CONTENTS Page

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![County Londonderry - Official Townlands: Administrative Divisions [Sorted by Townland]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6319/county-londonderry-official-townlands-administrative-divisions-sorted-by-townland-216319.webp)

County Londonderry - Official Townlands: Administrative Divisions [Sorted by Townland]

County Londonderry - Official Townlands: Administrative Divisions [Sorted by Townland] Record O.S. Sheet Townland Civil Parish Barony Poor Law Union/ Dispensary /Local District Electoral Division [DED] 1911 D.E.D after c.1921 No. No. Superintendent Registrar's District Registrar's District 1 11, 18 Aghadowey Aghadowey Coleraine Coleraine Aghadowey Aghadowey Aghadowey 2 42 Aghagaskin Magherafelt Loughinsholin Magherafelt Magherafelt Magherafelt Aghagaskin 3 17 Aghansillagh Balteagh Keenaght Limavady Limavady Lislane Lislane 4 22, 23, 28, 29 Alla Lower Cumber Upper Tirkeeran Londonderry Claudy Claudy Claudy 5 22, 28 Alla Upper Cumber Upper Tirkeeran Londonderry Claudy Claudy Claudy 6 28, 29 Altaghoney Cumber Upper Tirkeeran Londonderry Claudy Ballymullins Ballymullins 7 17, 18 Altduff Errigal Coleraine Coleraine Garvagh Glenkeen Glenkeen 8 6 Altibrian Formoyle / Dunboe Coleraine Coleraine Articlave Downhill Downhill 9 6 Altikeeragh Dunboe Coleraine Coleraine Articlave Downhill Downhill 10 29, 30 Altinure Lower Learmount / Banagher Tirkeeran Londonderry Claudy Banagher Banagher 11 29, 30 Altinure Upper Learmount / Banagher Tirkeeran Londonderry Claudy Banagher Banagher 12 20 Altnagelvin Clondermot Tirkeeran Londonderry Waterside Rural [Glendermot Waterside Waterside until 1899] 13 41 Annagh and Moneysterlin Desertmartin Loughinsholin Magherafelt Magherafelt Desertmartin Desertmartin 14 42 Annaghmore Magherafelt Loughinsholin Magherafelt Bellaghy Castledawson Castledawson 15 48 Annahavil Arboe Loughinsholin Magherafelt Moneymore Moneyhaw -

The Full Details of Following Planning Applications Including Plans, Maps

Cloonavin, 66 Portstewart Road, Coleraine, BT52 1EY Tel +44 (0) 28 7034 7034 Web www.causewaycoastandglens.gov.uk Planning Applications The full details of following planning applications including plans, maps and drawings are available to view on the NI Planning Portal www.planningni.gov.uk or at the Council Planning Office or by contacting 028 7034 7100. Written comments should be submitted within the next 14 days. Please quote the application number in any correspondence and note that all representations made, including objections, will be posted on the NI Planning Portal. David Jackson Chief Executive APPLICATION LOCATION BRIEF DESCRIPTION Initial Adv BALLYMONEY LA01/2018/0328/F 17 Drumbane Rd, CloughmillsExtension to dwelling. LA01/2018/0339/O 158m SE of 243 Garryduff Rd,Site of dwelling & garage on Dunloy. a farm. Re-Adv LA01/2017/1251/F 59 Taughey Rd & land to Housing development of 4 the rear of 57a Taughey Rd no. semi-detached & 1 no. Balnamore Ballymoney. detached dwellings. Initial Adv BANN LA01/2018/0326/F Lands at Craigall Quarry , Retention of existing Cullyrammer Rd, Kilrea. monopole mast & radio receiver (for improved internet connection speeds) LA01/2018/0327/RM 12 Altikeeragh Lane, Replacement two-storey Castlerock, Coleraine. dwelling & garage. LA01/2018/0331/F Adjacent to No.15 Tirkeeran Dwelling & garage Rd, Garvagh. (C/2012/0109/RM) LA01/2018/0333/F 53 Ballywoodock Rd, Ground floor rear extension. Castlerock. LA01/2018/0335/RM 150m N of 50 Lisnagrot Rd, Two storey dwelling & garage Kilrea. on a Farm. Initial Adv BENBRADAGH LA01/2018/0329/F 41 Curragh Rd, Dungiven. New community walkway, fencing, spectator terrace area, landscaping & installation of 0.8m high bollard lighting colums. -

