Feasibility Study of Trenton, New Jersey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021 SWB Railriders Media Guide

2021 swb railriders 2021 swb railriders triple-a information On February 12, 2021, Major League Baseball announced its new plan for affiliated baseball, with 120 Minor League clubs officially agreeing to join the new Professional Development League (PDL). In total, the new player development system includes 179 teams across 17 leagues in 43 states and four provinces. Including the AZL and GCL, there are 209 teams across 19 leagues in 44 states and four provinces. That includes the 150 teams in the PDL and AZL/GCL along with the four partner leagues: the American Association, Atlantic League, Frontier League and Pioneer League. The long-time Triple-A structure of the International and Pacific Coast Leagues have been replaced by Triple-A East and Triple-A West. Triple-A East consists on 20 teams; all 14 from the International League, plus teams moving from the Pacific Coast League, the Southern League and the independent Atlantic League. Triple-A West is comprised of nine Pacific Coast League teams and one addition from the Atlantic League. These changes were made to help reduce travel and allow Major League teams to have their affiliates, in most cases, within 200 miles of the parent club (or play at their Spring Training facilities). triple-a clubs & affiliates midwest northeast southeast e Columbus (Cleveland Indians) Buffalo (Toronto Blue Jays) Charlotte (Chicago White Sox) Indianapolis (Pittsburgh Pirates) Lehigh Valley (Philadelphia Phillies) Durham (Tampa Bay Rays) a Iowa (Chicago Cubs) Rochester (Washington Nationals) Gwinnett (Atlanta Braves) s Louisville (Cincinnati Reds) Scranton/ Wilkes-Barre (New York Yankees) Jacksonville (Miami Marlins) Omaha (Kansas City Royals) Syracuse (New York Mets) Memphis (St. -

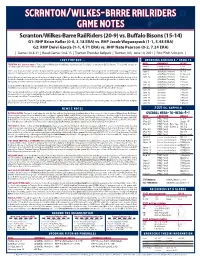

Scranton/Wilkes-Barre Railriders Game Notes Scranton/Wilkes-Barre Railriders (20-9) Vs

scranton/wilkes-barre railriders game notes Scranton/Wilkes-Barre RailRiders (20-9) vs. Buffalo Bisons (15-14) G1: RHP Brian Keller (0-0, 3.18 ERA) vs. RHP Jacob Waguespack (1-1, 5.48 ERA) G2: RHP Deivi García (1-1, 4.71 ERA) vs. RHP Nate Pearson (0-2, 7.24 ERA) | Games 30 & 31 | Road Games 14 & 15 | Trenton Thunder Ballpark | Trenton, NJ | June 10, 2021 | First Pitch 5:00 p.m. | last time out... upcoming schedule / results TRENTON, N.J. (June 8, 2021) – The Scranton/Wilkes-Barre RailRiders erased an early 5-0 deficit to defeat the Buffalo Bisons 7-5 in a wild contest on date opponent result Tuesday night at Trenton Thunder Ballpark. June 5 Lehigh Valley L, 9-6 June 6 Lehigh Valley W, 4-3 After a one-hour, 45-minute weather delay to start the game, Zack Britton got the start in an MLB rehab assignment. The left-hander was tagged for four June 8 @ Buffalo (Trenton) W, 7-5 runs in 0.1 innings of work. He allowed a two-run double to Tyler White and a two-run home run to Jared Hoying to stake Buffalo to an early 4-0 lead. June 9 @ Buffalo (Trenton) Postponed Adam Warren allowed one run in 2.2 innings of relief in back of Britton, but the Bisons maintained a 5-0 advantage after the third. In the top of the June 10 @ Buffalo (Trenton) 5:00 p.m. fourth the RailRiders struck for three runs against Anthony Kay. Derek Dietrich drove home Hoy Park with an RBI single, and three batters later, Andrew @ Buffalo (Trenton) Game 2 Velazquez provided a two-run single to narrow the gap to 5-3. -

