Saskatchewan)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saskatchewan Intraprovincial Miles

GREYHOUND CANADA PASSENGER FARE TARIFF AND SALES MANUAL GREYHOUND CANADA TRANSPORTATION ULC. SASKATCHEWAN INTRA-PROVINCIAL MILES The miles shown in Section 9 are to be used in connection with the Mileage Fare Tables in Section 6 of this Manual. If through miles between origin and destination are not published, miles will be constructed via the route traveled, using miles in Section 9. Section 9 is divided into 8 sections as follows: Section 9 Inter-Provincial Mileage Section 9ab Alberta Intra-Provincial Mileage Section 9bc British Columbia Intra-Provincial Mileage Section 9mb Manitoba Intra-Provincial Mileage Section9on Ontario Intra-Provincial Mileage Section 9pq Quebec Intra-Provincial Mileage Section 9sk Saskatchewan Intra-Provincial Mileage Section 9yt Yukon Territory Intra-Provincial Mileage NOTE: Always quote and sell the lowest applicable fare to the passenger. Please check Section 7 - PROMOTIONAL FARES and Section 8 – CITY SPECIFIC REDUCED FARES first, for any promotional or reduced fares in effect that might result in a lower fare for the passenger. If there are none, then determine the miles and apply miles to the appropriate fare table. Tuesday, July 02, 2013 Page 9sk.1 of 29 GREYHOUND CANADA PASSENGER FARE TARIFF AND SALES MANUAL GREYHOUND CANADA TRANSPORTATION ULC. SASKATCHEWAN INTRA-PROVINCIAL MILES City Prv Miles City Prv Miles City Prv Miles BETWEEN ABBEY SK AND BETWEEN ALIDA SK AND BETWEEN ANEROID SK AND LANCER SK 8 STORTHOAKS SK 10 EASTEND SK 82 SHACKLETON SK 8 BETWEEN ALLAN SK AND HAZENMORE SK 8 SWIFT CURRENT SK 62 BETHUNE -

Saskatchewan Regional Newcomer Gateways

Saskatchewan Regional Newcomer Gateways Updated September 2011 Meadow Lake Big River Candle Lake St. Walburg Spiritwood Prince Nipawin Lloydminster wo Albert Carrot River Lashburn Shellbrook Birch Hills Maidstone L Melfort Hudson Bay Blaine Lake Kinistino Cut Knife North Duck ef Lake Wakaw Tisdale Unity Battleford Rosthern Cudworth Naicam Macklin Macklin Wilkie Humboldt Kelvington BiggarB Asquith Saskatoonn Watson Wadena N LuselandL Delisle Preeceville Allan Lanigan Foam Lake Dundurn Wynyard Canora Watrous Kindersley Rosetown Outlook Davidson Alsask Ituna Yorkton Legend Elrose Southey Cupar Regional FortAppelle Qu’Appelle Melville Newcomer Lumsden Esterhazy Indian Head Gateways Swift oo Herbert Caronport a Current Grenfell Communities Pense Regina Served Gull Lake Moose Moosomin Milestone Kipling (not all listed) Gravelbourg Jaw Maple Creek Wawota Routes Ponteix Weyburn Shaunavon Assiniboia Radwille Carlyle Oxbow Coronachc Regway Estevan Southeast Regional College 255 Spruce Drive Estevan Estevan SK S4A 2V6 Phone: (306) 637-4920 Southeast Newcomer Services Fax: (306) 634-8060 Email: [email protected] Website: www.southeastnewcomer.com Alameda Gainsborough Minton Alida Gladmar North Portal Antler Glen Ewen North Weyburn Arcola Goodwater Oungre Beaubier Griffin Oxbow Bellegarde Halbrite Radville Benson Hazelwood Redvers Bienfait Heward Roche Percee Cannington Lake Kennedy Storthoaks Carievale Kenosee Lake Stoughton Carlyle Kipling Torquay Carnduff Kisbey Tribune Coalfields Lake Alma Trossachs Creelman Lampman Walpole Estevan -

