Pinellas Past, Present, and Future [1992-2012]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FRIDAY, APRIL 18, 2014 Vs. NEW YORK YANKEES LH Erik Bedard (0-0, 0.00) Vs

FRIDAY, APRIL 18, 2014 vs. NEW YORK YANKEES LH Erik Bedard (0-0, 0.00) vs. RH Hiroki Kuroda (2-1, 3.86) First Pitch: 7:10 p.m. | Location: Tropicana Field, St. Petersburg, Fla. | TV: Sun Sports | Radio: WDAE 620 AM, WGES 680 AM (Spanish) Game No.: 17 (7-9) | Home Game No.: 9 (3-5) | All-Time Game No.: 2,607 (1,202-1,404) | All-Time Home Game No.: 1,303 (670-632) BEN & JULES BOOK SIGNING—Tomorrow from 11 a.m.–1 p.m., 2B/OF EASTERN SUPREMACY—Since 2011, BEST RECORD WITHIN Ben Zobrist and his wife, singer Julianna Zobrist, will hold a public book the Rays own the best record within AL EAST, SINCE 2011 signing at the Tropicana Field Team Store for their new autobiography, Dou- the AL East at 128-99 (.564)…during Tampa Bay 128-99 .564 ble Play…the book will be available there in the team store for $24.99. this span their four AL East opponents New York 124-107 .537 (BOS, NYY, BAL, TOR) all rank among Baltimore 113-118 .489 RAY MATTER—The Rays have lost 4 straight games and been outscored the majors’ top 9 in runs scored—yet the Boston 111-116 .489 Toronto 97-133 .422 32-7 during the skid…this is their longest streak since losing 5 straight, Aug Rays have recorded a 3.47 ERA, more 29–Sep 2, 2013…the Rays have slipped into a tie with Boston for fourth place than a run better than the rest of base- LOWEST ERA WITHIN in the AL East, 3.0 GB of first-place New York…at 7-9, the Rays have a losing ball (4.48) vs. -

Matt Silverman President

RAYS ORGANIZATION } FRONT OFFICE MATT SILVERMAN PRESIDENT Commissioner Bud Selig being realized. In 2010, the Rays local television had this to say last fall when ratings rose to fifth highest in all of baseball. And asked about the Tampa Bay in 2011, the FOX network has tabbed the Rays Rays after the team had for eight national or regional telecasts. clinched its second Ameri- To build this regional presence, Silverman de- can League East championship: “It is a great cided early on to do things a little differently. In franchise; they have done a marvelous job. They 2007 and 2008, he relocated a series of regular- have run it beautifully.” season games to the Disney Sports Complex That praise, echoed by many others in Major in Orlando, expanding the team’s reach across League Baseball, is due in no small part to Rays Central Florida. In 2009, the team opened its first President Matt Silverman. spring training camp at Charlotte Sports Park, One of the youngest team presidents in the a state-of-the-art facility that has drawn glow- history of the game, 34-year-old Matt Silverman ing reviews and given the Rays a year-round is in his sixth year of overseeing the day-to-day presence in the southern part of its region along operations of the Rays, widely recognized as Florida’s Gulf Coast. In their first two seasons in one of professional sports’ best success stories. Charlotte County, the Rays have played before Under his direction, the revitalized Rays con- 90 percent capacity in 31 home games. -

