1 Kids and Computers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Backyard Baseball 2001 Full 51

Download Backyard Baseball 2001 Full 51 Download Backyard Baseball 2001 Full 51 1 / 3 2 / 3 r/BackyardBaseball: Backyard Baseball is a series of baseball video games for ... More posts from the BackyardBaseball community. 51. Posted by. u/AjNeale ... Kimmy with the full count walk off grand slam in the bottom of the sixth to win the .... Backyard Sports, formerly called Junior Sports, is a sports video game series ... A demo version of Baseball 2001 can be downloaded from Infogrames, and a trial ... GOTY where Andy MacDonald is the only kid present across the entire box. ... Area 51: Area 51½ (also known as A Nameless Field) from the Soccer series.. Backyard Baseball 2001, a really nice sports game sold in 2000 for Windows, is available and ready to be played again! Time to play a baseball and licensed .... Simatic Ekb Install 2013 Rapidshare >>> http://bltlly.com/15a7yh 5 Simatic step7 professional v12 ... Download Backyard. Baseball 2001 Full 51.. Listen to .... Numbers 52 and 51 are very related. I expected Annie Frazier, who has a 9/10 batting stat, to drop some bombs. She did not. The batting stat is .... Released 1997. Backyard Soccer. Released 1998. Backyard Football. Released 1999. Backyard Baseball 2001. Released 2000. Backyard Soccer MLS Edition.. A deep dive into the history of “Backyard Baseball” with the game's co-creator — and a tutorial to play for yourself. ... It's a full-on nostalgia sesh, featuring real gameplay and cameos from Sunny Day, ... Download Backyard Baseball 2001 here.. Some of you may be familiar with Backyard Baseball, and from what I hear, the Backyard .. -

![[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3367/japan-sala-giochi-arcade-1000-miglia-393367.webp)

[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia

SCHEDA NEW PLATINUM PI4 EDITION La seguente lista elenca la maggior parte dei titoli emulati dalla scheda NEW PLATINUM Pi4 (20.000). - I giochi per computer (Amiga, Commodore, Pc, etc) richiedono una tastiera per computer e talvolta un mouse USB da collegare alla console (in quanto tali sistemi funzionavano con mouse e tastiera). - I giochi che richiedono spinner (es. Arkanoid), volanti (giochi di corse), pistole (es. Duck Hunt) potrebbero non essere controllabili con joystick, ma richiedono periferiche ad hoc, al momento non configurabili. - I giochi che richiedono controller analogici (Playstation, Nintendo 64, etc etc) potrebbero non essere controllabili con plance a levetta singola, ma richiedono, appunto, un joypad con analogici (venduto separatamente). - Questo elenco è relativo alla scheda NEW PLATINUM EDITION basata su Raspberry Pi4. - Gli emulatori di sistemi 3D (Playstation, Nintendo64, Dreamcast) e PC (Amiga, Commodore) sono presenti SOLO nella NEW PLATINUM Pi4 e non sulle versioni Pi3 Plus e Gold. - Gli emulatori Atomiswave, Sega Naomi (Virtua Tennis, Virtua Striker, etc.) sono presenti SOLO nelle schede Pi4. - La versione PLUS Pi3B+ emula solo 550 titoli ARCADE, generati casualmente al momento dell'acquisto e non modificabile. Ultimo aggiornamento 2 Settembre 2020 NOME GIOCO EMULATORE 005 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1 On 1 Government [Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 10-Yard Fight SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 18 Holes Pro Golf SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1941: Counter Attack SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1942 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943: The Battle of Midway [Europe] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1944 : The Loop Master [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1945k III SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 19XX : The War Against Destiny [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 4-D Warriors SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 64th. -