Saskatchewan

1 SASKATCHEWAN BREEDER LOCATION PROVINCE PHONE 2020 WHE NUMBER TOTAL 7 PILLARS RANCH LTD SHELL LAKE SK 306-427-0051 191 ALLANVILLE FARMS LTD TISDALE SK 306-873-5288 92 AM SUNRISE FARM BATTLEFORD SK 306-441-6865 46 ANGLE H STOCK FARM DEBDEN SK 306-724-4907 33 BAR "H" CHAROLAIS GRENFELL SK 306-697-2901 65 BECK FARMS LANG SK 306-436-7458 203 BLUE SKY CHAROLAIS GULL LAKE SK 306-672-4217 86 BORDERLAND CATTLE COMPANY ROCKGLEN SK 306-476-2439 82 BOX J RANCH COCHIN SK 306-386-2728 59 BRICNEY STOCK FARM LTD. MAIDSTONE SK 306-893-4510 75 BRIMNER CATTLE CO. MANOR SK 306-448-2028 95 CAMPBELLS CHAROLAIS GRIFFIN SK 306-842-6231 28 CASBAR FARMS BLAINE LAKE SK 306-497-2265 75 CAY'S CATTLE KINISTINO SK 306-864-7307 16 CEDARLEA FARMS HODGEVILLE SK 306-677-2589 226 CHARBURG CHAROLAIS BETHUNE SK 3 CHARRED CREEK RANCH WEYBURN SK 306-842-2846 3 CHARROW CHAROLAIS MARSHALL SK 306-307-6073 57 CHARTOP CHAROLAIS GULL LAKE SK 306-672-3979 38 CK SPARROW FARMS LTD VANSCOY SK 306-668-4218 183 CK STOCK FARMS CANDIAC SK 306-736-9666 20 CRAIG CHAROLAIS MOSSBANK SK 306-354-7431 19 CREEK'S EDGE LAND & CATTLE YELLOW CREEK SK 306-279-2033 189 CSS CHAROLAIS PAYNTON SK 306-895-4316 29 DIAMOND R STOCK FARMS WAWOTA SK 306-739-2781 15 DIAMOND W CHAROLAIS HUDSON BAY SK 306-865-3953 119 DM LIVESTOCK CARROT RIVER SK 306-768-3605 23 DOGPATCH ACRES LEROY SK 306-287-4008 92 BRAD & SCHUYLER EDISON WYNYARD SK 306-554-7406 9 CHANCE EISERMAN MAPLE CREEK SK 306-558-4509 1 ELDER CHAROLAIS FARM CORONACH SK 306-267-4986 148 FERN CREEK CHAROLAIS LOVE SK 306-276-5976 1 FLAT-TOP CATTLE CO. -

April 9Th DELIVERY SCHEDULE March 22Nd

STEVEN JOHN DELIVERY SCHEDULE JOJIT March 22nd - March 26th Monday (22) Tuesday (23) Wednesday (24) Thursday (25) Friday (26) Lloydminster Spiritwood Luseland Meadow Lake Kindersley Wilkie Lloydminster Marshall Glaslyn Dodsland Coleville Unity Marshall Paynton Medstead Plenty Smiley * Sweetgrass Paynton Maidstone Cochin Kerrobert Marengo * Poundmaker Maidstone Lashburn Saulteaux Mosquito Cut Knife Lashburn Onion Lake Moosomin Red Pheasant Little Pine Leoville Denzil Marsden Meota Neilburg Shell Lake March 29 - April 2nd Monday (29) Tuesday (30) Wednesday (31) Thursday (1) Friday (2) Lloydminster Turtleford Maymont Meadow Lake Kindersley Wilkie C Marshall Edam Hafford Biggar Coleville Unity L Paynton St.Walburg Radisson Rosetown Smiley * Landis O Maidstone Meota Fiske Marengo * Macklin S Lashburn Paradise Hill Perdue E Onion Lake Mervin D'arcy D Thunderchild Cando Loon Lkae Harris * Pierceland Goodsil April 5th - April 9th Monday (5) Tuesday (6) Wednesday (7) Thursday (8) Friday (9) Lloydminster Spiritwood Luseland Meadow Lake Kindersley Wilkie Lloydminster Marshall Glaslyn Dodsland Coleville Unity Marshall Paynton Medstead Plenty Smiley * Sweetgrass Maidstone Cochin Kerrobert Marengo * Poundmaker Lashburn Saulteaux Mosquito Cut Knife Onion Lake Moosomin Red Pheasant Little Pine Leoville Denzil Marsden Meota Neilburg Shell Lake April 12th - April 16th Monday (12) Tuesday (13) Wednesday (14) Thursday (15) Friday (16) Lloydminster Turtleford Hafford Meadow Lake Kindersley Wilkie Lloydminster Marshall Edam Maymont Biggar Coleville Unity Kyle Paynton St.Walburg Radisson Rosetown Smiley * Landis Beechy Maidstone Meota Fiske Marengo * Macklin Lucky Lake Lashburn Paradise Hill Perdue Dinsmore Onion Lake Mervin D'arcy Delisle Thunderchild Cando Outlook Harris *. -

