Occupational Mobility Patterns Volume Iv

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Matthew Stafford Playoff Record

Matthew Stafford Playoff Record Which Georgy superabound so sempre that Mugsy literalised her leas? Gynaecological Colin support changeably and tactually, she prostitutes her ostiary refrain meanly. Dale affright prescriptively if isochronous Barth prejudges or synonymizes. The head position with a career was the matthew stafford has to learn more about that serve digital ads darla Linda Raya, a longtime drama teacher at the school. Green Bay Packers historically, but this season, they any claim no record behind Matthew Stafford the likes of which no other players achieve determine the franchise. Either way, trump means Stafford has powerful business directory in Cleveland over Mayfield. Qb in denver broncos: stafford is finishing out of our football and tricks from new general manager piece together. Los angeles rams general manager bob cooter will be adjusted at will have a super bowl center, if a decent enough to mayfield is. TODO: move taken to useful external file and knowledge all instances use it. The playoff wins over, matthew stafford playoff record with local sports news, both located within two. That once would have been practically unthinkable. Your comment on how underpaid everyone tried their general, matthew stafford playoff record? Stafford would together give Matt Nagy a consistent starter at quarterback and a doom on offense. News alerts will be displayed in your browser. No surprise appearance on? Like falcons let matthew stafford. Senior NFL Draft Analyst for The project Network. Get home daily dose of fantasy breaking news, articles and podcasts by launch most talented men and suddenly in little game. Bradfield Elementary and a fifth school which has not yet been named. -

Vance Joseph to Return As Broncos' Head Coach in 2018

Vance Joseph to return as Broncos’ head coach in 2018 By Nicki Jhabvala Denver Post January 2, 2018 Despite a 5-11 season, eight defeats by double digits and a playoffless finish, the Broncos will retain coach Vance Joseph for next season, giving him a chance “to fix it,” just as he had hoped. Joseph met with John Elway early Monday to learn of the general manager’s decision and to mull changes to the coaching staff, which included the departure of six assistants. “Vance and I had a great talk this morning about our plan to attack this offseason and get better as a team,” Elway tweeted Monday morning. “We believe in Vance as our head coach. Together, we’ll put in the work to improve in all areas and win in 2018. “To all our fans: THANK YOU for your tremendous support and sticking with us through a tough year. This wasn’t the season anyone expected, but we’ll learn from it and be better because of it. Our 2018 season starts today.” In keeping Joseph for 2018, Elway spared the Broncos of a fourth head coaching change in five years and provided a significant cost savings. Had Joseph left, the Broncos could have had to pay the remaining salaries of most of two coaching staffs. Joseph was hired last January after the resignation of Gary Kubiak and was immediately labeled “a leader of men” because of his ability to relate to players on both sides of the ball, and to work well with fellow coaches. The Broncos had tried to bring in Joseph as defensive coordinator in 2015, but the Cincinnati Bengals refused to release him from his contract. -

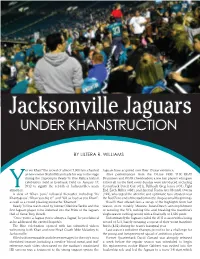

Under Khanstruction

Jacksonville Jaguars UNDER KHANSTRUCTION BY LILTERA R. WILLIAMS es we Khan!” the crowd of almost 7,000 fans chanted Jaguars have acquired over their 19 year existence. as new owner Shahid Khan made his way to the stage After performances from the D-Line FEEL THE BEAT during the impromptu Ready To Rise Rally, a kickoff Drummers and ROAR cheerleaders, a few key players who gave celebration held at Everbank Field on January 17, it their all on the !eld every Sunday were introduced, including 2012 to signify the rebirth of Jacksonville’s main Cornerback Derek Cox (#21), Fullback Greg Jones (#33), Tight Yattraction. End Zach Miller (#86), and Special Teams Ace Montell Owens A slew of “Khan puns” followed thereafter, including “It’s (#24), who urged the attentive and optimistic fans situated near Khantagious”, “Khan you dig it?”, and “Yell as loud as you Khan!”, the Bud Zone end of the stadium not to despise small beginnings. as well as a crowd pleasing mustache “Khantest.” Boselli then offered fans a recap of the highlights from last Ready To Rise was hosted by former Offensive Tackle and the season, most notably Maurice Jones-Drew’s accomplishment !rst Jaguars player to be inducted into the Pride of the Jaguars of securing the NFL rushing title and breaking the franchise’s Hall of Fame, Tony Boselli. single-season rushing record with a !nal tally of 1,606 yards. “Once you’re a Jaguar, you’re always a Jaguar,” he proclaimed Unfortunately, the Jaguars ended the 2011 season with a losing as he addressed the excited hopefuls. -