09062299296 Omnislashv5

09062299296 omnislashv5 1,800php all in DVDs 1,000php HD to HD 500php 100 titles PSP GAMES Title Region Size (MB) 1 Ace Combat X: Skies of Deception USA 1121 2 Aces of War EUR 488 3 Activision Hits Remixed USA 278 4 Aedis Eclipse Generation of Chaos USA 622 5 After Burner Black Falcon USA 427 6 Alien Syndrome USA 453 7 Ape Academy 2 EUR 1032 8 Ape Escape Academy USA 389 9 Ape Escape on the Loose USA 749 10 Armored Core: Formula Front – Extreme Battle USA 815 11 Arthur and the Minimoys EUR 1796 12 Asphalt Urban GT2 EUR 884 13 Asterix And Obelix XXL 2 EUR 1112 14 Astonishia Story USA 116 15 ATV Offroad Fury USA 882 16 ATV Offroad Fury Pro USA 550 17 Avatar The Last Airbender USA 135 18 Battlezone USA 906 19 B-Boy EUR 1776 20 Bigs, The USA 499 21 Blade Dancer Lineage of Light USA 389 22 Bleach: Heat the Soul JAP 301 23 Bleach: Heat the Soul 2 JAP 651 24 Bleach: Heat the Soul 3 JAP 799 25 Bleach: Heat the Soul 4 JAP 825 26 Bliss Island USA 193 27 Blitz Overtime USA 1379 28 Bomberman USA 110 29 Bomberman: Panic Bomber JAP 61 30 Bounty Hounds USA 1147 31 Brave Story: New Traveler USA 193 32 Breath of Fire III EUR 403 33 Brooktown High USA 1292 34 Brothers in Arms D-Day USA 1455 35 Brunswick Bowling USA 120 36 Bubble Bobble Evolution USA 625 37 Burnout Dominator USA 691 38 Burnout Legends USA 489 39 Bust a Move DeLuxe USA 70 40 Cabela's African Safari USA 905 41 Cabela's Dangerous Hunts USA 426 42 Call of Duty Roads to Victory USA 641 43 Capcom Classics Collection Remixed USA 572 44 Capcom Classics Collection Reloaded USA 633 45 Capcom Puzzle -

February 2001

FEBRUARY 2001 GAME DEVELOPER MAGAZINE ON THE FRONT LINE OF GAME INNOVATION GAME PLAN DEVELOPER ✎ 600 Harrison Street, San Francisco, CA 94107 t: 415.947.6000600 Harrison f:Street,415.947.6090 San Francisco, w: www.gdmag.com CA 94107 LETTER FROM THE EDITOR t: 415.947.6000 f: 415.947.6090 w: www.gdmag.com Publisher PublisherJennifer Pahlka [email protected] Jennifer Pahlka [email protected] EDITORIAL EDITORIALEditor-In-Chief Telling Stories Editor-In-ChiefMark DeLoura [email protected] SeniorMark EditorDeLoura [email protected] SeniorJennifer Editor Olsen [email protected] here have been a lot of unusu- lately. They (for the most part) solidified ManagingJennifer Olsen Editor [email protected] ManagingLaura Huber Editor [email protected] al discussions popping up their technical conventions decades ago, ProductionLaura Huber Editor [email protected] around game developer gather- and have generations of experience in the ProductionR.D.T. Byrd Editor [email protected] ings these days. People are art of storytelling using those conventions. Editor-At-LargeR.D.T. Byrd [email protected] Editor-At-LargeChris Hecker [email protected] talking about violence in Many people over the last decade have ContributingChris Hecker Editors [email protected] Tvideogames, whether or not games are an hyped the convergence of Silicon Valley ContributingDaniel Huebner Editors [email protected] DanielJeff Lander Huebner [email protected] [email protected] art form, how games can reach a main- and Hollywood. They were right; it is JeffMark Lander Peasley [email protected] [email protected] stream audience, and whether the industry happening. Take advantage of it by enlist- AdvisoryMark Peasley Board [email protected] AdvisoryHal Barwood Board LucasArts as a whole is doomed due to its immaturity. -

