Life Around the Juniper Forest How Juniper Forests Contribute to Well Being of Communities in Ziarat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monitoring Carbon Stock and Land-Use Change in 5000-Year-Old Juniper Forest Stand of Ziarat, Balochistan, Through a Synergistic Approach

Article Monitoring Carbon Stock and Land-Use Change in 5000-Year-Old Juniper Forest Stand of Ziarat, Balochistan, through a Synergistic Approach Hamayoon Jallat 1 , Muhammad Fahim Khokhar 1,* , Kamziah Abdul Kudus 2 , Mohd Nazre 2 , Najam u Saqib 1, Usman Tahir 3 and Waseem Razzaq Khan 2,4,* 1 Institute of Environmental Science and Engineering, National University of Science and Technology, Islamabad 44000, Pakistan; [email protected] (H.J.); [email protected] (N.u.S.) 2 Department of Forest Science & Biodiversity, Faculty of Forestry and Environment, Universiti Putra Malaysia, UPM Serdang, Selangor 43400, Malaysia; [email protected] (K.A.K.); [email protected] (M.N.) 3 Department of Forest Sciences, Chair of Tropical and International Forestry, Faculty of Environmental Science, Technische Universität, 01069 Dresden, Germany; [email protected] 4 Institut Ecosains Borneo, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Bintulu Kampus, Sarawak 97008, Malaysia * Correspondence: [email protected] (M.F.K.); [email protected] (W.R.K.); Tel.: +92-51-9085-4308 (M.F.K.); +60-19-3557-839 (W.R.K.) Abstract: The Juniper forest reserve of Ziarat is one of the biggest Juniperus forests in the world. This study assessed the land-use changes and carbon stock of Ziarat. Different types of carbon pools were quantified in terms of storage in the study area in tons/ha i.e., above ground, soil, shrubs and litter. The Juniper species of this forest is putatively called Juniperus excelsa Beiberstein. To estimate above- ground biomass, different allometric equations were applied. -

THE PROBLEM of PIKA CONTROL in BALUCWSTAN, PAKISTAN ABDUL AZIZ KHAN and WILLIAM R

THE PROBLEM OF PIKA CONTROL IN BALUCWSTAN, PAKISTAN ABDUL AZIZ KHAN and WILLIAM R. SMYTHE, Vertebrate Pest Control Centre. Karachi University Campus. Karachi 32. Pakistan ABSTRACT: The collared pika, Ochotona rufescens has been recorded as a serious pest in apple orchards in the uplands valley of Ziarat in Baluchistan. In the winter, when the natural vegetation is lacking, the pikas debark the apple tree trunks or branches resulting in the killing of the tree and reduced fruit production. In sumner, damage to wheat, corn and potatoes is also very severe. It is estimated that pikas cause hundreds of thousands of dollars (US) in annual apple production losses. The apple production in Baluchistan accounts for about 35 percent of the total provincial income through food production. During the six years (1974-1979), the winter of 1973-74 was noted for heavy damage to apple trees and thereafter it declined steadily. The control measures evaluated were of various kinds among which repellent "Ostico" was very effective in protecting the trees. Poison baiting with brodifacoum (0.005%), Vacor (1%) and thallium sulphate (1%) were also effective in reducing the pika population. To alleviate damage caused by pikas, the fanners also practice some traditional protective methods which in some cases are quite effective but very laborious. INTRODUCTION The pikas, often called, "the piping hare", are little known as pests, generally confined to alpine rocky areas, often unsuitable for agricultural use. There are 15 species of the genus OchotoJa. one in the new world and 14 in the old world (Walker, Ma11111als of the World, John Hopkins Press, 1964 • Ochotona prince~s of the North American species has been relatively well studied (Johnson 1967,. -

Rahim Yar Khan District Is a District in the Punjab Province of Pakistan, the City of Rahim Yar Khan Is the Capital