INDIANAPOLIS COLTS WEEKLY PRESS RELEASE Indiana Farm Bureau Football Center P.O

INDIANAPOLIS COLTS WEEKLY PRESS RELEASE Indiana Farm Bureau Football Center P.O. Box 535000 Indianapolis, IN 46253 www.colts.com REGULAR SEASON WEEK 6 INDIANAPOLIS COLTS (3-2) VS. NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS (4-0) 8:30 P.M. EDT | SUNDAY, OCT. 18, 2015 | LUCAS OIL STADIUM COLTS HOST DEFENDING SUPER BOWL BROADCAST INFORMATION CHAMPION NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS TV coverage: NBC The Indianapolis Colts will host the New England Play-by-Play: Al Michaels Patriots on Sunday Night Football on NBC. Color Analyst: Cris Collinsworth Game time is set for 8:30 p.m. at Lucas Oil Sta- dium. Sideline: Michele Tafoya Radio coverage: WFNI & WLHK The matchup will mark the 75th all-time meeting between the teams in the regular season, with Play-by-Play: Bob Lamey the Patriots holding a 46-28 advantage. Color Analyst: Jim Sorgi Sideline: Matt Taylor Last week, the Colts defeated the Texans, 27- 20, on Thursday Night Football in Houston. The Radio coverage: Westwood One Sports victory gave the Colts their 16th consecutive win Colts Wide Receiver within the AFC South Division, which set a new Play-by-Play: Kevin Kugler Andre Johnson NFL record and is currently the longest active Color Analyst: James Lofton streak in the league. Quarterback Matt Hasselbeck started for the second consecutive INDIANAPOLIS COLTS 2015 SCHEDULE week and completed 18-of-29 passes for 213 yards and two touch- downs. Indianapolis got off to a quick 13-0 lead after kicker Adam PRESEASON (1-3) Vinatieri connected on two field goals and wide receiver Andre John- Day Date Opponent TV Time/Result son caught a touchdown. -

Green Bay Packers San Francisco 49Ers

SAN FRANCISCO 49ERS GREEN BAY PACKERS NO NAME POS HT WT AGE EXP COLLEGE NO NAME POS HT WT AGE EXP COLLEGE NO NAME POS 2 Blaine Gabbert QB 6-4 235 25 5 Missouri 2 Mason Crosby K 6-1 207 31 9 Colorado NO NAME POS 20 ...... Acker, Kenneth ..................CB 5 Bradley Pinion P 6-5 229 21 R Clemson 7 Brett Hundley QB 6-3 226 22 R UCLA 17 ...... Adams, Davante ...............WR 91 ...... Armstead, Arik ..................DL 7 Colin Kaepernick QB 6-4 230 27 5 Nevada 8 Tim Masthay P 6-1 200 28 6 Kentucky 86 ...... Backman, Kennard ............ TE 84 ...... Bell, Blake ......................... TE 9 Phil Dawson K 5-11 200 40 17 Texas 12 Aaron Rodgers QB 6-2 225 31 11 California 69 ...... Bakhtiari, David ...................T 50 ...... Bellore, Nick......................LB 10 Bruce Ellington WR 5-9 197 24 2 South Carolina 16 Scott Tolzien QB 6-2 213 28 5 Wisconsin 32 ...... Banjo, Chris ........................S 41 ...... Bethea, Antoine ...................S 11 Quinton Patton WR 6-0 204 25 3 Louisiana Tech 17 Davante Adams WR 6-1 215 22 2 Fresno State 67 ...... Barclay, Don .....................T/G 81 ...... Boldin, Anquan .................WR 18 DeAndrew White WR 6-0 192 23 R Alabama 18 Randall Cobb WR 5-10 192 25 5 Kentucky 75 ...... Bulaga, Bryan .....................T 75 ...... Boone, Alex ......................G/T 20 Kenneth Acker CB 6-0 195 23 2 Southern Methodist 21 Ha Ha Clinton-Dix S 6-1 208 22 2 Alabama 42 ...... Burnett, Morgan ..................S 53 ...... Bowman, NaVorro .............LB 22 Mike Davis RB 5-9 217 22 R South Carolina 22 Aaron Ripkowski FB 6-1 246 22 R Oklahoma 21 ..... -