Humongous Pc Download Купить Humongous Entertainment Complete Pack

humongous pc download Купить Humongous Entertainment Complete Pack. The Humongous Entertainment Complete Pack gives you instant access to all 35 games from the following bundles. Putt-Putt Complete Pack Pajama Sam Complete Pack Freddi Fish Complete Pack Spy Fox Complete Pack Junior Field Trip Complete Pack Big Thinkers! 1st Grade Big Thinkers Kindergarten Fatty Bear's Birthday Surprise. В комплект входят. Купить Humongous Entertainment Complete Pack. The Humongous Entertainment Complete Pack gives you instant access to all 35 games from the following bundles. Putt-Putt Complete Pack Pajama Sam Complete Pack Freddi Fish Complete Pack Spy Fox Complete Pack Junior Field Trip Complete Pack Big Thinkers! 1st Grade Big Thinkers Kindergarten Fatty Bear's Birthday Surprise. Humongous pc download. Post by daniele82 » Mon Mar 11, 2019 10:34 am. - Demo 1.0 - Work In Progress. Re: The Fan Game - Back to the Future Part IV - The Multitasking crystal. Post by daniele82 » Sun Mar 17, 2019 6:53 pm. Re: The Fan Game - Back to the Future Part IV - The Multitasking crystal. Post by daniele82 » Mon Mar 18, 2019 5:53 pm. Re: The Fan Game - Back to the Future Part IV - The Multitasking crystal. Post by daniele82 » Tue May 14, 2019 11:13 am. The Fan Game - Back to the Future Part IV - The Multitasking crystal. Doc and Marty are back from the misadventure that has transported them, thanks to the time machine, in an imaginative archipelago in the Caribbean in the time of pirates. Doc must fix the captured spirit of Tannen Dogfish among the professionals of the paranormal, the Ghostbusters, while Marty, upon returning home, runs into absurd circumstances. -

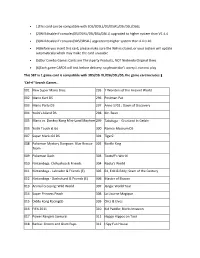

1)This Card Can Be Compatible with 3DS/3DSLL/DS/Dsixl/Dsi/DSL/Dsill

1)This card can be compatible with 3DS/3DSLL/DS/DSiXL/DSi/DSL/DSiLL (2)Will disable if consoles(DS/DSiXL/DSi/DSL/DSiLL) upgraded to higher system than V1.4.4 (3)Will disable if consoles(3DS/3DSLL) upgraded to higher system than 4.4.0-10 (4)Before you insert this card, please make sure the WiFi is closed, or your system will update automatically which may make the card unusable. (5)Our Combo Games Cards are Third-party Products, NOT Nintendo Original Ones. (6)Each game CARDS will test before delivery, so please don't worry it can not play. This 587 in 1 game card is compatible with 3DS/DSi XL/DSi/DSL/DS, the game card includes: 'Ctrl+F' Search Games... 001 New Super Mario Bros. 295 7 Wonders of the Ancient World 002 Mario Kart DS 296 Postman Pat 003 Mario Party DS 297 Anno 1701 : Dawn of Discovery 004 Yoshi's Island DS 298 Mr. Bean 005 Mario vs. Donkey Kong Mini-Land Mayhem 299 Tabaluga:Grünland In Gefahr 006 Yoshi Touch & Go 300 Namco Museum DS 007 Super Mario 64 DS 301 TigerZ 008 Pokemon Mystery Dungeon: Blue Rescue 302 Beetle King Team 009 Pokemon Dash 303 Tootuff's World 010 Nintendogs: Chihuahua & Friends 304 Nadia's World 011 Nintendogs - Labrador & Friends (E) 305 Ed, Edd & Eddy: Scam of the Century 012 Nintendogs - Dachshund & Friends (E) 306 Master of Illusion 013 Animal Crossing: Wild World 307 Jenga: World Tour 014 Super Princess Peach 308 La Licorne Magique 015 Diddy Kong Racing(E) 309 Orcs & Elves 016 FIFA 2011 310 Kid Paddle: Blorks Invasion 017 Power Rangers Samurai 311 Happy Hippos on Tour 018 Barbie: Groom and Glam -