World Water Day April-2011 17 DRINKING WATER QUALITY CHALLENGES IN PAKISTAN By Z. A. Soomro1, Dr. M. I. A. Khokhar, W. Hussain and M. Hussain Abstract: Pakistan is facing drastic decrease in per capita water availability due to rapid increase in population. The water shortage and increasing competition for multiple uses of water has adversely affected the quality of water. Pakistan Council of Research in Water Resources has launched a national water quality monitoring program. This program covered water sampling and their analysis from 21 major cities. The water samples were analyzed for physical, chemical and bacteriological contamination. Results showed that most of the samples in all four provinces are microbiologically contaminated. Arsenic problem is major in cities of Punjab, Nitrate contamination in Balochistan, Iron contamination in KPK and higher turbidity values found in water samples found in Sindh. This valuable data would serve the regulatory bodies and implementing authorities towards the quality drinking water supply. Key words: Water Quality, Surface water, Groundwater contamination, Hand pumps, Pollution, Microbiology, Chemical contamination. 1. INTRODUCTION Nature has blessed Pakistan with adequate surface and groundwater resources. However, rapid population growth, urbanization and the continued industrial development has placed immense stress on water resources of the country. The extended droughts and non-development of additional water resources have further aggravated the water scarcity situation. Pakistan has been blessed with abundance of availability of surface and ground water resources to the tune of 128300 million m3 and 50579 million m3 per year respectively (The Pakistan National Conservation Strategy, 1992).Consequently per capita water availability has decreased from 5600 m3 to 1000 m3 / annum(Water quality status 2003). -

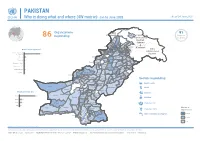

Pakistan: Who Is Doing What and Where (4W Matrix)

PAKISTAN Who is doing what and where (4W matrix)- Jan to June 2020 As of 24 June 2020 Organizations Khyber 91 responding Pakhtunkhwa Gilgit Pakistan Projects 86 Swat Administered in 2020 Upper Dir Kashmir ! ! ! ! ! Neelum ! ! ! Jammu ! ! Shangla ! ! ! ! ! Lower Dir ! ! ! ! Mansehra ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Tor ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Buner ! & ! ! ! Mohmand ! Ghar ! Mardan Muzaffarabad! ! ! Hattian! Kashmir ! ! Abbottabad ! Swabi ! Organizations by sector* Khyber Peshawar ! ! India Haripur Bagh Haveli! ! ! Nowshera ! Kurram Poonch! ! Administered ! Orakzai Islamabad Sudhnoti! Water, Sanitation ! Attock ! 76 Hangu Kohat Kotli ! Kashmir and Hygiene ! Rawalpindi ! ! ! Mirpur! ! ! ! Health 8 North Waziristan Bhimber! Bannu Chakwal Jhelum ! ! Mianwali Gujrat Nutrition 5 Lakki Marwat Mandi Bahauddin Sialkot Khushab South Waziristan Hafizabad Narowal Protection / GBV 3 Sargodha Dera Ismail Gujranwala Khan Sheikhupura Protection / CP 2 Sheerani Chiniot Bhakkar Nankana Sahib Lahore Food Security 2 Zhob Jhang Faisalabad Toba Tek Musakhel Layyah Logistics 1 Killa Saifullah Singh Pishin Sahiwal Okara Killa Abdullah Dera Ghazi Punjab Ziarat Khan Khanewal Loralai Pakpattan Quetta Harnai Multan Muzaffargarh Vehari Sectors responding Sibi Barkhan Mastung Kohlu Lodhran Bahawalnagar Nushki Rajanpur Food Security Kachhi Chagai PAKISTAN Dera Bugti Bahawalpur Health Nasirabad Kharan Jhal Magsi Sohbatpur Rahim Yar Kashmore Organizations by type Jacobabad Khan Jaffarabad Logistics Shikarpur Balochistan Qambar Ghotki NGO 60 Washuk Khuzdar Shahdadkot Nutrition -

Ziarat District Education Plan (2016-17 to 2020-21)

