Draft Plan Strategy Response Form

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Written Answers to Questions Official Report (Hansard)

Written Answers to Questions Official Report (Hansard) Friday 4 July 2014 Volume 96, No WA4 This publication contains the written answers to questions tabled by Members. The content of the responses is as received at the time from the relevant Minister or representative of the Assembly Commission and has not been subject to the official reporting process or changed in any way. Contents Written Answers to Questions Office of the First Minister and deputy First Minister ............................................................... WA 379 Department of Agriculture and Rural Development .................................................................. WA 385 Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure ................................................................................ WA 388 Department of Education ...................................................................................................... WA 389 Department for Employment and Learning .............................................................................. WA 431 Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment .................................................................... WA 436 Department of the Environment ............................................................................................. WA 447 Department of Finance and Personnel ................................................................................... WA 465 Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety ......................................................... WA 473 Department -

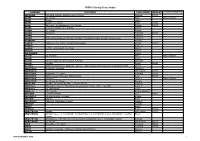

Church Records Available As Digital Copies in PRONI Church of Ireland Records (CR1)

Church Records Available as Digital Copies in PRONI Church of Ireland Records (CR1) Christ Church, Derriaghy, Lisburn, Co. Antrim (CR1/1) Parish: Derryaghy, Co. Antrim Burials 1873-1913 Magheracross Parish Church, Ballinamallard, Co Fermanagh (CR1/20) Parish: Mageracross, Co. Fermanagh Combined Baptisms, Marriages & Burials 1800-1839 Marriages 1845-1935 & 1937-1967 (1936 not received, records from 1908-1967 are closed) Knockbreda Parish Church, Belfast, Co. Down (CR1/24) Parish: Knockbreda, Co. Down Graveyard Register c.1763-2014 Craigs Parish Church, Cullybackey, Co. Antrim (CR1/55) Parish: Craigs, Co. Antrim Baptisms 1839-1925 (records from 1918-1925 are closed) Marriages 1841-1925 Burials 1841-1944 Vestry Minutes 1874-1904 Register of Vestrymen 1870-1910 St Matthew’s Parish Church, Shankill, Belfast, Co. Antrim (CR1/65) Parish: Belfast Baptisms 1893-1905 Marriages 1897-1916 Burials 1887-1917 Vestry Minutes 1858-1900 Confirmation Register 1893-1930 (closed) St. Columb’s Cathedral, Londonderry (CR1/113) Parish: Templemore, Co. Londonderry Baptisms 1642 – 1983 (records from 1905 – 1983 are closed) Marriages** 1680 – 1830, 1843 – 1904 Burials** 1680 – 1955 (records from 1874 – 1955 are closed) Vestry Books 1741 – 1793 Vestry Minutes 1823 – 1935 **Please note for Marriages (1680-1826) & Burials (1680-1829), consult combined Baptism, Marriage & Burial Registers in CR1/113/1 Derryloran Parish, Co. Tyrone (CR1/114) Parish: Derryloran, Co. Tyrone Baptisms 1797 – 1995 (records from 1913 – 1995 are closed) Marriages** 1797 – 2000 (records from 1930 – 2000 are closed) Burials** 1798 – 1878 ** Please note for Marriages (1797-1832) & Burials (1798-1855), consult combined Baptism, Marriage & Burial Registers in CR1/114/1 St. Anne’s Cathedral, Belfast, Co. -