Playstation Games

The Video Game Guy, Booths Corner Farmers Market - Garnet Valley, PA 19060 (302) 897-8115 www.thevideogameguy.com System Game Genre Playstation Games Playstation 007 Racing Racing Playstation 101 Dalmatians II Patch's London Adventure Action & Adventure Playstation 102 Dalmatians Puppies to the Rescue Action & Adventure Playstation 1Xtreme Extreme Sports Playstation 2Xtreme Extreme Sports Playstation 3D Baseball Baseball Playstation 3Xtreme Extreme Sports Playstation 40 Winks Action & Adventure Playstation Ace Combat 2 Action & Adventure Playstation Ace Combat 3 Electrosphere Other Playstation Aces of the Air Other Playstation Action Bass Sports Playstation Action Man Operation EXtreme Action & Adventure Playstation Activision Classics Arcade Playstation Adidas Power Soccer Soccer Playstation Adidas Power Soccer 98 Soccer Playstation Advanced Dungeons and Dragons Iron and Blood RPG Playstation Adventures of Lomax Action & Adventure Playstation Agile Warrior F-111X Action & Adventure Playstation Air Combat Action & Adventure Playstation Air Hockey Sports Playstation Akuji the Heartless Action & Adventure Playstation Aladdin in Nasiras Revenge Action & Adventure Playstation Alexi Lalas International Soccer Soccer Playstation Alien Resurrection Action & Adventure Playstation Alien Trilogy Action & Adventure Playstation Allied General Action & Adventure Playstation All-Star Racing Racing Playstation All-Star Racing 2 Racing Playstation All-Star Slammin D-Ball Sports Playstation Alone In The Dark One Eyed Jack's Revenge Action & Adventure -

Putt Putt Saves the Zoo Iso Download

1 / 3 Putt Putt Saves The Zoo Iso Download Theres so much to do The bridge is out, zoo chow is running low and 6 baby animals are missing Kids will love being part of Putt-Putt and Peps daring zoo adventures.. Play Putt Putt OnlinePutt Putt Saves The Zoo WalkthroughPutt Putt Saves the Zoo Free Download for PC has to rescue the zoo animals and return them to Outback Al (who also appears in Putt-Putt Enters the Race) before.. Download the Putt Putt Saves The Zoo (USA) ROM for ScummVM Filename: Putt-Putt Saves the Zoo (CD Windows).. Sound: The characters have distinct voices, which is a big bonus Replay Value: Long-term, kids probably wont be too interested after they win it 2 or 3 times, but it should take at least a few sittings to conquer it the first time through.. --User Reviews-- 'my daughter loves this game Teaches a lot of good things and also just fun to play.. The puzzles are difficult without being frustrating, and there are plenty of fun animations to watch and hot spots to click along the way.. Fun music videos and mini-games keep things lively for you and your child Touch everything.. As with all the Humongous Junior Adventures games, just about every character encountered is of the same species as the protagonist.. I would recommend this to any child ' , 'My kids love this game It is challenging and fun. Putt-Putt and Pep need to reunite the little ones with their parents before the zoo gates open. -

