Duke University Dissertation Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

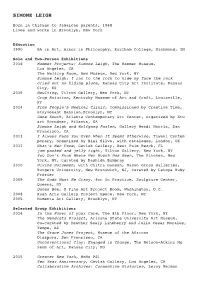

SIMONE LEIGH B. 1968, Chicago, IL Lives and Works in Brooklyn, NY

SIMONE LEIGH b. 1968, Chicago, IL Lives and works in Brooklyn, NY EDUCATION 1990 BA in Art and Philosophy, Earlham College, Richmond, IN SOLO AND TWO-PERSON EXHIBITIONS 2016 Psychic Friends Network with Simone Leigh, Tate Exchange, Tate Modern London, UK Hammer Projects: Simone Leigh, The Hammer Museum Los Angeles, CA The Waiting Room, New Museum, New York, NY Simone Leigh: I ran to the rock to hide my face the rock cried out no hiding place, H&R Block Artspace at the Kansas City Art Institute, Kansas City, MO 2015 Moulting, Tilton Gallery, New York, NY Crop Rotation, Kentucky Museum of Art and Craft, Louisville, KY 2014 Free People’s Medical Clinic, commissioned by Creative Time, Stuyvesant Mansion, Brooklyn, NY Gone South, Atlanta Contemporary Art Center, organized by Stuart Horodner Atlanta, GA Simone Leigh and Wolfgang Paalen, Gallery Wendi Norris, San Francisco, CA 2013 I Always Face You Even When It Seems Otherwise, Tiwani Contemporary, organized by Bisi Silva, London, England (catalogue) 2012 What's Her Face, Gavlak, Palm Beach, FL You Don’t Know Where Her Mouth Has Been, curated by Rashida Bumbray, The Kitchen, New York, NY jam packed and jelly tight, Jack Tilton Gallery, New York, NY 2009 The Gods Must Be Crazy, for In Practice, SculptureCenter, Queens, NY Queen Bee, G Fine Art Project Room, Washington, D.C. 2008 Scratching the Surface Vol 1, organized by Gabi Ngcobo and Mwenya Kabwe, L'appartement 22, Rabat, Morocco if you wan fo' lick old woman pot, you scratch him back (Jamaican proverb), Rush Arts Gallery Project Space, New -

Simone Leigh: the Waiting Room

SIMONE LEIGH THE WAITING ROOM JUNE 22 SEPT 18 For artist Simone Leigh, what happens within the duration and space of waiting is active, personal, political, and, in turn, an opportunity for reflection brimming with revolutionary potential. By way of introducing audiences to such a sense of lim- inal, yet urgent, possibility, the artist is apt to tell the disturbing story of Esmin Green. On June 18, 2008, the forty-nine-year-old woman was forcibly admitted to the psychiatric emergency depart- ment of Kings County Hospital Center, in Brooklyn, New York, due to “psychosis and agitation,” and subsequently waited for nearly twenty-four hours to receive treatment that never came. Instead, at 5:42 a.m. the following day, Green collapsed in her waiting room chair, falling to the floor—where she lay for more than an hour, unattended by employ- ees who nevertheless stood by and looked on as she died. Adding to this tragedy was the fact that those who presumed themselves Green’s caretakers sought to skew documentation of this event: Contrary to what was recorded from four different angles by the hospital’s video cameras, her medical records say that at 6 a.m. she stood up and went to the bathroom—when in truth she was already lying on the floor—and that at 6:20 a.m. she was “sitting quietly in the waiting room.” And so while Green—a Jamaican native who lived in Brownsville, and who, according to a neighbor, kept to herself except for her regular visits to church—was claimed to have died due to a “deep venous thrombosis of lower extremities due to physical inactivity,” she could best be said to have died from waiting. -

