Biopolitical Mediatization in the Death of David Goodall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Revellers at New Year’S Eve 2018 – the Night Is Yours

AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING CORPORATION ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Revellers at New Year’s Eve 2018 – The Night is Yours. Image: Jared Leibowtiz Cover: Dianne Appleby, Yawuru Cultural Leader, and her grandson Zeke 11 September 2019 The Hon Paul Fletcher MP Minister for Communications, Cyber Safety and the Arts Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 Dear Minister The Board of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation is pleased to present its Annual Report for the year ended 30 June 2019. The report was prepared for section 46 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013, in accordance with the requirements of that Act and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation Act 1983. It was approved by the Board on 11 September 2019 and provides a comprehensive review of the ABC’s performance and delivery in line with its Charter remit. The ABC continues to be the home and source of Australian stories, told across the nation and to the world. The Corporation’s commitment to innovation in both storytelling and broadcast delivery is stronger than ever, as the needs of its audiences rapidly evolve in line with technological change. Australians expect an independent, accessible public broadcasting service which produces quality drama, comedy and specialist content, entertaining and educational children’s programming, stories of local lives and issues, and news and current affairs coverage that holds power to account and contributes to a healthy democratic process. The ABC is proud to provide such a service. The ABC is truly Yours. Sincerely, Ita Buttrose AC OBE Chair Letter to the Minister iii ABC Radio Melbourne Drive presenter Raf Epstein. -

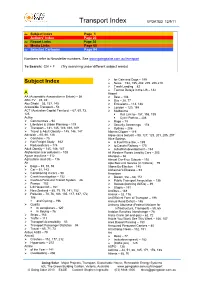

Transport Index UPDATED 12/9/11

Transport Index UPDATED 12/9/11 [ Subject Index Page 1 [ Authors’ Index Page 23 [ Report Links Page 30 [ Media Links Page 60 [ Selected Cartoons Page 94 Numbers refer to Newsletter numbers. See www.goingsolar.com.au/transport To Search: Ctrl + F (Try searching under different subject words) ¾ for Cats and Dogs – 199 Subject Index ¾ News – 192, 195, 202, 205, 206,210 ¾ Trash Landing – 82 ¾ Tarmac Delays in the US – 142 A Airport AA (Automobile Association in Britain) – 56 ¾ Best – 108 ABC-TV – 45, 49 ¾ Bus – 28, 77 Abu Dhabi – 53, 137, 145 ¾ Emissions – 113, 188 Accessible Transport – 53 ¾ London – 120, 188 ACT (Australian Capital Territory) – 67, 69, 73, ¾ Melbourne 125 Rail Link to– 157, 198, 199 Active Cycle Path to – 206 ¾ Communities – 94 ¾ Rage – 79 ¾ Lifestyles & Urban Planning – 119 ¾ Security Screenings – 178 ¾ Transport – 141, 145, 149, 168, 169 ¾ Sydney – 206 ¾ Travel & Adult Obesity – 145, 146, 147 Alberta Clipper – 119 Adelaide – 65, 66, 126 Algae (as a biofuel) – 98, 127, 129, 201, 205, 207 ¾ Carshare – 75 Alice Springs ¾ Rail Freight Study – 162 ¾ A Fuel Price like, – 199 ¾ Reduced cars – 174 ¾ to Darwin Railway – 170 Adult Obesity – 145, 146, 147 ¾ suburban development – 163 Afghanistan (car pollution) – 108 All Western Roads Lead to Cars – 203 Agave tequilana – 112 Allergies – 66 Agriculture (and Oil) – 116 Almost Car-Free Suburb – 192 Air Alps Bus Link Service (in Victoria) – 79 ¾ Bags – 89, 91, 93 Altona By-Election – 145 ¾ Car – 51, 143 Alzheimer’s Disease – 93 ¾ Conditioning in cars – 90 American ¾ Crash Investigation -

