Percutaneous Balloon Kyphoplasty and Mechanical Vertebral

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Post–Vertebral Augmentation Back Pain: ORIGINAL RESEARCH Evaluation and Management

Post–Vertebral Augmentation Back Pain: ORIGINAL RESEARCH Evaluation and Management S. Kamalian BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE: Vertebral augmentation is an established treatment for painful osteo- R. Bordia porotic vertebral fractures of the spine. Nevertheless, patients may continue to have significant back pain afterward. The purpose of this study was to assess the source of persistent or recurrent back pain A.O. Ortiz following vertebral augmentation. MATERIALS AND METHODS: Our institutional review board approved this study. We evaluated 124 consecutive patients who underwent vertebral augmentation for painful osteoporotic vertebral frac- tures. All patients were evaluated after 3 weeks, 3 months, and 1 year following their procedure. Patients with any type of back pain after their procedure were examined under fluoroscopy. RESULTS: Thirty-four of 124 (27%) patients were men, and 90/124 (73%) were women. Persistent or recurrent back pain, not due to a new fracture or a failed procedure, was present in 29/124 (23%) patients. The source of pain was most often attributed to the sacroiliac and/or lumbar facet joints (25/29 or 86%). Seventeen of 29 (59%) patients experienced immediate relief after facet joint injection of a mixture of steroid and local anesthetic agents. The remaining 12 (41%) had relief after additional injections. Ten (34%) patients ultimately required radio-frequency neurolysis for long-term relief. CONCLUSIONS: Back pain after vertebral augmentation may not be due to a failed procedure but rather to an old or a new pain generator, such as an irritated sacroiliac or lumbar facet joint. This is of importance not only for further pain management of these patients but also for designing trials to compare the efficacy of vertebral augmentation to other treatments. -

Procedure Codes

NEW YORK STATE MEDICAID PROGRAM ORDERED AMBULATORY PROCEDURE CODES Ordered Ambulatory Procedure Codes Table of Contents GENERAL INFORMATION ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------2 LABORATORY SERVICES INFORMATION-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------2 RADIOLOGY INFORMATION------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------3 MMIS MODIFIERS --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------6 RADIOLOGY SERVICES------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------7 DIAGNOSTIC RADIOLOGY (DIAGNOSTIC IMAGING) ------------------------------------------------------------------------7 DIAGNOSTIC ULTRASOUND SERVICES- -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 20 RADIOLOGIC GUIDANCE....................................................................................................................................25 BREAST, MAMMOGRAPHY --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 26 BONE/JOINT STUDIES --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 26 RADIATION ONCOLOGY SERVICES --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 27 NUCLEAR -

Vertebral Augmentation ICD 9 Codes: Osteoporosis 733. 0, Vertebra

BRIGHAM AND WOMEN’S HOSPITAL Department of Rehabilitation Services Physical Therapy Standard of Care: Vertebral Augmentation ICD 9 Codes: Osteoporosis 733. 0, Vertebral Fracture closed 805.8, Pathological fracture of Vertebrae 733.13 Vertebral augmentation, known as vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty, is a minimally invasive procedure that is used to treat vertebral fractures. Vertebral fractures are the most common skeletal injury associated with osteoporosis, and it is estimated that more than 750,000 occur annually in the United States.1 Up to one quarter of people over 50 years of age will have at least one vertebral fracture in their life time secondary to osteoporosis.2 According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the operational definition of osteoporosis is a bone density measure >2.5 standard deviations (SD) below the mean of young healthy adults of similar race and gender.3 Primary osteoporosis is related to the changes in postmenopausal women secondary to reduction of estrogen levels and related to age-related loss of bone mass. Secondary osteoporosis is the loss of bone caused by an agent or disease process. 1,4 (See Osteoporosis SOC) The severity of vertebral fractures can be assessed by the Genat semiquantitative method. Commonly used by radiologists, this scale assesses the severity of the fracture visually and has been shown to be reliable.5 Genat Semiquantitive Grading System for Vertebral Deformity5 Grade 0- normal vertebral height Grade 1- minimal fracture- 20-25% height decrease Grade 2- moderate fracture- 25-40% height decrease Grade 3-severe- >40% height decrease Standard methods of diagnosing vertebral fractures are imaging, including the following: CT scan, MRI, and radiography. -