Portland Sea Dogs 2018 Media Guide

Portland Sea Dogs 2018 Media Guide DOUBLE-A AFFILIATE OF THE BOSTON RED SOX TABLEP AGEOF CTONITLETENTS Portland2018 SHEDULE Sea Dogs Arlsun mon tue wed thu fri sat Masun mon tue wed thu fri sat 1 2 3 4 bi 5 bi 6 bi 7 tr 1 tr 2 hf 3 hf 4 hf 5 6:35 7:05 3:05 FIREWORKS MAY 25 6:00 6:00 7:05 7:05 6:05 bi 8 re 9 re 10 re 11 12 bi 13 bi 14 hf 6 nh 7 nh 8 nh 9 bi 10 bi 11 bi 12 2:05 6:35 6:35 1:05 6:00 1:00 1:05 6:35 6:35 6:35 6:00 6:00 1:00 bi 15 HF 16 HF 17 HF 18 HF 19 TR 20 TR 21 bi 13 re 14 re 15 re 16 al 17 al 18 al 19 1:00 6:00 6:00 6:00 12:00 7:00 1:00 1:00 6:35 11:35 11:35 6:00 6:00 6:00 TR 22 HF 23 HF 24 HF 25 26 RE 27 RE 28 al 20 21 hf 22 hf 23 hf 24 re 25 re 26 1:00 7:05 7:05 7:05 6:00 1:00 2:00 6:00 6:00 11:00 6:00 1:00 RE 29 TR 30 re 27 re 28 nh 29 nh 30 nh 31 1:00 6:00 1:00 1:00 6:35 6:35 11:35 nesun mon tue wed thu fri sat lysun mon tue wed thu fri sat hb 1 hb 2 bi 1 bi 2 bi 3 hf 4 hf 5 hf 6 hf 7 FIREWORKS JUNE 21 7:00 6:00 1:00 7:00 6:00 4:05 7:05 7:05 6:05 hb 3 4 bo 5 bo 6 bo 7 ak 8 ak 9 hf 8 9 10 11 nh 12 nh 13 nh 14 3:30 7:00 7:00 11:00 7:00 6:00 1:05 llStar rea 7:00 7:00 6:00 ak 10 11 ri 12 ri 13 ri 14 bo 15 bo 16 nh 15 bi 16 bi 17 bi 18 hf 19 hf 20 hf 21 1:00 6:35 6:35 6:35 7:05 6:35 1:00 6:35 6:35 1:05 7:00 7:00 6:00 bo 17 18 re 19 re 20 re 21 tr 22 tr 23 hf 22 hb 23 hb 24 hb 25 tr 26 tr 27 tr 28 1:35 7:00 7:00 6:00 7:00 6:00 1:00 7:00 7:00 12:00 7:00 7:00 7:00 tr 24 nh 25 nh 26 nh 27 nh 28 bi 29 bi 30 tr 29 30 er 31 FIREWORKS JULY 3, 21 1:00 7:05 7:05 7:05 7:05 7:00 6:00 5:00 7:00 Agstsun mon tue wed thu fri sat Seteersun -

* Text Features

The Boston Red Sox Thursday, May 6, 2021 * The Boston Globe Red Sox left all wet, going from near walkoff to extra-inning loss vs. Tigers Alex Speier They did it again, or so it seemed for an instant. A Red Sox team that has made a habit of comeback victories in the first five weeks of 2021 seemed poised to conjure another. Down two against the Tigers in the bottom of the seventh, the team knotted the score on a J.D. Martinez two-run homer, then edged towards a walk-off triumph with a ninth-inning rally. With the bases loaded and two outs in the bottom of the ninth, Xander Bogaerts drilled a liner to left-center that seemed destined to kiss the Fenway turf and allow the Red Sox to dance onto the field. Instead, left fielder Robbie Grossman fought through raindrops and the lights, falling as he corralled the final out of the inning. Minutes later, the Tigers ambushed Red Sox reliever Garrett Whitlock for a three- run 10th, just enough to withstand a furious Red Sox rally in the bottom of the inning and hold on for a 6-5 victory. Though the Red Sox continue to occupy first place in the AL East, their current stretch represents a string of missed opportunities. The team has dropped four of six to the last-place Rangers and Tigers, the latter of whom snapped a six-game losing streak on Wednesday. ”We’re not invincible,” said starter Martín Pérez. “[But] we’re going to be fine. -