Co. Londonderry – Historical Background Paper the Plantation

Co. Londonderry – Historical Background Paper The Plantation of Ulster and the creation of the county of Londonderry On the 28th January 1610 articles of agreement were signed between the City of London and James I, king of England and Scotland, for the colonisation of an area in the province of Ulster which was to become the county of Londonderry. This agreement modified the original plan for the Plantation of Ulster which had been drawn up in 1609. The area now to be allocated to the City of London included the then county of Coleraine,1 the barony of Loughinsholin in the then county of Tyrone, the existing town at Derry2 with adjacent land in county Donegal, and a portion of land on the county Antrim side of the Bann surrounding the existing town at Coleraine. The Londoners did not receive their formal grant from the Crown until 1613 when the new county was given the name Londonderry and the historic site at Derry was also renamed Londonderry – a name that is still causing controversy today.3 The baronies within the new county were: 1. Tirkeeran, an area to the east of the Foyle river which included the Faughan valley. 2. Keenaght, an area which included the valley of the river Roe and the lowlands at its mouth along Lough Foyle, including Magilligan. 3. Coleraine, an area which included the western side of the lower Bann valley as far west as Dunboe and Ringsend and stretching southwards from the north coast through Macosquin, Aghadowey, and Garvagh to near Kilrea. 4. Loughinsholin, formerly an area in county Tyrone, situated between the Sperrin mountains in the west and the river Bann and Lough Neagh on the east, and stretching southwards from around Kilrea through Maghera, Magherafelt and Moneymore to the river Ballinderry. -

GAA Competition Report

H&A Mechanical Services ACFL Division 1 Round 1 - 31-03-2018 (Sat) Round 7 - 06-05-2018 (Sun) Round 13 - 12-08-2018 (Sun) Lavey v Dungiven Dungiven v Ballinascreen Coleraine v Ballinascreen Round 1 - 04-04-2018 (Wed) Ballinderry v Loup Bellaghy v Magherafelt Newbridge v Kilrea Newbridge v Greenlough Swatragh v Dungiven Coleraine v Claudy Bellaghy v Lavey Newbridge v Ballinderry Glen v Slaughtneil Slaughtneil v Claudy Slaughtneil v Lavey Magherafelt v Ballinascreen Coleraine v Kilrea Glen v Glenullin Ballinderry v Swatragh Glenullin v Magherafelt Greenlough v Claudy Bellaghy v Loup Glen v Swatragh (late evening) Loup v Kilrea Glenullin v Greenlough Round 8 - 15-07-2018 (Sun) Round 14 - 18-08-2018 (Sat) Round 2 - 08-04-2018 (Sun) Dungiven v Slaughtneil Kilrea v Swatragh Swatragh v Glenullin Glenullin v Newbridge*tbc Glenullin v Ballinderry Ballinascreen v Newbridge Lavey v Ballinascreen Magherafelt v Lavey Claudy v Lavey Ballinderry v Kilrea Newbridge v Coleraine Loup v Magherafelt Magherafelt v Claudy Dungiven v Glen Kilrea v Glen Swatragh v Bellaghy Slaughtneil v Ballinascreen Slaughtneil v Ballinderry Greenlough v Loup Claudy v Loup Greenlough v Coleraine Glen v Coleraine Bellaghy v Greenlough Round 2 - 09-04-2018 (Mon) Dungiven v Bellaghy Round 9 - 22-07-2018 (Sun) Round 15 – 24-08-2018 (Fri) Slaughtneil v Glenullin Coleraine v Glenullin Round 3 - 13-04-2018 (Fri) Bellaghy v Glen Lavey v Newbridge Newbridge v Claudy Newbridge v Magherafelt Kilrea v Claudy Round 3 - 15-04-2018 (Sun) Ballinascreen v Swatragh Ballinderry v Bellaghy Magherafelt -

