1 Kelly, Piers. 2012. Your Word Against Mine: How a Rebel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

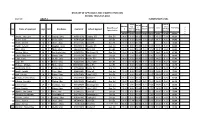

District: ELEMENTARY LEVEL REGISTRY of APPLICANTS FOR

REGISTRY OF APPLICANTS FOR TEACHER I POSITION SCHOOL YEAR 2017-2018 District: UBAY 2 ELEMENTARY LEVEL No.of Comm. LET/PB Educatio Year Specializ Skills/ Major/Area of ET Interview Demo Final Rating R No. Name of Applicant Age SEX Residence Contact # School Applied n Teaching ed Skills EPT/Psyc A Specialization Rating Experienc ho Test N (20 pts) (15 pts) (15 pts) (10 pts) (10 pts) (15 pts) (15 pts) (100 pts) K 1 Amolat , Ma. Luisa 24 F Cagting , Ubay 9355316796 Cagting ES Gen. Ed. 14.40 0.00 11.00 10.00 10.00 15.00 7.83 68.23 2 Boiser , Joan 23 F Benliw, Ubay 9354165264 Benliw ES Gen Ed. 12.60 1.50 12.00 5.00 8.67 14.75 9.50 64.02 3 Bonol , Gersild 24 F Union , Ubay 9120221076 Union ES Gen Ed. 12.00 0.00 12.00 8.00 32.00 4 Carillo , Jenelyn 24 F Juagdan , Ubay 9422864516 Juagdan ES Gen. Ed. 15.00 0.00 12.00 5.00 9.30 14.25 9.33 64.88 5 Ibale , Vina 22 F Tipolo, Ubay 9460883199 Tipolo ES Gen Ed. 14.40 0.00 12.00 5.00 9.18 14.38 8.67 63.63 6 Inojales, Meliza 28 F San Vicente, Ubay 9354753703 San Vicente ES Gen. Ed. 12.60 3.30 11.00 9.75 9.70 14.47 6.83 67.65 7 Libuton, Maychelle 24 F Biabas, Ubay 9355797289 Ubay II CES Gen Ed. 14.40 2.80 11.00 10.00 9.80 14.10 6.50 68.60 8 Lingo , Hazel 26 F Imelda , Ubay 9261792718 Imelda ES Gen Ed. -

DM-No.-296-S.-2011.Pdf

RepLiirhcof the Dhrilpprnes Deparlmentof Edr-rcarron Regicr,u'ii, Centi-ai Visavas DlVl'-;11ryUF BU'J(JL Ctt1,lf TagSilara' October24 2011 DIVISIONMEMORANDUM NaZqGs aell TO FclucatronSupervisorslpSD.S Coor-djnatrng er.incipals/Eiementan, arrciSeourrriary School Hearts PLJBI.IC-PRIVATF PARTNERSHIP (PPP!PROGRAIU SITE APPRAISAL Oneof the actrvrtresof the prrbhc_pr.rvatepartnershrp {ppp)School Buildrng prcgram ts app,'atsa!cl lhe prcpcsedreopient schools. fhe slte site'apprarsalactrvrt,es are scheduledfor lhe wnoternonln ol November{tndu$ve}20.1 1 Thereare $x teams to condttctthe r;lro appralsalPFSED Manila freldrng three protect Fngineersrn addittcn lc cul"lhree {3) {3) DtvtsicnProiect Fngrne.ers and Divrsron physroal Slalito copeup $iltn lhe oeadirne Fac,lilres In thts reqardthe dtvtston offtce wtll prcvtrje the transportatron distrrcl facrlrtv'c io thedrstrrct office and the i^*llprcvrdelhe acccrnrncdaticn ct each tea,,n-vPr/rr('r'\''r Yorrrcoo'eratron on thrsactrvirv rsenicrnerl f.r thesuc-cess of the proqram Travelrng expensesof the DivtstonProtect Enqrneersarirj the DrvrsronFhysrcai slafl shall DrvrsrcnMooF Fund: sublecl r'r be ,.*T[il.,:nainst i;ruar,rr*;;; ,rot rli,t,ig ,uru,,no LORNAE MNCES,Ph.D..CESO V SchooisDivrsron Superrnlendent ;1 ITINERARYOF TRAVEL Nameoi DPE: ROMEOREX ALABA of Travel To conduct Site Appralsalfor PPP Purpose '-'.'.- - -t Name of School I Date i--- o*:ion i --- MuniiiPaiiry 1 REX loi;i ,Buerravista lBago !-s- , NOV*7 E;il F-elrt- -, -, ilsnqr'o;i - i4cryu!.li i:,::H*Ti"i" l lc$ur-11E$ -e lponot igrenavl-le i Nov - - ,anhn, jaG;t"i.i" lbimoui:ilFt i:-"-rqlBotrol i;ili iau.nuu'it' NOV-q l.grrnio*rr jCawag-.'::i-: E"r.,"fHnnnf Ductlavt3La :.: ff: -. -