Young People / Youth Groups

ORGANISATION CONTACT PERSON ADDRESS POSTCODE TEL. NO A Aghalee & District Development Larry Donaghy c/o 10 Old Church Lane Aghalee BT67 0EB 92652765 Association Aghalee Village Hall Management Pauline Buller 6 Lurgan Road Aghalee BT67 0DD 38323622 Committee AMH ACCEPT Nadia MacLynn Dunellen House Dunmurry Industrial Estate Lisburn BT17 9HU 90629759 An Gleann Ban Residents Seamus McGuiness 52 White Glen Lagmore Dunmurry BT17 0XN 90627657 Association Areema Residents Association Amanda Hanna 50c Alina Gardens Dunmurry Belfast BT17 0QJ 90942881 ASCERT Gary McMichael 23 Bridge Street Lisburn BT28 1XZ 92604422 Atlas Womens Centre Stephen Reid 79 / 81 Sloan Street Lisburn Co. Antrim BT27 5AG 92605806 B Ballinderrry Community Association Stephen Cotton c/o 19 Ashcroft Way Ballinderry Lower Lisburn BT28 2AY 92652632 Brook Children Together Mary Mullan 2 Mulberry Park Twinbrook Belfast BT17 0DJ 90291333 Brookmount Cultural Margaret Tolerton 2 Killowen Mews Glenavy Road Lisburn BT28 3AR 92677872 & Educational Group Bytes Project Clem & Brenda c/o Sally Garden Community Centre Sally Garden Lane Poleglass BT17 0PB 90309127 C Care for the Family Jean Gibson 3 Wallace Avenue Lisburn BT27 4AA 92628050 Cargycroy Community Group Aubrey Campbell 90382646 Church of the Nativity Guides Catherine Burns c/o 17 Old Colin Poleglass Belfast BT17 0AX Cloona Oasis Centre Geraldine Cunningham Cloona House 30 Colin Road Poleglass BT17 0LG 90624923 Colin Community Counselling Anne McLarnon c/o Colin Family Centre Pembrooke Loop Road Dunmurry BT17 0PH 90604347 Project -

Lagan Valley

Parliamentary Polling Scheme Review Draft 2019 CONSTITUENCY: LAGAN VALLEY BALLINDERRY PARISH CHURCH HALL, 7A NORTH STREET, BALLINDERRY, BT28 2ER BALLOT BOX 1/LVY TOTAL ELECTORATE 983 WARD STREET POSTCODE 1902 AGHALEE ROAD, AGHAGALLON, CRAIGAVON BT67 0AS 1902 BALLINDERRY ROAD, AGHALEE, CRAIGAVON BT67 0DY 1902 BALLYCAIRN ROAD, AGHALEE, CRAIGAVON BT67 0DR 1902 BRANKINSTOWN ROAD, AGHALEE, CRAIGAVON BT67 0DE 1902 BEECHFIELD LODGE, AGHALEE, CRAIGAVON BT67 0GA 1902 BEECHFIELD MANOR, AGHALEE, CRAIGAVON BT67 0GB 1902 BROADWATER COTTAGES, AGHALEE, CRAIGAVON BT67 0XA 1902 BROADWATER MEWS, AGHALEE, CRAIGAVON BT67 0FR 1902 BROADWATER PARK, AGHALEE, CRAIGAVON BT67 0EW 1902 CANAL MEWS, AGHALEE, CRAIGAVON BT67 0FW 1902 CHAPEL ROAD, AGHALEE, CRAIGAVON BT67 0EA 1902 CORONATION GARDENS, AGHALEE, CRAIGAVON BT67 0EU 1902 GROVELEA, AGHALEE, CRAIGAVON BT67 0DX 1902 HELENS DRIVE, AGHALEE, CRAIGAVON BT67 0HE 1902 STANLEY COURT, AGHALEE, CRAIGAVON BT67 0WW 1902 HELENS PARK, AGHALEE, CRAIGAVON BT67 0EN 1902 HOLLY BROOK, AGHALEE, CRAIGAVON BT67 0GZ 1902 LIME KILN LANE, AGHALEE, CRAIGAVON BT67 0EZ 1902 LOCKVALE MANOR, AGHALEE, CRAIGAVON BT67 0LU 1902 MEADOWFIELD COURT, AGHALEE, CRAIGAVON BT67 0EL 1902 THE OLD ORCHARD, AGHALEE, CRAIGAVON BT67 0EZ 1902 LURGAN ROAD, AGHALEE, CRAIGAVON BT67 0DD 1902 LURGAN ROAD, AGHALEE, CRAIGAVON BT67 0FX 1902 LURGAN ROAD, AGHALEE, CRAIGAVON BT67 0DD 1902 MORNINGTON RISE, AGHALEE, CRAIGAVON BT67 0FN 1902 OLD CHURCH LANE, AGHALEE, CRAIGAVON BT67 0EB 1902 OLD CHURCH LANE, AGHALEE, CRAIGAVON BT67 0EY 1902 FRIARS GLEN, 5 OLD CHURCH LANE, -

