Nature Photography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vermilion Cliffs

2014 Manager’s Manager’s Annual Report Vermilion Cliffs National Monument Manager’s Annual Report FY 2014 Arizona Table of Contents 1 Vermilion Cliffs Profile 2 2 Planning and NEPA 5 3 Year’s Projects and Accomplishments 6 4 Science 10 5 Resources, Objects, Values, and Stressors 11 Summary of Performance Measures 20 6 7 Manager’s Letter 21 1 Vermilion Cliffs Profile 1 Designating Authority Designating Authority: Presidential Proclamation Date of Designation: November 9, 2000 If other legislation exists that has affected the management of the unit, list it here as well. N/A Acreage Total Acres in Unit BLM Acres Other Fed. Acres State Acres Other Acres 293,687 279,566 0 13,438 683 (private) Contact Information Unit Manager Phone E-mail Mailing Address Kevin Wright 435-688-3241 [email protected] 345 E Riverside Dr. St. George, UT 84790 Field Office District Office State Office Arizona Strip Arizona Strip AZ Budget Total FY14 Budget Subactivity 1711 Other Subactivities’ Other Funding Contributions 789,359 376,009 413,350 2 Map of Vermilion Cliffs National Monument 3 Managing Partners If an outside group or a non-BLM agency (like the Park or Forest Service) formally helps to manage the unit, please describe them in this section. If BLM is the sole official manager of the unit, simply enter “N/A.” Regular partnerships and partner activities are covered in a later section of this report. N/A Staffing How is the unit’s work accomplished? Does it have its own dedicated manager and staff? Does it share staff with another unit, BLM office, or other Federal agency? Summarize the types (e.g., job series) and numbers of staff members. -

Arizona, Road Trips Are As Much About the Journey As They Are the Destination

Travel options that enable social distancing are more popular than ever. We’ve designated 2021 as the Year of the Road Trip so those who are ready to travel can start planning. In Arizona, road trips are as much about the journey as they are the destination. No matter where you go, you’re sure to spy sprawling expanses of nature and stunning panoramic views. We’re looking forward to sharing great itineraries that cover the whole state. From small-town streets to the unique landscapes of our parks, these road trips are designed with Grand Canyon National Park socially-distanced fun in mind. For visitor guidance due to COVID19 such as mask-wearing, a list of tourism-related re- openings or closures, and a link to public health guidelines, click here: https://www.visitarizona. com/covid-19/. Some attractions are open year-round and some are open seasonally or move to seasonal hours. To ensure the places you want to see are open on your travel dates, please check their website for hours of operation. Prickly Pear Cactus ARIZONA RESOURCES We provide complete travel information about destinations in Arizona. We offer our official state traveler’s guide, maps, images, familiarization trip assistance, itinerary suggestions and planning assistance along with lists of tour guides plus connections to ARIZONA lodging properties and other information at traveltrade.visitarizona.com Horseshoe Bend ARIZONA OFFICE OF TOURISM 100 N. 7th Ave., Suite 400, Phoenix, AZ 85007 | www.visitarizona.com Jessica Mitchell, Senior Travel Industry Marketing Manager | T: 602-364-4157 | E: [email protected] TRANSPORTATION From east to west both Interstate 40 and Interstate 10 cross the state. -