PHL-OCHA-Bohol Barangay 19Oct2013

Philippines: Bohol Sag Cordoba Sagasa Lapu-Lapu City Banacon San Fernando Naga City Jagoliao Mahanay Mahanay Gaus Alumar Nasingin Pandanon Pinamgo Maomawan Handumon Busalian Jandayan Norte Suba Jandayan Sur Malingin Western Cabul-an San Francisco Butan Eastern Cabul-an Bagacay Tulang Poblacion Poblacion Puerto San Pedro Tugas Taytay Burgos Tanghaligue San Jose Lipata Saguise Salog Santo Niño Poblacion Carlos P. Garcia San Isidro San Jose San Pedro Tugas Saguise Nueva Estrella Tuboran Lapinig Corte Baud Cangmundo Balintawak Santo Niño San Carlos Poblacion Tilmobo Carcar Bonbonon Cuaming Bien Unido Mandawa Campao Occidental Rizal San Jose San Agustin Nueva Esperanza Campamanog San Vicente Tugnao Santo Rosario Villa Milagrosa Canmangao Bayog Buyog Sikatuna Jetafe Liberty Cruz Campao Oriental Zamora Pres. Carlos P. Garcia Kabangkalan Pangpang San Roque Aguining Asinan Cantores La Victoria Cabasakan Tagum Norte Bogo Poblacion Hunan Cambus-Oc Poblacion Bago Sweetland Basiao Bonotbonot Talibon San Vicente Tagum Sur Achila Mocaboc Island Hambongan Rufo Hill Bantuan Guinobatan Humayhumay Santo Niño Bato Magsaysay Mabuhay Cabigohan Sentinila Lawis Kinan-Oan Popoo Cambuhat Overland Lusong Bugang Cangawa Cantuba Soom Tapon Tapal Hinlayagan Ilaud Baud Camambugan Poblacion Bagongbanwa Baluarte Santo Tomas La Union San Isidro Ondol Fatima Dait Bugaong Fatima Lubang Catoogan Katarungan San Isidro Lapacan Sur Nueva Granada Hinlayagan Ilaya Union Merryland Cantomugcad Puting Bato Tuboran Casate Tipolo Saa Dait Sur Cawag Trinidad Banlasan Manuel M. Roxas -