Memoirs of the Fultons of Lisburn

LilSBU^N R-.I-J1. .Lr i> ^ -1 n National Library of Scotland *B000407002* Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/memoirsoffultlisOOhope MEMOIRS OF THE FULTONS OF LISBURN MEMOIRS OF THE FULTONS OF LISBURN COMPILED BY SIR THEODORE C. HOPE, K.C.S.I. 5 CLE. BOMBAY CIVIL SERVICE (RETIRED) PRINTED FOR PRIVATE CIRCULATION '9°3 PREFACE In 1894 I was called upon by some members of the Fulton family, to which my mother and my wife belonged, for information as to their pedigree, and it gradually came about that, with their general consent and at the desire of Mr. Ashworth P. Burke, I revised the proofs of the account given in Burke's Colonial Gentry, published in 1895, ar) d eventually compiled the fuller and more accurate notice in Burke's Landed Gentry of Great Britain and Ireland, edition of 1898, Vol. II., Ireland, pp. 156-58. In the researches thus necessitated, a large number of incidents, dates, alliances, etc., came to light which were inadmissible into the formal Pedigree which was proved and recorded by the Heralds' College in the last-mentioned year, and could not be given within the limits (very liberal though they were) prescribed by Mr. Burke. To preserve, without intolerable prolixity, all available information, is the object of the following pages. The materials for this task originally at my disposal, in addition to the first notice in the Landed Gentry of 1862, consisted only of (1) a letter and some brief memoranda in the hand- writing of my uncle, John Williamson Fulton, with corrections thereon by his sister, Anne Hope (my mother), and a letter of hers to me, all falling within the period 1861-63, and (2) a long detailed account up to the then date which he dictated to me at Braidujle House in September 1872, with copies of McVeigh, Camac, Casement and Robinson pedigrees, which he then allowed me to make. -

Register of Employers 2021

REGISTER OF EMPLOYERS A Register of Concerns in which people are employed In accordance with Article 47 of the Fair Employment and Treatment (Northern Ireland) Order 1998 The Equality Commission for Northern Ireland Equality House 7-9 Shaftesbury Square Belfast BT2 7DP Tel: (02890) 500 600 E-mail: [email protected] August 2021 _______________________________________REGISTRATION The Register Under Article 47 of the Fair Employment and Treatment (Northern Ireland) Order 1998 the Commission has a duty to keep a Register of those concerns employing more than 10 people in Northern Ireland and to make the information contained in the Register available for inspection by members of the public. The Register is available for use by the public in the Commission’s office. Under the legislation, public authorities as specified by the Office of the First Minister and the Deputy First Minister are automatically treated as registered with the Commission. All other employers have a duty to register if they have more than 10 employees working 16 hours or more per week. Employers who meet the conditions for registration are given one month in which to apply for registration. This month begins from the end of the week in which the concern employed more than 10 employees in Northern Ireland. It is a criminal offence for such an employer not to apply for registration within this period. Persons who become employers in relation to a registered concern are also under a legal duty to apply to have their name and address entered on the Register within one month of becoming such an employer. -