Ziarat District Education Plan (2016-17 to 2020-21) Table of Contents LIST OF ACRONYMS 1 LIST OF FIGURES 3 LIST OF TABLES 4 1 INTRODUCTION 5 2 METHODOLOGY & IMPLEMENTATION 7 3 LASBELA DISTRICT PROFILE 10 3.1 POPULATION 11 3.2 ECONOMIC ENDOWMENTS 11 3.3 POVERTY & CHILD LABOR: 12 3.4 STATE OF EDUCATION 12 4 ACCESS & EQUITY 14 4.1 EQUITY AND INCLUSIVENESS 18 4.2 IMPORTANT FACTORS 19 4.2.1 SCHOOL AVAILABILITY AND UTILIZATION 19 4.2.2 MISSING FACILITIES AND SCHOOL ENVIRONMENT 20 4.2.3 POVERTY 21 4.2.4 COMMUNITY INVOLVEMENT AND PARENT’S ILLITERACY 21 4.2.5 ALTERNATE LEARNING PATH 21 4.3 OBJECTIVES AND STRATEGIES 22 4.3.1 OBJECTIVE: PROVISION OF EDUCATION OPPORTUNITIES TO EVERY SETTLEMENT 22 4.3.2 OBJECTIVE: INCREASED UTILIZATION OF EXISTING SCHOOLS 22 4.3.3 OBJECTIVE: REDUCE MISSING FACILITIES AND BRING SCHOOLS UP TO A MINIMUM STANDARD ERROR! BOOKMARK NOT DEFINED. 4.3.4 OBJECTIVE: REDUCE OOSC THROUGH ALTERNATE LEARNING PATH (RE-ENTRY OF OOSC IN MAINSTREAM THROUGH ALP) ERROR! BOOKMARK NOT DEFINED. 4.3.5 OBJECTIVE: REDUCE ECONOMIC BARRIERS TO SCHOOL ENTRY AND CONTINUATION ERROR! BOOKMARK NOT DEFINED. 4.3.6 OBJECTIVE: IMPROVE SERVICE DELIVERY FOR INCLUSIVE EDUCATION ERROR! BOOKMARK NOT DEFINED. 5 DISASTER RISK REDUCTION 22 5.1 OBJECTIVES AND STRATEGIES 26 5.1.1 OBJECTIVE: DEVELOP & IMPLEMENT DISTRICT DRR PLAN ERROR! BOOKMARK NOT DEFINED. 6 QUALITY AND RELEVANCE OF EDUCATION 27 6.1 SITUATION 27 6.2 DISTRICT LIMITATIONS AND STRENGTHS 28 6.3 OVERARCHING FACTORS FOR POOR EDUCATION 30 6.4 DISTRICT RELATED FACTORS OF POOR QUALITY 30 6.4.1 OWNERSHIP -

Jud Camp Locations

PAKISTAN TAJIKISTAN TURKMENISTAN UZBEKISTAN CHINA Legend HunzaHunza NagarNagar Country capital GhizerGhizer ChitralChitral Province borders GilgitGilgit Distric borders NORTHERN AREAS DiamerDiamer SkarduSkardu Rivers u N.W.F.P. GhancheGhanche M rgh Swat ab Upper Dir KohistanKohistan AstoreAstore Flood affected Districts Upper Dir Neelum Swat Shangla Neelum Batagram Bajaur Lower Dir ShanglaBatagram Known Jamaat-ud-Dawa BajaurLower Dir Har KABUL MalakandMalakand Mansehra i Rud Mohmand Buner Mansehra AZAD KASHMIR Mohmand MardanMardan Buner (alias Falah-e-Insaniat MuzaffarabadMuzaffarabad I n Abbottabad Charsadda Swabi AbbottabadHattianHattian d Foundation) aid camps Charsadda Swabi u PeshawarPeshawar HaripurHaripur Bagh HaveliHaveli s KhyberKhyber Nowshera ISLAMABADPoonch d F.A.T.A. Nowshera SudhnotiSudhnoti Poonch n Orakzai a KurramKurram ISLAMABAD CAPITAL TERRITORY lm Attock Kotli e HanguHangu KohatKohat Rawalpindi Kotli H Attock Rawalpindi MirpurMirpur KarakKarak Bhimber AFGHANISTAN North Waziristan Bhimber North Waziristan Chakwal JhelumJhelum BannuBannu Mianwali Chakwal Gujrat Gujrat Ch en LakkiLakki Marwat Marwat MandiMandi Sialkot a South Waziristan BahauddinBahauddin Sialkot b NarowalNarowal South Waziristan TankTank KhushabKhushab GujranwalaGujranwala SargodhaSargodha Dera HafizabadHafizabad IRAN IsmailDera Khan Ismail Khan SheikhupuraSheikhupura ChiniotChiniot ShernaiShernai BhakkarBhakkar Nankana Nankana LahoreLahore SahibSahib ZhobZhob Faisalabad JhangJhang Faisalabad Qilla Abdullah Qilla Saifullah Qilla Saifullah LayyahLayyah -