Paria Canyon Vermilion Cliffs Wilderness Management Plan

01\16• ,.J ~ UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR -- BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT ~Lf 1.,.J/ t'CI/C w~P 0 ARIZONA STRIP FIELD OFFICE/KANAB RESOURCE AREA PARIA CANYONNERMILION CLIFFS WILDERNESS MANAGEMENT PLAN AMENDMENT ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT EA-AZ-01 0-97-16 I. INTRODUCTION The Paria Canyon - Vermilion Cliffs Wilderness Area contains 112,500 acres (92,500 acres in Coconino County, Arizona and 20,000 acres in Kane County, Utah) of public lands managed by the Bureau of Land Management. The area is approximately 10 to 30 miles west of Page, Arizona. Included are 35 miles of the Paria river Canyon, 15 miles of the Buckskin Gulch, Coyote Buttes, and the Vermilion Cliffs from Lee's Ferry to House Rock Valley (Map 1). The Paria Canyon, Buckskin Gulch, Wire Pass, and the Coyote Buttes Special Management Area are part of the larger Paria Canyon-Vermilion Cliffs Wilderness, designated in August 1984 (Map 2). Existing management plan guidance is to protect primitive, natural conditions and the many outstanding opportunities for hiking, backpacking, photographing, or viewing in the seven different highly scenic geologic formations from which the canyons and buttes are carved. Visitor use in Paria Canyon, Buckskin Gulch, and Coyote Buttes has increased from 2,400 visits in Fiscal Year (FY) 1986 to nearly 10,000 visits in FY96-a 375% increase in use over 10 years. This increased use, combined with the narrow nature of the canyons, small camping terraces, and changing visitor use patterns, is impacting the wilderness character of these areas. Human waste, overcrowding, and public safety have become important issues. -

1 Uphill-Only Dinosaur Tracks? a Talking Rocks 2017 Participant

1 Uphill-only Dinosaur Tracks? A Talking Rocks 2017 Participant Seeks Answers Robert T. Johnston Talking Rocks 2017 was a geology tour organized by Adventist pastor John McLarty and guided by Gerald Bryant, an Adventist geology professor at Dixie State University (St. George, UT) and an expert in the sedimentary geology of the area—in particular, the extensive sandstone outcrops of the geologic unit formally known as the Navajo Sandstone. I had the pleasure of participating in the first Talking Rocks tour last year and enjoyed the experience so much that I went again this year! Two other participants from 2016 also repeated. New participants included a mix of men and women of varied backgrounds and points of view on the age of the earth and “Flood geology”, and two children. Besides Bryant, none of us had formal geology backgrounds, but we were eager to learn more about geology and the intersection of faith and science. We converged on St. George, Utah, from where we traveled to various sites in Utah and northern Arizona. Places not visited last year included the Pine Valley Mountains, new sites in Snow Canyon, and a hike to what locals call the Vortex, an amazing area where a complex stack of ancient, trough-shaped dune deposits is dissected by the modern canyons. The topography features an enormous vortex-shaped “scour pit”1 at the top of a ridge, where sand grains loosened by weathering are removed by wind currents sweeping the landscape (Figure 1). Figure 1. Talking Rocks organizer John McLarty making his way into the Vortex, a weathered and eroded Navajo Sandstone feature north of St. -

Directions to Hiking to Coyote Buttes & the Wave

Coyote Buttes/The Waves Ron Ross December 22, 2007 Coyote Buttes is located in the Paria Canyon-Vermilion Cliffs Wilderness just south of US¶89 about halfway between Kanab, Utah and Page, Arizona. The wilderness area sits on the border between Arizona and Utah and is managed by the BLM. It is divided into two areas: Coyote Buttes North and Coyote Buttes South. To visit either of the Coyote Buttes areas you will need to purchase a hiking permit in advance (see https://www.blm.gov/az/paria/index.cfm?usearea=CB). Only 20 people per day (10 advanced reservations and 10 walk-ins) are allowed to hike in, and separate permits are required for the North and South sections. The walk-in permits can be acquired off the web, from the BLM office in Kanab, or from the Paria Ranger Station near the Coyote Buttes. The Northern section of Coyote Buttes is by far the most popular, as it contains the spectacular sandstone rock formations, pictured below, known as the Wave and the Second Wave. As a result of their popularity, getting permits for the Northern section is very competitive and often results in a lottery to select the lucky folks for a particular day. The Southern section also contains some outstanding sandstone formations known as the Te- pees. However, the road to the southern section can be very sandy and challenging, even for high- clearance 4x4 vehicles. As a result, walk-in permits for the Southern section are widely available. COYOTE BUTTES NORTH—THE WAVE Trailhead The hike to the wave begins at the Wire Pass Trailhead about 8 miles south of US¶89 on House Rock Valley Road. -

