Review Recognition of Specific DNA Sequences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transcriptional Regulation by Extracellular Signals 209

Cell, Vol. 80, 199-211, January 27, 1995, Copyright © 1995 by Cell Press Transcriptional Regulation Review by Extracellular Signals: Mechanisms and Specificity Caroline S. Hill and Richard Treisman Nuclear Translocation Transcription Laboratory In principle, regulated nuclear localization of transcription Imperial Cancer Research Fund factors can involve regulated activity of either nuclear lo- Lincoln's Inn Fields calization signals (NLSs) or cytoplasmic retention signals, London WC2A 3PX although no well-characterized case of the latter has yet England been reported. N LS activity, which is generally dependent on short regions of basic amino acids, can be regulated either by masking mechanisms or by phosphorylations Changes in cell behavior induced by extracellular signal- within the NLS itself (Hunter and Karin, 1992). For exam- ing molecules such as growth factors and cytokines re- ple, association with an inhibitory subunit masks the NLS quire execution of a complex program of transcriptional of NF-KB and its relatives (Figure 1; for review see Beg events. While the route followed by the intracellular signal and Baldwin, 1993), while an intramolecular mechanism from the cell membrane to its transcription factor targets may mask NLS activity in the heat shock regulatory factor can be traced in an increasing number of cases, how the HSF2 (Sheldon and Kingston, 1993). When transcription specificity of the transcriptional response of the cell to factor localization is dependent on regulated NLS activity, different stimuli is determined is much less clear. How- linkage to a constitutively acting NLS may be sufficient to ever, it is possible to understand at least in principle how render nuclear localization independent of signaling (Beg different stimuli can activate the same signal pathway yet et al., 1992). -

NF-Κb Modifies the Mammalian Circadian Clock Through Interaction with the Core Clock Protein BMAL1

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.09.06.285254; this version posted September 6, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. NF-κB modifies the mammalian circadian clock through interaction with the core clock protein BMAL1 Yang Shen1, Wei Wang2, Mehari Endale1, Lauren J. Francey3, Rachel L. Harold4, David W. Hammers5, Zhiguang Huo6, Carrie L. Partch4, John B. Hogenesch3, Zhao-Hui Wu2, and Andrew C. Liu1* 1Department of Physiology and Functional Genomics, University of Florida College of Medicine; 2Department of Radiation Oncology and Center for Cancer Research, University of Tennessee Health Science Center; 3Divisions of Human Genetics and Immunobiology, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center; 4Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of California Santa Cruz; 5Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics, University of Florida College of Medicine; 6Department of Biostatistics, College of Public Health & Health Professions, University of Florida College of Medicine Running title: NF-κB modifies circadian clock * Correspondence: Andrew C. Liu, [email protected] Keywords: Circadian clock, inflammation, NF-κB, suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), BMAL1 Abbreviations: NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa B; SCN, suprachiasmatic nucleus; IKK, IκB kinase; IκBα, inhibitor of NF-κB; Luc, luciferase; RHD, Rel homology domain; CRD, C-terminal oscillation regulatory domain, TAD, transactivation domain 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.09.06.285254; this version posted September 6, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. -

Susceptibility of Heterozygous and Nullizygous P53 Knockout Mice to Chemical Carcinogens: Tissue Dependence and Role of P53 Gene Mutations

