Summary Economic Impacts of Utah's Tech Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ebay Inc. Non-Federal Contributions: January 1 – December 31, 2018

eBay Inc. Non-Federal Contributions: January 1 – December 31, 2018 Campaign Committee/Organization State Amount Date Utah Republican Senate Campaign Committee UT $ 2,000 1.10.18 Utah House Republican Election Committee UT $ 3,000 1.10.18 The PAC MO $ 5,000 2.20.18 Anthony Rendon for Assembly 2018 CA $ 3,000 3.16.18 Atkins for Senate 2020 CA $ 3,000 3.16.18 Low for Assembly 2018 CA $ 1,000 3.16.18 Pat Bates for Senate 2018 CA $ 1,000 3.16.18 Brian Dahle for Assembly 2018 CA $ 1,000 3.16.18 Friends of John Knotwell UT $ 500 5.24.18 NYS Democratic Senate Campaign Committee NY $ 1,000 6.20.18 New Yorkers for Gianaris NY $ 500 6.20.18 Committee to Elect Terrence Murphy NY $ 500 6.20.18 Friends of Daniel J. O'Donnell NY $ 500 6.20.18 NYS Senate Republican Campaign Committee NY $ 2,000 6.20.18 Clyde Vanel for New York NY $ 500 6.20.18 Ben Allen for State Senate 2018 CA $ 1,000 6.22.18 Steven Bradford for Senate 2020 CA $ 1,000 6.22.18 Mike McGuire for Senate 2018 CA $ 1,000 6.22.18 Stern for Senate 2020 CA $ 1,000 6.22.18 Marc Berman for Assembly 2018 CA $ 1,000 6.22.18 Autumn Burke for Assembly 2018 CA $ 1,000 6.22.18 Ian Calderon for Assembly 2018 CA $ 1,000 6.22.18 Jim Cooper for Assembly 2018 CA $ 1,000 6.22.18 Tim Grayson for Assembly 2018 CA $ 1,000 6.22.18 Blanca Rubio Assembly 2018 CA $ 1,000 6.22.18 Friends of Kathy Byron VA $ 500 6.22.18 Friends of Kirk Cox VA $ 1,000 6.22.18 Kilgore for Delegate VA $ 500 6.22.18 Lindsey for Delegate VA $ 500 6.22.18 McDougle for Virginia VA $ 500 6.22.18 Stanley for Senate VA $ 1,000 6.22.18 Wagner -

Microsoft Corporate Political Contributions July 1, 2018 – December 31, 2018

Microsoft Corporation Tel 425 882 8080 One Microsoft Way Fax 425 936 7329 Redmond, WA 98052-6399 http://www.microsoft.com Microsoft Corporate Political Contributions July 1, 2018 – December 31, 2018 Name State Amount 2018 San Francisco Inaugural Fund CA $5,000 Democratic Attorneys General Assoc DC $25,000 Democratic Legisl Campaign Cmte DC $25,000 Democratic Governors Assoc DC $150,000 Global Women’s Innovation Network DC $15,000 Republican Attorneys General Assoc DC $25,000 Republican Governors Assoc DC $100,000 Ripon Society DC $35,000 Republican Legislative Campaign Committee DC $25,000 The Congressional Institute DC $27,500 Brady for Senate IL $2,500 Citizens for Chris Nybo IL $500 Citizens for Durkin IL $2,500 Citizens for John Cullerton for State Senate IL $3,000 Committee to Elect Keith Wheeler IL $500 Friends for State Rep Anthony DeLuca IL $500 Friends of Bill Cunningham IL $500 Friends of Jaime M Andrade Jr IL $500 Friends of Michael J. Madigan IL $3,000 Friends of Terry Link IL $1,000 Team Demmer IL $500 Zalewski for State Representative IL $750 Kansan's for Kobach, LLC KS $2,000 Freedom for all Massachusetts MA $5,000 Tate's PAC MS $1,000 Committee to Elect Ann Millner UT $500 Committee to Elect Brad Last UT $500 Committee to Elect Brad Wilson UT $500 Committee to Elect Brian King UT $500 Committee to Elect Craig Hall UT $500 Committee to Elect Curt Bramble UT $500 Committee to Elect Dan Hemmert UT $500 Committee to Elect Dan McCay UT $500 Committee to Elect Deidre Henderson UT $500 Committee to Elect Evan Vickers UT $500 -