THURSDAY, APRIL 17, 2014 Vs. NEW YORK YANKEES LH David Price (2-0, 2.91) Vs

THURSDAY, APRIL 17, 2014 vs. NEW YORK YANKEES LH David Price (2-0, 2.91) vs. LH CC Sabathia (1-2, 6.63) First Pitch: 7:10 p.m. | Location: Tropicana Field, St. Petersburg, Fla. | TV: Sun Sports | Radio: WDAE 620 AM, WGES 680 AM (Spanish) Game No.: 16 (7-8) | Home Game No.: 8 (3-4) | All-Time Game No.: 2,606 (1,202-1,403) | All-Time Home Game No.: 1,302 (670-631) THOUGHTS & PRAYERS—Yesterday Rays Senior Baseball Advisor Don EASTERN SUPREMACY—Since 2011, BEST RECORD WITHIN Zimmer underwent more than six hours of surgery to repair a leaky valve the Rays own the best record within AL EAST, SINCE 2011 in his heart…he is resting comfortably and is expected to remain in the the AL East at 128-98 (.566)…during Tampa Bay 128-98 .566 hospital a few days while he recovers…Zim, now in his 66th season of pro- this span their four AL East opponents New York 123-107 .535 fessional baseball, has worn 14 different major league uniforms as a player, (BOS, NYY, BAL, TOR) all rank among Baltimore 113-118 .489 manager and coach (see page 42 of the 2014 Rays Media Guide) but has the majors’ top 9 in runs scored—yet the Boston 111-116 .489 Toronto 97-133 .422 spent the most time in a Rays uniform (11 seasons). Rays have recorded a 3.44 ERA, more Ê Zim underwent surgery the same day the Rays wore No. 42 in honor of than a run better than the rest of base- LOWEST ERA WITHIN Jackie Robinson—his teammate on the 1954-56 Brooklyn Dodgers. -

Palatka Man Dies Following 11Th St. Shooting Landfill Task Force

Sunny A CENTURY OF LIFE 0% rain chance | Charlie Bryant of Florahome is turning 100 on Monday. APPLAUSE, Inside 91 72 For details, see 2A www.mypdn.com PALATKA DAILY NEWS THURSDAY, JUNE 5, 2014 $1 Palatka TOP SCHOLAR HAS ROOTS IN AGRICULTURE Landfi ll man dies task force following hears 11th St. details of shooting clean-up Police have County faces no suspects or millions in future witnesses in early remediation costs, Wednesday homicide they’re told BY PETE SKIBA BY BRANDON D. OLIVER Palatka Daily News Palatka Daily News Multiple gunshots split CHRIS DEVITTO / Palatka Daily News The Putnam County Solid the night and left one man Ashley Adams of Palatka High School was recognized as Putnam County’s top scholar with the Robert W. Webb Waste Task Force discussed bleeding out on a northside Award of Excellence on May 14 at the annual Top 50 Scholars reception sponsored by the Daily News. the local landfill remediation porch Wednesday, accord- during a meeting on Tuesday. ing to a Palatka Police The topic of mining and lin- Department report. ing nearly 100 acres of the A Putnam County Fire ‘She is going to do what it takes to win’ landfill so as to repair the ben- and EMS ambulance took zene groundwater contamina- 40-year-old Iseley Crowley, tion was brought into the mix of Palatka, from 606 N. 11th BY JENNIFER THOMAS Putnam County Top Scholar. She Adams, 17. Ashley Adams said that as the task force considered St. to Putnam Community Palatka Daily News correspondent was handed the Robert W. -

Rays Trade Evan Longoria to Giants St

For Immediate Release December 20, 2017 RAYS TRADE EVAN LONGORIA TO GIANTS ST. PETERSBURG, Fla.—The Tampa Bay Rays have traded third baseman Evan Longoria and cash considerations to the San Francisco Giants in exchange for outfielderDenard Span, infielderChristian Arroyo, minor league left-handed pitcher Matt Krook and minor league right-handed pitcher Stephen Woods Jr. Longoria, 32, departs as the longest-tenured player in franchise history, after spending nearly 10 seasons in a Rays uniform. He is the club’s all-time leader with 1,435 games played, 261 home runs, 892 runs batted in, 338 doubles, 618 extra-base hits, 780 runs scored, 569 walks and 2,630 total bases. Of the 30 postseason games in Rays history, all 30 have featured Longoria in the starting lineup at third base. “Evan is our greatest Ray. For a decade, he’s been at the center of all of our successes, and it’s a very emotional parting for us all,” said Principal Owner Stuart Sternberg. “I speak for our entire organization in wishing Evan and his wonderful family our absolute best.” Longoria collected many awards over the course of his Rays career. In 2008, he was unanimously voted as the American League Rookie of the Year by the Baseball Writers’ Association of America, becoming the first Ray to win a national BBWAA award. He was selected as an American League All-Star in each of his first three seasons (2008, 2009, 2010). In 2009, he won the Silver Slugger Award for AL third basemen. In November, Longoria earned his club-record third Rawlings AL Gold Glove Award, after winning the honor in 2009 and 2010. -

