Download (961Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHAPTER 10 MOLLUSCS 10.1 a Significant Space A

PART file:///C:/DOCUME~1/ROBERT~1/Desktop/Z1010F~1/FINALS~1.HTM CHAPTER 10 MOLLUSCS 10.1 A Significant Space A. Evolved a fluid-filled space within the mesoderm, the coelom B. Efficient hydrostatic skeleton; room for networks of blood vessels, the alimentary canal, and associated organs. 10.2 Characteristics A. Phylum Mollusca 1. Contains nearly 75,000 living species and 35,000 fossil species. 2. They have a soft body. 3. They include chitons, tooth shells, snails, slugs, nudibranchs, sea butterflies, clams, mussels, oysters, squids, octopuses and nautiluses (Figure 10.1A-E). 4. Some may weigh 450 kg and some grow to 18 m long, but 80% are under 5 centimeters in size. 5. Shell collecting is a popular pastime. 6. Classes: Gastropoda (snails…), Bivalvia (clams, oysters…), Polyplacophora (chitons), Cephalopoda (squids, nautiluses, octopuses), Monoplacophora, Scaphopoda, Caudofoveata, and Solenogastres. B. Ecological Relationships 1. Molluscs are found from the tropics to the polar seas. 2. Most live in the sea as bottom feeders, burrowers, borers, grazers, carnivores, predators and filter feeders. 1. Fossil evidence indicates molluscs evolved in the sea; most have remained marine. 2. Some bivalves and gastropods moved to brackish and fresh water. 3. Only snails (gastropods) have successfully invaded the land; they are limited to moist, sheltered habitats with calcium in the soil. C. Economic Importance 1. Culturing of pearls and pearl buttons is an important industry. 2. Burrowing shipworms destroy wooden ships and wharves. 3. Snails and slugs are garden pests; some snails are intermediate hosts for parasites. D. Position in Animal Kingdom (see Inset, page 172) E. -

Structure and Function of the Digestive System in Molluscs

Cell and Tissue Research (2019) 377:475–503 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00441-019-03085-9 REVIEW Structure and function of the digestive system in molluscs Alexandre Lobo-da-Cunha1,2 Received: 21 February 2019 /Accepted: 26 July 2019 /Published online: 2 September 2019 # Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2019 Abstract The phylum Mollusca is one of the largest and more diversified among metazoan phyla, comprising many thousand species living in ocean, freshwater and terrestrial ecosystems. Mollusc-feeding biology is highly diverse, including omnivorous grazers, herbivores, carnivorous scavengers and predators, and even some parasitic species. Consequently, their digestive system presents many adaptive variations. The digestive tract starting in the mouth consists of the buccal cavity, oesophagus, stomach and intestine ending in the anus. Several types of glands are associated, namely, oral and salivary glands, oesophageal glands, digestive gland and, in some cases, anal glands. The digestive gland is the largest and more important for digestion and nutrient absorption. The digestive system of each of the eight extant molluscan classes is reviewed, highlighting the most recent data available on histological, ultrastructural and functional aspects of tissues and cells involved in nutrient absorption, intracellular and extracellular digestion, with emphasis on glandular tissues. Keywords Digestive tract . Digestive gland . Salivary glands . Mollusca . Ultrastructure Introduction and visceral mass. The visceral mass is dorsally covered by the mantle tissues that frequently extend outwards to create a The phylum Mollusca is considered the second largest among flap around the body forming a space in between known as metazoans, surpassed only by the arthropods in a number of pallial or mantle cavity. -