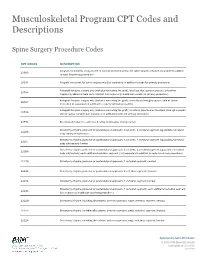

Musculoskeletal Program CPT Codes and Descriptions

Musculoskeletal Program CPT Codes and Descriptions Spine Surgery Procedure Codes CPT CODES DESCRIPTION Allograft, morselized, or placement of osteopromotive material, for spine surgery only (List separately in addition 20930 to code for primary procedure) 20931 Allograft, structural, for spine surgery only (List separately in addition to code for primary procedure) Autograft for spine surgery only (includes harvesting the graft); local (eg, ribs, spinous process, or laminar 20936 fragments) obtained from same incision (List separately in addition to code for primary procedure) Autograft for spine surgery only (includes harvesting the graft); morselized (through separate skin or fascial 20937 incision) (List separately in addition to code for primary procedure) Autograft for spine surgery only (includes harvesting the graft); structural, bicortical or tricortical (through separate 20938 skin or fascial incision) (List separately in addition to code for primary procedure) 20974 Electrical stimulation to aid bone healing; noninvasive (nonoperative) Osteotomy of spine, posterior or posterolateral approach, 3 columns, 1 vertebral segment (eg, pedicle/vertebral 22206 body subtraction); thoracic Osteotomy of spine, posterior or posterolateral approach, 3 columns, 1 vertebral segment (eg, pedicle/vertebral 22207 body subtraction); lumbar Osteotomy of spine, posterior or posterolateral approach, 3 columns, 1 vertebral segment (eg, pedicle/vertebral 22208 body subtraction); each additional vertebral segment (List separately in addition to code for -

Effectiveness of Cementoplasty for Vertebral Augmentation in Multiple Myeloma: a Case Series

WCRJ 2017; 4 (2): e882 EFFECTIVENESS OF CEMENTOPLASTY FOR VERTEBRAL AUGMENTATION IN MULTIPLE MYELOMA: A CASE SERIES G. TESTA1, M. PRIVITERA1, T. FIDILIO1, G. DI STEFANO1, A. VESCIO1, G. D’ANGELO2, V. PAVONE1 1Department of Orthopedics and Traumatologic Surgery, AOU Policlinico-Vittorio Emanuele, University of Catania, Catania, Italy 2Department of Human Pathology in Adult and Developmental Age “Gaetano Barresi” – Unit of Paediatrics, University of Messina, Messina, Italy Abstract – Objective: Multiple myeloma (MM) is a neoplasm characterized by the proliferation of somatically mutated plasma cells that tend to expand within the bone marrow and affect mul- tiple locations throughout the bone marrow. When it is located in vertebral areas it causes bone lesions with pain, kyphosis, walking impairments, and disability. Different types of treatments are available. The goal of this study is to report our experience regarding the treatment of vertebral fractures from multiple myeloma using cementoplasty. Patients and Methods: From January 2012 to December 2015, 38 patients with multiple mye- loma and multilevel vertebral fractures were treated. Seventeen patients underwent conservative treatment (group 1), and 21 patients underwent vertebral augmentation with percutaneous ce- mentoplasty (group 2). Both groups were clinically evaluated at 1, 6 and 12 months using a visual analogic scale (VAS) for pain, SF-36 and ODI Score Questionnaires. Radiographic evaluation was performed to verify the quality of cementoplasty and complications. Results: Mean follow-up was 23.7 months. Mean VAS score in group 1 decreased from 7.1 pre-operatively to 3.9 at final follow-up (p<0.05). In group 2, this score decreased from 7.3 pre-op- eratively to 2.3 at final follow-up (p<0.05). -