Scranton/Wilkes-Barre Railriders Game Notes Syracuse Mets (11-25) Vs

scranton/wilkes-barre railriders game notes Syracuse Mets (11-25) vs. Scranton/Wilkes-Barre RailRiders (23-11) RHP Akeem Bostick (0-1, 11.81 ERA) vs. RHP Deivi García (1-2, 6.26 ERA) | Game 35 | Home Game 17 | PNC Field | Moosic, PA | June 15, 2021 | First Pitch 7:05 p.m. | last time out... upcoming schedule / results TRENTON, N.J. (June 13, 2021) – A six-run eruption in the top of the fourth inning and a combined shutout by five pitchers led the Scranton/ date opponent result Wilkes-Barre RailRiders to an 8-0 win over the Buffalo Bisons on Sunday at Trenton Thunder Ballpark. Luke Voit went 1-for-3 with a double and June 11 @ Buffalo (Trenton) L, 4-2 an RBI in the first game of his MLB rehab assignment, playing five innings at first base. June 12 @ Buffalo (Trenton) W, 6-4 (10) June 13 @ Buffalo (Trenton) W, 8-0 The game remained scoreless into the top of the fourth, but the Scranton/Wilkes-Barre offense broke through against Anthony Kay (0-2), touching June 15 Syracuse 7:05 p.m. up the left-hander for six runs. Trey Amburgey kicked off the frenzy with a double and scored on a single by Estevan Florial. The RailRiders also June 15 Syracuse 7:05 p.m. benefitted from a three-run home run by Derek Dietrich and RBI doubles from Voit and Ryan LaMarre in the frame. June 17 Syracuse 7:05 p.m. Amburgey finished the game 1-for-4 with a double and a run scored to stretch his season-long hitting streak to 18 games, the longest in Triple-A June 18 Syracuse 7:05 p.m. -

Scranton/Wilkes-Barre Railriders Game Notes Scranton/Wilkes-Barre Railriders (19-9) Vs

scranton/wilkes-barre railriders game notes Scranton/Wilkes-Barre RailRiders (19-9) vs. Buffalo Bisons (15-13) RHP Adam Warren (2-0, 2.70 ERA) vs. LHP Anthony Kay (0-0, 10.80 ERA) | Game 29 | Road Game 13 | Trenton Thunder Ballpark | Trenton, NJ | June 8, 2021 | First Pitch 7:00 p.m. | last time out... upcoming schedule / results MOOSIC, Pa. (June 6, 2021) – Early offense and a season-high 15 strikeouts by the pitching staff lifted the Scranton/Wilkes-Barre RailRiders to a 4-3 date opponent result victory over the Lehigh Valley IronPigs on Sunday at PNC Field. June 4 Lehigh Valley L, 5-4 June 5 Lehigh Valley L, 9-6 The RailRiders took the lead in the bottom of the first when a Trey Amburgey RBI double scored Hoy Park with the first run of the game. Scranton/ June 6 Lehigh Valley W, 4-3 Wilkes-Barre tacked on three more in the second, with an RBI double from Max McDowell and a two-run home run by Park highlighting the action. June 8 @ Buffalo (Trenton) 7:00 p.m. The long ball was the second in as many days for Park, and his fifth of the year in 15 games with the RailRiders. His career high for home runs in a June 9 @ Buffalo (Trenton) 7:00 p.m. season is seven in 2017. June 10 @ Buffalo (Trenton) 7:00 p.m. June 11 @ Buffalo (Trenton) 7:00 p.m. Staked to an early 4-0 lead, Nick Green turned in his best start of the season for SWB. -

Scranton/Wilkes-Barre Railriders Game Notes Scranton/Wilkes-Barre Railriders (21-11) Vs