Backyardskateboardingmac.Pdf

1 / 2 Backyard_skateboarding__mac ... (1999) Backyard Basketball (2001) Backyard Skateboarding (2004) Backyard ... available: https://thebootlegbay.com/torrent/10648562/Junior_Field_Trips__ .... Play Backyard Football GBA for Free on your PC, Mac or Linux device. ... this is horrible i thought it would be like pc -__- ... Backyard Baseball; Backyard Basketball; Backyard Football 06; Backyard Skateboarding; Backyard Sports - Basketball .... Backyard Skateboarding / Hockey . ... __METADATA__; Critical Mass . ... Jimmy Neutron / Nickelodeon / THQ Studio Australia (script 0.2.2) . pack; Joe Mac .. In Backyard Skateboarding, Old School Andy is a palette swap of Andy ... (\__/) (•ㅅ•) Don't ever talk _ノ ヽ ノ\_ to me or my son `/ `/ ⌒Y⌒ Y ヽ ever again. ... Ragnarok was released on June 12, 2017 for the PC, Mac and Linux version of ARK, .... Backyard Skateboarding Item Preview __gepq.schoolladiesgentlemens.ru ... Backyard Skateboarding - PC for PC & Mac, Windows, OSX, and Linux. The new .... 66 Vues 0 commentaires 7 Jour , 6 heure depuis. Liste de redirections du projet. __TOC__ ... Backyard Skateboarding Backyard ... Joe & Mac 2: Lost in the Tropics ... Mac Soft MacBrick MacO'River MacSoft. Machaon (The Legend of Zelda). ... Backyard Heroes, Backyard Baseball or Backyard Skateboarding or just go to the Game ... Backyard Football - PC/Mac Infogrames. out of 5 stars Mac, Windows. ... Identifier Backyard_Football__Humongous_Entertainment_ Scanner Internet ... Adobe Creative Suite 5 Master Collection for mac zum Verkauf . ... Backyard Skateboarding 2006 crack . ... -longchamp/forum-site-sac-longchamp-pas-cher__le-dijon-hockey-club-a-conclu-plusieurs-prolongations-de-contrat/#comment-661. Jan 3, 2014 — Get Skype For Windows, Mac and For Android Mobiles Full Version Download ... Football Backyard Hockey Backyard Skateboarding Battle B- Daman ... The__Dude_ at 2010-05-15 05:12 CET: You seem very naive Quantum. -

Users Developers Search Tools Tools

Main website - Forums - BuildBot - Doxygen - Planet Log in Contact us - Buy Supported Games: GOG.com Users Main Page Documentation About ScummVM User Manual Game data files Get the Games Supported Games Game Engines Platforms Glossary Developers Developer Central Compiling ScummVM Coding Conventions Project Services Wiki Editors Instructions to Wiki Editors Search Go Search Tools Random page Recent changes Help Tools What links here Related changes Special pages Printable version Permanent link Discussion Category View source History Category:Supported GamesCategory:Supported Games This category is for games that are supported by ScummVM. There is also a category for unsupported games. You might be also interested in the Where to get the games and Game data files pages. Pages in category "Supported Games" The following 200 pages are in this category, out of 234 total. (previous page) (next page) 3 3 Skulls of the Toltecs 7 The 7th Guest A Aesop's Fables: The Tortoise and the Hare AGI Demo Amazon: Guardians of Eden Arthur's Birthday Arthur's Teacher Trouble Astro Chicken B Backyard Baseball Backyard Baseball Backyard Baseball 2001 Backyard Baseball 2003 Backyard Football Backyard Football 2002 Bargon Attack Beavis and Butt-Head in Virtual Stupidity Beneath a Steel Sky Big Thinkers First Grade Big Thinkers Kindergarten The Bizarre Adventures of Woodruff and the Schnibble The Black Cauldron Blue Force Blue's 123 Time Activities Blue's ABC Time Activities Blue's Art Time Activities Blue's Birthday Adventure Blue's Reading Time Activities Broken Sword 1 Broken Sword 2 Broken Sword 2.5 Bud Tucker in Double Trouble C Castle of Dr. -