Sheeting Joints and Polygonal Patterns in the Navajo Sandstone, Southern Utah: Controlled by Rock Fabric, Tectonic Joints, Buckling, and Gullying David B

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Papers in the Earth and Atmospheric Sciences Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Department of 2018 Sheeting joints and polygonal patterns in the Navajo Sandstone, southern Utah: Controlled by rock fabric, tectonic joints, buckling, and gullying David B. Loope University of Nebraska, Lincoln, [email protected] Caroline M. Burberry University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/geosciencefacpub Part of the Earth Sciences Commons Loope, David B. and Burberry, Caroline M., "Sheeting joints and polygonal patterns in the Navajo Sandstone, southern Utah: Controlled by rock fabric, tectonic joints, buckling, and gullying" (2018). Papers in the Earth and Atmospheric Sciences. 519. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/geosciencefacpub/519 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers in the Earth and Atmospheric Sciences by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Research Paper GEOSPHERE Sheeting joints and polygonal patterns in the Navajo Sandstone, southern Utah: Controlled by rock fabric, tectonic joints, buckling, GEOSPHERE, v. 14, no. 4 and gullying https://doi.org/10.1130/GES01614.1 David B. Loope and Caroline M. Burberry 14 figures; 1 table Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, University of Nebraska, -

Arizona Strip Visitor Map Arizona

/ •/ Jte A^ [?*"tfi L' h / P t JEM' • t£ L, OURMiSSION We serve customers from around the corner and around the world by integrating growing public needs with traditional uses on the remote public lands &z^Bflfch — north of the Grand Canyon. / ADDRESSES & WEBSITES BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT —ARIZONA PUBLIC LANDf A • (-t • r-A- , • , A-\rr- i i r ,• r~ Collared llizari d Arizona atrip District Ottice and Information Center Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument 345 E. Riverside Drive, St. George, UT 84790 Phone (435) 688-3200/3246 http://www.blm.gov/az/asfo/index.htm Arizona Strip Interpretive Association (ASIA) 345 E. Riverside Drive, St. George, UT 84790 Phone (435) 688-3246 http://www.thearizonastrip.com —UTAH PUBLIC LANDS— St. George Field Office and Information Center 345 E. Riverside Drive, St. George, UT 84790 Phone (435) 688-3200 http://www.ut.blm.gov/st_george Kanab Field Office 318 N. 100 E.,Kanab, UT 84741 ,« Visitor Map Phone (435) 644-4600 O.vJU http://www.ut.blm.gov/kanab 2DQfj Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument 190 E. Center Street, Kanab, UT 84741 Phone (435) 644-4300/4680 (visitor information) http://www.ut.blm.gov/spotgse.html FOREST SERVICE North Kaibab Ranger District 430 South Main, Fredonia, AZ 86022 Phone (928) 643-7395 http://www.fs.fed.us/r3/kai NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Grand Canyon National Park P.O. Box 129, Grand Canyon, AZ 86023 Phone (928) 638-7888 http://www.nps.gov/grca Lake Mead National Recreation Area 601 Nevada Way, Boulder City, NV 89005 Phone (702) 293-8990 http://www.nps.gov/lame View from Black Rock Mountain, AZ Glen Canyon National Recreation Area P.O.Box 1507, Page, AZ 86040 FOR EMERGENCIES, CALL: Phone (928) 608-6404 http://www.nps.gov/glca Washington County, UT 91 1 or (435) 634-5730 Kane County, UT 91 1 or (435) 644-2349 Pipe Spring National Monument 406 N. -