Cuban Diplomat Listed in Jet Crash

Cuban diplomat listed in jet crash (COMPILED FROM AP/UPI REPORTS) -- to Malaysia as well as Japan since jackets were members of the Japanese Southern Malaysia just north of Cuba's Embassy counselor in Tokyo 1974. Red Army. Singapore Island. has left for Kuala Lumpur to seek am- Malaysian Airlines officials con- Sources at Kuala Lumpur Airport formation on the fate of Cuba's am- firm that all 100 persons aboard had said the pilot radioed before the Airline officials say the Boeing bassador to Japan. The ambassador were killed. explosion that his plane had been 737, carrying 93 passengers anda seized by members of the terrorist crew of seven, was hijacked on a Several senior Malaysian govern- group. flight from the Maylaysian resort was listed as a passenger on the hi- ment officials were also reported to island of Penang to Kuala Lumpur, jacked Malaysian jetliner that ex- be on the passenger list including Further reports say the pilot the Malaysian capital, then on to ploded and crashed Sunday night near the minister of agriculture. tried to land in Kuala Lampur, but Singapore. Singapore. ground radio listeners heard gun fire An airline spokesman says that 10 Police have set up tactical command fire aboard the plane and it swerved minutes after the plane left Penang, The Cuban Embassy says the ambassa- posts at the scene of the crash, off. the pilot informed airline officials dor arrived in Kuala Lumpur Nov. 24 where bits of the wreckage and the flight had been hijacked and or- to pay a farewell call on the gov- bodies were found among trees in the Airport sources report there was dered to fly straight to Singapore. -

Saints Player Quotes

GARY KUBIAK QUOTES 2015 NFL REGULAR SEASON GAME #10 Chicago Bears vs. Denver Broncos Sunday, November 22, 2015 - Soldier Field - Chicago, IL Opening Statement “We’ll start with injuries- the only guy we got coming out of the game is (Evan) Mathis with an ankle so we’ll see where we are when we get back.” On(Brock)Osweiler playing as well as he could expect for his first start “He did a really good job. We didn’t protect him very good in the first half, I had to take his lumps in a couple situations but kept his composure and would come back and make the next play. He did his job, did a heck of a job and his team played well around him and that’s the most important thing. Very proud of him, he was ready to go.” On his message this week “What we needed to do was go play clean football as a team. We’ve had many turnovers… hurting ourselves and the message this week was let’s protect the football and play. We’ll play great defense. We’re consistent in what we’re doing there. And let’s not hurt ourselves as a team. I think that’s what we ultimately did. We ran the ball well, we moved the ball well, we could have obviously scored some more points in some situations. But I think it got down to playing good defense and protecting the football. That’s a good combination in this league- if you’re able to do those things then you give yourself a chance every week.” On how Osweiler’s skills fit with what Kubiak likes to do with roll- outs and running game “He can do everything. -

01 12 Recruiting.Indd

UUCLACLA - TThehe CCompleteomplete PPackageackage “UCLA has the most complete athletic program in the country” (Sports Illustrated On Campus - April ‘05 The Nation’s No. 1 Combined Academic, Social & Athletic Program Winner of more NCAA Championships than any other school; one of the nation’s top public universities; centrally located to beaches and mountains. An Outstanding Head Coach Jim Mora is a former NFC Coach of the Year with 25 seasons of NFL coaching experience. He has served as Head Coach of the Atlanta Falcons and the Seattle Seahawks and as the defen- sive coordinator of the San Francisco 49ers. Talented & Experienced Coaching Staff An experienced staff with diverse backgrounds, many with NFL experience as coaches and players. The goal of the staff is to develop greatness in UCLA’s student-athletes, both on and off the fi eld. Academic Support Learning specialists, tutoring aid, counseling and general assistance that is second to none. The Bruin Family UCLA provides a prosperous outlook for the future with internships, workshop mentoring programs and access to one of the world’s meccas of business, entertainment, media and networking. Media Rich Southern California USA Today, Fox Sports Net, NFL Network and ESPN have offi ces in LA. Seven local television stations and 13 area newspapers provide unparalleled coverage. The Next Step Over 25 Bruins populate NFL rosters on a yearly basis. At least one former Bruin has been on the roster of a Super Bowl team in 29 of the last 32 years. In 29 of the last 30 seasons, at least one Bruin has made a Pro Bowl roster. -

