An Artist- Scholar Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Faea-Fresh-Paint-Fall-2021.Pdf

FALL 2021 Volume 44 • Issue 2 The 2021 Annual What Affect Theory Conference Can Tell Us About Registration Becoming an Art Information Teacher and Schedule Preview Museum Spotlight: Orlando Museum of Art Tissue Vases Lesson Plan for Grades K-6 Royal & Langnickel Big Kids’ Choice Lil’ Grippers Deluxe Assorted Set of 6 Item #06082-1669 Blick Liquid Watercolors Item #00369 Transform plastic bottles and cups into colorful, textural containers for plants and flowers. Upcycle everyday objects to create 3D artwork! Using a mixture of water and medium, students layer strips of tissue paper to the outside of discarded plastic containers. Twist, bunch, and fold to create texture, then add color to create an earth-friendly vase. DickBlick.com/lesson-plans/Tissue-Vases-from-Recycled-Containers/ CHECK OUT NEW lesson plans and video workshops at DickBlick.com/lesson-plans. For students of all ages! Alliance for Young Artists ® Writers& Request a FREE 2021 Catalog! DickBlick.com/requests/bigbook2 Fresh Paint • FAEA Fall 2021 FALL 2021 • Volume 44 • Issue 2 C NTENTS features OUR COVER ARTIST NaTescha Holloway (Grade 8) Swimming with the Koi, 2021 FAEA K-12 Drawing Howard Middle School, Assessment & Teacher: Rachel Buckley Virtual Exhibition The purpose of this publication is to Winners | 13 provide information to members. Fresh Paint is a quarterly publication of Florida Art Education Association, Inc., located at 402 Office Plaza Drive, 2021 Annual Tallahassee, Florida 32301-2757. Conference Schedule FALL digital Preview | 18 Conference digital 13 Winter digital Remembering Spring/Summer digital Nellie Lynch | 25 FAEA 2021 Editorial Committee Lark Keeler (Chair) Jeff Broome What Affect Theory Susannah Brown Claire Clum Can Tell Us About departments Jackie Henson-Dacey Michael Ann Elliott Becoming an Art President’s Reflection | 4 Britt Feingold Heather I. -

Shifting Sands: Contemporary Trends in Powder Animation

Shifting Sands: Contemporary trends in powder animation Corrie Francis Parks1 1 University of Maryland, Baltimore Country, Visual Arts, 1000 Hilltop Circle, Baltimore, MD 21228, USA [email protected] Abstract. Backlit animation capitalizes on the purity of light pouring directly into the camera and no technique maximizes the nuances of that light better than sand animation. This paper will discuss the historical variations on sand animation, the physical properties of the material that result in typical movement patterns, and the contemporary evolution of the technique that break from the historical trends, due to the adoption of digital capture and compositing. Keywords: sand animation, hybrid animation, stopmotion, fluid frames 1 Introduction The mysterious art of powder animation is a technique to which I have deep personal connections as a practitioner, and one which represents the broader global trends of hybridization and handcrafted process in the animation field. This adoption of hybridity has brought a renewed interest to the technique, both for animator and for audiences. In this paper, I will give a brief overview of the technique and the common traits seen in historical and contemporary films that find their source in the unique properties of powdered material such as sand, salt, coffee and other dusts. Then I will discuss contemporary trends in the practice of this technique, based on new technology and accessibility. On occasion, I will speak generally about “sand animation” since this is the most common material in use, but the observations and conclusions apply to all powders used under the camera. The source of this research is from my own practice as an independent filmmaker cross-referenced with historical investigation and interviews with contemporary artists practicing powder animation techniques. -

Narrative Strategies in the Creation of Animated Poetry-Films

Narrative strategies in the creation of animated poetry-films by Georg Diederik Grobler Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the subject of ART In the DEPARTMENT OF ART AND MUSIC at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA PROMOTOR: Professor Elfriede Dreyer DATE: February 2021 Declaration I declare that Narrative strategies in the creation of animated poetry-films is my own work and that all the sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged using complete references. I further declare that I submitted the thesis to originality checking software and that it falls within the accepted requirements for originality. I further declare that I have not previously submitted this work, or part of it, for examination at Unisa for another qualification or at any other higher education institution. 20 February 2021 ii Summary This doctoral study investigates the practice of narrative strategies in the creation of animated poetry-film. The status of the animator as auteur of the poetry-film is established on the grounds of the multiple instances of additional authoring that the animated poetry-film requires. The study hypothesises that diverse narrative strategies are operative in the production of animated poetry-film. Two diametrically opposed strategies are identified as ideal for the treatment of lyrical narrative. The first narrative strategy explored is that of metamorphosis, demonstrating how the filmic material originates and grows organically via stream of consciousness and free association. The second narrative strategy entails a calculated approach of structuring visual imagery and meaning through editing from a pre-existing visual lexicon. -