Bulletin of the United States Fish Commission

A REVIEW OF THE CEPHALOPODS OF WESTERN NORTH AMERICA By S. Stillman Berry Stanford University, California Blank page retained for pagination A REVIEW OF THE CEPHALOPODS OF WESTERN NORTH AMERICA. By S. STILLMAN BERRY, Stanford University, California. J1. INTRODUCTION. "The region covered by the present report embraces the western shores of North America between Bering Strait on the north and the Coronado Islands on the south, together with the immediately adjacent waters of Bering Sea and the North Pacific Ocean. No attempt is made to present a monograph nor even a complete catalogue of the species now living within this area. The material now at hand is inadequate to properly repre sent the fauna of such a vast region, and the stations at which anything resembling extensive collecting has been done are far too few and scattered. Rather I have merely endeavored to bring out of chaos and present under one cover a resume of such work as has already been done, making the necessary corrections wherever possible, and adding accounts of such novelties as have been brought to my notice. Descriptions are given of all the species known to occur or reported from within our limits, and these have been made. as full and accurate as the facilities available to me would allow. I have hoped to do this in such a way that students, particularly in the Western States, will find it unnecessary to have continual access to the widely scattered and often unavailable literature on the subject. In a number of cases, however, the attitude adopted must be understood as little more than provisional in its nature, and more or less extensive revision is to be expected later, especially in the case of the large and difficult genus Polypus, which here attains a development scarcely to be sur passed anywhere. -

Turridae (Mollusca: Gastropoda) of Southern Africa and Mozambique

Ann. Natal Mus. Vol. 29(1) Pages 167-320 Pietermaritzburg May, 1988 Turridae (Mollusca: Gastropoda) of southern Africa and Mozambique. Part 4. Subfamilies Drilliinae, Crassispirinae and Strictispirinae by R. N. Kilburn (Natal Museum, Pietermaritzburg) SYNOPSIS 71 species (42 previously undescribed) are covered: Drilliinae (33 species), Strictispirinae (3), Crassispirinae (35). New genera: Orrmaesia, Acinodrillia (Drilliinae); Inkinga (Strictispirinae); Naudedrillia, Nquma, Psittacodrillia, Calcatodrillia, Funa (Crassispirinae). New species: Drilliinae: Acinodrillia viscum, A. amazimba; Clavus groschi; Tylotiella isibopho, T. basipunctata, T. papi/io, T. herberti, T. sulekile, T. quadrata, Agladrillia ukuminxa, A. piscorum; Drillia (Drillia) spirostachys, D. (Clathrodrillia) connelli; Orrmaesia dorsicosta, O. nucella; Splendrillia mikrokamelos, S. kylix, S. alabastrum, S. skambos, S. sarda, S. daviesi. Crassispirinae: Crassiclava balteata; Inquisitor nodicostatus, /. arctatus, I. latiriformis, I. isabella, Funa fraterculus, F. asra; Naudedrillia filosa, N. perardua, N. cerea, N. angulata, N. nealyoungi, N. mitromorpha; Pseudexomilus fenestratus; Ceritoturris nataliae; Nquma scalpta; Haedropleura summa; Mauidrillia felina; Calcatodrillia chamaeleon, C. hololeukos; Buchema dichroma. New generic records: Clavus Montfort, 1810, Tylotiella Habe, 1958, Iredalea Oliver, 1915, Splendrillia Hedley, 1922, Agladrillia Woodring, 1928 (Drilliinae); Paradrillia Makiyama, 1940 (Strictispirinae); Crassiclava McLean, 1971, Pseudexomilus Powell, 1944, Haedropleura -