FY 2019 Political Contributions.Xlsx

WalgreenCoPAC Political Contributions: FY 2019 Recipient Amount Arkansas WOMACK FOR CONGRESS COMMITTEE 1,000.00 Arizona BRADLEY FOR ARIZONA 2018 200.00 COMMITTE TO ELECT ROBERT MEZA FOR STATE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 200.00 ELECT MICHELLE UDALL 200.00 FRIENDS OF WARREN PETERSEN 200.00 GALLEGO FOR ARIZONA 1,000.00 JAY LAWRENCE FOR THE HOUSE 18 200.00 KATE BROPHY MCGEE FOR AZ 200.00 NANCY BARTO FOR HOUSE 2018 200.00 REGINA E. COBB 2018 200.00 SHOPE FOR HOUSE 200.00 VINCE LEACH FOR SENATE 200.00 VOTE HEATHER CARTER SENATE 200.00 VOTE MESNARD 200.00 WENINGER FOR AZ HOUSE 200.00 California AMI BERA FOR CONGRESS 4,000.00 KAREN BASS FOR CONGRESS 3,500.00 KEVIN MCCARTHY FOR CONGRESS 5,000.00 SCOTT PETERS FOR CONGRESS 1,000.00 TONY CARDENAS FOR CONGRESS 1,000.00 WALTERS FOR CONGRESS 1,000.00 Colorado CHRIS KENNEDY BACKPAC 400.00 COFFMAN FOR CONGRESS 2018 1,000.00 CORY GARDNER FOR SENATE 5,000.00 DANEYA ESGAR LEADERSHIP FUND 400.00 STEVE FENBERG LEADERSHIP FUND 400.00 Connecticut LARSON FOR CONGRESS 1,000.00 Delaware CARPER FOR SENATE 1,000.00 Florida BILIRAKIS FOR CONGRESS 1,000.00 DARREN SOTO FOR CONGRESS 1,000.00 DONNA SHALALA FOR CONGRESS 1,000.00 STEPHANIE MURPHY FOR CONGRESS 1,000.00 VERN BUCHANAN FOR CONGRESS 2,500.00 Georgia BUDDY CARTER FOR CONGRESS 4,000.00 Illinois 1 WalgreenCoPAC Political Contributions: FY 2019 Recipient Amount CHUY GARCIA FOR CONGRESS 1,000.00 CITIZENS FOR RUSH 1,000.00 DAN LIPINSKI FOR CONGRESS 1,000.00 DAVIS FOR CONGRESS/FRIENDS OF DAVIS 1,500.00 FRIENDS OF CHERI BUSTOS 1,000.00 FRIENDS OF DICK DURBIN COMMITTEE -

Essential Elements for Technology Powered Learning

UTAH‘S MASTER PLAN ESSENTIAL ELEMENTS FOR TECHNOLOGY POWERED LEARNING COMMUNICATION ★ TECHNICAL SUPPORT ★ INSTRUCTIONAL DESIGN INFRASTRUCTURE ★ PROJECT MANAGEMENT ★ DEVICE & SOFTWARE PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT ★ POLICY & PROCEDURE ★ PROCUREMENT DIGITAL CONTENT ★ RESEARCH & PROGRAM METRICS ★ LEADERSHIP v1.04 The Utah State Board of Education District 1: Terryl Warner District 9: Joel Wright District 2: Spencer F. Stokes District 10: Dave Crandall (Chair) District 3: Linda B. Hansen District 11: Jefferson Moss District 4: Dave Thomas (First Vice Chair) District 12: Dixie L. Allen District 5: Laura Belnap District 13: Stan Lockhart District 6: Brittney Cummins District 14: Mark Huntsman District 7: Leslie B. Castle District 15: Barbara Corry District 8: Jennifer A. Johnson (Second Vice Chair) The Digital Teaching and Learning Task Force Members David Thomas, Utah State Board of Education (Chair) Laura Belnap, Utah State Board of Education Stan Lockhart, Utah State Board of Education Ben Dalton, Garfield County School District Superintendent and UETN Board Member Cindy Nagasawa-Cruz, Jordan School District Technology Director and UETN Board Member Bryan Bowles, Davis School District Superintendent Terry Shoemaker, Wasatch School District Superintendent Rick Robins, Juab School District Superintendent Fred Donaldson, DaVinci Academy Executive Director Jim Langston, Tooele School District Technology Director Senator Howard Stephenson, Utah State Senate Representative John Knotwell, Utah House of Representatives Nolan Karras, Governor's Commission -