DM-No.-098-S.-2020.Pdf

Bt*nhtic st tle Sllilf$$i$e$ &slisrtr$s$t sf Sbu*stisn itegi*n tr'Il * {.'}-XT-{{A{, \:lS.{\'-{$ scHosls sruIsl&f{ oF B0}N0r- Office of the Schools Division $uperintendent February 24,20?,* D31)"ISIOIT I?IEM{}NAIS SUM $*.q-f8' s. 2o2o fB*Til BIIILDI1YG ACTIIIT?T {ffi*atal l{*altb S*nagcment Frotoeel-GAl} Cosnpoaent} TO " : fiilIIHP F8O.TECT OWETR SDI'CATIT}H FBOGRAS SI'FER\NSOII IIT EI}IDAIIrCE ASD VAI,I'ES EtrT}CILTIOS DAXS rOCAt pEBS(}IT ffiE$TCAL $;rETCEB DrllIsxs$ 03' StlHoL Rs{tr$"rE8tD omsAfiss so$xsEr,olt,s IS? Coor*iastsr-In*ba*g* ISf$e $choal trEst-f 1, e, S FS*$e, ELEHEII"*5I? and $ECOI$B.*.RY B*HSOL &I}HUTIS?XA?GRS 1. ?his Olfice announces the conduct of the Team-Building Aetivities in the pilot implements.tion of Mental Heatth Ma:ragement Protoeol {MHMP} ?CI20 on the follouring schedules: Mareh 5-7. ?S20 {Thurxd*y-$aturday}- Ubay I I}istrict Participants lv€arch 1S-21, 2*20 {Thursday-satr"uday} IJbay Distriet ? Farticipants March26*?8, 202C {?hursda-v-Saturday} Ubay 3 District Pa.rticipants Venue: BPS?EA Br:ildizrg, Tagbilaran Citj' 2. Particip*nis to this three-day Team-Brlilding activities &re the following: Vakres and Guida:rce Education Program Suprviscr Pmject Orruner Division *f Bahol Register+d Guidance Caunseior* {R0Cs}-Faci[ilatsrs ' PSDSslActing PSDSs in th* districts Eleme*tar-y and Secondary Schcol Administrators in the t}ree districts andomly $ele*ted Elemente.4r arrd $eccndary $choal Teachers as Pilct Implementers of tlre Prograra. -

Integrated Natural Resources and Environmental Management Project Rehabilitation of Lundag-San Vicente and Lundag Proper-Cogonon Access Road in Pilar, Bohol

Initial Environmental Examination April 2018 PHI: Integrated Natural Resources and Environmental Management Project Rehabilitation of Lundag-San Vicente and Lundag Proper-Cogonon Access Road in Pilar, Bohol Prepared by the Municipality of Pilar, Province of Bohol for the Asian Development Bank. i CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 15 March 2018) The date of the currency equivalents must be within 2 months from the date on the cover. Currency unit – peso (PhP) PhP 1.00 = $ 0.019254 $1.00 = PhP 51.9367 ABBREVIATIONS ADB Asian Development Bank BDC Barangay Development Council BUB Bottom-Up Budgeting CNC Certificate of Non-Coverage CSC Construction Supervision Consultant CSO Civil Society Organization DED Detail Engineering Design DENR Department of Environment and Natural Resources DILG Department of Interior and Local Government DSWD Department of Social Welfare and Development ECA Environmentally Critical Area ECC Environmental Compliance Certificate ECP Environmentally Critical Project EHSM Environmental Health and Safety Manager EIA Environmental Impact Assessment EIS Environmental Impact Statement EMB Environmental Management Bureau ESS Environmental Safeguards Specialist GAD Gender and Development IEE Initial Environmental Examination INREMP Integrated Natural Resources and Environment Management Project IP Indigenous People IROW Infrastructure Right of Way LGU Local Government Unit LPRAT Local Poverty Reduction Action Team MDC Municipal Development Council MPN Most Probable Number NAAQ National Ambient Air Quality Guidelines NCB National -

REPUBLIC of the PHILIPPINES Senate

REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES Senate Pasaycity ' SESSION NO. 89 Tuesday, May 24,2005 THIRTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST REGULAR SESSION SESSION NO. 89 Tuesday, May 24, 2005 CALL TO ORDER With 16 senators present, the Chair declared the presence of a quorum. At 3:44 pm, the Senate President, Hon. Franklin M. Drilon, called the session to order. Senators Gordon, Lim, Osmefia and Roxas arrived after the roll call. PRAYER Sen. Juan M. Flavier read the following prayer Senator Biazon was on official mission abroad. prepared by Senator Recto: Senator Revilla was on official mission. As we humbly come before the Lord and seek His face, Senator Recto was absent. May we serve You first and honor You most. As the President signed into law the Value- APPROVAL OF THE JOURNAL Added Tax Law, we pray, May the people to impose the law, gain Upon motion of Senator Pangilinan, there being greater independence, exercising utmost, no objection, the Body dispensed with the reading of responsibility for our precious resources. Grant us, 0, Lord, justice in our courts, bequest the Journal of Session No. 88 and considered it &dom in our government, bestow upon approved. our national leaders the strength and endow upon them the integrity to serve REFERENCE OF BUSINESS the people with all their might and heart. Lord, we pray, that these men and women The Secretary of the Senate read the following will be granted good judgment, guidance matters and the Chair made the corresponding and strength to fulfill their important roles. referrals: Amidst crises and call for national sobriety, we call on Your Name, MESSAGES FROM THE HOUSE Give us the power and courage to face up to OF REPRESENTATIVES this challenge. -

