IAFOR Journal of Education Volume 4 Issue 2.Docx

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ISDM IAPO 2017 Prog Book I

17th International Symposium on Dental Morphology & 2nd congress of International Association for Paleodontology 4‐7 October 2017 BORDEAUX│France CONTENT WELCOME LETTER .......................................................................................................................... 3 ORGANIZING BOARD ..................................................................................................................... 4 SCIENTIFIC BOARD ......................................................................................................................... 5 SUPPORTING INSTITUTIONS & SPONSORS ..................................................................................... 6 PROGRAM ..................................................................................................................................... 7 ABSTRACTS ................................................................................................................................... 22 1. DENTAL EVOLUTION IN DEEP TIME ........................................................................................................ 23 2. TEETH AND ARCHAEOLOGY (HUMANS & ANIMALS) .................................................................................. 38 3. DENTAL GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT ................................................................................................... 78 4. DENTAL FUNCTION AND BIOMECHANICS .............................................................................................. 101 5. ODONTOLOGY AND PALEODONTOLOGY............................................................................................... -

This Checklist Is Generated Using RF Generation's Database This Checklist Is Updated Daily, and It's Completeness Is Dependent on the Completeness of the Database

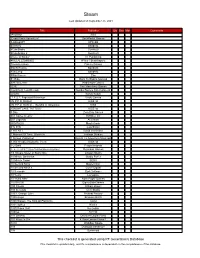

Steam Last Updated on September 25, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments !AnyWay! SGS !Dead Pixels Adventure! DackPostal Games !LABrpgUP! UPandQ #Archery Bandello #CuteSnake Sunrise9 #CuteSnake 2 Sunrise9 #Have A Sticker VT Publishing #KILLALLZOMBIES 8Floor / Beatshapers #monstercakes Paleno Games #SelfieTennis Bandello #SkiJump Bandello #WarGames Eko $1 Ride Back To Basics Gaming √Letter Kadokawa Games .EXE Two Man Army Games .hack//G.U. Last Recode Bandai Namco Entertainment .projekt Kyrylo Kuzyk .T.E.S.T: Expected Behaviour Veslo Games //N.P.P.D. RUSH// KISS ltd //N.P.P.D. RUSH// - The Milk of Ultraviolet KISS //SNOWFLAKE TATTOO// KISS ltd 0 Day Zero Day Games 001 Game Creator SoftWeir Inc 007 Legends Activision 0RBITALIS Mastertronic 0°N 0°W Colorfiction 1 HIT KILL David Vecchione 1 Moment Of Time: Silentville Jetdogs Studios 1 Screen Platformer Return To Adventure Mountain 1,000 Heads Among the Trees KISS ltd 1-2-Swift Pitaya Network 1... 2... 3... KICK IT! (Drop That Beat Like an Ugly Baby) Dejobaan Games 1/4 Square Meter of Starry Sky Lingtan Studio 10 Minute Barbarian Studio Puffer 10 Minute Tower SEGA 10 Second Ninja Mastertronic 10 Second Ninja X Curve Digital 10 Seconds Zynk Software 10 Years Lionsgate 10 Years After Rock Paper Games 10,000,000 EightyEightGames 100 Chests William Brown 100 Seconds Cien Studio 100% Orange Juice Fruitbat Factory 1000 Amps Brandon Brizzi 1000 Stages: The King Of Platforms ltaoist 1001 Spikes Nicalis 100ft Robot Golf No Goblin 100nya .M.Y.W. 101 Secrets Devolver Digital Films 101 Ways to Die 4 Door Lemon Vision 1 1010 WalkBoy Studio 103 Dystopia Interactive 10k Dynamoid This checklist is generated using RF Generation's Database This checklist is updated daily, and it's completeness is dependent on the completeness of the database. -

Official Conference Proceedings ISSN: 2189 - 101X

Official Conference Proceedings ISSN: 2189 - 101X “To Open Minds, To Educate Intelligence, To Inform Decisions” The International Academic Forum provides new perspectives to the thought-leaders and decision-makers of today and tomorrow by offering constructive environments for dialogue and interchange at the intersections of nation, culture, and discipline. Headquartered in Nagoya, Japan, and registered as a Non-Profit Organization 一般社( 団法人) , IAFOR is an independent think tank committed to the deeper understanding of contemporary geo-political transformation, particularly in the Asia Pacific Region. INTERNATIONAL INTERCULTURAL INTERDISCIPLINARY iafor The Executive Council of the International Advisory Board IAB Chair: Professor Stuart D.B. Picken IAB Vice-Chair: Professor Jerry Platt Mr Mitsumasa Aoyama Professor June Henton Professor Baden Offord Director, The Yufuku Gallery, Tokyo, Japan Dean, College of Human Sciences, Auburn University, Professor of Cultural Studies and Human Rights & Co- USA Director of the Centre for Peace and Social Justice Professor David N Aspin Southern Cross University, Australia Professor Emeritus and Former Dean of the Faculty of Professor Michael Hudson Education, Monash University, Australia President of The Institute for the Study of Long-Term Professor Frank S. Ravitch Visiting Fellow, St Edmund’s College, Cambridge Economic Trends (ISLET) Professor of Law & Walter H. Stowers Chair in Law University, UK Distinguished Research Professor of Economics, The and Religion, Michigan State University College of Law University of Missouri, Kansas City Professor Don Brash Professor Richard Roth Former Governor of the Reserve Bank, New Zealand Professor Koichi Iwabuchi Senior Associate Dean, Medill School of Journalism, Former Leader of the New National Party, New Professor of Media and Cultural Studies & Director of Northwestern University, Qatar Zealand the Monash Asia Institute, Monash University, Australia Adjunct Professor, AUT, New Zealand & La Trobe Professor Monty P. -

Gunz 2 Korean Download

Gunz 2 korean download GunZ 2: the Second Duel is a free-to-play 3D TPS and is the most fast-paced tough action shooter Interface, Full Audio, Subtitles. English. Korean. Japanese. Well, I have been playing a lot more in the Korean servers trying to compare the play styles from the US and. Featured video: Gunz 2 Korean Beta Impressions w/ Mikedot i have problem with patch when lunching the game i can't download ithe patch please help:. GunZ. Download GunZ: The Duel Beta. 2/1/ Downloads: Also. This is the beta patch for GunZ: The Duel. First released in Korea Gunz 2 content is not. GunZ 2 provides a whole new user experience that players. it to February because of the Lunar New Year's day holiday (1/30~2/1) in Korea. I hear it's because the gaming market in South Korea is complete bullcrap now, biased towards mobile gaming, so the only desktop games. DOWNLOAD THE ORIGINAL SIZE OF GUNZ 2 Images, and SET AS YOUR DESKTOP I gained this knowledge from a Korean friend of mine. Maiet will be. GunZ 2: The Second Duel, free and safe download. GunZ 2: The Second Duel latest version: GunZ 2: the Second Duel is a free-to-play 3D TPS and is the most. Gunz 2: The Second Duel also known as Gunz is a war video game. It was originally released in Korea in It requires at least Windows XP to work effici. [Download] Just a friendly reminder to everyone, GunZ 2: The Second Duel is now Korean developer Maiet Entertainment finally announced that GunZ 2: The.