Hydrogeochemical Investigations of Groundwater in Ziarat Valley, Balochistan

PINSTECH-216 HYDROGEOCHEMICAL INVESTIGATIONS OF GROUNDWATER IN ZIARAT VALLEY, BALOCHISTAN Waheed Akram Manzoor Ahmad Muhammad Rafique Isotope Application Division Directorate of Technology Pakistan Institute of Nuclear Science and Technology Nilore, Islamabad March, 2010 ABSTRACT Present study was undertaken in Ziarat Valley, Baluchistan to investigate recent trends of groundwater chemistry (geochemical facies, geochemical evolution) and assess the groundwater quality for drinking and irrigation purposes. For this purpose samples of groundwater (open wells, tubewells, karezes, springs) were periodically collected from different locations and analyzed for dissolved chemical constituents such as sodium, potassium, magnesium, calcium, carbonate, bicarbonate, chloride and sulphate. The data indicated that concentrations of sodium, potassium, calcium and magnesium vary from 5 to 113, 0.3 to 3, 18 to 62 and 27 to 85 mg/1 respectively. Values of anions i. e. bicarbonate, chloride and sulphate lie in the range of 184 to 418, 14 to 77 and 8 to 318 mg/1 respectively. Hydrogeochemical facies revealed that groundwater in the study area belongs to Mg-HCC^ type at 72% surveyed locations. Dissolution and calcite precipitation were found to be the main processes controlling the groundwater chemistry. Chemical quality was assessed for drinking use by comparing with WHO, Indian and proposed national standards, and for irrigation use using empirical indices such as SAR and RSC. The results show that groundwater is quite suitable for irrigation and drinking purposes. CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. CLIMATE 2 3. GEOLOGY 2 4. MATERIALS AND METHODS 3 4.1 Sample Collection 3 4.2 Analyses 3 5. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION 4 5.1 Chemical Characteristics of Groundwater 4 5.2 Hydrogeochemical Facies of Groundwater 5 5.3 Geochemical Evolution of Groundwater 6 5.4 Evaluation of Groundwater Quality 7 5.4.1 Drinking use 7 5.4.2 Irrigation use 10 6. -

Fluoride in the Drinking Water of Pakistan and The

History of Geo- and Space Open Access Open Sciences Advances in Science & Research Open Access Proceedings Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Drink. Water Eng. Sci. Discuss.,Drinking 5, 495–514, 2012 Water Drinking Water www.drink-water-eng-sci-discuss.net/5/495/2012/ DWESD doi:10.5194/dwesd-5-495-2012 Engineering and Science Engineering and Science © Author(s) 2012. CC Attribution 3.0 License. 5, 495–514, 2012 Open Access Access Open Discussions This discussion paper is/has been under review for the journal Drinking Water Engineering and Fluoride in the Science (DWES). Please refer to the corresponding final paper in DWES if available. Discussions Earth System Earth System drinking water of Pakistan Science Science M. A. Tahir and H. Rasheed Open Access Open Fluoride in theAccess Open Data drinking water ofData Pakistan and the possible risk of crippling fluorosis Title Page Abstract Introduction M. A. Tahir and H. Rasheed Conclusions References Pakistan Council of Research in Water Resources, Kheyaban-e-Johar, H-8/1, Islamabad, Pakistan Tables Figures Received: 3 February 2012 – Accepted: 7 February 2012 – Published: 7 September 2012 Correspondence to: M. A. Tahir ([email protected]) J I Published by Copernicus Publications on behalf of the Delft University of Technology. J I Back Close Full Screen / Esc Printer-friendly Version Interactive Discussion 495 Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Abstract DWESD To explore the possibility of fluoride toxicity, seven hundred and forty seven (747) wa- ter samples were collected from surface and ground water sources of sixteen major 5, 495–514, 2012 cities of Pakistan, adopting a uniform sampling design with distribution of samples 5 as: Lahore (79), Kasur (46), Faisalabad (30), Khushab (50), Chakwal (51), Mianwali Fluoride in the (30), Jhelum (53), Bahawalpur (60), Karachi (60), Mirpur Khas (55), Peshawar (38), drinking water of Risalpur (35), Quetta (81), Ziarat (21), Loralai (21), Mastung (37). -