Language Notes on Baronies of Ireland 1821-1891

Database of Irish Historical Statistics - Language Notes 1 Language Notes on Language (Barony) From the census of 1851 onwards information was sought on those who spoke Irish only and those bi-lingual. However the presentation of language data changes from one census to the next between 1851 and 1871 but thereafter remains the same (1871-1891). Spatial Unit Table Name Barony lang51_bar Barony lang61_bar Barony lang71_91_bar County lang01_11_cou Barony geog_id (spatial code book) County county_id (spatial code book) Notes on Baronies of Ireland 1821-1891 Baronies are sub-division of counties their administrative boundaries being fixed by the Act 6 Geo. IV., c 99. Their origins pre-date this act, they were used in the assessments of local taxation under the Grand Juries. Over time many were split into smaller units and a few were amalgamated. Townlands and parishes - smaller units - were detached from one barony and allocated to an adjoining one at vaious intervals. This the size of many baronines changed, albiet not substantially. Furthermore, reclamation of sea and loughs expanded the land mass of Ireland, consequently between 1851 and 1861 Ireland increased its size by 9,433 acres. The census Commissioners used Barony units for organising the census data from 1821 to 1891. These notes are to guide the user through these changes. From the census of 1871 to 1891 the number of subjects enumerated at this level decreased In addition, city and large town data are also included in many of the barony tables. These are : The list of cities and towns is a follows: Dublin City Kilkenny City Drogheda Town* Cork City Limerick City Waterford City Database of Irish Historical Statistics - Language Notes 2 Belfast Town/City (Co. -

1663 Hearth Money Rolls

Hearth Money Rolls [1663] for Co. Londonderry [T307] [Sorted by Surname, Barony, Parish and Townland] Record Surname Surname as spelt in Forename Barony Parish Townland Planter Irish No. [Standardised] Hearth Money Rolls 2237 [?] [?] John Coleraine Desertoghill Bellury [Balleway] 24 Acheson Atchison Patrick N. W. Liberties of L'Derry City of Londonderry Shipquay Street [Silver Street] 1995 Ackey Ackey Willm Loughinsholin Ballyscullion Not specified * 1517 Adams Adams Widow Coleraine Dunboe Not specified * 2674 Adams Adamms Robert Loughinsholin Maghera Largantogher [Leamontaer] * 1429 Adams Adams John N. E. Liberties of Coleraine Ballyaghran Kiltinny [Killenny] 1355 Adams Adams John N. E. Liberties of Coleraine Coleraine The Town & Parish of Coleraine 1249 Adams Adams Mr Willm N. E. Liberties of Coleraine Coleraine The Town & Parish of Coleraine 1225 Adams Adams Richard N. E. Liberties of Coleraine Coleraine The Town & Parish of Coleraine 1293 Adams Adams Willm Sen. N. E. Liberties of Coleraine Coleraine The Town & Parish of Coleraine 382 Adams Adam David Tirkeeran Clondermot Unidentified [Ballinetwady] * 2547 Adams Adams John Loughinsholin Tamlaght O'Crilly Tyanee [Tionee] * 2375 Adamson Adamson John Loughinsholin Ballinderry Ballydonnell * 2096 Adrain o'Dreane Hugh Loughinsholin Ballynascreen Gortnaskey [Gortnarkie] * 1467 Aiken Akine Mungo Coleraine Killowen Not specified * 784 Aiken Akinn William Keenaght Drumachose Limavady Town [Newtowne] * 712 Aiken Akine John Keenaght Tamlaght Finlagan Broglasco [Brugluzart] * 708 Aiken Akine Cowan -