Allison Schulnik's Hobo Clown

Allison Schulnik’s Hobo Clown: grotesque resistance, storytelling metamorphosis and Franz Kafka by william boyd fraser, sculptor A Major Research Paper presented to OCAD University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Contemporary Art, Design and New Media Art Histories Toronto, Ontario, Canada, April, 2015 © william boyd fraser, 2015 ii Author’s Declaration i hereby declare that i am the sole author of this thesis. this is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final versions, as accepted by my examiners. i authorize OCAD University to lend this thesis to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. i understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. i further authorize OCAD University to reproduce this thesis by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. iii Abstract Allison Schulnik’s Hobo Clown clay stop-motion film is analyzed using a rhetorical triangulation of persuasion. A hybrid method alternates Schulnik, reader and an imaginary Other for three points of view providing comparisons of story perspective. Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis provides an exemplary third person narrative style. A history of stop-motion animation, hobos and clowns, along with animation theory of metamorphosis contribute to a hypothetical null questioning of Schulnik’s grotesque as a constructive identity resisting expectation. Mise-en-scène of staging and music provide sensory, visual and auditory description along with primary source materials and theoretical insight for describing a reading of the film’s grotesque transformations. -

Venue Partner Supported By

Venue partner Supported by The Film & Video Workshop is an educational charity dedicated to helping people make animation and films We have 17 years of experience working in the film industry from our purpose-built London studio stop motion after effects animation animation techniques puppet making courses AE BAFTA winning tutor • specialists in animation • 17 years of teaching experience video production intensive video production taster production courses courses from as little as £55 craft of editing avid introduction nal cut pro beginners post-production nal cut pro advanced nal cut pro X dvd studio pro courses booking@filmworkshop.com www.filmworkshop.com 020 7607 8660 Directors Message Here we go again – another year, another festival. Time never seems to stand still at LIAF HQ, though sometimes we wish it did. Writing this introduction to the festival is like a sort-of taking stock for me. A time to reflect on the year that’s been. Moving LIAF two months later in the year (and into ‘festival season’ as everyone keeps telling me) is probably the biggest change for us this year. Out of late Summer and into early Autumn, where the nights are drawing in. Will that mean more people will be wanting to gather inside the warm, darkened spaces of the cinema? Let us see. We hope so, for once again we have scoured the globe and feasted on 2,300 + little animated gems from around the world in order to craft the festival that you see before your beady eyes. 277 films from 36 countries, and the usual broad mix of everything from scratch films, pinscreen, time-slice, live-action/animation hybrids, puppet, clay, drawn, scribbled and a whole lotta’ “how the hell have they done that?” films. -

Origins of American Animation 1. What Is The

!1. WEB SITE RESEARCH Topic research: Origins of American Animation 1. What is the educational benefit of the information related to your topic? The educational benefit of the information related to my topic is that the viewer can understand the origins of American Animation how it started, how it began, and why did we move toward animation. The information is educational because it gives a history on how American animation began compared to what modern day animation is. !2. What types of viewers will be interested in your topic? ! Animators, illustration artists, and arts majors would be interested in the origins of American animation because of the ties it has to their career or interests. Filmographies and directors would also be interested in the topic because its what they do, storytelling through the use of visuals. Possibly even photographers because the start of animation was the combinations of photos run through a slide to create a moving image. 3. What perceived value will your topic give to your viewers? The viewers will gain knowledge from learning about the origins of American animation and how it began. This information could be used to understand their interests and how it came to be. The viewers will gain value by also watching the animation videos that were made from the beginning. Origins of American Animation are a collection of 21 animated films and 2 fragments. The collection features films that are clay, puppet, and cut-out animation, as well as pen drawings. !4. Primary person(s) of significance in the filed of your topic? A primary person that had significance in the field of animation was George Méliès who had demonstrated in 1896 that objects could be set in motion through single-frame exposures. -