Vertebroplasty and Percutaneous Vertebral Augmentation

Medicare Part C Medical Coverage Policy Vertebroplasty and Percutaneous Vertebral Augmentation Origination Date: December 16, 2002 Vertebroplasty August 20, 2003 Kyphoplasty Review Date: June 17, 2020 Next Review: June, 2022 ***This policy applies to all Blue Medicare HMO, Blue Medicare PPO, Blue Medicare Rx members, and members of any third-party Medicare plans supported by Blue Cross NC through administrative or operational services. *** DESCRIPTION OF PROCEDURE OR SERVICE Vertebroplasty Percutaneous vertebroplasty is a therapeutic, interventional radiologic procedure, which consists of the injection of a biomaterial (usually polymethylmethacrylate- bone cement) under imaging guidance (either fluoroscopy or CT) into a cervical, thoracic or lumbar vertebral body lesion for the relief of pain and the strengthening of bone. Percutaneous Vertebral Augmentation This is also known as balloon-assisted Percutaneous Vertebroplasty or Kyphoplasty. The procedure is similar to percutaneous vertebroplasty in that stabilization of the collapsed vertebra is accomplished by the injection of the same biomaterial into the body of the vertebra. The primary difference is that the fracture is partially reduced with the insertion of an inflatable balloon tamp. Once inflated, the balloon tamp (plug) restores some height to the vertebral body, while creating a cavity that is filled with bone cement. POLICY STATEMENT Coverage will be provided for vertebroplasty or percutaneous vertebral augmentation when it is determined to be medically necessary because the -

A Novel and Convenient Method to Evaluate Bone Cement Distribution Following Percutaneous Vertebral Augmentation

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN A novel and convenient method to evaluate bone cement distribution following percutaneous vertebral augmentation Jin Liu1,2,4, Jing Tang3,4, Hao Liu1*, Zuchao Gu2, Yu Zhang2 & Shenghui Yu2 A convenient method to evaluate bone cement distribution following vertebral augmentation is lacking, and therefore so is our understanding of the optimal distribution. To address these questions, we conducted a retrospective study using data from patients with a single-segment vertebral fracture who were treated with vertebral augmentation at our two hospitals. Five evaluation methods based on X-ray flm were compared to determine the best evaluation method and the optimal cement distribution. Of the 263 patients included, 49 (18.63%) experienced re-collapse of treated vertebrae and 119 (45.25%) experienced new fractures during follow-up. A 12-score evaluation method (kappa value = 0.652) showed the largest area under the receiver operating characteristic curve for predicting new fractures (0.591) or re-collapse (0.933). In linear regression with the 12-score method, the bone cement distribution showed a negative correlation with the re-collapse of treated vertebra, but it showed a weak correlation with new fracture. The two prediction curves intersected at a score of 10. We conclude that an X-ray-based method for evaluation of bone cement distribution can be convenient and practical, and it can reliably predict risk of new fracture and re-collapse. The 12-score method showed the strongest predictive power, with a score of 10 suggesting optimal bone cement distribution. Since Galibert and Deramond frst used bone cement to treat aggressive cervical hemangiomas in 19871, this procedure has been verifed by numerous studies to be an efective minimally invasive surgery for the treatment of osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures (OVCFs)2–5. -

Vertebral Augmentation Involving Vertebroplasty Or Kyphoplasty for Cancer-Related Vertebral Compression Fractures: a Systematic Review