J Toxicol Pathol 2005; 18: 121–134 Review Susceptibility of Heterozygous and Nullizygous p53 Knockout Mice to Chemical Carcinogens: Tissue Dependence and Role of p53 Gene Mutations Tetsuya Tsukamoto1, Akihiro Hirata1, and Masae Tatematsu1 1Division of Oncological Pathology, Aichi Cancer Center Research Institute, 1–1 Kanokoden, Chikusa-ku, Nagoya 464–8681, Japan Abstract: Mutations of the p53 tumor suppressor gene constitute one of the most frequent molecular changes in a wide variety of human cancers and mice deficient in p53 have recently attracted attention for their potential to identify chemical genotoxins. In this article, we review the data on the susceptibility of p53 nullizygote (–/–), heterozygote (+/ –), and wild type (+/+) mice to various carcinogens. Induction of esophageal and tongue squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) by methyl-n-amylnitrosamine was shown to be increased in p53 (+/–) mice, in addition to the high sensitivity shown by p53 (–/–) littermates. N,N-dibutylnitrosamine (DBN) treatment also caused more tumor development in p53 (+/–) than wild-type mice, as with N-butyl-N-(4-hydroxybutyl)nitrosamine (BBN) in the urinary bladder. In addition, p53 (+/–) heterozygotes proved more sensitive than wild type littermates to the induction of stromal cell tumors like hemangiomas/hemangiosarcomas by N-bis(2-hydroxypropyl)nitrosamine (BHP) or lymphomas and fibrosarcomas with other carcinogens. Analysis of exons 5–8 of the p53 gene demonstrated mutations in approximately one half of the lesions. With N-methyl-N-nitrosourea, preneoplastic lesions of the stomach, pepsinogen altered pyloric glands (PAPG), and a gastric adenocarcinoma, were found after only 15 weeks in p53 (–/–) mice, although there was no significant difference in the incidence of gastric tumors between p53 (+/+) and (+/–) mice in the longer-term. -

Transcriptional Control of Tissue-Resident Memory T Cell Generation

Transcriptional control of tissue-resident memory T cell generation Filip Cvetkovski Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2019 © 2019 Filip Cvetkovski All rights reserved ABSTRACT Transcriptional control of tissue-resident memory T cell generation Filip Cvetkovski Tissue-resident memory T cells (TRM) are a non-circulating subset of memory that are maintained at sites of pathogen entry and mediate optimal protection against reinfection. Lung TRM can be generated in response to respiratory infection or vaccination, however, the molecular pathways involved in CD4+TRM establishment have not been defined. Here, we performed transcriptional profiling of influenza-specific lung CD4+TRM following influenza infection to identify pathways implicated in CD4+TRM generation and homeostasis. Lung CD4+TRM displayed a unique transcriptional profile distinct from spleen memory, including up-regulation of a gene network induced by the transcription factor IRF4, a known regulator of effector T cell differentiation. In addition, the gene expression profile of lung CD4+TRM was enriched in gene sets previously described in tissue-resident regulatory T cells. Up-regulation of immunomodulatory molecules such as CTLA-4, PD-1, and ICOS, suggested a potential regulatory role for CD4+TRM in tissues. Using loss-of-function genetic experiments in mice, we demonstrate that IRF4 is required for the generation of lung-localized pathogen-specific effector CD4+T cells during acute influenza infection. Influenza-specific IRF4−/− T cells failed to fully express CD44, and maintained high levels of CD62L compared to wild type, suggesting a defect in complete differentiation into lung-tropic effector T cells. -

Structure and Evolution of Four POU Domain Genes Expressed in Mouse Brain (POU Bnain-/POU Brain-2/POU Brain4/POU Scip/Homeobox) YOSHINOBU HARA*, ALESSANDRA C

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 89, pp. 3280-3284, April 1992 Neurobiology Structure and evolution of four POU domain genes expressed in mouse brain (POU Bnain-/POU Brain-2/POU Brain4/POU Scip/homeobox) YOSHINOBU HARA*, ALESSANDRA C. ROVESCALLI, YONGSOK KIM, AND MARSHALL NIRENBERG Laboratory of Biochemical Genetics, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892 Contributed by Marshall Nirenberg, January 6, 1992 ABSTRACT Four mouse POU domain genomic DNA acid sequences of the proteins are related to one another and clones-Brain-i, Brain-2, Brain-4, and Scip-and Bran-2 suggests that the genes originated by duplication of an cDNA, which are expressed in adult brain, were cloned and the ancestral class III POU domain gene.t coding and noncoding regions ofthe genes were sequenced. The amino acid sequences of the four PoU domains are highly conserved; sequences in other regions of the proteins also are MATERIALS AND METHODS conserved but to a lesser extent. The absence of introns from DNA Coming and Sequencing. Our objective was to clone the coding regions of the four POU domain genes and the POU domain genes expressed in mouse brain. Mixtures of similarity of amino acid sequences of the corresponding pro- oligodeoxynucleotides that correspond to highly conserved teins suggest that the coding region of the ancestral class HI amino acid sequences in POU domains were used as primers POU domain gene lacked introns and therefore may have for amplification ofadult mouse brain POU domain cDNA by originated by reverse transcription of a molecule of POU PCR, and the amplified DNA fragments were cloned. -