Paria Canyon Vermilion Cliffs Wilderness

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT ARIZONA STRIP FIELD OFFICE/KANAB RESOURCE AREA DECISION RECORD DR-AZ-010-98-03 MANAGEMENT OF RECREATION IN THE PARIA CANYON - VERMILION CLIFFS WILDERNESS The Paria Canyon - Vermilion Cliffs Wilderness Area contains 112,500 acres of public lands managed by the Bureau of Land Management. The area is approximately 10 to 30 miles west of Page, Arizona. Included are 35 miles of the Paria River Canyon, 15 miles of the Buckskin Gulch, Coyote Buttes, and the Vermilion Cliffs from Lee's Ferry to House Rock Valley. The Paria Canyon, Buckskin Gulch, Wire Pass, and the Coyote Buttes Special Management Area are part of the larger Paria Canyon-Vermilion Cliffs Wilderness, designated in August 1984. Visitor use has increased from 2,400 visits in Fiscal Year (FY) 1986 to nearly 10,000 visits in FY96-a 375% increase in use over 10 years. This increased use, combined with the narrow nature of the canyons, small camping terraces, and changing visitor use patterns, is impacting the wilderness character of these areas. Human waste, overcrowding, and public safety have become significant issues. The purpose of this action is to establish guidelines and implement management actions related to recreational use of the Paria CanyonNermilion Cliffs Wilderness Area. An increase in recreational use in the wilderness has caused degradation of sensitive resources. On pag~ 8, the plan states that BLM will "initiate a system to regulate recreation use if monitoring demonstrates a need to limit user numbers. A study of alternative a/location techniques, including fees, will be prepared and analyzed in an environmental assessment involving public participation. -

Vermilion Cliffs National Monument Resources Summary

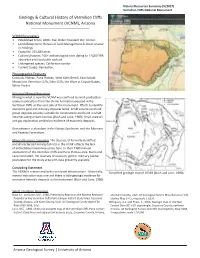

Natural Resources Summary (5/2017) Vermilion Cliffs National Monument Geology & Cultural History of Vermilion Cliffs National Monument (VCNM), Arizona ____________________________________ VCNM Parameters • Established 9 Nov. 2000 - Exe. Order President W.J. Clinton • Land Mangement: Bureau of Land Management & minor private in-holdings • Footprint: 293,689 acres • Cultural features: 100+ archaeological sites dating to 12,000 YBP, abundant and invaluable rock-art. • Endangered species: Californian condor • Current Use(s): Recreation, Physiographic Features Colorado Plateau, Paria Plateau, West Clark Bench, East Kaibab Monocline, Vermilion Cliffs, Echo Cliffs, the Wave at Coyote Buttes, White Pocket. Historical Mineral Resources Mining in what is now the VCNM was confined to small production uranium extraction from the Chinle Formation exposed in the Vermilion Cliffs on the east side of the monument. Efforts to identify economic gold and mercury deposits failed. Small volume sand and gravel deposits possibly suitable for construction are found in small volumes along stream courses (Bush and Lane, 1980). Small scale oil and gas exploration yielded no evidence of economic deposits. Groundwater is abundant in the Navajo Sandstone and the Moenave and Kayenta Formations. Mineral Resource Summary. The absence of formally identified and characterized mining districts in the VCNR reflects the lack of extractable mineral resources here. In their 1980 mineral assessment of the Vermilion Cliffs and Paria Plateau area, Burns and Lane concluded, ‘No reserves of uranium, gold or mercury can be postulated for the study area with data presently available.’ Concluding Statement. The VCNM is remote and lacks even basic infrastructure. Historically, Simplified geologic map of VCNM (Bush and Lane, 1980). -