Health Quality Ontario The provincial advisor on the quality of health care in Ontario ONTARIO HEALTH TECHNOLOGY ASSESSMENT SERIES Vertebral Augmentation Involving Vertebroplasty or Kyphoplasty for Cancer-Related Vertebral Compression Fractures: A Systematic Review KEY MESSAGES Cancer can start in one part of the body and spread to other regions, often involving the spine, causing significant pain and reducing a patient’s ability to walk or carry out everyday activities such as bathing, dressing, and eating. When cancer spreads to or occurs in a bone of the spine (a vertebral bone), the cancer can weaken and break this bone. These fractures, if left untreated, can negatively affect the quality of life of terminally ill patients and their families. Vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty are two types of procedures called vertebral augmentation. During vertebral augmentation, the physician injects bone cement into the broken vertebral bone to stabilize the spine and control pain. Kyphoplasty is a modified form of vertebroplasty in which a small balloon is first inserted into the vertebral bone to create a space to inject the cement; it also attempts to lift the fracture to restore it to a more normal position. Medical therapy and bed rest are not very effective in cancer patients with painful vertebral fractures, and surgery is not usually an option for patients with advanced disease and who are in poor health. Vertebral augmentation is a minimally invasive treatment option, performed on an outpatient basis without general anesthesia, for managing painful vertebral fractures that limit mobility and self-care. We reviewed the evidence to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty in cancer patients. -

Stabilit™ Vertebral Augmentation System Redefining the Treatment Of

You would never guess that Janice had a Vertebral Compression Fracture. StabiliT™ For information about the StabiliT™ Vertebral Augmentation System, Vertebral Augmentation System Please visit www.dfineinc.com, or consult with your physician today. Redefining the treatment of Vertebral Compression Fractures 3047 Orchard Parkway San Jose, CA 95134 Tel: 1-866-96DFINE (1.866.963.3463) Fax: 408.321.9401 Email: [email protected] ©2008 DFine Inc. All rights reserved. PML1233-AA (09-2008) What is a Vertebral Compression Fracture? How the StabiliT™ Vertebral Augmentation StabiliT™ Vertebral Augmentation System System Works The spine is made up of a series of strong bones Redefining the treatment of Vertebral called vertebrae. A vertebra can break just like any StabiliT™ Vertebral Augmentation System is a Compression Fractures other bone in the body. When the vertebral body minimally invasive solution for treating vertebral The goal in treating a vertebral compression collapses, it is called a vertebral compression compression fractures of the spine to ease pain fracture is to stabilize it, reduce pain, return to and improve strength and stability of the fracture (VCF). normal function and prevent any spinal deformity. vertebral body. The StabiliT™ Vertebral Augmentation System This procedure is performed at a hospital under stabilizes the spine while providing patients with One fracture significantly local or general anesthesia. After making a small much needed pain relief. After treatment, studies increases the risk of incision, a small instrument is guided into the of minimally invasive vertebral augmentation another, causing spinal collapsed vertebra. procedures have shown: deformity and an overall decrease in health. VCFs are painful, sometimes • Relief of back pain and discomfort1 progressive and reduce • Potential correction of spinal deformity2 the patient’s quality of life. -

Spinal Surgery Coding Pain Coding

Spinal Surgery coding Pain Coding CASE STUDIES, DISCUSSION ROBIN INGALLS-FITZGERALD, CCS, CPC, FCS, CEDC, CEMC CEO/PRESIDENT MEDICAL MANAGEMENT AND REIMBURSEMENT SPECIALISTS, LLC Agenda Discuss spinal procedures CPT PCS And more Spinal Fusions- PCS coding Some of the most complex surgeries to code in ICD-10 Spinal fusion is classified by the anatomic portion (column) fused and the technique (approach) used to perform the fusion. The fusion can include a discectomy, bone grafting, and spinal instrumentation. Spinal Fusions Anterior Column: The body (corpus) of adjacent vertebrae (interbody fusion). The anterior column can be fused using an anterior, lateral, or posterior technique. Posterior Column: Posterior structures of adjacent vertebrae (pedicle, lamina, facet, transverse process, or “gutter” fusion). A posterior column fusion can be performed using a posterior, posterolateral, or lateral transverse technique. Approaches: Posterior or from the back (most common); anterior through a laparotomy Spinal Anatomy Devices Interbody fusion devices —e.g. BAK cages, PEEK cages, bone dowels Autologous Tissue Substitute —bone graft obtained from the patient during the procedure. Bone grafts may be harvested locally using the same incision, or from another part of the body requiring a separate incision. Harvesting requires a separate procedure code ONLY when it is performed through a separate incision. Nonautologous Tissue Substitute —bone bank Synthetic Substitute —examples include demineralized bone matrix, synthetic bone graft extenders, bone morphogenetic proteins (BMP) Interbody Fusion Devices The interbody fusion device immobilizes the intervertebral joint to stabilize the segment for fusion. It restores disc space height and requires removal of all or part of the disc so that the device can be inserted into the disc space. -