On the Art of Healing Simone Leigh’S the Waiting Room

tema On the Art of Healing Simone Leigh’s The Waiting Room Elke Krasny Elke Krasny, cultural theorist and curator. Professor at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna Her body’s and her mind’s health have been made both a risk and a responsi- bility. What do I mean by this paradoxical statement? And, who is she? And, who cares about her risks, her responsibilities, her health and hear healing? The following essay will engage with these questions as it centers on artist Simone Leigh’s work The Waiting Room which took place at the New Museum in New York in 2016. The analytical reflections presented here connect the description of the social and aesthetic strategies of The Waiting Room, a key example of health activism and black feminist practice in contemporary art making, to the broader context of the politics of health, the crisis of social reproduction under neolibe- ralism, and the gendered and racialized body. Simone Leigh’s chose The Waiting Room as a title for her work to refer to the emergency waiting room at Kings County Hospital in Brooklyn, where in 2008 a Jamaican immigrant to the United States, who had been involuntarily admit- ted to the hospital, died from neglect after she had waited for nearly twenty-four hours.1 “The patient, Esmin Green, died in the waiting room at the city-run psychiatric facility in 2008. A security video released by the New York Civil Liberties Union and other lawyers showed Ms. Green, 49, collapsing to the floor and lying there while workers ignored her. -

Aesthetics, Imagination, and Radical Reciprocity: an Interview with Girl

Simone Leigh, Chitra Ganesh, and Uri McMillan ALTERNATIVE STRUCTURES: AESTHETICS, IMAGINATION, AND RADICAL RECIPROCITY: AN INTERVIEW WITH GIRL n the spring of 2012, on a visit to New York City, I took the train up to the Upper West Side on an explicit mission to visit the Jack Tilton I Gallery. In a striking turn of fate, the gallery was running not one Simone Leigh. Photograph by Paul Mpagi Sepuya. Chitra Ganesh. Photograph by C. Ganesh. ASAP/Journal, Vol. 2.2 (2017): 241-252 © 2017 Johns Hopkins University Press. but two of my friends’ solo exhibitions simultaneously: CHITRA GANESH’s The For Leigh “and Ganesh, art Ghost Efect in Real Time and SIMONE and friendship are delicately LEIGH’s jam packed and jelly tight. intertwined and mutually Traversing elegant narrow mansions with transformative. pristine balustrades and faded facades in the upper 70s, I eventually entered a large ” space where I was immediately greeted by one of Leigh’s arresting sculptures: a sinuous and slender wood tree trunk reaching toward the ceiling, where it cradled one of Leigh’s large ceramic glazed cowrie shells covered in a brilliant appliqué of gold leaf. Upstairs, as I traversed Leigh’s sculptures—chandeliers of pendulous glass containers flled with salt; a row of six fgurines with headdresses made out of voluptuous confgurations of cobalt blue ceramic roses—I encountered Ganesh’s large-scale black-and- white charcoal drawings of scenes inspired by early cinema productions in India, Germany, and the United States. Ganesh’s drawings contained imagery culled from science fction, histories of Orientalism, and epic myth. -

Simone Leigh

SIMONE LEIGH Born in Chicago to Jamaican parents, 1968 Lives and works in Brooklyn, New York Education 1990 BA in Art, minor in Philosophy, Earlham College, Richmond, IN Solo and Two-Person Exhibitions 2016 Hammer Projects: Simone Leigh, The Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, CA The Waiting Room, New Museum, New York, NY Simone Leigh: I ran to the rock to hide my face the rock cried out no hiding place, Kansas City Art Institute, Kansas City, KS 2015 Moulting, Tilton Gallery, New York, NY Crop Rotation, Kentucky Museum of Art and Craft, Louisville, KY 2014 Free People’s Medical Clinic, commissioned by Creative Time, Stuyvesant Mansion,Brooklyn, NY Gone South, Atlanta Contemporary Art Center, organized by Stu art Horodner, Atlanta, GA Simone Leigh and Wolfgang Paalen, Gallery Wendi Norris, San Francisco, CA 2013 I Always Face You Even When It Seems Otherwise, Tiwani Contem porary, organized by Bisi Silva, with catalogue, London, UK 2012 What’s Her Face, Gavlak Gallery, West Palm Beach, FL jam packed and jelly tight, Tilton Gallery, New York, NY You Don’t Know Where Her Mouth Has Been, The Kitchen, New York, NY, curated by Rashida Bumbray 2010 Divine Horsemen, with Chitra Ganesh, Mason Gross Galleries, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, curated by Latoya Ruby Frazier 2009 The Gods Must Be Crazy, for In Practice, Sculpture Center, Queens, NY Queen Bee, G Fine Art Project Room, Washington, D.C. 2008 Rush Arts Gallery Project Space, New York, NY 2005 Momenta Art Gallery, Brooklyn, NY Selected Group Exhibitions 2016 In the Power of your Care, The -