Business Plan

Paria Canyon/Coyote Buttes Special Management Area Business Plan United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management Arizona Strip Field Office, Vermilion Cliffs National Monument Kanab Field Office Grand Staircase – Escalante National Monument Arizona Strip Interpretive Association Northern Arizona University July 2008 The famous “Wave” in Coyote Buttes Table of Contents I. Executive Summary .....................................................................................................1 II. Special Management Area Description ......................................................................4 A. Physical Description ...............................................................................................4 B. Administration ........................................................................................................4 C. Area Features ..........................................................................................................4 D. Area Management .................................................................................................10 E. Commercial Use .................................................................................................. 11 F. Fee Demonstration History ...................................................................................12 G. Partnerships ...........................................................................................................12 H. General Management Concerns ............................................................................13 -

Federal Register/Vol. 63, No. 25/Friday, February 6, 1998/Rules

Federal Register / Vol. 63, No. 25 / Friday, February 6, 1998 / Rules and Regulations 6075 reasonableness of state action. The for judicial review may be filed, and DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Clean Air Act forbids EPA to base its shall not postpone the effectiveness of actions concerning SIPs on such such rule or action. This action may not Bureau of Land Management grounds. Union Electric Co. v. U.S. EPA, be challenged later in proceedings to 427 U.S. 246, 255±66 (1976); 42 U.S.C. enforce its requirements. (See section 43 CFR Parts 8560 and 8372 7410(a)(2). 307(b)(2).) [AZ±010±01±1210±04] C. Unfunded Mandates List of Subjects in 40 CFR Part 52 Paria Canyon-Vermilion Cliffs Under Section 202 of the Unfunded Environmental protection, Air Wilderness, AZ±UT: Visitor Rules Mandates Reform Act of 1995 pollution control, Hydrocarbons, (``Unfunded Mandates Act''), signed Incorporation by reference, AGENCY: Bureau of Land Management, into law on March 22, 1995, EPA must Intergovernmental relations, Ozone, Interior. prepare a budgetary impact statement to Reporting and recordkeeping ACTION: Notice of intent to implement accompany any proposed or final rule requirements, Volatile organic recreation permit requirements. that includes a Federal mandate that compounds. may result in estimated costs to State, SUMMARY: The Bureau of Land local, or tribal governments in the Note: Incorporation by reference of the Management (BLM) has revised visitor aggregate; or to private sector, of $100 State Implementation Plan for the State of rules for the Paria Canyon, Buckskin California was approved by the Director of million or more. -

United States Department of the Interior

United States Department of the Interior BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT Arizona Strip District Vermilion Cliffs National Monument 345 East Riverside Drive St. George, Utah 84790 http://www.blm.gov/az/ Phone (435) 688-3200 • Fax (435) 688-3258 In Reply Refer To: 6340/6360 (LLAZA02000) May 8, 2019 NOTICE OF PUBLIC SCOPING PROPOSED CHANGE IN MANAGEMENT OF THE PARIA CANYON-VERMILION CLIFFS WILDERNESS AND OTHER RELATED ACTIONS Dear Interested Party, Please be advised that an Environmental Assessment (EA) will be prepared to disclose the potential environmental impacts for a proposed change in management ofthe Paria Canyon-Vermilion Cliffs Wilderness. The purpose ofthis letter is to help the BLM identify issues that should be considered in the EA and to invite comments on this proposed project in terms of any issues, reso~rces, or uses that should be considered in preparing this EA. This letter will also assist the BLM in learning who is interested in this proposed project and wishes to be informed when the EA may be available for public review and comment. The Paria Canyon-Vermilion Cliffs Wilderness Management Plan (WMP) was originally developed in 1987, and was amended in 1998 in order to establish daily visitor use limits for Coyote Buttes North, Coyote Buttes South, and Paria Canyon/Buckskin Gulch to preserve wilderness character, including naturalness, outstanding opportunities for solitude, and outstanding opportunities for primitive and unconfined recreation. In recent years, there has been a dramatic increase in public demand to visit these areas, in particular to Coyote Buttes North (where the feature known as "The Wave" is located).