Geographical Distribution of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis and Sand Flies in Pakistan

Türkiye Parazitoloji Dergisi, 30 (1): 1 - 6, 2006 Acta Parasitologica Turcica © Türkiye Parazitoloji Derneği © Turkish Society for Parasitology Geographical Distribution of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis and Sand Flies in Pakistan Ashraf SHAKİLA1, Fatima Mujib BİLQEES2, Azra SALİM3, Moinuddin4 1Institute of Hematology, Baqai Medical Karachi, Pakistan, 2Department of Zoology Jinnah University for Women Karachi; 3Jinnah University for Women Karachi, Pakistan, 4Institute of Haematology Baqai Medical University, Pakistan SUMMARY: Cutaneous leishmaniasis is found in all the four provinces of Pakistan; these are NWFP, Balochistan, Sindh and Punjab. In Balochistan the areas from where the patients came are Uthal, Quetta and Ormara. The highest number of patients came from Quetta and least from Ormara. The patients included in this study were from the Mangopir and Chakewara, areas of Karachi. The infection is endemic in this country and the recent epidemics in the Dadu District and Nawabshah indicate its importance in the locality. The sand fly vector is found in all four provinces of Pakistan that are listed here. It is quite obvious that presence of leishmaniasis indicates the presence of sand flies and cutaneous leishmaniasis is more common. Key Words: Cutaneous Leishmaniasis, sand fly, geographical distribution, Pakistan Pakistan’da Kutanöz Leishmaniasis ve Kum Sineklerinin Coğrafik Dağılımı ÖZET: Kutanöz leishmaniasis, Pakistan’ın NWFP, Balochistan, Sindh ve Punjab bölgelerinde görülmektedir. Balochistan’da Uthal, Quetta ve Ormara bölgelerinden hastalar bulunmaktadır. En fazla hasta Quetta en az ise Ormara bölgesindendir. Bu çalışmaya alınan hastalar Karaçi’nin Mangopir ve Chakewara bölgelerindendir. Enfeksiyon bu ülkede endemiktir, Dadu Bölgesi ve Nawabshah’da mey- dana gelen son salgın enfeksiyonun bu lokalitelerde de önemli olduğunu göstermektedir. -

Audit Report on the Accounts of District Government Nowshera Audit Year 2017-18 Auditor General of Pakistan

AUDIT REPORT ON THE ACCOUNTS OF DISTRICT GOVERNMENT NOWSHERA AUDIT YEAR 2017-18 AUDITOR GENERAL OF PAKISTAN TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ..................................................................i Preface ...................................................................................................................... ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................... iii SUMMARY TABLES & CHARTS ...................................................................... vii I: Audit Work Statistics .......................................................................................... vii II: Audit observations Classified by Categories ..................................................... vii III: Outcome Statistics ........................................................................................... viii IV: Table of Irregularities pointed out .....................................................................ix V: Cost Benefit Ratio ...............................................................................................ix CHAPTER-1 ............................................................................................................. 1 1.1 District Government Nowshera ................................................................ 1 1.1.1 Introduction ............................................................................................... 1 1.1.2 Comments on Budget and Expenditure (Variance analysis) .................... 1 -

Find Address of Your Nearest Loan Center and Phone Number of Concerned Focal Person