Secrets of Oscar-Winning Animation Sample Chapter.Pdf

Like what you see? Buy the book at the Focal Bookstore Secrets of Oscar-winning Animation Cotte ISBN 978-0-240-52070-4 Mona Lisa descending a staircase Through the transformation of famous pieces of art, the film offers a panorama of painting from the end of the nineteenth century to the present day. Using incomparable technical and artistic skill, it creates a explosive display of colors, textures and clues, for the amateur to decipher, as to the indentify of the work. The screenplay relies on the pleasure experienced upon seeing the chosen works, and the intelligence of the associations as well as the way they are linked in the film. Oscar 1992 Joan C. GRATZ 161 Clay painting Credits descriptive Title: Mona Lisa descending a staircase Year: 1991 Country: United States Director: Joan C. Gratz Production: Gratzfilm Screenplay, animation, artwork, layout, storyboard: Joan C. Gratz Technique used: Clay painting Music: Jamie Haggerty Sound: Chel White Voice and didgeridoo: Jean G. Poulot The transformation is applied to the film’s symbol (Mona Lisa) Sound mix: Lance Limbocker to create the title sequence. Optical printing: Fred Pack Length: 7 minutes Joan C. Gratz received degrees in painting from the University of California at Los Angeles and in architecture at the University of Oregon. She developed her technique of animated painting when she was an architecture student, then shifted to clay while working with Will Vinton Studios from 1976 to 1987. During that time, her work included design and animation for the Academy Award nominated film Return to Oz by Disney. Short film nominees Rip Van winkle and The Creation, which was the first film to feature Joan’s clay painting. -

Case Pikku Kakkonen

Creating Animated Stickers for Social Media Platforms Using Brand-Based Imagery – Case Pikku Kakkonen Sofi-Ilona Löhönen BACHELOR’S THESIS April 2020 Degree Programme in Media and Arts Fine Art 2 ABSTRACT Tampereen ammattikorkeakoulu Tampere University of Applied Sciences Degree Programme in Media and Arts Fine Art LÖHÖNEN, SOFI-ILONA: Creating Animated Stickers for Social Media Platforms Using Brand-Based Imagery Case Pikku Kakkonen Bachelor's thesis of 67 pages April 2020 Animation is an adaptable medium. In digital media, animation can be detected for example in the form of GIF. Today GIFs are used in multiple ways, such as a decorative, promotional and artistic elements, as well as communicational tools – for example as animated stickers – on personal messaging platforms. The purpose of this thesis was to create animated stickers, and two animated shorts for Pikku Kakkonen, which were set to be used in social media platforms as decorative elements and updates. Pikku Kakkonen is a magazine-styled Finnish children’s program. The program’s Art Director Elli Murtonen had a vision to add elements into Pikku Kakkonen’s Instagram by launching a set of stickers using the brand’s visual brand imagery. The research was carried out in order to study how animation, its principles and production works, and how it is being adapted as a medium. The thesis also explored the history and the technical functionality of the GIF, and how the format was used in social media. These findings were aimed at being utilized in the thesis project, focusing on important matters when creating animations using Pikku Kakkonen’s vector graphics, while simultaneously aiming to adapt the animation principles. -

JOANNA PRIESTLEY: Joanna Priestley’S Amazing Body of Animated Films Have Deservedly Earned Their Place in the Pantheon of Contemporary International Animators

"Priestley gets across a series of personal phobias in a refreshing and humorous fashion. We get a superb, contemporary animated film with salutes to historical cartoon figures scattered throughout. Delightful!" – Marv Newland, Northwest Film and Video Festival Juror. ABOUT THE ARTIST Joanna Priestley studied painting and printmaking at Rhode Island School of Design and at UC Berkeley, where she received a Bachelor of Arts Degree with Honors. She also attended California Institute of the Arts where she received an MFA Degree and the Louis B. Mayer Award. Her background includes Coordinator of the Northwest Film and Video Festival, Director of Strictly Cinema, Editor of "The Animator", Regional Coordinator of the Northwest Film Center, Co-Director and Co-Founder of FILMA: Women's Film Forum and founding President of ASIFA Northwest. Priestley teaches animation workshops worldwide and she has run an apprenticeship program since 1986. She has served on numerous juries and selection committees, including Stuttgart International Animation Festival, Canadian International Animation Festival, Texas Filmmakers Production Fund, Big Muddy Film Festival and the Annie Awards. Priestley also enjoys medicinal herbalism, gardening and Burning Man. Her films are available at www.primopix.com and www.microcinema.com . In Joanna Priestley’s beautiful film, each frame is alive with invention, possibility and delight. – Richard Peña, New York Film Festival Joanna Priestley is one of the most interesting and adept personal animators and filmmakers. I have enjoyed her work for years and been amazed at how she gets into her own thoughts into the screen in a very elegant and focused way. – Gus Van Sant JOANNA PRIESTLEY: Joanna Priestley’s amazing body of animated films have deservedly earned their place in the pantheon of contemporary international animators. -