Mayor Don Jones Can You Canoe?

MAR/APR 2016 St. Petersburg, FL Est. September 2004 Happy 85th Anniversary Junior League of St Petersburg Virginia Littrell ow would you celebrate an 85th anniversary? Have a party, of course! And no one throws a party better than the Junior League! H Lest you think this is a Junior League of pearls, white gloves, and sterling tea service – think again. Since 1931, the Junior League of St. Petersburg (JLSP ) has been a driving force in improving our community for families and especially children. Members of the Junior League are accomplished collaborators who build coalitions, identify community needs, and develop effective and responsive programs to serve those needs. For 85 years, members of the Junior League have focused their energies on school readiness and literacy, improved health care and nutrition, Dr. George Stovall support for the arts, and advocacy for environmental responsibility through effective Can You Canoe? action and trained leadership. Linda Dobbs Collectively, the Junior League has donated more than $3 FROM OCEAN, TO GULF, TO BAYOU, AND SWAMPS AND million and 7 million hours of RIVERS, TOO... GEORGE CAN DO, CAN YOU? volunteer support to programs nell Isle resident, Dr. George Stovall, can canoe. In fact, and agencies in St. Petersburg he is locally famous for his adventures, large and medium – and Pinellas County. Sno small ones. Key Largo to Bimini; from Fort Clinch on So, it makes sense that when Fernandina Beach, up the St. Mary’s into the Okefenokee Swamp, into the Suwanee River, and down to Cedar Key; members of the League set out coastlines in Florida to Georgia to both Carolinas; George has to create a year-long celebration done it, alone and with companions. -

American Jews and America's Game

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and Chapters University of Nebraska Press Spring 2013 American Jews and America's Game Larry Ruttman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/unpresssamples Ruttman, Larry, "American Jews and America's Game" (2013). University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and Chapters. 172. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/unpresssamples/172 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Nebraska Press at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 3 4 American Jews & America’s Game 7 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 Buy the Book The Elysian Fields, Hoboken, New Jersey, the site of the first organized baseball game (1846). Courtesy of the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown NY. Buy the Book 3 4 7 American Jews & America’s Voices of a Growing Game Legacy in Baseball LARRY RUTTMAN Foreword by Bud Selig Introduction by Martin 3 Abramowitz 3 3 3 3 3 3 University of Nebraska Press 3 Lincoln and London 3 Buy the Book © 2013 by Lawrence A. Ruttman All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ruttman, Larry. American Jews and America’s game: voices of a growing legacy in baseball / Larry Ruttman; foreword by Bud Selig; introduction by Martin Abramowitz. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Major League Baseball (Appendix 1)