Co. Leitrim & Mohill A3175 ABBOTT A2981 ABERNETHY Stewartstown

North of Ireland Family History Society - List of Ancestor Charts SURNAME AREA MEM. NO. ABBOTT Shane (Meath), Co. Leitrim & Mohill A3175 ABBOTT A2981 ABERNETHY Stewartstown, Arboe & Coalisland A3175 ABRAHAM London A2531 ABRAHAM Pettigo, Co. Donegal & Paisley A2145 ACHESON County Fermanagh B1804 ADAIR Gransha (Co. Down) & Ontario A2675 ADAMS Ballymena & Cloughwater B2202 ADAMS Coleraine B1435 ADAMS Rathkeel, Ballynalaird, Carnstroan, Ballyligpatrick B1751 ADAMS Carnmoney A2979 ADAMSON Northumberland A2793 ADAMSON Montiaghs A3930 AIKEN A3187 AKENHEAD British Columbia, Canada & Northumberland A2693 ALDINGTEN Moreton Bagot A3314 ALEXANDER Co. Tyrone A2244 ALEXANDER Malta B2239 ALEXANDER County Donegal B2324 ALEXANDER A3888 ALFORD Dublin South & Drogheda B2258 ALLAN Greenock A1720 ALLAN Alexandria A3561 ALLANDER County Londonderry B2324 ALLEN Belfast A0684 ALLEN Co. Down A3162 ALLEN Ballymena B2192 ALLEN County Wicklow & Carlisle, England B0817 ALLEN Crevolea, Macosquin A0781 ALLEN Comber B2123 ALLISON A3135 ALLSOPP Abersychan & Monmouthshire, Wales A2558 ALLWOOD Birmingham B2281 ALTHOFER New South Wales & Denmark A3422 ANDERSON A3291 ANDERSON B0979 ANDERSON Greenock A1720 ANDERSON Sweden A3700 ANDERSON Greenock, Scotland A3999 ANGUS A2693 ANGUS A3476 ANGUS Ayrshire & Lanarkshire A3929 APPELBY Hull B1939 APPLEBY Cornwall B0412 ARBUCKLE A1459 ARCHER A0431 ARCHIBALD Northern Ireland & Canada A3876 ARD Armagh A1579 ARLOW Co. Tyrone & Co. Tipperary A2872 ARMOUR Co. Limerick A1747 ARMOUR Paisley, Scotland B2366 ARMSTRONG Belfast & Glasgow A0582 ARMSTRONG Omagh A0696 May 2016 HMRC Charity No. XR22524 www.nifhs.org North of Ireland Family History Society - List of Ancestor Charts ARMSTRONG Belfast A1081 ARMSTRONG New Kilpatrick A1396 ARMSTRONG Aghalurcher & Colmon Island B0104 ARMSTRONG B0552 ARMSTRONG B0714 ARMSTRONG Co. Monaghan A1586 ARMSTRONG B1473 ARMSTRONG Magheragall, Lisburn B2210 ARMSTRONG A3275 ARMSTRONG Cumbria A3535 ARNOLD New York & Ontario A3434 ARNOLD Yorkshire B1939 ARTHUR Kells, Co. -

The Belfast Gazette Published Bp Flutboritp

Number 2154 361 The Belfast Gazette Published bp flutboritp Registered as a newspaper FRIDAY, 5th OCTOBER, 1962 - . Privy Council Office, Samuel Ernest Browne, Esq., M.B., B.Ch., 5th October, 1962. 23, Glenburn Park, Belfast, 14. OIL IN NAVIGABLE WATERS ACT, 1955 Hugh Gray Campbell, Esq., M.P.S., NOTICE is hereby given that Her Majesty in Council was pleased, on the 2nd October, 1962, to Wandeen, approve an Order in Council under the above named Ballymoney, Act 'entitled "The Oil in Navigable Waters (Exten- Co. Antrim, sion of Convention) (Netherlands Antilles) Order 1962." (S.I. 1962/2189). David Addison Dorman, Esq., - Copies of the said Order when published may be Killeaton House, purchased directly from H.M. Stationery Office at Derriaghy, 80 Chichester Street, Belfast, or York House, Kings- Dunmurry, way, London, W.C.2; or through any bookseller. Co. Antrim. Victor Alexander Hewitt, Esq., L.D.S., 20 Malone Road, MINISTRY OF COMMERCE FOR NORTHERN Belfast, 9. IRELAND Herbert Hooton Mitchell, Esq., TRANSPORT ACT (NORTHERN IRELAND), 1948 F.B.O.A., F.S.M.C., TRANSPORT TRIBUNAL 18 Callender Street, Belfast, 1. His Excellency the Governor of Northern Ireland has been pleased by Warrant under his hand dated Robert Ferguson McKeown, Esq., September, 1962, to appoint, pursuant to Section 43 M.B., B.A.O., B.Ch., D.P.H., of) the Transport Act (Northern Ireland), 1948, 10 Holmview Terrace, Robert George Manson, Esquire, C.I.E., M.InstT., Campsie, and Hugh Chesley Boyd, Esquire, F.C.A., to be Members of the Transport Tribunal for Northern Omagh, Ireland until 31st December, 1963. -