ANNEXES Volum

Annexes ANNEXES Volum e 3 Part I Supporting Tables Table Title Page I-A.1 Detailed Physiographic Description by Land System and by City/M unicipality, Province of Bohol ............................................. I-1 A.2 Soil Type Distribution by Land Topography/Relief per City/M unicipality, Province of Bohol .............................................. I-6 A.3 Soil Attributes: Soils Depth and Description, Soil Texture and Reaction, and Soil Fertility Status by City/M unicipality, Province of Bohol ............................................................................ I-9 A.4 Detailed Inventory of the NIPAS Areas in the Province of Bohol ............................................................................................ I-11 A.5 Bat Species in the Province of Bohol (As of M ay 2005) .............. I-13 A.6 List of W ildlife Species per M unicipality/City, Province of Bohol I-14 A.7 M ajor M ineral, M etallic and Non-M etallic Deposits of Bohol, M ay 2005 ............................................................................ I-26 A.8a Non-M etallic M ineral Deposits of Bohol, M ay 2005 .................... I-27 A.8b Ore Reserves in the Province of Bohol, M ay 2005 ...................... I-27 A.9 Landslides/Subsidence/Slope Failure Incidences in Bohol (As of M ay 2005) ............................................................................. I-28 A.10 Flood Prone Areas in Bohol (As of M ay 2005) .............................. I-29 A.11 Total Population and Growth Rate, Num ber of Households and Average HH Size and Population Density, Province of Bohol; M ay 2000 Census ............................................................................ I-30 A.12 Projected Population by Age Group, Province of Bohol; CY 2000 – 2020 ................................................................................ I-32 A.13 Ten (10) Leading Causes of M orbidity, Num ber and Rate Per 100,000 Population in 2004 Com pared to the Past 5-Years Average (1999-2003), Province of Bohol .................................... -

Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population BOHOL 1,255,128 ALBURQUERQUE 9,921 Bahi 787 Basacdacu 759 Cantiguib 5

2010 Census of Population and Housing Bohol Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population BOHOL 1,255,128 ALBURQUERQUE 9,921 Bahi 787 Basacdacu 759 Cantiguib 555 Dangay 798 East Poblacion 1,829 Ponong 1,121 San Agustin 526 Santa Filomena 911 Tagbuane 888 Toril 706 West Poblacion 1,041 ALICIA 22,285 Cabatang 675 Cagongcagong 423 Cambaol 1,087 Cayacay 1,713 Del Monte 806 Katipunan 2,230 La Hacienda 3,710 Mahayag 687 Napo 1,255 Pagahat 586 Poblacion (Calingganay) 4,064 Progreso 1,019 Putlongcam 1,578 Sudlon (Omhor) 648 Untaga 1,804 ANDA 16,909 Almaria 392 Bacong 2,289 Badiang 1,277 National Statistics Office 1 2010 Census of Population and Housing Bohol Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population Buenasuerte 398 Candabong 2,297 Casica 406 Katipunan 503 Linawan 987 Lundag 1,029 Poblacion 1,295 Santa Cruz 1,123 Suba 1,125 Talisay 1,048 Tanod 487 Tawid 825 Virgen 1,428 ANTEQUERA 14,481 Angilan 1,012 Bantolinao 1,226 Bicahan 783 Bitaugan 591 Bungahan 744 Canlaas 736 Cansibuan 512 Can-omay 721 Celing 671 Danao 453 Danicop 576 Mag-aso 434 Poblacion 1,332 Quinapon-an 278 Santo Rosario 475 Tabuan 584 Tagubaas 386 Tupas 935 Ubojan 529 Viga 614 Villa Aurora (Canoc-oc) 889 National Statistics Office 2 2010 Census of Population and Housing Bohol Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and -