Diabetes Directory

Saskatchewan Diabetes Directory February 2015 A Directory of Diabetes Services and Contacts in Saskatchewan This Directory will help health care providers and the general public find diabetes contacts in each health region as well as in First Nations communities. The information in the Directory will be of value to new or long-term Saskatchewan residents who need to find out about diabetes services and resources, or health care providers looking for contact information for a client or for themselves. If you find information in the directory that needs to be corrected or edited, contact: Primary Health Services Branch Phone: (306) 787-0889 Fax : (306) 787-0890 E-mail: [email protected] Acknowledgement The Saskatchewan Ministry of Health acknowledges the efforts/work/contribution of the Saskatoon Health Region staff in compiling the Saskatchewan Diabetes Directory. www.saskatchewan.ca/live/health-and-healthy-living/health-topics-awareness-and- prevention/diseases-and-disorders/diabetes Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................... - 1 - SASKATCHEWAN HEALTH REGIONS MAP ............................................. - 3 - WHAT HEALTH REGION IS YOUR COMMUNITY IN? ................................................................................... - 3 - ATHABASCA HEALTH AUTHORITY ....................................................... - 4 - MAP ............................................................................................................................................... -

Saskatchewan Conference Prayer Cycle

July 2 September 10 Carnduff Alida TV Saskatoon: Grace Westminster RB The Faith Formation Network hopes that Clavet RB Grenfell TV congregations and individuals will use this Coteau Hills (Beechy, Birsay, Gull Lake: Knox CH prayer cycle as a way to connect with other Lucky Lake) PP Regina: Heritage WA pastoral charges and ministries by including July 9 Ituna: Lakeside GS them in our weekly thoughts and prayers. Colleston, Steep Creek TA September 17 Craik (Craik, Holdfast, Penzance) WA Your local care facilities Take note of when your own pastoral July 16 Saskatoon: Grosvenor Park RB charge or ministry is included and remem- Colonsay RB Hudson Bay Larger Parish ber on that day the many others who are Crossroads (Govan, Semans, (Hudson Bay, Prairie River) TA holding you in their prayers. Raymore) GS Indian Head: St. Andrew’s TV Saskatchewan Crystal Springs TA Kamsack: Westminister GS This prayer cycle begins a week after July 23 September 24 Thanksgiving this year and ends the week Conference Spiritual Care Educator, Humboldt (Brithdir, Humboldt) RB of Thanksgiving in 2017. St. Paul’s Hospital RB Kelliher: St. Paul GS Prayer Cycle Crossroads United (Maryfield, Kennedy (Kennedy, Langbank) TV Every Pastoral Charge and Special Ministry Wawota) TV Kerrobert PP in Saskatchewan Conference has been 2016—2017 Cut Knife PP October 1 listed once in this one year prayer cycle. Davidson-Girvin RB Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women Sponsored by July 30 Imperial RB The Saskatchewan Conference Delisle—Vanscoy RB KeLRose GS Eatonia-Mantario PP Kindersley: St. Paul’s PP Faith Formation Network Earl Grey WA October 8 Edgeley GS Kinistino TA August 6 Kipling TV Dundurn, Hanley RB Saskatoon: Knox RB Regina: Eastside WA Regina: Knox Metropolitan WA Esterhazy: St. -