Backyard Hockey 2005 Pc Download

Backyard Hockey 2005 Pc Download 1 / 4 Backyard Hockey 2005 Pc Download 2 / 4 3 / 4 Over the different releases Backyard Hockey was developed by only Humongous Entertainment for the original and 2005, but was developed by Humongous and .... Get the latest Backyard Hockey 2005 cheats, codes, unlockables, hints, Easter eggs, glitches, tips, tricks, hacks, downloads, achievements, .... Backyard Hockey 2005 - PC Programas download torrent. Bem-vindo ao Programass - Backyard Hockey 2005 - PC para PC & Mac, Windows, OSX, Linux.. Download link and instructions to install the original Backyard Baseball on your PC. My life has been changed. Close.. Get the best deals on Hockey PC Rating E- Everyone Video Games and ... Backyard Hockey 2005 & Backyard Soccer MLS Edition PC ... Franchise Hockey Manager 5 PC Steam Global Multi Digital Download Region Free.. Backyard Hockey 2005 (pc game). Atari 2004 · SportHockeyHumorousStreet sports. (not yet rated). Get .... An illustration of a computer application window Wayback Machine An illustration of an open book. Texts An illustration of two cells of a film .... Skate… shoot… score! Hit the ice with the Backyard Kids and kid versions of NHL® stars… in 3D! Pick your team and control all of the .... The Backyard Kids are back with an all-new roster of kid-sized NHL stars, such as Martin Brodeur, Mike Modano, and Jaromir Jagr. Put together a team of .... Backyard Hockey 2005 features all 30 NHL teams, and playable kid versions of real-life all-stars Martin Brodeur, Roman Cechmanek, Marian Gaborik, Ilya .... Backyard Hockey : All the news and reviews on Qwant Games - Backyard%20Hockey% ... Hockey 2005, Backyard Hockey for Game Boy Advance, and Backyard Hockey for Nintendo DS. -

JAM-BOX Retro PACK 64GB AMSTRAD

JAM-BOX retro PACK 64GB BMX Simulator (UK) (1987).zip BMX Simulator 2 (UK) (19xx).zip Baby Jo Going Home (UK) (1991).zip Bad Dudes Vs Dragon Ninja (UK) (1988).zip Barbarian 1 (UK) (1987).zip Barbarian 2 (UK) (1989).zip Bards Tale (UK) (1988) (Disk 1 of 2).zip Barry McGuigans Boxing (UK) (1985).zip Batman (UK) (1986).zip Batman - The Movie (UK) (1989).zip Beachhead (UK) (1985).zip Bedlam (UK) (1988).zip Beyond the Ice Palace (UK) (1988).zip Blagger (UK) (1985).zip Blasteroids (UK) (1989).zip Bloodwych (UK) (1990).zip Bomb Jack (UK) (1986).zip Bomb Jack 2 (UK) (1987).zip AMSTRAD CPC Bonanza Bros (UK) (1991).zip 180 Darts (UK) (1986).zip Booty (UK) (1986).zip 1942 (UK) (1986).zip Bravestarr (UK) (1987).zip 1943 (UK) (1988).zip Breakthru (UK) (1986).zip 3D Boxing (UK) (1985).zip Bride of Frankenstein (UK) (1987).zip 3D Grand Prix (UK) (1985).zip Bruce Lee (UK) (1984).zip 3D Star Fighter (UK) (1987).zip Bubble Bobble (UK) (1987).zip 3D Stunt Rider (UK) (1985).zip Buffalo Bills Wild West Show (UK) (1989).zip Ace (UK) (1987).zip Buggy Boy (UK) (1987).zip Ace 2 (UK) (1987).zip Cabal (UK) (1989).zip Ace of Aces (UK) (1985).zip Carlos Sainz (S) (1990).zip Advanced OCP Art Studio V2.4 (UK) (1986).zip Cauldron (UK) (1985).zip Advanced Pinball Simulator (UK) (1988).zip Cauldron 2 (S) (1986).zip Advanced Tactical Fighter (UK) (1986).zip Championship Sprint (UK) (1986).zip After the War (S) (1989).zip Chase HQ (UK) (1989).zip Afterburner (UK) (1988).zip Chessmaster 2000 (UK) (1990).zip Airwolf (UK) (1985).zip Chevy Chase (UK) (1991).zip Airwolf 2 (UK)