Phylum Mollusca

Lab exercise 4: Molluscs General Zoology Laborarory . Matt Nelson phylum Mollusca Molluscs The phylum Mollusca (Latin mollusca = “soft”) is the largest, most diverse phylum in the clade Lophotrochozoa. Like the annelids, they are triploblastic eucoelomates that develop from a trochophore larva. However, they do not possess the characteristic segmentation of annelids. Also, unlike annelids, most molluscs possess an open circulatory system. It is thought that closed circulatory systems evolved at least three times in the Animalia: in an ancestor of the Annelida, an ancestor of the Chordates, and within the Mollusca. One group of modern molluscs, the cephalopods, has a closed circulatory system. Organization Molluscs generally have soft, muscular bodies that are protected by a calcareous shell. Molluscs have two main parts of the body: head-foot - Usually involved in locomotion and feeding, the muscular head foot contains most of the sensory structures of the mollusc, as well as the radula that is used for feeding. visceral mass - The viscera of a mollusc are contained in the visceral mass, which is usually surrounded by the mantle, a thick, tough layer of tissues that produces the shell. radular tooth Head Foot odontophore The head of the mollusc contains feeding and sensory structures, and is generally connected to the foot. However, there is a great deal of diversity in the molluscs, with in many adaptations of the foot for various purposes. Most molluscs feed using a radula. The radula is an autapomorphy for molluscs (relative to other animal phyla), which is usually used for scraping food particles such as algae from a substrate. -

Historical and Biomechanical Analysis of Integration and Dissociation in Molluscan Feeding, with Special Emphasis on the True Limpets (Patellogastropoda: Gastropoda)

Historical and biomechanical analysis of integration and dissociation in molluscan feeding, with special emphasis on the true limpets (Patellogastropoda: Gastropoda) by Robert Guralnick 1 and Krister Smith2 1 Department of Integrative Biology and Museum of Paleontology, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720-3140 USA email: [email protected] 2 Department of Geology and Geophysics, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720 USA ABSTRACT Modifications of the molluscan feeding apparatus have long been recognized as a crucial feature in molluscan diversification, related to the important process of gathering energy from the envirornment. An ecologically and evolutionarily significant dichotomy in molluscan feeding kinematics is whether radular teeth flex laterally (flexoglossate) or do not (stereoglossate). In this study, we use a combination of phylogenetic inference and biomechanical modeling to understand the transformational and causal basis for flexure or lack thereof. We also determine whether structural subsystems making up the feeding system are structurally, functionally, and evolutionary integrated or dissociated. Regarding evolutionary dissociation, statistical analysis of state changes revealed by the phylogenetic analysis shows that radular and cartilage subsystems evolved independently. Regarding kinematics, the phylogenetic analysis shows that flexure arose at the base of the Mollusca and lack of flexure is a derived condition in one gastropod clade, the Patellogastropoda. Significantly, radular morphology shows no change at the node where kinematics become stereoglossate. However, acquisition of stereoglossy in the Patellogastropoda is correlated with the structural dissociation of the subradular membrane and underlying cartilages. Correlation is not causality, so we present a biomechanical model explaining the structural conditions necessary for the plesiomorphic kinematic state (flexoglossy). -

Anatomy of Predator Snail Huttonella Bicolor, an Invasive Species in Amazon Rainforest, Brazil (Pulmonata, Streptaxidae)

Volume 53(3):47‑58, 2013 ANATOMY OF PREDATOR SNAIL HUTTONELLA BICOLOR, AN INVASIVE SPECIES IN AMAZON RAINFOREST, BRAZIL (PULMONATA, STREPTAXIDAE) 1 LUIZ RICARDO L. SIMONE ABSTRACT The morpho-anatomy of the micro-predator Huttonella bicolor (Hutton, 1838) is investi- gated in detail. The species is a micro-predator snail, which is splaying in tropical and sub- tropical areas all over the world, the first report being from the Amazon Rainforest region of northern Brazil. The shell is very long, with complex peristome teeth. The radula bears sharp pointed teeth. The head lacks tentacles, bearing only ommatophores. The pallial cavity lacks well-developed vessels (except for pulmonary vessel); the anus and urinary aperture are on pneumostome. The kidney is solid, with ureter totally closed (tubular); the primary ureter is straight, resembling orthurethran fashion. The buccal mass has an elongated and massive odontophore, of which muscles are described; the odontophore cartilages are totally fused with each other. The salivary ducts start as one single duct, bifurcating only prior to insertion. The mid and hindguts are relatively simple and with smooth inner surfaces; there is practically no intestinal loop. The genital system has a zigzag-fashioned fertilization complex, narrow pros- tate, no bursa copulatrix, short and broad vas deferens, and simple penis with gland at distal tip. The nerve ring bears three ganglionic masses, and an additional pair of ventral ganglia connected to pedal ganglia, interpreted as odontophore ganglia. These features are discussed in light of the knowledge of other streptaxids and adaptations to carnivory. Key-Words: Streptaxidae; Carnivorous; Biological invasion; Anatomy; Systematics. -