scranton/wilkes-barre railriders game notes Scranton/Wilkes-Barre RailRiders (21-11) vs. Buffalo Bisons (17-15) RHP Nick Green (0-1, 5.66 ERA) vs. RHP T.J. Zeuch (1-3, 4.35 ERA) | Game 33 | Road Game 17 | Trenton Thunder Ballpark | Trenton, NJ | June 12, 2021 | First Pitch 6:30 p.m. | last time out... upcoming schedule / results TRENTON, N.J. (June 11, 2021) – The Scranton/Wilkes-Barre RailRiders fell to the Buffalo Bisons 4-2 on Friday night at Trenton Thunder Ballpark. date opponent result June 5 Lehigh Valley L, 9-6 Brody Koerner turned in a strong start for Scranton/Wilkes-Barre, allowing only one run on three hits in 4.0 innings of work. The right-hander walked June 6 Lehigh Valley W, 4-3 four and tied his season-high with five strikeouts. June 8 @ Buffalo (Trenton) W, 7-5 The lone run allowed by Koerner (1-3) came in the bottom of the fourth, when Cullen Large lifted a sacrifice fly to score Logan Warmoth. Buffalo June 9 @ Buffalo (Trenton) Postponed tacked on three runs in the sixth against Albert Abreu to extend its lead to 4-0. June 10 @ Buffalo (Trenton) - G1 W, 3-2 @ Buffalo (Trenton) - G2 L, 10-0 In the top of the seventh, Trey Amburgey led off with a solo home run off Nick Allgeyer to get the RailRiders on the board, but they still trailed 4-1. June 11 @ Buffalo (Trenton) L, 4-2 SWB loaded the bases with two outs in the eighth, but did not score. -

* Text Features

The Boston Red Sox Friday, May 7, 2021 * The Boston Globe Red Sox’ high-scoring win over Tigers shows how much work they need to do Julian McWilliams A four-run eighth inning saved the Red Sox from what would have been their worst series loss of the season Thursday, as they pulled out a 12-9 win over the Tigers at Fenway Park. The Tigers, the worst team in baseball, had the Red Sox on the ropes, leading, 9-8, in the bottom of the eighth. With Rafael Devers at first after reaching on an error, Detroit reliever Alex Lange fanned both Marwin Gonzalez and Hunter Renfroe. But after Kevin Plawecki negotiated a two-out walk, manager Alex Cora called on Christian Vázquez to pinch hit. Vázquez worked the count full, then he stung a 97-mile-per-hour heater down the third base line for a single that tied the game. The next batter, Franchy Cordero, hit a slow tapper that Tigers third baseman Jemeir Candelario couldn’t handle, allowing pinch runner Christian Arroyo to come home with the go-ahead run. A wild pitch moved the runners to second and third, and Alex Verdugo’s single up the middle scored them both. “It’s a big league win,” Cora said. “And you’ve got to take them. We have to address a lot of stuff. We know that we’ve been saying that over the course of the first month. And for us to get to where we want to go, we have to be a lot better. -

* Text Features

The Boston Red Sox Tuesday, May 4, 2021 * The Boston Globe Health has played critical role in hot Red Sox start Alex Speier While a tumble in Texas brought the first-place Red Sox back toward the AL East pack, in at least one respect, the team continues to enjoy a runaway advantage. One underappreciated aspect of the strong start is health. Outside of J.D. Martinez’s one day on the COVID-19 injury list, the team has had just three players on the IL since the start of this season: Chris Sale continues his rehab from his March 2020 Tommy John surgery, Ryan Brasier remains in Fort Myers to rehab his injured calf, and Eduardo Rodriguez missed one turn of the rotation due to dead arm at the start of the year. Entering Monday, the Sox had lost 71 player days to the non-COVID injured list, fifth fewest in the majors. Sale, of course, was never expected to be ready for the start of the season. Rodriguez missed one start. Only Brasier has required the team to reconfigure its roster for an extended period. In that regard, the Red Sox are atypical. They and Cleveland are the only teams not to have an injury since Opening Day that required a placement on the injured list. The other AL East contenders, meanwhile, have been hammered by injuries, contributing to their stumbles out of the gate. The Yankees have had seven players placed on the non-COVID injured list since the start of spring training, including surgeries on Zack Britton (shoulder) and Luke Voit (knee). -