LIST of BFAR 7 LIVELIHOOD PROJECTS IMPLEMENTED for CY 2012 BOHOL Name of Project Barangay/Municipality/Province Name of Association No

LIST OF BFAR 7 LIVELIHOOD PROJECTS IMPLEMENTED FOR CY 2012 BOHOL Name of Project Barangay/Municipality/Province Name of Association No. of Project Cost Year/Funding Source Beneficiaries 2012 establishment A. Aquaculture SEAWEED GROW-OUT Tintinan, Ubay, Bohol Tintinan Fisherfolk Association 15 37,500.00 SEAWEED GROW-OUT Tres Reyes, Ubay, Bohol Tres Reyes Fisherfolk Association 15 37,500.00 SEAWEED GROW-OUT Humay-humay, Ubay, Bohol Humay-humay Fisherfolk Association 15 37,500.00 SEAWEED GROW-OUT Catmonan, Calape, Bohol Catmonan Fisherfolk Association 15 37,500.00 SEAWEED GROW-OUT Bogo, Carlos P. Garcia, Bohol Bogo Seaweed Growers Association 15 37,500.00 SEAWEED GROW-OUT Campamanog, Carlos P. Garcia, Bohol Campamanog Fishermen's Association 15 37,500.00 SEAWEED GROW-OUT Hingotanan East, Bien Unido, Bohol Hingotanan East Seaweed Growers Association 15 37,500.00 SEAWEED GROW-OUT Guindacpan, Tubigon, Bohol Guindacpan Seaweed Growers Association 15 37,500.00 SEAWEED GROW-OUT Dipatlog, Maribojoc, Bohol Maribojoc Seaweed Growers Association 15 37,500.00 SEAWEED GROW-OUT Lagtangon, Maribojoc, Bohol Lagtangon Seaweed Growers Association 15 37,500.00 SEAWEED SEEDLINGS DISTRIBUTION Busalian, Talibon, Bohol Busalian Agriculture Fishery Dev't. Association 15 37,500.00 SEAWEED SEEDLINGS DISTRIBUTION Kahayag, Lawis, Calape, Bohol Kahayag Fisherfolk Association 15 37,500.00 SEAWEED SEEDLINGS DISTRIBUTION Campao Occ., Calape, Bohol Campao Occ. Seaweed Farmers Association 15 37,500.00 SEAWEED SEEDLINGS DISTRIBUTION Tintinan, Ubay, Bohol Tintinan Fisherfolk -

A Comprehensive Assessment of the Agricultural Extension System in the Philippines: Case Study of LGU Extension in Ubay, Bohol

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Saz, Efren B. Working Paper A Comprehensive Assessment of the Agricultural Extension System in the Philippines: Case Study of LGU Extension in Ubay, Bohol PIDS Discussion Paper Series, No. 2007-02 Provided in Cooperation with: Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), Philippines Suggested Citation: Saz, Efren B. (2007) : A Comprehensive Assessment of the Agricultural Extension System in the Philippines: Case Study of LGU Extension in Ubay, Bohol, PIDS Discussion Paper Series, No. 2007-02, Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), Makati City This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/127938 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Philippine Institute for Development Studies Surian sa mga Pag-aaral Pangkaunlaran ng Pilipinas A Comprehensive Assessment of the Agricultural Extension System in the Philippines: Case Study of LGU Extension in Ubay, Bohol Efren B. -