Focus on Readers Pages 4-5

Focus on Readers pages 4-5 The magazine for the Diocese of Connor Autumn 2018 222 Connor Connections Autumn 2018 Bishop’s MessageSection / News A refreshing and creative time Autumn 2018 I am very grateful to all who helped during journey and rediscovering the amazing my sabbatical, especially Team Connor and grace made known to us in Jesus. In the archdeacons. There was certainly a reading the gospels in depth again and Contents warm welcome when I returned. penning my reflections on Jesus, my heart and spirit were refreshed and renewed. I had a very refreshing and creative time, New Sunday School resource 6 writing, travelling, praying and having some May we all know the presence of the risen special time with my family. I will be sharing Jesus journeying with us as we seek to GB NI honour for Alison 7 some of my thoughts at the evening incarnate his grace and presence in our session of Diocesan Synod and at next local communities. Holy Land reflections 8-9 year’s Lenten Seminars. Grace and peace, Youth news 10-11 One of the joys of being on sabbatical was having time to reflect on my own faith Organ scholars rewarded 12 A new life in Whitehead 13 St Paul’s GB in Uganda 14 Institution in Larne Preserving Derriaghy’s spire 15 Young adults’ mission 16-17 Spiritual Direction support 18 New Diocesan MU President 21 All Saints’ in South Africa 23 Cover photo: The stunning Virginia Creeper which adorns the tower leading to the spire at Christ Church, Derriaghy. -