Minutes for 02/18

MINUTES OF THE HOUSE REVENUE AND TAXATION STANDING COMMITTEE Room 445, State Capitol February 18, 2014 Members Present: Rep. Ryan Wilcox, Chair Rep. Jim Nielson, Vice Chair Rep. Jake Anderegg Rep. Joel Briscoe Rep. Tim Cosgrove Rep. Steve Eliason Rep. Gage Froerer Rep. Francis Gibson Rep. Eric Hutchings Rep. Brian King Rep. John Knotwell Rep. Kay McIff Rep. Doug Sagers Rep. Jon Stanard Rep. Earl Tanner Members Absent: Rep. Mel Brown Staff Present: Mr. Leif G. Elder, Policy Analyst Ms. An Bradshaw, Secretary NOTE: A list of visitors and a copy of handouts are filed with the committee minutes. Chair Wilcox called the meeting to order at 2:11 p.m. MOTION: Rep. Stanard moved to approve the minutes of February 12, 2014. The motion passed unanimously with Rep. Cosgrove, Rep. Froerer, Rep. Gibson, Rep. Hutchings, Rep. McIff, and Rep. Tanner absent for the vote. S.B. 155 Apportionment of Income Amendments (Sen. C. Bramble) Sen. Bramble explained the bill to the committee. MOTION: Rep. Stanard moved to pass the bill out favorably. The motion passed unanimously with Rep. Cosgrove, Rep. Froerer, Rep. Gibson, Rep. Hutchings, and Rep. Tanner absent for the vote. MOTION: Rep. Stanard moved to place SB155 on the Consent Calendar. The motion passed unanimously with Rep. Cosgrove, Rep. Froerer, Rep. Gibson, Rep. Hutchings, and Rep. Tanner absent for the vote. House Revenue and Taxation Standing Committee February 18, 2014 Page 2 H.B. 77 Tax Credit for Home-schooling Parent (Rep. D. Lifferth) Rep. Lifferth explained the bill to the committee. Spoke for the bill: Hannah DeForest, citizen Elaine Augustine, citizen Connor Boyack, Libertas Institute Spoke against the bill: Deon Turley, Utah Parent Teacher Association Mark Mickelsen, Utah Education Association MOTION: Rep. -