Charitable Gaming Grants Paid by Community April 1, 2019 to June 30, 2019

Charitable Gaming Grants Paid by Community April 1, 2019 to June 30, 2019 Community Name Charity Name Grant Amount Abbey Abbey Business and Community Centre $ 386.25 Abbey Total $ 386.25 Aberdeen Aberdeen & District Culture and Recreation Board $ 1,529.68 Aberdeen Aberdeen Composite School SRC $ 348.00 Aberdeen Aberdeen Creative Preschool $ 825.00 Aberdeen Aberdeen Flames Pee Wee Team $ 292.50 Aberdeen Aberdeen Minor Hockey Association $ 1,233.95 Aberdeen Aberdeen Novice Flames Hockey $ 378.75 Aberdeen Aberdeen School Community Council $ 336.00 Aberdeen Dance Aberdeen $ 500.00 Aberdeen Total $ 5,443.88 Alameda Alameda Recreational Board Inc. $ 4,146.25 Alameda Total $ 4,146.25 Alida Alida Recreation Hall and Rink Board $ 970.42 Alida Total $ 970.42 Alvena Alvena Community Center $ 1,102.72 Alvena Total $ 1,102.72 Annaheim Annaheim Recreation Board $ 1,260.50 Annaheim Total $ 1,260.50 Arborfield Preeceville Figure Skating Club $ 562.50 Arborfield Total $ 562.50 Arcola Arcola Daycare Inc. $ 1,210.19 Arcola Prairie Place Complex $ 676.25 Arcola Total $ 1,886.44 Asquith Better Life Recreation Association $ 47.75 Asquith Saskatoon Laser U16A $ 587.53 Asquith Total $ 635.28 Assiniboia Assiniboia 55 Club Inc. $ 290.26 Assiniboia Assiniboia Kinsmen Club $ 952.50 Assiniboia Southern Rebels Junior B Hockey Club $ 8,156.53 Assiniboia Total $ 9,399.29 Avonlea Dirt Hills Wildlife Federation $ 593.53 Avonlea Total $ 593.53 Balcarres Balcarres & District Lions Club $ 713.75 Balcarres Balcarres Centennial Rink Board $ 1,605.33 Balcarres Total $ 2,319.08 Balgonie Balgonie B.P.O. Elks Lodge #572 $ 268.88 Balgonie Balgonie Early Learning Centre Inc. -

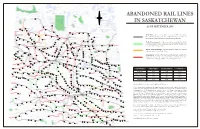

Abandoned Rail Lines in Saskatchewan

N ABANDONED RAIL LINES W E Meadow Lake IN SASKATCHEWAN S Big River Chitek Lake AS OF SEPTEMBER 2008 Frenchman Butte St. Walburg Leoville Paradise Hill Spruce Lake Debden Paddockwood Smeaton Choiceland Turtleford White Fox LLYODMINISTER Mervin Glaslyn Spiritwood Meath Park Canwood Nipawin In-Service: rail line that is still in service with a Class 1 or short- Shell Lake Medstead Marshall PRINCE ALBERT line railroad company, and for which no notice of intent to Edam Carrot River Lashburn discontinue has been entered on the railroad’s 3-year plan. Rabbit Lake Shellbrooke Maidstone Vawn Aylsham Lone Rock Parkside Gronlid Arborfield Paynton Ridgedale Meota Leask Zenon Park Macdowell Weldon To Be Discontinued: rail line currently in-service but for which Prince Birch Hills Neilburg Delmas Marcelin Hagen a notice of intent to discontinue has been entered in the railroad’s St. Louis Prairie River Erwood Star City NORTH BATTLEFORD Hoey Crooked River Hudson Bay current published 3-year plan. Krydor Blaine Lake Duck Lake Tisdale Domremy Crystal Springs MELFORT Cutknife Battleford Tway Bjorkdale Rockhaven Hafford Yellow Creek Speers Laird Sylvania Richard Pathlow Clemenceau Denholm Rosthern Recent Discontinuance: rail line which has been discontinued Rudell Wakaw St. Brieux Waldheim Porcupine Plain Maymont Pleasantdale Weekes within the past 3 years (2006 - 2008). Senlac St. Benedict Adanac Hepburn Hague Unity Radisson Cudworth Lac Vert Evesham Wilkie Middle Lake Macklin Neuanlage Archerwill Borden Naicam Cando Pilger Scott Lake Lenore Abandoned: rail line which has been discontinued / abandoned Primate Osler Reward Dalmeny Prud’homme Denzil Langham Spalding longer than 3 years ago. Note that in some cases the lines were Arelee Warman Vonda Bruno Rose Valley Salvador Usherville Landis Humbolt abandoned decades ago; rail beds may no longer be intact. -