Kyphoplasty/Vertebroplasty, Thoracic Spine

Musculoskeletal Surgical Services: Spine Fusion/Stabilization Surgery; Kyphoplasty/Vertebroplasty, Thoracic Spine POLICY INITIATED: 06/30/2019 MOST RECENT REVIEW: 06/30/2019 POLICY # HH-5641 Overview Statement The purpose of these clinical guidelines is to assist healthcare professionals in selecting the medical service that may be appropriate and supported by evidence to improve patient outcomes. These clinical guidelines neither preempt clinical judgment of trained professionals nor advise anyone on how to practice medicine. The healthcare professionals are responsible for all clinical decisions based on their assessment. These clinical guidelines do not provide authorization, certification, explanation of benefits, or guarantee of payment, nor do they substitute for, or constitute, medical advice. Federal and State law, as well as member benefit contract language, including definitions and specific contract provisions/exclusions, take precedence over clinical guidelines and must be considered first when determining eligibility for coverage. All final determinations on coverage and payment are the responsibility of the health plan. Nothing contained within this document can be interpreted to mean otherwise. Medical information is constantly evolving, and HealthHelp reserves the right to review and update these clinical guidelines periodically. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without permission -

Spinal Instrumentation Rescue with Cement Augmentation

Published September 13, 2018 as 10.3174/ajnr.A5795 ORIGINAL RESEARCH SPINE Spinal Instrumentation Rescue with Cement Augmentation X A. Cianfoni, X M. Giamundo, X M. Pileggi, X K. Huscher, X M. Shapiro, X M. Isalberti, X D. Kuhlen, and X P. Scarone ABSTRACT BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE: Altered biomechanics or bone fragility or both contribute to spine instrumentation failure. Although revision surgery is frequently required, minimally invasive alternatives may be feasible. We report the largest to-date series of percuta- neous fluoroscopically guided vertebral cement augmentation procedures to address feasibility, safety, results and a variety of spinal instrumentation failure conditions. MATERIALS AND METHODS: A consecutive series of 31 fluoroscopically guided vertebral augmentation procedures in 29 patients were performed to address screw loosening (42 screws), cage subsidence (7 cages), and fracture within (12 cases) or adjacent to (11 cases) the instru- mented segment. Instrumentation failure was deemed clinically relevant when resulting in pain or jeopardizing spinal biomechanical stability. The main study end point was the rate of revision surgery avoidance; feasibility and safety were assessed by prospective recording of periprocedural technical and clinical complications; and clinical effect was measured at 1 month with the Patient Global Impression of Change score. RESULTS: All except 1 procedure was technically feasible. No periprocedural complications occurred. Clinical and radiologic follow-up was available in 28 patients (median, 16 months) and 30 procedures. Revision surgery was avoided in 23/28 (82%) patients, and a global clinical benefit (Patient Global Impression of Change, 5–7) was reported in 26/30 (87%) cases at 1-month follow-up, while no substantial change (Patient Global Impression of Change, 4) was reported in 3/30 (10%), and worsening status (Patient Global Impression of Change, 3), in 1/30 (3%).