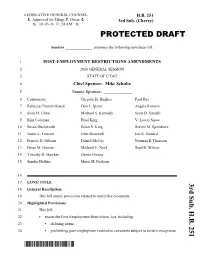

Protected Draft *Hb0251s03*

LEGISLATIVE GENERAL COUNSEL H.B. 251 6 Approved for Filing: P. Owen 6 3rd Sub. (Cherry) 6 03-03-16 11:24 AM 6 PROTECTED DRAFT Senator ______________ proposes the following substitute bill: 1 POST-EMPLOYMENT RESTRICTIONS AMENDMENTS 2 2016 GENERAL SESSION 3 STATE OF UTAH 4 Chief Sponsor: Mike Schultz 5 Senate Sponsor: ____________ 6 Cosponsors: Gregory H. Hughes Paul Ray 7 Rebecca Chavez-Houck Don L. Ipson Angela Romero 8 Scott H. Chew Michael S. Kennedy Scott D. Sandall 9 Kim Coleman Brad King V. Lowry Snow 10 Susan Duckworth Brian S. King Robert M. Spendlove 11 Justin L. Fawson John Knotwell Jon E. Stanard 12 Francis D. Gibson Daniel McCay Norman K Thurston 13 Brian M. Greene Michael E. Noel Brad R. Wilson 14 Timothy D. Hawkes Derrin Owens 15 Sandra Hollins Marie H. Poulson 16 17 LONG TITLE 3 r 18 General Description: d 19 This bill enacts provisions related to restrictive covenants. S u 20 Highlighted Provisions: b . 21 This bill: H < . 22 enacts the Post-Employment Restrictions Act, including: B . 23 C defining terms; 2 24 C prohibiting post-employment restrictive covenants subject to certain exceptions; 5 1 *HB0251S03* 3rd Sub. (Cherry) H.B. 251PROTECTED DRAFT 03-03-16 11:24 AM 25 C providing circumstances when post-employment restrictive covenants or 26 employment agreements may be executed; and 27 C addressing remedies. 28 Money Appropriated in this Bill: 29 None 30 Other Special Clauses: 31 This bill provides a special effective date. 32 Utah Code Sections Affected: 33 ENACTS: 34 34-51-101, Utah Code Annotated 1953 35 34-51-102, Utah Code Annotated 1953 36 34-51-201, Utah Code Annotated 1953 37 34-51-202, Utah Code Annotated 1953 38 34-51-203, Utah Code Annotated 1953 39 34-51-301, Utah Code Annotated 1953 40 41 Be it enacted by the Legislature of the state of Utah: 42 Section 1. -

Utah Conservation Community Legislative Update

UTAH CONSERVATION COMMUNITY LEGISLATIVE UPDATE 2019 General Legislative Session Issue #3 February 18, 2019 Welcome to the 2019 Legislative Update issue will prepare you to call, email or tweet your legislators This issue includes highlights of week two, what we can with your opinions and concerns! expect in the week ahead, and information for protecting wildlife and the environment. Please direct any questions or ACTION ALERT! comments to Steve Erickson: [email protected]. SB 52 - Secondary Water Metering Requirements passed About the Legislative Update in committee and is headed for Senate floor votes soon . Contact Senators and urge them to support this critical The Legislative Update is made possible by the Utah water saving measure and the money that goes with it. Audubon Council and contributing organizations. Each SB 144 (see bill list below) would establish a baseline for Update provides bill and budget item descriptions and measuring the impacts of the Inland Port, and generate status updates throughout the Session, as well as important data that would inform environmental studies and policy Session dates and key committees. For the most up-to-date going forward. Let Senators know this is important! information and the names and contact information for all Public and media pressure the Governor’s efforts have legislators, check the Legislature’s website at forced needed changes to HB 220, but there’s still work www.le.utah.gov. The Legislative Update focuses on to do and it’s still a bad and unnecessary bill. Keep up the calls and emails to Senators and Governor Herbert! legislative information pertaining to wildlife, sensitive and And if you still have time and energy, weigh in on a invasive species, public lands, state parks, SITLA land priority for funding (see below) – or not funding! management, energy development, renewable energy and conservation, and water issues. -

House Members Tell KUTV How They Voted on Medicaid Expansion, Mostly

House members tell KUTV how they voted on Medicaid expansion, mostly BY CHRIS JONES TUESDAY OCTOBER 20TH 2015 Link: http://kutv.com/news/local/how-members-of-the-house-voted-on-medicaid-expansion-mostly Salt Lake City — (KUTV) Last Week After three years of debate, the final negotiated plan that could bring health care to nearly 125,000 poor Utahn's failed to pass out of the Republican controlled caucus At the time, Speaker of the House Greg Hughes along with other members of the house leadership, met with the media after the closed meeting. At the time, Hughes said he and Rep. Jim Dunnigan voted for the Utah Access Plus plan. A plan that had been negotiated with top Republican leaders. Reporters criticized the house leadership for holding the closed meeting and not allowing the public to hear the debate of leaders At the time Hughes suggested that reporters ask all the members of the 63 person caucus how they voted if they wanted to know exactly who voted for what "I don't think they're going to hide it. Ask em where they're at, I think they'll tell you where they are," said Hughes So that's what we did, we emailed and called every Republican lawmaker in the caucus to find out how they voted. We do know the proposal failed overwhelmingly, one lawmaker says the vote was 57-7. Here is what we found during our research: Voted NO Daniel McCay Voted YES Rich Cunningham Jake Anderegg Johnny Anderson Kraig Powell David Lifferth Raymond Ward Brad Daw Mike Noel Earl Tanner Kay Christofferson Kay McIff Greg Hughes Jon Stanard Brian Greene Mike -