Sports Facility Reports, Volume 7, Appendix 1 Major League Baseball Team: Arizona Diamondbacks Principal Owner: Jeffrey Royer, Dale Jensen, Mike Chipman, Ken Kendrick, Jeff Moorad Year Established: 1998 Team Website Most Recent Purchase Price ($/Mil): $130 (1995) Current Value ($/Mil): $305 Percent Change From Last Year: +7% Stadium: Chase Field Date Built: 1998 Facility Cost (millions): $355 Percentage of Stadium Publicly Financed: 71% Facility Financing: The Maricopa County Stadium District provided $238 M for the construction through a .25% increase in the county sales tax from April 1995 to November 30, 1997. In addition, the Stadium District issued $15 M in bonds that is being paid off with stadium-generated revenue. The remainder was paid through private financing; including a naming rights deal worth $66 M over 30 years. Facility Website UPDATE: Between the 2005 and 2006 seasons, the Diamondbacks added a new $3.3 M LED display board to Chase Field. The board is the largest LED board in Major League Baseball. The Diamondbacks also upgraded the Chase Field sound system and added two high-end, field level suites. The changes were paid for by a renewal and refurbishment account, which was created when the ballpark was built. Maricopa County and the Diamondbacks both contribute to the account. NAMING RIGHTS: On June 5, 1995, the Arizona Diamondbacks entered into a $66 M naming-rights agreement with Bank One that extends over 30 years, expiring in 2028, and averaging a yearly payout of $2.2 M. In January 2004, Bank One Corporation and J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. merged and announced they were fazing out the Bank One brand name. -

Edward Ringwald PO Box 20174 St Petersburg FL 33742-0174 (727) 576-3450 Email [email protected]

Edward Ringwald PO Box 20174 St Petersburg FL 33742-0174 (727) 576-3450 Email [email protected] 4 October 2010 Revised 28 May 2011 Mr. Toddy Hardy, Event Manager Tampa Bay Rays One Tropicana Drive St. Petersburg, FL 33705 Dear Mr. Hardy: Re: Treatment of fans by Rays staff during Rays games at Tropicana Field I have some questions for you related to how fans are treated when they attend Rays games at Tropicana Field, especially treatment by your Rays security officers. I have attended so many Rays games over the years including the championship games in 2008 where we won the American League East division title and we had a chance to play in the World Series, only to lose to the Philadelphia Phillies. As you probably know already, we won the American League East division title last year and we went back to the playoffs in the hope that we go to the World Series for a second attempt, only to have this attempt stifled by the Texas Rangers. Despite a great 2009 and 2010 season for the Rays, attendance numbers have not been promising. The only time you have sold out games is when the New York Yankees as well as the Boston Red Sox are in town, not to mention the 25,000 tickets that were given away at the Rays’ last home game of the 2010 season against the Baltimore Orioles after Evan Longoria went public about the low attendance numbers at another game the day before. I can understand, however, that weekday attendance is low due to the fact that people have to work the next day and that a majority of Rays fans live in Tampa. -

What Contributing Factors Play the Most Significant Roles in Increasing the Winning Percentage of a Major League Baseball Team?

Cost of Winning: What contributing factors play the most significant roles in increasing the winning percentage of a major league baseball team? The Honors Program Senior Capstone Project Student’s Name: Patrick Tartaro Faculty Sponsor: Betty Yobaccio April 2012 Table of Contents Abstract ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 1 Literary Review ......................................................................................................................... 3 Methodolgy ............................................................................................................................. 10 Results ..................................................................................................................................... 13 Discussion…………………………………………………………………………………….21 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………28 References ............................................................................................................................... 30 Cost of Winning: What contributing factors play the most significant roles in increasing the winning percentage of a major league baseball team? Patrick Tartaro ABSTRACT Over the past decade, discussions of competition disparity in Major League Baseball have been brought to the forefront of many debates regarding the sport. The belief -