Find address of your nearest loan center and phone number of concerned focal person Loan Center/ S.No. Province District PO Name City / Tehsil Focal Person Contact No. Union Council/ Location Address Branch Name Akhuwat Islamic College Chowk Oppsite Boys College 1 Azad Jammu and Kashmir Bagh Bagh Bagh Nadeem Ahmed 0314-5273451 Microfinance (AIM) Sudan Galli Road Baagh Akhuwat Islamic Muzaffarabad Road Near main bazar 2 Azad Jammu and Kashmir Bagh Dhir Kot Dhir Kot Nadeem Ahmed 0314-5273451 Microfinance (AIM) dhir kot Akhuwat Islamic Mang bajri arja near chambar hotel 3 Azad Jammu and Kashmir Bagh Harighel Harighel Nadeem Ahmed 0314-5273451 Microfinance (AIM) Harighel Akhuwat Islamic 4 Azad Jammu and Kashmir Bhimber Bhimber Bhimber Arshad Mehmood 0346-4663605 Kotli Mor Near Muslim & School Microfinance (AIM) Akhuwat Islamic 5 Azad Jammu and Kashmir Bhimber Barnala Barnala Arshad Mehmood 0346-4663605 Main Road Bimber & Barnala Road Microfinance (AIM) Akhuwat Islamic Main choki Bazar near Sir Syed girls 6 Azad Jammu and Kashmir Bhimber Samahni Samahni Arshad Mehmood 0346-4663605 Microfinance (AIM) College choki Samahni Helping Hand for Adnan Anwar HHRD Distrcict Office Relief and Hattian,Near Smart Electronics,Choke 7 Azad Jammu and Kashmir Hattian Hattian UC Hattian Adnan Anwer 0341-9488995 Development Bazar, PO, Tehsil and District (HHRD) Hattianbala. Helping Hand for Adnan Anwar HHRD Distrcict Office Relief and Hattian,Near Smart Electronics,Choke 8 Azad Jammu and Kashmir Hattian Hattian UC Langla Adnan Anwer 0341-9488995 Development Bazar, PO, Tehsil and District (HHRD) Hattianbala. Helping Hand for Relief and Zahid Hussain HHRD Lamnian office 9 Azad Jammu and Kashmir Hattian Hattian UC Lamnian Zahid Hussain 0345-9071063 Development Main Lamnian Bazar Hattian Bala. -

Weekly Epidemiological Bulletin Disease Early Warning System and Response in Pakistan

Weekly Bulletin Epidemiological Disease early warning system and response in Pakistan Volume 3, Issue 11, Wednesday 21 March 2012 Highlights Priority diseases under surveillance Epidemiological week no. 11 (11 to 17 March 2012) in DEWS Acute (Upper) Respiratory Infection • In week 11, 2012, total 85 districts including 3 agencies provided surveillance data to the Pneumonia DEWS on weekly basis from around 1,947 health facilities. Data from mobile teams is reported Suspected Diphtheria through sponsoring BHU or RHC. Suspected Pertussis Acute Watery Diarrhoea Bloody diarrhoea • A total of 689,606 consultations were reported through DEWS of which 23% were acute Other Acute Diarrhoea respiratory infections (ARI); 6% were acute diarrhoea; 4% were suspected malaria; while 4% were Suspected Enteric/Typhoid Fever Skin disease. Suspected Malaria Suspected Meningitis Suspected Dengue fever • A total of 204 alerts with 30 outbreaks were reported/identified in week 11, 2012: Alto‐ Suspected Viral Hemorrhagic Fever gether 89 alerts for Measles; 22 for Typhoid; 21 for Leishmaniasis; 17 for ARI; 10 for NNT and Pyrexia of Unknown Origin tetanus; 9 Pertussis; 7 for Scabies; 6 for AWD; 5 for AD; 4 for DF; 3 each for AJS, BD and Malaria; Suspected Measles Suspected Acute Viral Hepatitis 2 each for Diphtheria and Unexplained fever; while 1 for Rabies. Chronic Viral Hepatitis Neonatal Tetanus • As of 15 March 2012, the total number of polio cases confirmed by the laboratory is 14 Acute Flaccid Paralysis from 10 districts/towns/tribal agencies and areas. Scabies Cutaneous Leishmaniasis Others Figure‐1: Weekly trend of Acute diarrhoea, Bloody diarrhoea, ARI and Suspected malaria in Pakistan, Week‐1, 2011 to week‐11, 2012.