RAILWAYS of BINEVENAGH AREA of OUTSTANDING NATURAL BEAUTY Varren

RAILWAYS OF BINEVENAGH AREA OF OUTSTANDING NATURAL BEAUTY Binevenagh Map.pdf 1 20/03/2018 10:51 Greencastle Portrush Republic of Magilligan North Coast Sea Causeway Ireland Point ATLANTIC Kayak Trail Coastal Route Martello Tower OCEAN Portstewart Derry/Londonderry Dhu Varren Moville Wild Atlantic Way Magilligan Mussenden Malin Head Prison Benone The Temple Point Road Beach Ark Downhill Portstewart Strand Castlerock Strand Ulster LOUGH Benone Visitor University FOYLE Centre University Foyle A2 Lower Canoe Trail Bann Magilligan Gortmore Field Centre A2 Seacoast Road Viewpoint Articlave A2 Quilly Road C Ulster A2 M Gliding Club Coleraine Y Altikeeragh Bellarena Bog CM Sconce Road Bishops Road MY Grange Park CY Forest Roe St. Aidan’s Binevenagh Giant’s Mountsandel CMY Estuary Church Lake Sconce K BINEVENAGH Swanns 385 M Ballyhanna Bridge Forest Key: Land over 200m North Sperrins Way River Roe A37 Land over 300m Railway Ballymacran l Road Woodland Railway Station Bank Windyhil Beach Ferry Crossing Seacoast Road Springwell Mudflat Parking Broighter Causeway Forest Cliff Toilets Ballykelly Gold Coastal Causeway Information Bank Economusee Route Coastal Route KEADY Viewpoint MOUNTAIN Alternative 337M Cam Scenic Route Monument Rough A37 Broad Road Forest Derry/Londonderry Walking/Cycle AONB Boundary Fort A2 Limavady Route Food Ballykelly A2 Ballykelly Road Tourism NI Tourism special biodiversity. special biodiversity. AONB’s andconservethe protect helpto Such designations Interest. Areas ofSpecial Scientific and of Conservation Areas Special including isreflectedindesignations habitats The importance ofthese andfauna. of flora support arange which specialhabitats landscapeishometo The Binevenagh defence heritage. rich exemplifyingthearea’s Magilligan, at Tower Martello asisthe AONB, withinthe isalsolocated Estate Downhill Temple and Mussenden The famous inthedistance. -

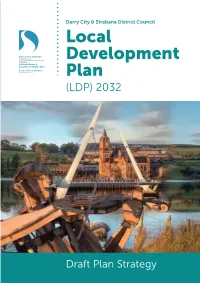

Local Development Plan (LDP) 2032 (LDP) 2032 - Draft Plan Strategy Plan Strategy (LDP) 2032 - Draft

Derry City & Strabane District Council Local Development Plan (LDP) 2032 (LDP) 2032 - Draft Plan Strategy Plan Strategy (LDP) 2032 - Draft Derry City and Strabane District Council 98 Strand Road 47 Derry Rd Derry Strabane BT48 7NN Tyrone, BT82 8DY Tel: (028) 71 253 253 E: [email protected] Website: www.derrystrabane.com/ldp Local Development Plan Find us on Facebook derrycityandstrabanedistrictcouncil Twitter @dcsdcouncil Draft Plan Strategy Consultation Arrangements Consultation Arrangements This LDP draft Plan Strategy (dPS) is a consultation document, to which representations can be made during a formal consultation period from Monday 2nd December 2019 to Monday 27th January 2020. Representations received after this date will not be considered. This dPS document is available, together with the associated documents, at http://www. derrystrabane.com/Subsites/LDP/Local-Development-Plan These documents are also available to view, during normal opening hours, at: • Council Offices, 98 Strand Road, Derry, BT48 7NN • Council Offices, 47 Derry Road, Strabane, BT82 8DY • Public Libraries and Council Leisure Centres throughout the District. Public Meetings and Workshops will be held throughout the District during December 2019 / January 2020; see the Council’s website and local press advertisements for details. This LDP draft Plan Strategy is considered by the Council to be ‘sound’; if you have any comments or objections to make, it is necessary to demonstrate why you consider that the Plan is not ‘sound’ and / or why you consider your proposal to be ‘sound’. Comments, or representations made in writing, will be considered at an Independent Examination (IE) conducted by the Planning Appeals Commission (PAC) or other independent body that will be appointed by the Department for Infrastructure (DfI). -