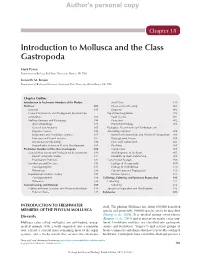

Introduction to Mollusca and the Class Gastropoda

Author's personal copy Chapter 18 Introduction to Mollusca and the Class Gastropoda Mark Pyron Department of Biology, Ball State University, Muncie, IN, USA Kenneth M. Brown Department of Biological Sciences, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA, USA Chapter Outline Introduction to Freshwater Members of the Phylum Snail Diets 399 Mollusca 383 Effects of Snail Feeding 401 Diversity 383 Dispersal 402 General Systematics and Phylogenetic Relationships Population Regulation 402 of Mollusca 384 Food Quality 402 Mollusc Anatomy and Physiology 384 Parasitism 402 Shell Morphology 384 Production Ecology 403 General Soft Anatomy 385 Ecological Determinants of Distribution and Digestive System 386 Assemblage Structure 404 Respiratory and Circulatory Systems 387 Watershed Connections and Chemical Composition 404 Excretory and Neural Systems 387 Biogeographic Factors 404 Environmental Physiology 388 Flow and Hydroperiod 405 Reproductive System and Larval Development 388 Predation 405 Freshwater Members of the Class Gastropoda 388 Competition 405 General Systematics and Phylogenetic Relationships 389 Snail Response to Predators 405 Recent Systematic Studies 391 Flexibility in Shell Architecture 408 Evolutionary Pathways 392 Conservation Ecology 408 Distribution and Diversity 392 Ecology of Pleuroceridae 409 Caenogastropods 393 Ecology of Hydrobiidae 410 Pulmonates 396 Conservation and Propagation 410 Reproduction and Life History 397 Invasive Species 411 Caenogastropoda 398 Collecting, Culturing, and Specimen Preparation 412 Pulmonata 398 Collecting 412 General Ecology and Behavior 399 Culturing 413 Habitat and Food Selection and Effects on Producers 399 Specimen Preparation and Identification 413 Habitat Choice 399 References 413 INTRODUCTION TO FRESHWATER shell. The phylum Mollusca has about 100,000 described MEMBERS OF THE PHYLUM MOLLUSCA species and potentially 100,000 species yet to be described (Strong et al., 2008). -

Evolution of the Radular Apparatus in Conoidea (Gastropoda: Neogastropoda) As Inferred from a Molecular Phylogeny

MALACOLOGIA, 2012, 55(1): 55−90 EVOLUTION OF THE RADULAR APPARATUS IN CONOIDEA (GASTROPODA: NEOGASTROPODA) AS INFERRED FROM A MOLECULAR PHYLOGENY Yuri I. Kantor1* & Nicolas Puillandre2 ABSTRACT The anatomy and evolution of the radular apparatus in predatory marine gastropods of the superfamily Conoidea is reconstructed on the basis of a molecular phylogeny, based on three mitochondrial genes (COI, 12S and 16S) for 102 species. A unique feeding mecha- nism involving use of individual marginal radular teeth at the proboscis tip for stabbing and poisoning of prey is here assumed to appear at the earliest stages of evolution of the group. The initial major evolutionary event in Conoidea was the divergence to two main branches. One is characterized by mostly hypodermic marginal teeth and absence of an odontophore, while the other possesses a radula with primarily duplex marginal teeth, a strong subradular membrane and retains a fully functional odontophore. The radular types that have previously been considered most ancestral, “prototypic” for the group (flat marginal teeth; multicuspid lateral teeth of Drilliidae; solid recurved teeth of Pseudomelatoma and Duplicaria), were found to be derived conditions. Solid recurved teeth appeared twice, independently, in Conoidea – in Pseudomelatomidae and Terebridae. The Terebridae, the sister group of Turridae, are characterized by very high radular variability, and the transformation of the marginal radular teeth within this single clade repeats the evolution of the radular apparatus across the entire Conoidea. Key words: Conoidea, Conus, radula, molecular phylogeny, evolution, feeding mechanisms, morphological convergence, character mapping. INTRODUCTION the subradular membrane, transferred to the proboscis tip (Figs. 2, 4), held by sphincter(s) Gastropods of the superfamily Conoidea in the buccal tube (Figs. -