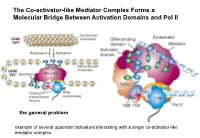

The Co-Activator-Like Mediator Complex Forms a Molecular Bridge Between Activation Domains and Pol II

The Co-activator-like Mediator Complex Forms a Molecular Bridge Between Activation Domains and Pol II Co-activator the general problem example of several upstream activators interacting with a single co-activator-like mediator complex Transcription Regulation And Gene Expression in Eukaryotes FS 2016 Graduate Course G2 P. Matthias and RG Clerc Pharmazentrum Hörsaal 2 16h15-18h00 REGULATORY MECHANISMS OF TRANSCRIPTION FACTOR FUNCTION •Protein synthesized •Protein phosphorylated •Ligand binding •Release inhibitor •Change partner, etc RG Clerc April 6. 2016 Transcription factors as final effectors of the cellular signaling cascade Regulatory Mechanisms of Transcription Factor Function Genes X. Lewin B. editor Regulatory Mechanisms of Transcription Factor Function CREB FOXO NFAT Genes X. Lewin B. editor Body plan is constructed through interactions of the developmentally regulated homeotic gene expression anterior early expression posterior late expression high RA response low RA response hindbrain trunk Alexander T and Krumlauf R. Ann.Rev.Cell.Dev.Biol: 25_431 (2009) Hoxb transcription factors mRNA distribution along the AP axis A staggered expression of the anterior border within somites is a property of the physical ordering along the chromosome: the colinearity Alexander T and Krumlauf R. Ann.Rev.Cell.Dev.Biol: 25_431 (2009) Transcription control of the Hox genes: insight into colinear activation P A p p p p a p a p a a a a Tarchini B and Duboule D. Dev.Cell 10_93 (2006) correlation between linear arrangement along the chromosome and spatial -

The C-Rel Transcription Factor and B-Cell Proliferation: a Deal with the Devil

Oncogene (2004) 23, 2275–2286 & 2004 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0950-9232/04 $25.00 www.nature.com/onc REVIEW The c-Rel transcription factor and B-cell proliferation: a deal with the devil Thomas D Gilmore*,1, Demetrios Kalaitzidis1, Mei-Chih Liang1 and Daniel T Starczynowski1 1Department of Biology, Boston University, 5 Cummington Street, Boston, MA 02215, USA Activation of the Rel/NF-jB signal transduction pathway called the Rel homology domain, which has sequences has been associated with a varietyof animal and human required for DNA binding, dimerization, nuclear malignancies. However, among the Rel/NF-jB family localization, and inhibitor (IkB) binding. Sequences members, onlyc-Rel has been consistentlyshown to be C-terminal to the Rel homology domain in c-Rel, RelA, able to malignantlytransform cells in culture. In addition, and RelB contain transcriptional activation domains, c-rel has been activated bya retroviral promoter insertion and therefore dimers that contain these Rel/NF-kB in an avian B-cell lymphoma, and amplifications of REL members usually increase transcription of target genes. (human c-rel) are frequentlyseen in Hodgkin’s lympho- Although the Rel homology domain sequences of c-Rel mas and diffuse large B-cell lymphomas, and in some proteins across species are highly conserved, their follicular and mediastinal B-cell lymphomas. Phenotypic C-terminal transactivation domains are not. For exam- analysis of c-rel knockout mice demonstrates that c-Rel ple, the Rel homology domains of chicken and human has a normal role in B-cell proliferation and survival; c-Rel are approximately 85% identical, whereas their moreover, c-Rel nuclear activityis required for B-cell C-terminal transactivation domains are only about 10% development. -