MINUTES HOUSE BUSINESS and LABOR STANDING COMMITTEE Tuesday, February 26, 2019|4:00 P.M.|445 State Capitol

MINUTES HOUSE BUSINESS AND LABOR STANDING COMMITTEE Tuesday, February 26, 2019|4:00 p.m.|445 State Capitol Members Present: Rep. Tim Quinn Rep. James A. Dunnigan, Chair Rep. Marc K. Roberts Rep. A. Cory Maloy, Vice Chair Rep. Mike Schultz Rep. Brady Brammer Rep. Casey Snider Rep. Susan Duckworth Rep. Mark A. Wheatley Rep. Craig Hall Rep. Mike Winder Rep. Brian S. King Rep. John Knotwell Staff Present: Rep. Michael K. McKell Mr. Adam J. Sweet, Policy Analyst Rep. Calvin R. Musselman Ms. An Bradshaw, Committee Secretary Note: A copy of related materials and an audio recording of the meeting can be found at www.le.utah.gov. Chair Dunnigan called the meeting to order at 4:07 p.m. 1 . H.B. 323 Impact Fees Amendments (Wilde, L.) Rep. Wilde presented the bill to the committee with the assistance of Mr. Randall Knight, Garden City Fire District. Mr. Taz Biesenger, Utah Home Builders Association, spoke in opposition to the bill. MOTION: Rep. Roberts moved to hold H.B. 323. The motion passed with a vote of 11 - 1 - 3. Yeas-11 Nays-1 Absent-3 Rep. S. Duckworth Rep. M. Winder Rep. B. Brammer Rep. J. Dunnigan Rep. T. Quinn Rep. C. Hall Rep. M. Schultz Rep. B. King Rep. J. Knotwell Rep. A. Maloy Rep. M. McKell Rep. C. Musselman Rep. M. Roberts Rep. C. Snider Rep. M. Wheatley Rep. Roberts assumed the chair. 2 . H.B. 366 Health Care Amendments (Dunnigan, J.) Rep. Dunnigan presented the bill to the committee with the assistance of Ms. Emma Chacon, Operations Directer, Division of Medicaid and Health Financing, Department of Health, and Mr. -

2013 Utah Taxpayers Association Legislative Scorecard

12 ! ! March 2013 2013 Utah Taxpayers Association Legislative Scorecard The Utah Taxpayers Association annually issues a legislative report card. The 2013 scorecard rates Utah’s 104 legislators on twenty-five key taxpayer related bills. In the House, eight bills supported by the Taxpayers Association received no dissenting votes, therefore the lowest possible score for a Utah Representative (unless there were absences) is 35%. In the Senate, thirteen bills supported by the Taxpayers Association passed without a dissenting vote meaning the lowest possible Senate score (unless there were absences) is 59%. Senate Summary House Summary The average score in the Senate is 88%. Three The average score in the House is 81%. Five senators received a perfect 100% score: Mark representatives received a perfect 100% score: Madsen, Wayne Niederhauser and Daniel Keith Grover, John Knotwell, David Lifferth, Thatcher, all Republicans. Pat Jones (73%) and Curt Oda and Jon Stanard, all Republicans. Gene Davis (70%) are the highest scoring Larry Wiley (65%) , Rebecca Chavez-Houck Democrats. (64%) and Janice Fisher (64%) are the highest scoring Democrats. No senators scored below 50%. The lowest scoring Republicans are Allen Christensen The lowest scoring Republicans are Lee Perry (77%) and Brian Shiozawa (80%). The lowest (67%) and Ronda Menlove (68%). The lowest scoring Democrats are Luz Robles (58%) and scoring Democrats are Joel Briscoe (45%), Jim Dabakis (62%). Mark Wheatley (50%) and Carol Spackman ! Moss (52%). Bills Considered for the 2013 Utah Taxpayers Association Scorecard HB 49 1st Sub (Handy) – HB 49 requires the State Board of HB 75 3rd Sub (Greene) – HB 75 establishes that professional Education to use a voted and board local levy funding balance in licensing is only appropriate where state has a compelling the prior fiscal year to increase the value of the state guarantee per health/safety interest, and licensing must be the least restrictive weighted pupil unit in the current fiscal year. -