Radular Force Performance of Stylommatophoran Gastropods (Mollusca) with Distinct Body Masses Wencke Krings1,3*, Charlotte Neumann1, Marco T

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Radular force performance of stylommatophoran gastropods (Mollusca) with distinct body masses Wencke Krings1,3*, Charlotte Neumann1, Marco T. Neiber2, Alexander Kovalev3 & Stanislav N. Gorb3 The forces exerted by the animal’s food processing structures can be important parameters when studying trophic specializations to specifc food spectra. Even though molluscs represent the second largest animal phylum, exhibiting an incredible biodiversity accompanied by the establishment of distinct ecological niches including the foraging on a variety of ingesta types, only few studies focused on the biomechanical performance of their feeding organs. To lay a keystone for future research in this direction, we investigated the in vivo forces exerted by the molluscan food gathering and processing structure, the radula, for fve stylommatophoran species (Gastropoda). The chosen species and individuals have a similar radular morphology and motion, but as they represent diferent body mass classes, we were enabled to relate the forces to body mass. Radular forces were measured along two axes using force transducers which allowed us to correlate forces with the distinct phases of radular motion. A radular force quotient, AFQ = mean Absolute Force/bodymass0.67, of 4.3 could be determined which can be used further for the prediction of forces generated in Gastropoda. Additionally, some specimens were dissected and the radular musculature mass as well as the radular mass and dimensions were documented. Our results depict the positive correlation between body mass, radular musculature mass, and exerted force. Additionally, it was clearly observed that the radular motion phases, exerting the highest forces during feeding, changed with regard to the ingesta size: all smaller gastropods rather approached the food by a horizontal, sawing-like radular motion leading to the consumption of rather small food particles, whereas larger gastropods rather pulled the ingesta in vertical direction by radula and jaw resulting in the tearing of larger pieces. -

Digestive System & Feeding in Pila Globosa

Digestive System & Feeding In Pila globosa The digestive system of Pila Globosa comprises: 1. A tubular alimentary canal 2. A pair of salivary glands 3. A large digestive gland (i) Alimentary Canal: The alimentary canal is distinguished into three regions, viz: 1. The foregut or stomodaeum including the buccal mass and oesophagus, 2. The midgut or mesenteron consisting of stomach and intestine, and 3. The hindgut or proctodaeum comprising the rectum. The midgut alone is lined by endoderm, while the other two are lined by ectoderm. 1. Foregut: The foregut includes the mouth, buccal mass and oesophagus. (i) Mouth: The mouth is a narrow vertical slit situated at the end of snout. There are no true lips but the plicate edges alone serve as secondary lips. (ii) Buccal Mass: The mouth leads into a large cavity of buccal mass or pharynx having thick walls with several sets of muscles. The anterior part of the cavity of buccal mass is vestibule. Behind the vestibule are two jaws hanging from the roof of the buccal mass. The jaws bear muscles and their anterior edges have teeth-like projections for cutting up vegetable food. Buccal Cavity: Behind the jaws is a large buccal cavity. On the floor of the buccal cavity is a large elevation called odontophore. The front part of odontophore has a furrowed subradular organ which helps in cutting food. The odontophore has protractor and retractor muscles and two pairs of cartilages, a pair of triangular superior cartilages which project into the buccal cavity, and a pair of large S-shaped lateral cartilages. -