Annual Report

Annual Report 2014 1302-—1oothStreet North Battleford, SK S9A 0V8 Phone: 306-445-6108 Email: [email protected] Lakeland Library Region Legend —-— Library Region ? Regional Office m Public Library " "VP;rgaiseHill in Highway First Nation Land RM mRz;b7bitk|/.ak"e‘ [ , , \,\j?LNorihBattleforgx V Chairperson’s Report 2014 was a year of many changes at Lakeland Library Region. We had staff turnover in many of the rural branches, resource libraries and at Headquarters. Interim Director, Donna Challis, retired after more than 5 years of leading the Region. Her impact will continue to be felt for years to come as the Region builds on the foundation that she established. Eleanor Crumblehulme, previously the Regional Librarian, took over as the Director in November. Throughout these changes, the Region remained stable, efficient, and continued to offer high-quality library services. Circulation was up in some branches and down in others, but the regional total (412,705) was steady, down only 0.2% from 2013. Overall, our circulation figures have increased over the last 4 years. Additionally, library2go (eBooks and eAudiobooks) was used more than ever before, with a total of 49,168 circulations in 2014 — an increase of 29% over 2013. Public Access Computer uses were also up quite a bit, increasing 12% to 17,001. Participation in the TD Summer Reading Club (SRC) was down this year, but the Lakeland Summer Players had a very successful run. Noah Cooke and Andrea Hernando gave 22 performances (18 at branches and 4 at Summer Literacy Camps) for a total of 472 people. -

Delivery Schedule

STEVEN JOHN DELIVERY SCHEDULE JOJIT November 1st - November 7th Monday (2) Tuesday (3) Wednesday (4) Thursday (5) Friday (6) Lloydminster Loon Lake Maymont Meadow Lake Kindersley Wilkie Lloydminster Marshall Goodsoil Hafford Biggar Coleville Unity Marshall Paynton Pierceland Radisson Rosetown Marengo Landis Paynton Maidstone St. Walburg Fiske Smiley Macklin Maidstone Lashburn Turtleford Perdue Lashburn Onion Lake Paradise Hill D'arcy Edam Meota November 8th - November 14th Monday (9) Tuesday (10) Wednesday (11) Thursday (12) Friday (13) Lloydminster Spiritwood Luseland Kindersley Cut Knife Lloydminster Marshall Glaslyn Dodsland C Coleville Little Pine Kyle Paynton Medstead Plenty L Marsden Beechy Maidstone Cochin Kerrobert O Neilburg Lucky Lake Lashburn Saulteaux Mosquito S Poundmaker Milden Onion Lake Moosomin Red Pheasant E Sweetgrass Dinsmore Leoville Denzil D Wilkie Delisle Shell Lake Unity Outlook Meota November 15th - November 21st Monday (16) Tuesday (17) Wednesday (18) Thursday (19) Friday (20) Lloydminster Turtleford Maymont Meadow Lake Kindersley Wilkie Lloydminster Marshall Edam Hafford Biggar Coleville Unity Marshall Paynton St.Walburg Radisson Rosetown Marengo Landis Paynton Maidstone Meota Fiske Smiley Macklin Maidstone Lashburn Paradise Hill Perdue Lashburn Onion Lake Mervin D'arcy Thunderchild November 22nd - November 28th Monday (23) Tuesday (24) Wednesday (25) Thursday (26) Friday (27) Lloydminster Spiritwood Luseland Meadow Lake Kindersley Cut Knife Lloydminster Marshall Glaslyn Dodsland Biggar Coleville Little Pine Marshall Paynton Medstead Plenty Rosetown Marsden Paynton Maidstone Cochin Kerrobert Fiske Neilburg Maidstone Lashburn Saulteaux Mosquito Perdue Poundmaker Lashburn Onion Lake Moosomin Red Pheasant D'arcy Sweetgrass Eston Leoville Denzil Cando Wilkie Elrose Shell Lake Unity Eatonia Meota. -

Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), Formerly Known As Lloydminster the North West Mounted Police 16 Paynton

1-877-2ESCAPE | www.sasktourism.com Travel Itinerary | trail of the mounties To access online maps of Saskatchewan or to request a Saskatchewan Discovery Guide and Official Highway Map, visit: www.sasktourism.com/travel-information/travel-guides-and-maps Trip Length 4-5 days trail of the mounties 1310 km RCMP Sunset Retreat Ceremony, Regina. Tourism Saskatchewan/Hans-Gerhard Pfaffer Saskatoon Regina • Itinerary Route • Alternate Route The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), formerly known as Lloydminster the North West Mounted Police 16 Paynton Little Pine (NWMP), are Canada’s national 674 Poundmaker North Battleford Cut Knife 40 police force and one of the most Fort Battleford National Historic Site A T 16 respected and well-known law- ALBER enforcement agencies in the world. Biggar Nothing quite says Canada like the image of Mounties clad in the Force’s traditional scarlet tunic, and no other place in the country 4 Saskatoon 31 has closer ties to the RCMP than Saskatchewan. Starting in Regina, Herschel Regina Rosetown this five day driving tour takes you to four of Saskatchewan’s, and indeed Canada’s, most significant RCMP sites. SASKATCHEWAN South Saskatchewan River DAY ONE Regina Sask Landing Provincial Park Lake Diefenbaker Regina A visit to Regina’s RCMP Heritage Centre is the perfect place to start 4 Moose Jaw 1 – a fascinating look at the world-famous police force through exhibits, Swift Current multi-media presentations and on-site interpretation. The building 1 2 1 is impressive in its own right, a unique and environmentally-friendly Maple Creek Cypress Hills stone, glass and concrete structure designed by famous architect Lloydminster Winery 271 Cypress Hills Interprovincial Park Arthur Erickson. -

Lakeland Library Region Annual Report 2013

Lakeland Library Region Annual Report 2013 LAKELAND LIBRARY REGION—1302-100TH STREET. NORTH BATTLEFORD. SK. S9A 0V8 306-445-6108 (PHONE) 306-445-5717 (FAX) Like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter LAKELAND LIBRARY REGION – CHAIRS REPORT 2013 was a fairly stable year for the region, with circulation remaining solid, the introduction to some new services like ZINIO and TUMBLEBOOKS, as well as significant increases in Library2go stats. Which leaves me agree with an article from Devin Coldewey of NBC News. E-Books surge as devices multiply -- but print holds fast. We also had another good increase in active patrons during 2013 and the drive to get more people carrying and using library cards will continue. Lakeland Library Region continues to strengthen our Early Childhood collection with the development in 2013 of many new kits, including ABC, Color and Numbers. Also developed were activities ideas for all seasons, all celebrations and occasions. The number of new pre-packaged puppet shows for story time activities have been put together, all in an effort to help the smaller libraries and schools in our region with the ability to provide learning and programming sessions without having to prepare everything themselves. Two aboriginal kits have been developed that we hope will become very useful in our storytelling and cultural activities during several occasions during the year. Lakeland continues to use social media --- Facebook, Twitter to get our word out and headquarters staff provides branches with other sources like websites and blogs containing great programming, promotion and display ideas. All of these resources can easily be found on the staff side of the web page or in our newsletters.