NIFHS Family Trees Index

NIFHS Family Trees Index SURNAME LOCATIONS FILED UNDER MEM. NO OTHER INFORMATION ABRAHAM Derryadd, Lurgan; Aughacommon, Lurgan Simpson A1073 ADAIR Co. Antrim Adair Name Studies ADAIR Belfast Lowry ADAIR Bangor, Co. Down Robb A2304 ADAIR Donegore & Loughanmore, Co. Antrim Rolston B1072 ADAMI Germany, Manchester, Belfast Adami ADAMS Co. Cavan Adams ADAMS Kircubbin Pritchard B0069 ADAMS Staveley ADAMS Maternal Grandparents Woodrow Wilson, President of USA; Ireland; Pennsylvania Wilson 1 ADAMSON Maxwell AGNEW Ballymena, Co. Antrim; Craighead, Glasgow McCall A1168 AGNEW Staveley AGNEW Belfast; Groomsport, Co. Down Morris AICKEN O'Hara ALEXANDER Magee ALLEN Co. Armagh Allen Name Studies ALLEN Corry ALLEN Victoria, Australia; Queensland, Australia Donaghy ALLEN Comber Patton B2047 ALLEN 2 Scotland; Ballyfrench, Inishargie, Dunover, Nuns Quarter, Portaferry all County Down; USA Allen 2 ANDERSON Mealough; Drumalig Davison 2 ANDERSON MacCulloch A1316 ANDERSON Holywood, Co. Down Pritchard B0069 ANDERSON Ballymacreely; Killyleagh; Ballyministra Reid B0124 ANDERSON Carryduff Sloan 2 Name Studies ANDERSON Derryboye, Co Down Savage ANDREWS Comber, Co. Down; Quebec, Canada; Belfast Andrews ANKETELL Shaftesbury, Dorset; Monaghan; Stewartstown; Tyrone; USA; Australia; Anketell ANKETELL Co. Monaghan Corry ANNE??? Cheltenham Rowan-Hamilton APPLEBY Cornwall, Belfast Carr B0413 ARCHBOLD Dumbartonshire, Scotland Bryans ARCHER Keady? Bean ARCHIBALD Libberton, Quothquan, Lanark Haddow ARDAGH Cassidy ARDRY Bigger ARMOUR Reid B0124 ARMSTRONG Omagh MacCulloch A1316 ARMSTRONG Aghadrumsee, Co. Fermanagh; Newtownbutler, Co. Fermanagh; Clones, Monaghan; Coventry; Steen Belfast ARMSTRONG Annaghmore, Cloncarn, Drummusky and Clonshannagh, all Co. Fermanagh; Belfast Bennett ARMSTRONG Co Tyrone; McCaughey A4282 AULD Greyabbey, Co. Down Pritchard B0069 BAIRD Pritchard B0069 BAIRD Strabane; Australia - Melbourne and New South Wales Sproule BALCH O'Hara NIFHS MARCH 2018 1 NIFHS Family Trees Index SURNAME LOCATIONS FILED UNDER MEM. -

Written Answers to Questions

Official Report (Hansard) Written Answers to Questions Friday 5 March 2010 Volume 49, No WA1 This publication contains the written answers to questions tabled by Members. The content of the responses is as received at the time from the relevant Minister or representative of the Assembly Commission and has not been subject to the official reporting process or changed in any way. Contents Written Answers to Questions Office of the First Minister and deputy First Minister .........................................................................1 Department of Agriculture and Rural Development ..........................................................................65 Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure ........................................................................................69 Department of Education ..............................................................................................................82 Department for Employment and Learning ....................................................................................114 Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment ..........................................................................116 Department of the Environment ...................................................................................................125 Department of Finance and Personnel .........................................................................................153 Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety ...............................................................157 -

Derriaghy Rector Installed As New Canon of Rashark

CONNORDIOCESE.ORG.UK Derriaghy rector installed as new Canon of Rashark Report and photographs by John Kelly The rector of Derriaghy Parish, the Rev Canon John Budd, was installed as Prebendary of Rasharkin in Christ Church Cathedral, Lisburn on Monday June 2. The new canon was installed by the Dean of Connor, The Very Rev John Bond. Originally from Essex, Canon Budd is a graduate of Queen’s University. After serving his first curacy in Ballymena and a further curacy in Jordanstown with Monkstown, he was appointed rector of Craigs with Dunaghy & Killagan and has been rector of Derriaghy with Colin since 1997. Married to Carla, Canon Budd has three grown up children Peter, Harriet and Matthew. The Archdeacon of Connor, The Ven Dr Stephen McBride, presented the new Canon to Dean Bond to be installed as Prebendary of Rasharkin in the Chapter of St Saviour in Christ Church Cathedral. The address was given by the Rev Canon George Irwin, Rector of Ballymacash, who has known Canon Budd since College days. He paid tribute to the new Canon’s many fine qualities and said that the appointment by the Bishop was recognition of Canon Budd’s contribution to the diocese. Also taking part in the service were Canon Sam Wright, Rector of Lisburn Cathedral, Chancellor Stuart Generated from http://connordiocese.org.uk/?do=news&newsid=1123 Date: 07.06.2011 at 12:06:20PM An RTNetworks site CONNORDIOCESE.ORG.UK Derriaghy rector installed as new Canon of Rashark Lloyd, Canon Percy Walker, the Rev Simon Genoe, Cathedral Curate, and the Bishop of Connor.