The Helfflinthological Society of Washington ,'-R*.I- :;.-V' '..--Vv -' 7 3 --,/•;,•¥'- -'•••^~''R.H

Volume 48 Number 2 PROCEEDINGS The Helfflinthological Society of Washington ,'-r*.i- :;.-V' '..--vV -' 7 3 --,/•;,•¥'- -'•••^~''r.h. ^ semiannual journal /of research devofed to He/minfhibleigy cind a// branches ,of Paras/fo/ogy ••".,-,• -•-': ••'•'.'•' V -.?>••; ',..'• •' :"-'-*$i . ,••• '..'.„ '".-•„•//• " r ' ' • l\" "A V SilipjDOrted in part by the ' ';v.^'Xy ? : Dayton H. Ransom MernoridlJrost Fund i/7 ; •..-•''.'• "'t'" ' • ''?:-'. ~^' ' '/...;'- . '.'' " '~ , '-•_•_. - ''•' '}( Vs jSubscription $18.00 a Volume; Foreign, $19.00 -; Y.= V:'^''VI-'. .; > ''_'•.. ":':': ->r^ ' >..- • -'". --; "'!"-' •''•/' ' CONTENTS . :. '^.^ -•v~;'-. '•" 'BAKER, "JMicpAELvR. Rede^cription of,}Pneutnonema tiliquae Jphnstori, (<1916_ (Nematodaiijihab'diasidae) from an Australian Snk _,r ___ ".iL.:vi-^-— L.— ^. _v. .1 '159 CAMISHIQN, GpAiNE lyi., WjLLiyvM J. BACHA, JR., AI^D \Y &TEMPEN, :The /Circunioval Precipitate^ and Cercarierihulien Reaktion" ; _of Auytrpbil- ; - harzia variglandis ... ^-.-^..:._-___ _ — —^-1—-.—-—^— —It^— -—-,-—!-— 1—,: ___202 ^ATALANOX PAUL A- AND FRANK J. EroESi Piagiopqrus gyrinophili sp, -n. , i (Tfematoda: Opecoelidae) xfrom Gyrinophilus porphyriticus duryi Tand Pseuddlritonruber(Cavtdata; Pletjhlodontidae) .^— - _____ *--..—/ —-L-—..—i._.--- 198 ;i)EARpOREF, ^THOMAS L. (AND ROBIN ;M. OvERSTREET. Larval Hysterothyl- ,-'- acium '(^Thynnascaris) ...(Nematoda: Ani?akidae)v frorh "Fishes and Jnyerte- ^the'>Gulf of^Mexico ..'..fL-.', ___ ju-.l.'.tu ___ ^'--*.T.^.--— ..— --1- ____ I.l---i._l-- v CHRISTIAN, LLEN D. JOHNSON, AND EDMOUR BLOUIN. Nedscuk pyri- ,- fe>rm/5 ^Chandler, 1951 (Trematoda:iDipl6stomatidae);;Redescription I'and/'Jiici- "dence in Fishes from Brule Creek, South Dakota — :„ _. vj- ____ L. .—'^ — !• ____ -v-l~ ,177 FERRIS, V. R., J. M. FERRIS, AN!D C-:G. GOSECO. Phylpgenetic arid Biogeograph- • •* 'ic /.Hypotheses Ain Leptonchidae (Nejnatoda: ipprylaimida) and a ^New Glassi- /:" ;;fieation -^...,..... IL_- ____T ___ —_„..-%_.__ iL- ___ ....V...- ___ ; ___________ ^-.^.v.I:_.k-.