Annual Report 2018 Australian Broadcasting Corporation

AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING CORPORATION CORPORATION BROADCASTING AUSTRALIAN VOLUME II ANNUAL REPORT 2018 REPORT ANNUAL Yours, Now & into the Future ANNUAL REPORT 2018 Image: Tom Gleeson, Charlie Pickering, Adam Briggs and Kitty Flanagan in The Weekly with Charlie Pickering 2 AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING CORPORATION ANNUAL REPORT 2018 “As the national broadcaster, we are uniquely positioned to tell Australian stories and bring people together to explore and understand issues that matter to them, and to reflect Australia’s culture and diversity. There is something for everyone at the ABC.” David Anderson, Director ABC Entertainment & Specialist 3 4 AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING CORPORATION ANNUAL REPORT 2018 Contents Quality, Distinctive Content in 2017–18 6 Yours in the Community 40 Audience Engagement 56 Annual Performance Statements 80 Working at the ABC 90 Responsibility 114 Accountability 132 Financial Statements 142 Appendices 200 Compliance Index 260 Glossary & Index 262 In Volume I you will find: Welcome The ABC is Yours Yours for quality, distinctive content Purpose and vision Yours into the Future Snapshot of 2017–18 Highlights 2017–18: Extraordinary, relevant and valued content An outstanding audience experience Reaching more people Building a great place to work The ABC Leadership Team The ABC Board Contents 5 Image: Aaliyah, Jaral and Sharmika in Shame Quality, distinctive content in 2017–18 6 AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING CORPORATION ANNUAL REPORT 2018 7 Genre Teams Content team redesign The Investing in Audiences strategy is all about creating extraordinary content that is relevant and valued by all Australians. To this end, and to better equip ABC content teams to address fast-moving audience trends, improve collaboration and speed decision-making, new content teams were consolidated in February 2018 – arranged around content and audiences rather than broadcast platforms. -

PUBLIC - Art in the City 9.4.1 - Attachment 003 Sponsorship Report for the City of Vincent

PUBLIC - Art in the City 9.4.1 - Attachment 003 Sponsorship Report for the City of Vincent ‘800 Hours’ by 2501, 2014. Photograph by Bewley Shaylor. 9.4.1 - Attachment 003 PUBLIC - Art in the City The inaugural PUBLIC – Art in the City event was a resounding success: in collaboration with our partners, FORM delivered 35 wall-based public artworks for the city over 14 exciting days. In addition to these world-class artworks, PUBLIC transformed the city with temporary installations, digital projections, exhibitions, workshop programming and street parties, to truly celebrate art as a public good. PUBLIC: KEY ACHIEVEMENTS • PUBLIC – Art in the City: • Artist residencies, workshop programming and a laneway event in the City of Vincent: January-April, 2014 • Dear William, a dedication to William Street, an exhibition of urban art, temporary installation, performance and photography celebrating the history and diversity of William Street • 35 public artworks across Perth and Northbridge • 45 local, national and international artist engaged over the 2 week period • Nasty Goreng exhibition by Yok and Sheryo at Turner Galleries: 21 March-19 April, 2014 • PUBLIC Salon, an exhibition of work by PUBLIC artists at FORM Gallery • PUBLIC House, 2 days of events in Wolf Lane including temporary installations, a pop-up bar, DJs and street food from the local businesses • PUBLIC – Art in the Pilbara: Delivery of urban art in the unique landscape of the Pilbara • PUBLIC – 100 Hampton Road: Delivery of transformative artworks at Foundation Housing’s100 Hampton Road lodging house in Fremantle (continuing project) Sheryo (left) and The Yok (right) working on their mural at Turner Galleries, April, 2014. -