Ann Millner 6 Cosponsors: Sandra Hollins Susan Pulsipher 7 Cheryl K

Enrolled Copy H.B. 227 1 UTAH COMPUTER SCIENCE GRANT ACT 2 2019 GENERAL SESSION 3 STATE OF UTAH 4 Chief Sponsor: John Knotwell 5 Senate Sponsor: Ann Millner 6 Cosponsors: Sandra Hollins Susan Pulsipher 7 Cheryl K. Acton Eric K. Hutchings Tim Quinn 8 Carl R. Albrecht Dan N. Johnson Adam Robertson 9 Kyle R. Andersen Marsha Judkins Angela Romero 10 Melissa G. Ballard Brian S. King Douglas V. Sagers 11 Walt Brooks Karen Kwan Mike Schultz 12 Kay J. Christofferson Bradley G. Last Travis M. Seegmiller 13 Kim F. Coleman Karianne Lisonbee Rex P. Shipp 14 Jennifer Dailey-Provost Phil Lyman Casey Snider 15 Brad M. Daw A. Cory Maloy Robert M. Spendlove 16 Susan Duckworth Kelly B. Miles Jeffrey D. Stenquist 17 Steve Eliason Jefferson Moss Andrew Stoddard 18 Joel Ferry Calvin R. Musselman Mark A. Strong 19 Francis D. Gibson Merrill F. Nelson Steve Waldrip 20 Craig Hall Derrin R. Owens Christine F. Watkins 21 Stephen G. Handy Lee B. Perry Logan Wilde 22 Suzanne Harrison Val L. Peterson Mike Winder 23 Timothy D. Hawkes Val K. Potter 24 Jon Hawkins 25 26 LONG TITLE 27 General Description: 28 This bill modifies provisions related to the Talent Ready Utah Center. H.B. 227 Enrolled Copy 29 Highlighted Provisions: 30 This bill: 31 < defines terms; 32 < modifies the responsibilities of the Talent Ready Utah Board; 33 < requires the Talent Ready Utah Board to create a computer science education master 34 plan; 35 < creates the Computer Science for Utah Grant Program; 36 < describes the requirements for the State Board of Education and the Talent Ready 37 Utah Board to administer the grant program; 38 < describes the requirements for a local education agency to apply for the grant 39 program; and 40 < describes reporting requirements of a local education agency that receives money 41 from the grant program. -

Utah Medicaid Gap Analysis February 2014

Utah Medicaid Gap Analysis February 2014 INTRODUCTION In 2010, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) called for the expansion of Medicaid coverage to certain low income adults. In a 2012 US Supreme Court ruling the Medicaid expansion became an optional element of the new law. The result was that some individuals that do not qualify for Medicaid will be left without premium subsidies as well unless individual states elect to expand their Medicaid programs. These individuals who make too much to qualify for Medicaid but too little to qualify for insurance premium subsidies have been referred to as the Medicaid “gap”. Voices for Utah Children asked Notalys, LLC, an economic research and data intelligence firm, to estimate the number of individuals in the Medicaid gap in each legislative district in Utah. Notalys utilized population data from the American Community Survey (ACS) 5-year estimates compiled by the U.S. Census Bureau to arrive at these estimations. While several intricacies of the Medicaid eligibility and ACA subsidy rules cannot be exactly represented with existing and available data sources, Notalys has taken extreme care to represent the statistical ranges for each estimate and outline the possible limitations of this study. Main Findings The results of this analysis are a district by district estimate for the total number of people who are likely to be affected by the Medicaid gap if Medicaid is not expanded in the state of Utah. These numbers are presented in terms of the total count of individuals in the district who fall into the gap and in terms of the percentage of all adults 18-64 within the district who fall into the gap.