Cy 2010 Internal Revenue Allotment for Barangays Region Vii Province of Bohol

CY 2010 INTERNAL REVENUE ALLOTMENT FOR BARANGAYS REGION VII PROVINCE OF BOHOL COMPUTATION OF THE CY 2010 INTERNAL REVENUE ALLOTMENT BARANGAY CY 2007 P80,000 CENSUS FOR BRGYS. SHARE EQUAL TOTAL POPULATION W/ 100 OR MORE BASED ON SHARING (ROUNDED) POPULATION POPULATION MUN. OF ALBURQUERQUE 1 Bahi 807 80,000.00 266,647.24 463,312.44 809,960.00 2 Basacdacu 793 80,000.00 262,021.39 463,312.44 805,334.00 3 Cantiguib 571 80,000.00 188,668.61 463,312.44 731,981.00 4 Dangay 809 80,000.00 267,308.07 463,312.44 810,621.00 5 East Poblacion 1,744 80,000.00 576,248.80 463,312.44 1,119,561.00 6 Ponong 1,021 80,000.00 337,356.66 463,312.44 880,669.00 7 San Agustin 515 80,000.00 170,165.21 463,312.44 713,478.00 8 Santa Filomena 828 80,000.00 273,586.01 463,312.44 816,898.00 9 Tagbuane 836 80,000.00 276,229.36 463,312.44 819,542.00 10 Toril 703 80,000.00 232,283.78 463,312.44 775,596.00 11 West Poblacion 1,017 80,000.00 336,034.99 463,312.44 879,347.00 ------------------------ ------------------------- ----------------------------------------------------- -------------------------- Total 9,644 880,000.00 3,186,550.12 5,096,436.87 9,162,987.00 ============= ============== =============== =============== ============== MUN. OF ALICIA 1 Cabatang 639 80,000.00 211,137.03 463,312.44 754,449.00 2 Cagongcagong 479 80,000.00 158,270.17 463,312.44 701,583.00 3 Cambaol 1,253 80,000.00 414,013.62 463,312.44 957,326.00 4 Cayacay 1,797 80,000.00 593,760.95 463,312.44 1,137,073.00 5 Del Monte 793 80,000.00 262,021.39 463,312.44 805,334.00 6 Katipunan 2,582 80,000.00 -

Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH)

nr' Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) Contract ID : 2OHBO169 Contract Name : Concreting of Sitio Tawid, Brgy. Mayuga to Brgy. Biabas FMR, Mayuga and Brgy. Biabas, Guindulman, Bohol Sta. 0+954.55 - Sta. 1+O5a.OO; Sta. 1+a4O.00 - Sta. 1+943.46; Sta. 2+082.15 - Sta.2+252.81i Sta,2+637.a1 - Sta.2+808.27 Locatlon of Contract: Brgy, Mayuga and Brgy. Biabas, Guindulman, Bohol Department of Public Works and Highways Bohol 3d District Engineering Office Guindulman, Bohol BAC RESOLTJTION DECLARING THE BIDDER WITH THE SINGLE CALCULATED RESPONSIVE BID AND RECOMMENDING AWARD THERETO RESoLUTION NO. 8!69-:-2029 WHEREAS, the Department of Public Works and Highways, Bohol 3rd District Engineering Office, Guindulman, Bohol, advertised the Invitation to Apply for Eligibility and to Bid for the above-stated contract in the Ph|IGEPS on July 21, 2o2o and posted the same at the DPWH website and in the coflspi€uous place at the premises of DPWH_Bohol 3d District Engineering Office continuously for 7 days starting on July 21,2020; WHEREAS. in response to the said Invitation, only One (1) contractor purchased Bidding Documents and both were found eligible; WHEREAS, the BAC received One (1) bid forthe Contract on August 10, 2o2o when the bid was opened, the following bid as read passed the preliminary examination: Total Bid amount Name of Bidd€r As Read (Php) trom aBc NN YU CONSTRUCTION INC. 11,565 ,479 .18 3.740/o WHEREAS, the detailed evaluation of bid conducted on August 12, 2020 resulted in the following bid as calculated: Total Bid amount as carcurated (PhP) from ABC NN YU CONSTRUCTION INC, 17,464,91A.78 3.944/o WHEREAS, pursuant to the provision of RA 9184 Section (36a) - Single Calculated/Rated and Responsive Bid Submission.