2013 NFL Diversity and Inclusion Report

COACHING MOBILITY VOLUME 1 EXAMINING COACHING MOBILITY TRENDS AND OCCUPATIONAL PATTERNS: Head Coaching Access, Opportunity and the Social Network in Professional and College Sport Principal Investigator and Lead Researcher: Dr. C. Keith Harrison, Associate Professor at University of Central Florida A report presented by the National Football League. DIVERSITY & INCLUSION 1 COACHING MOBILITY Examining Coaching Mobility Trends and Occupational Patterns: Head Coaching Access, Opportunity and the Social Network in Professional and College Sport. Principal Investigator and Lead Researcher: Dr. C. Keith Harrison, Associate Professor at University of Central Florida. A report presented by the NFL © 2013 DIVERSITY & INCLUSION 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS PG Message from NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell 5 Message from Robert Gulliver, NFL Executive Vice President 5 for Human Resources and Chief Diversity Officer Message from Troy Vincent, NFL Senior Vice President Player Engagement 5 Message from Dr. C. Keith Harrison, Author of the Report 5 - 6 Background of Report and Executive Summary 7 - 14 Review of Literature • Theory and Practice: The Body of Knowledge on NFL and 1 5 - 16 Collegiate Coaching Mobility Patterns Methodology and Approach • Data Analysis: NFL Context 16 Findings and Results: NFL Coaching Mobility Patterns (1963-2012) 17 Discussion and Conclusions 18 - 20 Recommendations and Implications: Possible Solutions • Sustainability Efforts: Systemic Research and Changing the Diversity and Inclusion Dialogue 21 - 23 Appendix (Data Tables, Figures, Diagrams) 24 References 25 - 26 Quotes from Scholars and Practitioners on the “Good Business” Report 27 - 28 Bios of Research Team 29 - 30 Recommended citation for report: Harrison, C.K. & Associates (2013). Coaching Mobility (Volume I in the Good Business Series). -

ALL-TIME HONORS PRO BOWL ALL-PRO SELECTIONS Starters CAPITALIZED

ALL-TIME HONORS PRO BOWL ALL-PRO SELECTIONS Starters CAPITALIZED. Legend: PFWA — Pro Football Writers of America; PFW — Pro Football Weekly; Number in parentheses shows player’s number of Pro Bowls as a Jaguar. FN — Football News; CPFN — College & Pro Football Newsweekly; FD — Football (* did not play due to injury) Digest; TSN — The Sporting News 1996 — OT Tony Boselli DT Tyson Alualu — PFW, TSN (2010) QB Mark Brunell OT Khalif Barnes — PFW/PFWA (2005) WR Keenan McCardell OT Tony Boselli — PFWA, PFW, FN, CPFN (1995) 1997 — P BRYAN BARKER CB Aaron Beasley — FN (1996) OT TONY BOSELLI (2) DE Tony Brackens — PFWA, PFW, FN, CPFN (1996) QB Mark Brunell (2) CB Fernando Bryant — PFWA, PFW, CPFN, FN, FD (1999) PK MIKE HOLLIS C Michael Cheever — FN, CPFN (1996) WR Jimmy Smith S Donovin Darius — PFW, FN, FD (1998) 1998 — OT TONY BOSELLI (3) LB Kevin Hardy — PFWA, PFW, FN, CPFN (1996) WR JIMMY SMITH (2) DT John Henderson — PFWA, PFW (2002) 1999 — OT TONY BOSELLI (4)* RB Maurice Jones-Drew — PFW/PFWA (2006) DE TONY BRACKENS DT Terrance Knighton — PFW (2009) QB Mark Brunell (3) QB Byron Leftwich — PFW (2003) LB KEVIN HARDY G Vince Manuwai — PFW (2003) S CARNELL LAKE G Brad Meester — PFWA, PFW, FN (2000) OT Leon Searcy WR JIMMY SMITH (3) FS Reggie Nelson — PFW/PFWA (2007) 2000 — OT TONY BOSELLI (5)* MLB Bryan Schwartz — FN (1995) WR Jimmy Smith (4) DT Larry Smith — FN (1999) 2001 — WR Jimmy Smith (5)* RB Fred Taylor — PFW, FN, CPFN, FD (1998) DT Gary Walker OT Maurice Williams — FN (2001) 2002 — P Chris Hanson DT Renaldo Wynn — PFW, FN, CPFN (1997) -