New Museum Announces Free Public Event with Black Women Artists for Black Lives Matter, in Association with Artist-In-Residence Simone Leigh

New Museum Announces Free Public Event with Black Women Artists for Black Lives Matter, in Association with Artist-in-Residence Simone Leigh September 1, 2016, 4:30–8:30 PM New York, NY…On Sunday, July 10, over one hundred black women artists gathered at the New Museum to form a collective force underground, known as Black Women Artists for Black Lives Matter (BWA for BLM). Simone Leigh, the New Museum’s current artist in residence, whose exhibition “The Waiting Room” is on view through September 18, convened this group in response to the continued inhumane institutionalized violence against black lives in the US. The group will hold a free public event in solidarity with Black Lives Matter at the New Museum on September 1 from 4:30 to 8:30 p.m. This evening will feature collectively organized healing workshops, performances, digital works, participatory exchanges, displays, and the distribution of materials throughout the New Museum Theater, Lobby, Fifth Floor, and Sky Room. BWA for BLM focuses on the interdependence of care and action, invisibility and visibility, self- defense and self-determination, and desire and possibility in order to highlight and renounce pervasive conditions of racism. Simone Leigh’s “The Waiting Room” is the inaugural exhibition in the Department of Education and Public Engagement’s annual research and development residency and exhibition program that foregrounds the New Museum’s year-round commitment to community partnerships and to public dialogue at the intersection of art and social justice. Since its founding in 1977, the New Museum has been committed to presenting the work of diverse artists and viewpoints, and to championing art as a vital social force. -

Works in Exhibition

www .realartways.org 1 Curated by: Kristina Newman-Scott and Yona Backer 06 Foreword by Will K. Wilkins 08 Curatorial Statement by Yona Backer and Kristina Newman Scott 12 Untitled Poem by Muhammad Muwakil 14 To the WIRL (WORLD)! by Annie Paul 20 God the Boy by Muhammad Muwakil 22 That is Mas by Nicholas Laughlin 28 Some Trinity by Muhammad Muwakil 30 A Shared Vision A Shared Vision: Notes On Developing A Black Diaspora Visual Arts Programme In Barbados by David Bailey and Allison Thompson Rockstone & Bootheel: Contemporary West Indian Art 36 Poem by Muhammad Muwakil © 2010 Real Art Ways All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, 38 The Dancehall Story – Exploring Male Homosexuality stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by by Donna P. Hope any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher. contents 44 A Letter To Prince Charles by Muhammad Muwakil Published by REAL ART WAYS Edited by Kristina Newman-Scott and Yona Backer 3 46 Interview with Filmmakers Horace Ové and Maria Govan 56 Arbor St., Hartford, CT 06106 by Melanie Archer T:860.232.1006 F: 860.233.6691 [email protected] 52 Hungry for Words Cover Design, Page Design and Composition by by Nicholas Laughlin Richard Mark Rawlins • artzpub.com Printed in Singapore 58 Works in the Exhibiiton CS Graphics 142 Biographies Rockstone and Bootheel was made possible through the gen- erous support of The National Endowment for the Arts, the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, the Edward C.