120 Minor League Baseball Franchises

120 Minor League Baseball Franchises Federal Small Business Administration Paycheck Protection Program Club Class Value Owner Aberdeen Ironbirds High A Ripken Baseball / Ripken Holdings, LLC Akron RubberDucks AA Fast Forward Sports Group, LLC Albuquerque Isotopes AAA 14 Albuquerque Isotopes Baseball Club, LLC Altoona Curve AA Lozinak Baseball, LLC Amarillo Sod Poodles AA Panhandle Baseball Club, Inc. fg Elmore Sports Group Arkansas Travelers AA Arkansas Travelers Baseball Club, Inc. Asheville Tourists High A DeWine Seeds Silver Dollar Baseball, LLC Augusta GreenJackets Low A Augusta Professional Baseball, LLC fg Agon Sports and Entertainment, LLC Beloit Snappers High A Beloit Professional Baseball Association, Inc. fg Gateway Professional Baseball, LLC Biloxi Shuckers AA Biloxi Baseball, LLC Binghampton Rumble Ponies AA Evans Street Baseball, Inc. Birmingham Barons AA 13 Birmingham Barons, LLC Bowie Baysox AA Bowie Baysox Baseball Club, LLC fg Maryland Baseball Holding Company, LLC Bowling Green Hot Rods High A BG Sky, LLC Bradenton Marauders Low A Pittsburgh Pirates Brooklyn Cyclones High A Buffalo Bisons AAA 15 Rich Entertainment Group Carolina Mudcats Low A Milwaukee Brewers Cedar Rapids Kernels High A Cedar Rapids Ball Club, Inc. Charleston RiverDogs Low A South Carolina Baseball Club, LP fg Goldklang Group Charlotte Knights AAA 2 Knights Baseball, LLC fg Beaver Sports Properties, Inc. HardBall Capital, LLC ? Chattanooga Lookouts AA Chattanooga Professional Baseball, LLC = Clearwater Threshers Low A Philadelphia Phillies Columbia -

Scranton/Wilkes-Barre Railriders Game Notes Scranton/Wilkes-Barre Railriders (20-9) Vs

scranton/wilkes-barre railriders game notes Scranton/Wilkes-Barre RailRiders (20-9) vs. Buffalo Bisons (15-14) RHP Brian Keller (0-0, 3.18 ERA) vs. RHP Jacob Waguespack (1-1, 5.48 ERA) | Game 30 | Road Game 14 | Trenton Thunder Ballpark | Trenton, NJ | June 9, 2021 | First Pitch 7:00 p.m. | last time out... upcoming schedule / results TRENTON, N.J. (June 8, 2021) – The Scranton/Wilkes-Barre RailRiders erased an early 5-0 deficit to defeat the Buffalo Bisons 7-5 in a wild contest on date opponent result Tuesday night at Trenton Thunder Ballpark. June 4 Lehigh Valley L, 5-4 June 5 Lehigh Valley L, 9-6 After a one-hour, 45-minute weather delay to start the game, Zack Britton got the start in an MLB rehab assignment. The left-hander was tagged for four June 6 Lehigh Valley W, 4-3 runs in 0.1 innings of work. He allowed a two-run double to Tyler White and a two-run home run to Jared Hoying to stake Buffalo to an early 4-0 lead. June 8 @ Buffalo (Trenton) W, 7-5 Adam Warren allowed one run in 2.2 innings of relief in back of Britton, but the Bisons maintained a 5-0 advantage after the third. In the top of the June 9 @ Buffalo (Trenton) 7:00 p.m. fourth the RailRiders struck for three runs against Anthony Kay. Derek Dietrich drove home Hoy Park with an RBI single, and three batters later, Andrew June 10 @ Buffalo (Trenton) 7:00 p.m. -

* Text Features

The Boston Red Sox Wednesday, May 5, 2021 * The Boston Globe Hunter Renfroe is starting to find a groove, and that helped the Red Sox win series opener vs. Tigers Julian McWilliams Hunter Renfroe believed his swing was there. The approach despite the lackluster numbers (hitting just .191 entering Tuesday night) was there. Good fortune, Renfroe noted, wasn’t. ”I feel like I’ve been hitting the ball hard,” Renfroe said Sunday. “Just haven’t been finding a hole to hit it in. There’s no necessarily big adjustment for me to make right now except for just keeping the ball out of a glove.” On Tuesday, Renfroe finally saw his barrels meet results. In the Sox’ 11-7 win against the Tigers, Renfroe finished a triple shy of the cycle. His 3 for 4 night included two runs scored and two RBIs. In his at-bat in the seventh, Renfroe flied out on a hard-hit ball to right. If it weren’t caught, Renfroe would have had another extra-base hit, and he certainly had a triple on his mind. “I wasn’t going to stop at second, that’s for sure,” Renfroe said. “I was going to get thrown out at third before stopping at second. I was going for it.” In his past three games Renfroe has collected six hits, and seeing the ball drop has given him some sense of reprieve. “Any time you’re a baseball player, you want to see some hits fall,” Renfroe said. “It’s good. Like I said, just stay with my approach and I know it’s going to work out.