life was another passage that he You Running with Me, Jesus? — the same year of made with grace and courage. the marches from Selma to Montgomery — I have These were by no means easy paths, and they been deeply moved by his courage and guidance. -

Union Network FA15 VWEB2 2

NETWORKThe Magazine of Union Theological Seminary | Fall 2015 NETWORK Vol. 1, No. 1 | Fall 2015 On the Cover Benjamin Perry ’15 (left) and Shawn Torres (right) at Published by a December 18, 2014 street demonstration (die-in) at Union Theological Seminary in the City of New York Broadway and Reinhold Niebuhr Place (120th Street), New York. 3041 Broadway at 121st Street New York, NY 10027 A week after a New York City grand jury announced [email protected] that no charges would be filed against police officers 212-280-1590 involved in the death of Eric Garner on Staten Island, Union hosted a multifaith prayer breakfast on December 18 convened jointly by Union, Auburn Editors-in-Chief Graphic Design Seminary, The Riverside Church, Interfaith Center Marvin Ellison and Kevin McGee Ron Hester Design of NY, Milstein Center For Interreligious Dialogue, and the Drum Major Institute. At breakfast, speak- Editor Principal Photographers ers included Martin Luther King III and Rev. Traci Jason Wyman Ron Hester Blackmon along with organizers from Ferguson, Richard Madonna MO: Jelani Brown, Tara Thompson, and Johnetta Class Notes/In Memoriam Kevin McGee Elzie (who was named by Fortune magazine in March Leah Rousmaniere Rebecca Stevens 2015 to its World’s 50 Greatest Leaders list). Union Tom Zuback students Benjamin Perry ’15 and Shawn Torres also Writers Union Theological Seminary spoke about their starkly different experiences after Emily Brewer ’15 Photo Archive being arrested in November while participating Elizabeth Call in the same NYC street demonstration. The prayer Jamall Calloway Visit us online: breakfast concluded with participants holding a Todd Clayton ’14 utsnyc.edu die-in as pictured on the cover.