The Londonderry Plantation from 1641 Until the Disengagement at the End of the Nineteenth Century Transcript

The Londonderry Plantation from 1641 until the Disengagement at the end of the Nineteenth Century Transcript Date: Wednesday, 23 October 2013 - 6:00PM Location: Barnard's Inn Hall 23 October 2013 The Londonderry Plantation from 1641 until the Disengagement at the end of the Nineteenth Century Professor James Stevens Curl It is an unfortunate fact that Irish history tends to be bedevilled by cherished beliefs rather than coolly informed by dispassionate examinations of facts: added to this distressing state of affairs, commentators on the eastern side of the Irish Sea seem to lose their senses when dealing with any aspects of Ireland whatsoever, or (and I do not hazard a view as to which is worse) ignore the place entirely, expunging it from the record. For example, if we take the Londonderry Plantation, misrepresentation and confusion are beyond belief: some pretend it never happened; some hold fast to absurd notions about it, even denouncing it as the source of all the so-called ‘Troubles’ ever since; some, secure in their fortresses of invincible ignorance, have never heard about it at all; and very few, from any background, seem able to grasp the truth that nothing occurs in a vacuum, for events in Ireland were always part of a much wider series of historical upheavals, almost invariably closely connected with uproar on the European Continent, especially power-struggles, and in the seventeenth century context, this should be glaringly obvious, even to the most myopic. Yet Anglocentric historians, even in recent times, completely miss the importance of the Londonderry Plantation in shaping events of the 1640s and 1650s in British history, or take the path, not of the myopic, but of the blind. -

![County Londonderry - Townlands: Landed Estates [Sorted by Townland]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4927/county-londonderry-townlands-landed-estates-sorted-by-townland-1994927.webp)

County Londonderry - Townlands: Landed Estates [Sorted by Townland]

County Londonderry - Townlands: Landed Estates [Sorted by Townland] Recor O.S. Sheet Townland Parish Barony Poor Law Union Estates [Immediate Lessors in Seventeenth Century Freeholds, etc. d No. No. Griffith's, 1859] 1 11, 18 Aghadowey Aghadowey Coleraine Coleraine William S. Alexander Churchland 2 42 Aghagaskin Magherafelt Loughinsholin Magherafelt Salters Salters 3 17 Aghansillagh Balteagh Keenaght Limavady Marquis of Waterford Haberdashers Native Freehold 4 22, 23, 28, Alla Lower Cumber Upper Tirkeeran Londonderry Rev. Thomas Lindsay Churchland 29 5 22, 28 Alla Upper Cumber Upper Tirkeeran Londonderry Rev. Thomas Lindsay Churchland 6 28, 29 Altaghoney Cumber Upper Tirkeeran Londonderry Trustees, James Ogilby Skinners 7 17, 18 Altduff Errigal Coleraine Coleraine Lady Garvagh Ironmongers Crown Freehold 8 6 Altibrian Formoyle / Dunboe Coleraine Coleraine John Alexander Clothworkers Crown Freehold 9 6 Altikeeragh Dunboe Coleraine Coleraine Clothworkers Clothworkers 10 29, 30 Altinure Lower Learmount / Banagher Tirkeeran Londonderry Thomas McCausland Skinners Crown Freehold 11 29, 30 Altinure Upper Learmount / Banagher Tirkeeran Londonderry John B. Beresford Fishmongers Crown Freehold 12 20 Altnagelvin Clondermot Tirkeeran Londonderry John Adams Goldsmiths 13 41 Annagh and Desertmartin Loughinsholin Magherafelt Reps. Rev. Robert Torrens Churchland Moneysterlin 14 42 Annaghmore Magherafelt Loughinsholin Magherafelt Robert P. Dawson Phillips Freehold 15 48 Annahavil Arboe Loughinsholin Magherafelt Drapers Drapers 16 48 Annahavil Derryloran Loughinsholin Magherafelt Drapers Drapers 17 49 Ardagh Ballinderry Loughinsholin Magherafelt John J. O'F. Carmichael Salters Native Freehold 18 10, 16, 17 Ardgarvan Drumachose Keenaght Limavady Marcus McCausland Churchland 19 22 Ardground Cumber Lower Tirkeeran Londonderry Trustees, James Ogilby Skinners W. Macafee 1 28/10/2013 County Londonderry - Townlands: Landed Estates [Sorted by Townland] Recor O.S. -