Cell Animation

CELL ANIMATION Even though animation was conceived as early as 1824 by Peter Roget, the very first actual methods of animation were made possible by a device called a zoetrope. The zoetrope was a spinning cylinder with open slits that would allow viewing of certain still images in a certain sequence. Someone viewing a zoetrope at a particular angle could see images that appeared to be moving. After Edison and the invention of motion pictures in 1889, film director Emile Cohl combined more than 700 still drawings, which were then each meticulously photographed individually. When Cohl combined all of the shots together, the drawings appeared to be moving on the film, "Fantasmagorie," which was released in 1908. Other animated films soon followed like "Gertie the Dinosaur" and "Felix the Cat," both released around 1920. Max Fleischer had next invented a device known as the rotoscope, which allowed animators to trace over live action film frame by frame onto an animation cel. Max and Dave Fleischer created the first sound cartoon, "Song Car Tunes" in 1924, three years before the first talking motion picture. Walt and Roy Disney perfected the rotoscope technique and opened their Disney Brothers Cartoon Studio in 1923. They created the first cartoon with a synchronized soundtrack titled "Steam Boat Willy," which also introduced Mickey Mouse to the world in 1928. The Disney studio also created the first color full-color animated cartoon titled, "Flowers and Trees" in 1932. However, it would be the Disney studio's first full-length animated feature movie that would be remembered by most people as the most recognized cartoon in animation history: "Snow White and the Seven Dwarves." The animated cartoon movie earned $8 million for Disney and was the beginning of the Disney empire. -

Contribución De La Animación Cinematográfica, Al Desarrollo Del Trucaje Cinematográfico Y Los Efectos Especiales En El Cine Contemporáneo

Universidad Politécnica de Valencia Departamento de Dibujo TESIS DOCTORAL Contribución de la animación cinematográfica, al desarrollo del trucaje cinematográfico y los efectos especiales en el cine contemporáneo. Presentada por D. Miguel Vidal Ortega Dirigida por Dra. Dña Carmen Lloret Ferrándiz 2008 Especialmente a Nary, mi esposa y a mi pequeña Lorena La real posibilidad de realizar y concluir la presente investigación, se debe en primera instancia a la gentil invitación personal hecha por la Dra. Dña. Carmen Lloret Ferrándiz y a la Dirección correspondiente del Departamento de Dibujo de la Facultad de Bellas Artes de esta Universidad, para realizar desde Cuba, este proyecto de tesis doctoral. Agradezco infinitamente la confianza depositada y las facilidades ofrecidas para poder llevar a cabo nuestro trabajo. En primer lugar a Carmen Lloret, Directora de esta tesis, por su clarificadora dirección, orientando desde el primer momento la investigación por las mejores vías y hacia los propósitos más adecuados. Su continua supervisión y asesoramiento han sido vitales para la conclusión de la presente tesis doctoral. Deseo expresar mi más profundo y sincero agradecimiento por ello. Muy especialmente al Dr. D. Víctor Manuel Gimeno Baquero, Catedrático Emérito de la misma Facultad, por sus consejos, aciertos y recomendaciones al abordar el tema, simplemente en conversaciones y amenas charlas, al resto del colectivo de profesores de la unidad de Animación, amigas y colegas, Sara, Mª Ángeles, Susana y Maria, por su apoyo en todo momento, brindándome fuerza, aliento y tesón para lograr mi empeño. A todas las compañeras del Departamento de Dibujo y a su Director Dr. D. Miguel Ángel Guillem Romeu por acogerme y mediar con verdadera complicidad y humanismo en cada una de las etapas para el desarrollo de mi candidatura. -

Demeber-2010-Issue.Pdf

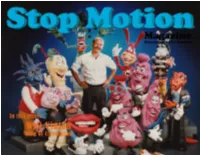

John Ikuma - Executive Editor / Layout / Writer Melissa Piekaar - Editor Pike Baker - Writer Cara Zambri - Contributing Writer Letter From the Editor: In this issue you will a great interview with the legendary Will Vinton. Mr. Vinton was kind enough to talk to us about his life and career as one of the major influences in our industry. We owe him a huge thank you for granting us the opportunity to talk with him. We hope you will feel as inspired as much as we do from his words of wisdom. On another note, I am currently playing catch up with this issue. Though this is marked as the December Issue, it is actually being released in late January for a number of reasons. The first reason is since this is such a small publication with only a few contributors; I am faced with most of the responsibility for produc- ing it. This involves many many hours of work. Since there are so few advertisers I must spend most of my available time dedicated to my Visual Effects Company and often this means hours of animating and bring in income to pay the bills. I’m not complaining about getting work though in these hard times. Also, being privileged enough to be paid to do what I love is a dream come true. But what I’m really saying is, sorry for the delay. We should be completely caught up by the end of February and back on schedule. The crew and I would like to thank you very much for your support and dedication as readers and we hope to provide you with more is- sues for years to come.