ABC Annual Report 2016

Annual Report 2016 FROM THE EVERYDAY TO THE EXTRAORDINARY Storm Brewing by ABC Open contributor davetomo. Wedderburn, Victoria. New South Wales – Ultimo ABC Ultimo Centre 700 Harris Street Ultimo NSW 2007 GPO Box 9994 Sydney NSW 2001 Tel. +61 2 8333 1500 abc.net.au 6 October 2016 Senator the Hon Mitch Fifield Minister for Communications Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 Dear Minister The Board of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation is pleased to present the Annual Report for the year ended 30 June 2016. The Report is prepared in accordance with the requirements of Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation Act 1983, and was approved by a resolution of the Board on 21 September 2016. It provides a comprehensive review of the ABC’s performance in relation to its legislative mandate. The editorial theme of this year’s report—From the Everyday to the Extraordinary—highlights the ABC’s role in reflecting and reporting on matters that are important to the lives of Australians, bringing them the information they need every day, and the extraordinary stories that contribute to our national identity. Yours sincerely James Spigelman AC QC Chairman ii AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING CORPORATION ANNUAL REPORT 2016 Contents ONE TWO THREE FOUR ABOUT THE ABC AUDIENCE INSIDE THE ABC CORPORATE ABC services 4 EXPERIENCES Editorial quality 80 RESPONSIBILITY ABC Board Audience trends 30 Infrastructure Corporate responsibility 102 of Directors 9 Online 32 and operations 84 Corporate Board Directors’ -

ABC PERTH OPEN HOUSE DAY Saturday 16 November

ABC PERTH OPEN HOUSE DAY Saturday 16 November Time ABC personalities The Heights cast The Heights ABC TV show Nadia Mitsopoulos ABC Radio Perth Breakfast Russell Woolf ABC Radio Perth Breakfast 9am - 10am Jessica Strutt ABC Radio Perth Focus Barry Nichols ABC Radio Perth Early Mornings Clint Thomas ABC NEWS Belinda Varischetti ABC WA Country Hour Sabrina Hahn ABC Radio Perth Roots and Shoots Christine Layton ABC Radio Perth Saturday Breakfast Michael Tetlow ABC NEWS Belinda Varischetti ABC WA Country Hour The Heights cast The Heights ABC TV show 10am - 11am Nadia Mitsopoulos ABC Radio Perth Breakfast Russell Woolf ABC Radio Perth Breakfast Barry Nichols ABC Radio Perth Early Mornings Clint Thomas ABC NEWS Jessica Strutt ABC Radio Perth Focus The Heights Cast The Heights ABC TV show Michael Tetlow ABC NEWS Christine Layton ABC Radio Perth Saturday Breakfast Nadia Mitsopoulos ABC Radio Perth Breakfast 11am - Noon Russell Woolf ABC Radio Perth Breakfast Jessica Strutt ABC Radio Perth Focus Barry Nichols ABC Radio Perth Early Mornings Clint Thomas ABC NEWS Belinda Varischetti ABC WA Country Hour Geoff Hutchison ABC Radio Perth Drive James McHale ABC NEWS Ben Cameron ABC Grandstand Irena Ceranic ABC NEWS Gillian O'Shaughnessy ABC Radio Perth Afternoons Noon - 1pm Brad McCahon ABC Radio Perth Afternoons Pamela Medlen ABC NEWS Charlotte Hamlyn ABC NEWS Michael Tetlow ABC NEWS Briana Shepherd ABC NEWS Gillian O'Shaughnessy ABC Radio Perth Afternoons Brad McCahon ABC Radio Perth Afternoons Pamela Medlen ABC NEWS Charlotte Hamlyn ABC NEWS 1pm - 2pm Geoff Hutchison ABC Radio Perth Drive James McHale ABC NEWS Ben Cameron ABC Grandstand Briana Shepherd ABC NEWS Irena Ceranic ABC NEWS Pamela Medlen ABC NEWS Charlotte Hamlyn ABC NEWS Geoff Hutchison ABC Radio Perth Drive James McHale ABC NEWS 2pm - 3pm Ben Cameron ABC Grandstand Briana Shepherd ABC NEWS Gillian O'Shaughnessy ABC Radio Perth Afternoons Brad McCahon ABC Radio Perth Afternoons Irena Ceranic ABC NEWS.