Citrus County Chronicle to Dose Series of Shots

Project1:Layout 1 6/10/2014 1:13 PM Page 1 Tennis: Lecanto girls have a perfect day at districts /B1 TUESDAY TODAY CITRUSCOUNTY & next morning HIGH 84 Mostly sunny and LOW pleasant. 58 PAGE A4 www.chronicleonline.com APRIL 13, 2021 Florida’s Best Community Newspaper Serving Florida’s Best Community $1 VOL. 126 ISSUE 187 NEWS BRIEFS Citrus gets weekend soaking Citrus County MICHAEL D. about 3 inches of rain, the of rain that our region the driest months of the (2.02 inches); Lakeland COVID-19 cases BATES vast majority on Sunday. was in need of,” Fulker- year in Florida. (2.40 inches) and Fort According to the Flor- Staff writer The historical average for son said. The National Weather Myers (2.05 inches). ida Department of Health, the month is 2.7 inches, All that rain caused Service (NWS) is forecast- This weekend’s rough said Mark Fulkerson, area lakes to rise about ing mostly dry conditions 10 positive cases were Citrus County got more weather produced two re- rain this weekend than it chief professional engi- 3 inches in a day, he said. to start the week. The only ports of tornadoes: In Bra- reported in Citrus County normally gets for the en- neer with the Southwest “It’ll take about 12 days real chance of rain is denton and Winter Haven. since the latest update. tire month of April. Florida Water Manage- for those 3 inches to natu- Thursday, Saturday and Contact Chronicle re- No new deaths were It didn’t set any rainfall ment District rally drop, so the week- Sunday, with a 30% chance porter Michael D. -

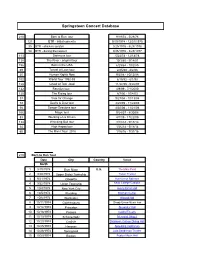

Springsteen Concert Database

Springsteen Concert Database 210 Born to Run tour 9/19/74 - 5/28/76 121 BTR - initial concerts 9/19/1974 - 12/31/1975 35 BTR - chicken scratch 3/25/1976 - 5/28/1976 54 BTR - during the lawsuit 9/26/1976 - 3/25/1977 113 Darkness tour 5/23/78 - 12/18/78 138 The River - original tour 10/3/80 - 9/14/81 156 Born in the USA 6/29/84 - 10/2/85 69 Tunnel of Love tour 2/25/88 - 8/2/88 20 Human Rights Now 9/2/88 - 10/15/88 102 World Tour 1992-93 6/15/92 - 6/1/93 128 Ghost of Tom Joad 11/22/95 - 5/26/97 132 Reunion tour 4/9/99 - 7/1/2000 120 The Rising tour 8/7/00 - 10/4/03 37 Vote for Change 9/27/04 - 10/13/04 72 Devils & Dust tour 4/25/05 - 11/22/05 56 Seeger Sessions tour 4/30/06 - 11/21/06 106 Magic tour 9/24/07 - 8/30/08 83 Working on a Dream 4/1/09 - 11/22/09 134 Wrecking Ball tour 3/18/12 - 9/18/13 34 High Hopes tour 1/26/14 - 5/18/14 65 The River Tour 2016 1/16/16 - 7/31/16 210 Born to Run Tour Date City Country Venue North America 1 9/19/1974 Bryn Mawr U.S. The Main Point 2 9/20/1974 Upper Darby Township Tower Theater 3 9/21/1974 Oneonta Hunt Union Ballroom 4 9/22/1974 Union Township Kean College Campus Grounds 5 10/4/1974 New York City Avery Fisher Hall 6 10/5/1974 Reading Bollman Center 7 10/6/1974 Worcester Atwood Hall 8 10/11/1974 Gaithersburg Shady Grove Music Fair 9 10/12/1974 Princeton Alexander Hall 10 10/18/1974 Passaic Capitol Theatre 11 10/19/1974 Schenectady Memorial Chapel 12 10/20/1974 Carlisle Dickinson College Dining Hall 13 10/25/1974 Hanover Spaulding Auditorium 14 10/26/1974 Springfield Julia Sanderson Theater 15 10/29/1974 Boston Boston Music Hall 16 11/1/1974 Upper Darby Tower Theater 17 11/2/1974 18 11/6/1974 Austin Armadillo World Headquarters 19 11/7/1974 20 11/8/1974 Corpus Christi Ritz Music Hall 21 11/9/1974 Houston Houston Music Hall 22 11/15/1974 Easton Kirby Field House 23 11/16/1974 Washington, D.C.