The Full Details of Following Planning Applications Including Plans, Maps

Cloonavin, 66 Portstewart Road, Coleraine, BT52 1EY Tel +44 (0) 28 7034 7034 Web www.causewaycoastandglens.gov.uk Planning Applications The full details of following planning applications including plans, maps and drawings are available to view on the NI Planning Portal www.planningni.gov.uk or at the Council Planning Office or by contacting 0300 200 7830. Written comments should be submitted within the next 14 days. Please quote the application number in any correspondence and note that all representations made, including objections, will be posted on the NI Planning Portal. The schedule of Planning Applications being presented to the Council on 22nd February 2017 is also available on the NI Planning Portal www.planningni.gov.uk. David Jackson Chief Executive APPLICATION LOCATION BRIEF DESCRIPTION Initial Adv BALLYMONEY LA01/2017/0096/F 30 Victoria St, Ballymoney. Four bi-directional wall lights & two up-lights to front elevation. LA01/2017/0099/F 6 Mounthill Court, Cloughmills. Ground floor side & rear extension. LA01/2017/0103/F 16 Finvoy Rd, Ballymoney. Two storey internal office accommodation Re-Adv LA01/2016/1115/F 38 Killagan Rd, Glarryford, Private Collectors Car Store Ballymena. & extension to existing site curtilage. Initial Adv BANN LA01/2017/0090/F 39 Castleroe Rd, Coleraine. 4 no semi-detached dwellings. LA01/2017/0100/F 16 Cairnhill, Coleraine. Single storey side extension. Initial Adv BENBRADAGH LA01/2017/0083/O 253 Altinure Rd, Claudy. Replacement dwelling. LA01/2017/0085/O 251 Altinure Rd, Claudy. Replacement dwelling. LA01/2017/0093/O 252m E of 89 New Line Rd, Replacement dwelling & Limavady. garage. LA01/2017/0102/F Lands approx. -

The Project of Plantation”

2b:creative 028 9266 9888 ‘The Project North East PEACE III Partnership of Plantation’ A project supported by the PEACE III Programme managed for the Special EU Programmes Body 17th Century changes in North East Ulster by the North East PEACE III Partnership. ISBN-978-0-9552286-8-1 People & Places Cultural Fusions “The Project of Plantation” Cultural Fusions “The Project of Plantation” has been delivered by Causeway Museum Service and Mid-Antrim Museums Service across the local councils of Coleraine, Ballymena, Ballymoney, Larne, Limavady and Moyle. It is supported by the PEACE III Programme through funding from the Special EU Programmes Body administered by the North East PEACE III Partnership. The project supports the Decade of Anniversaries initiative and the 400th anniversaries of the granting of Royal Town Charters to Coleraine and Limavady, as part of the peace building process within our communities. Background images The project encourages a re-interpretation of the 17th century period based on new evidence and thinking . It aims to enable dialogue and discussion around the John Speed map of Ireland 1605-1610 - Page 2, 4, 5, 26 Petty’s Down Survey Barony Maps, 1656-1658 commemoration of key historical events to support peace and reconciliation building though a range of resources including: Courtesy of Cardinal Tomas OFiaich Library and Archive Toome - 29, 31, 32 Glenarm - Page 28 An extensive tour exploring the histories revealed by our heritage landscapes providing information to allow site visits to be selected to suit learning needs Map of Carrickfergus, by Thomas Philips, 1685 - Page 3 Kilconway - Page 37 Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland Glenarm - Page 36, 40, 44 A major object based exhibition touring to venues across the North East PEACE III cluster area and beyond Carey - Page 41 Early 17th century map - Page 6, 7 Courtesy of Public Records Office Northern Ireland New learning resources for community groups and to support the Northern Ireland curriculum.