The Role of Ubiquitination in NF-Κb Signaling During Virus Infection

viruses Review The Role of Ubiquitination in NF-κB Signaling during Virus Infection Kun Song and Shitao Li * Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA 70112, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) family are the master transcription factors that control cell proliferation, apoptosis, the expression of interferons and proinflammatory factors, and viral infection. During viral infection, host innate immune system senses viral products, such as viral nucleic acids, to activate innate defense pathways, including the NF-κB signaling axis, thereby inhibiting viral infection. In these NF-κB signaling pathways, diverse types of ubiquitination have been shown to participate in different steps of the signal cascades. Recent advances find that viruses also modulate the ubiquitination in NF-κB signaling pathways to activate viral gene expression or inhibit host NF-κB activation and inflammation, thereby facilitating viral infection. Understanding the role of ubiquitination in NF-κB signaling during viral infection will advance our knowledge of regulatory mechanisms of NF-κB signaling and pave the avenue for potential antiviral therapeutics. Thus, here we systematically review the ubiquitination in NF-κB signaling, delineate how viruses modulate the NF-κB signaling via ubiquitination and discuss the potential future directions. Keywords: NF-κB; polyubiquitination; linear ubiquitination; inflammation; host defense; viral infection Citation: Song, K.; Li, S. The Role of 1. Introduction Ubiquitination in NF-κB Signaling The nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) is a small family of five transcription factors, including during Virus Infection. Viruses 2021, RelA (also known as p65), RelB, c-Rel, p50 and p52 [1]. -

BRN2 Is a Transcriptional Repressor of CDH13 (T-Cadherin)

Laboratory Investigation (2012) 92, 1788–1800 & 2012 USCAP, Inc All rights reserved 0023-6837/12 $32.00 BRN2 is a transcriptional repressor of CDH13 (T-cadherin) in melanoma cells Lisa Ellmann1, Manjunath B Joshi2,3, Therese J Resink2, Anja K Bosserhoff1 and Silke Kuphal1 T-cadherin (cadherin 13, H-cadherin, gene name CDH13) has been proposed to act as a tumor-suppressor gene as its expression is significantly diminished in several types of carcinomas, including melanomas. Allelic loss and promoter hypermethylation have been proposed as mechanisms for silencing of CDH13. However, they do not account for loss of T-cadherin expression in all carcinomas, and other genetic or epigenetic alterations can be presumed. The present study investigated transcriptional regulation of CDH13 in melanoma. Bioinformatical analysis pointed to the presence of known BRN2 (also known as POU3F2 and N-Oct-3)-binding motifs in the CDH13 promoter sequence. We found an inverse correlation between BRN2 and T-cadherin protein and transcript expression. Reporter gene analysis and electrophoretic mobility shift assays in melanoma cells demonstrated that CDH13 is a direct target of BRN2 and that BRN2 is a functional transcriptional repressor of CDH13 promoter activity. The regulatory binding element of BRN2 was located À 219 bp of the CDH13 promoter proximal to the start codon and was identified as 50-CATGCAAAA-30. Ectopic expression of BRN2 in BRN2-negative/T-cadherin-positive melanoma cells resulted in suppression of CDH13 promoter activity, whereas BRN2 knockdown in BRN2-positive/T-cadherin-negative melanoma cells resulted in re-expression of T-cadherin transcripts and protein. -

POU Domain Family Values: Flexibility, Partnerships, and Developmental Codes

Downloaded from genesdev.cshlp.org on October 1, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press REVIEW POU domain family values: flexibility, partnerships, and developmental codes Aimee K. Ryan and Michael G. Rosenfeld 1 Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Department and School of Medicine, University of California at San Diego, La Jolla, Califiornia 92093-0648 USA Transcription factors serve critical roles in the progres- primary focus of this review. Crystallization of the Oct-1 sive development of general body plan, organ commit- and Pit-1 POU domains on DNA and in vitro studies ment, and finally, specific cell types. It has been the hope examining the specificity of POU domain cofactor inter- of most developmental biologists that comparison of the actions suggest that the flexibility with which the POU biological roles of a series of individual members within domain recognizes DNA-binding sites is a critical com- a family will permit at least some predictive generaliza- ponent of its ability to regulate gene expression. The tions regarding the developmental events that are likely implications of these data with respect to the mecha- to be regulated by a particular class of transcription fac- nisms utilized by the POU domain family of transcrip- tors. Here, we present an overview of the developmental tion factors to control developmental events will also be functions of the family of transcription factors charac- discussed. terized by the POU DNA-binding motif afforded by re- cent in vivo studies. Conformation of the POU domain on DNA The POU domain family of transcription factors was defined following the observation that the products of High-affinity site-specific DNA binding by POU domain three mammalian genes, Pit-l, Oct-l, and Oct-2 and the transcription factors requires both the POU-specific do- protein encoded by the Caenorhabditis elegans gene main and the POU homeodomain (Sturm and Herr 1988; unc-86 shared a region of homology, known as the POU Ingraham et al. -