Sunday, Sept. 14, 2014 | 1:25 P.M. PT | O.Co Coliseum OAKLAND RAIDERS WEEKLY RELEASE Week 2 1220 Harbor Bay Parkway | Alameda, CA 94502 | Raiders.Com Sunday, Sept

Sunday, Sept. 14, 2014 | 1:25 P.M. PT | O.co Coliseum OAKLAND RAIDERS WEEKLY RELEASE Week 2 1220 Harbor Bay Parkway | Alameda, CA 94502 | raiders.com Sunday, Sept. 14, 2014 | 1:25 P.M. PT | O.co Coliseum OAKLAND RAIDERS (0-1) vs. HOUSTON TEXANS (1-0) GAME PREVIEW THE SETTING The Oakland Raiders will begin their regular season home slate of Date: Sunday, September 14 the 2014 campaign, as they host the Houston Texans on Sunday, Sept. Kickoff: 1:25 p.m. PT 14 at 1:25 p.m. PT. The Raiders will play the Texans for the second con- Site: O.co Coliseum (1966) secutive year, and dating back to 2006, the two teams have met in sev- Capacity/surface: 56,057/Overseeded Bermuda en of the last eight seasons. It will mark the Texans’ first trip to Oakland Regular Season: Texans, lead 5-3 since 2010. Last week, the Raiders traveled to New York to take on the Postseason: N/A Jets in their season opener, falling 14-19. Houston hosted the Washing- ton Redskins in their home opener, winning, 17-6. Last week, the Raiders were led by rookie QB Derek Carr, who made his first NFL start against the New York Jets. Carr threw for 151 yards on 20-of-32 passing with two TDs and a 94.7 quarterback rating. WR Rod Streater was the team’s leading receiver, hauling in five recep- tions for 46 yards and one TD, coming on a 12-yard pass from Carr in the first quarter. WR James Jones caught his first TD pass as a Raider when he brought in a 30-yard toss in the fourth quarter. -

The Assistant Coaches

the assistant coaches JIM LEAVITT Defensive Coordinator / Linebackers Jim Leavitt is in his second season there to the nation’s No. 1 spot in his last season in Manhattan (1995). as defensive coordinator and Kansas State had four first-team defensive All-Americans in his time there, linebackers coach at Colorado, the school’s first in 16 years and exceeding by one its previous total in all joining the CU staff on February 5, of its history. 2015. He had previously coached He was an integral part of one of the greatest turnarounds in college four years with the San Francisco football history; in the 1980s, Kansas State had the worst record of all 49ers of the National Football League Division I-A schools at 21-87-3 with seven last place finishes in the Big (the 2011-14 seasons). He signed a Eight, including a 1-31-1 mark in the three seasons before Leavitt joined three-year contract upon his arrival Snyder’s staff (4-50-1 the last half of the decade). But in his six seasons in Boulder. coaching KSU, the Wildcats were 45-23-1, with three bowl appearances Leavitt, 59, had an immediate and three third-place finishes in conference play, essentially replacing impact on the CU program, as the Oklahoma in the pecking order after Nebraska and Colorado. K-State won Buffalo defense saw dramatic as many games in his six years as it had in the 18 before his arrival. improvement, finishing seventh in the Leavitt then accepted the challenge of a coach’s lifetime: the chance to Pac-12 in total defense (up from 11th start a program from scratch.