Significance of Wilms' Tumor Gene 1 As a Biomarker in Acute Leukemia and Solid Tumors

UMEÅ UNIVERSITY MEDICAL DISSERTATIONS New Series No. 1799 ISSN 0346-6612 ISBN 978-91-7601-458-5 Significance of Wilms’ Tumor Gene 1 as a Biomarker in Acute Leukemia and Solid Tumors Charlotta Andersson Department of Medical Biosciences, Clinical Chemistry and Pathology Umeå University, Sweden Umeå 2016 Copyright © 2016 Charlotta Andersson ISBN: 978-91-7601-458-5 ISSN: 0346-6612 Printed by: Print & Media Umeå, Sweden, 2016 In memory of Aihong Li Table of Contents Table of Contents i Abstract iii Abbreviations iv List of Papers v Introduction 1 WT1 structure 1 WT1 target genes 3 WT1 protein partners 5 WT1 in normal and abnormal development 5 Hematopoiesis and WT1 7 WT1 as a tumor suppressor gene 7 WT1 as an oncogene or a chameleon gene 7 Acute leukemia (AL) and WT1 in AL 8 Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) and WT1 in RCC 13 Ovarian carcinoma (OC) and WT1 in OC 15 Aims of the Thesis 20 Materials and Methods 21 Patients and tissue samples (Papers I-IV) 21 Classification and risk group stratification in AL (Papers I and IV) 22 ccRCC grade and stage (Paper II) 22 OC classification, grade and stage (Paper III) 22 Genomic DNA preparation, RNA extraction and cDNA preparation (Papers I, II and IV) 23 Quantitative assessment of WT1 transcript expression with real-time quantitative PCR (RQ-PCR) (Papers I and II) 23 Sequencing analysis of the WT1 gene (Papers II and IV) 24 Immunohistochemistry (IHC) (Paper III) 24 Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Paper III) 25 Statistical analysis 25 Results and Discussion 27 Paper I 27 Paper II 31 Paper III 35 Paper IV 38 Conclusions 42 Acknowledgments 44 References 47 i ii Abstract Wilms’ tumor gene 1 (WT1) is a zinc finger transcriptional regulator with crucial functions in embryonic development. -

And C-Terminal Domains of Relb Are Required for Full Transactivation

MOLECULAR AND CELLULAR BIOLOGY, Mar. 1993, p. 1572-1582 Vol. 13, No. 3 0270-7306/93/031572-11$02.00/0 Copyright © 1993, American Society for Microbiology Both N- and C-Terminal Domains of RelB Are Required for Full Transactivation: Role of the N-Terminal Leucine Zipper-Like Motif PAWEL DOBRZANSKI, ROLF-PETER RYSECK, AND RODRIGO BRAVO* Department ofMolecular Biology, Bristol-Myers Squibb Pharmaceutical Research Institute, P.O. Box 4000, Princeton, New Jersey 08543-4000 Received 18 September 1992/Returned for modification 11 November 1992/Accepted 12 December 1992 RelB, a member of the Rel family of transcription factors, can stimulate promoter activity in the presence of p50-NF-KB or p5OB/p49-NF-KB in mammalian cells. Transcriptional activation analysis reveals that the N and C termini of RelB are required for full transactivation in the presence of p50-NF-KB. RelB/p50-NF-KB hybrid molecules containing the Rel homology domain of p50-NF-KB and the N and C termini of RelB have high transcriptional activity compared with wild-type p50-NF-KB. The N and C termini of RelB cooperate in transactivation in cis or trans configuration. Alterations in the structure of the leucine zipper-like motif present in the N terminus of RelB significantly decrease the transcriptional capacity of RelB and of different RelB/p50-NF-KB hybrid molecules. Serum stimulation of quiescent fibroblasts induces the regulated by the inhibitory factor cactus (28). The different expression of more than 100 genes, including several proto- homodimers and heterodimers formed between the members oncogenes encoding for transcriptional factors belonging to of the Rel family regulate gene expression in vivo (20, 22, 42) the Jun, Fos, and Rel families (2, 11, 13, 24, 34-36, 38).