National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This Form Is for Use in Nominating Or Requesting Determinations for Individual Properties and Districts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

US EPA Launches Redevelopment of P&LE

U.S. EPA Launches Redevelopment of P&LE Railroad Brownfield Site; New Funding for Environmental Assessments at Additional Sites Former P&LE Railroad brownfield site to be new business park yielding 1,172 new jobs, 642 construction-related jobs, and total state and local taxes in excess of $13 million New $1 million federal funding announced for environmental assessments of additional brownfield sites in Pittsburgh region (PITTSBURGH – June 20, 2011) –U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Mid-Atlantic Regional Administrator Shawn Garvin will join elected officials and community leaders today to announce two important milestones in the continuing redevelopment of former industrial (“brownfield”) sites in the Pittsburgh region. Garvin will announce the launch of the redevelopment of the P&LE Railroad brownfield site in McKees Rocks, Pa. The EPA has provided funding for the environmental assessment of this site – the first step in redeveloping the site for future business investment. Trinity Commercial Development, LLC , the redevelopment contractor for the site, has acquired the parcels necessary to begin redevelopment. Garvin will also award new federal funding of $1 million for environmental assessment to the North Side Industrial Development Company, a non-profit development organization, for use on additional brownfield sites located within the River Towns Coalition communities (note to editor: list of River Town Coalition members appears at the end of the release). “EPA is proud to participate in projects where local partners work together to transform a site, such as the P&LE property, into a vibrant facility that benefits the entire community," said EPA mid-Atlantic Regional Administrator Shawn M. -

Urban Redevelopment Authority of Pittsburgh 2015 Tax Increment Financing Report

FINANCING OUR FUTURE Urban Redevelopment Authority of Pittsburgh 2015 Tax Increment Financing Report 2015 FINANCING OUR FUTURE In 2015, the Urban Redevelopment Authority of Pittsburgh (URA) continued leading transformative growth in neighborhoods throughout the City of Pittsburgh. Creative public financing led to the implementation of an affordable housing fund in East Liberty, restoration of riverfront access in the Strip District, an equitable redevelopment fund for the Hill District, and the groundbreaking of the 178-acre Almono site in Hazelwood. Each of these tax increment financing (TIF) projects is utilizing economic growth in our City to finance transformative public infrastructure improvements. The URA also announced that $13.6 million in additional real estate and parking tax revenue will be collected by the City of Pittsburgh, Allegheny County and Pittsburgh Public Schools over the next three years due to the full prepayment of South Side Works TIF District debt. Through seamless integration with the surrounding community, the landmark riverfront brownfield redevelopment has added nearly 4,900 jobs, 1,000 residential units, 2.3 million square feet of commercial activity, and a signature public park, marina and trail development that provides critical connectivity to the Great Allegheny Passage system. Tax increment financing continues to be a vital mechanism through which and improves quality of life for our residents. Amidst diminishing federal and state economic development funding, our 29 TIF projects have financed $336 million in critical public infrastructure investments that have leveraged nearly $3 billion in private capital. Together with our partners at the City, County and School District, the URA is expanding the resources with which we have to make Pittsburgh an even more livable and competitive urban center. -

Helen Frick and the True Blue Girls

Helen Frick and the True Blue Girls Jack E. Hauck Treasures of Wenham History, Helen Frick Pg. 441 Helen Frick and the True Blue Girls In Wenham, for forty-five years Helen Clay Frick devoted her time, her resources and her ideas for public good, focusing on improving the quality of life of young, working-class girls. Her style of philanthropy went beyond donating money: she participated in helping thousands of these girls. It all began in the spring of 1909, when twenty-year-old Helen Frick wrote letters to the South End Settlement House in Boston, and to the YMCAs and churches in Lowell, Lawrence and Lynn, requesting “ten promising needy Protestant girls to be selected for a free two-week stay ”in the countryside. s In June, she welcomed the first twenty-four young women, from Lawrence, to the Stillman Farm, in Beverly.2, 11 All told, sixty-two young women vacationed at Stillman Farm, that first summer, enjoying the fresh air, open spaces and companionship.2 Although Helen monitored every detail of the management and organization, she hired a Mrs. Stefert, a family friend from Pittsburgh, to cook meals and run the home.2 Afternoons were spent swimming on the ocean beach at her family’s summer house, Eagle Rock, taking tea in the gardens, or going to Hamilton to watch a horse show or polo game, at the Myopia Hunt Club.2 One can only imagine how awestruck these young women were upon visiting the Eagle Rock summer home. It was a huge stone mansion, with over a hundred rooms, expansive gardens and a broad view of the Atlantic Ocean. -

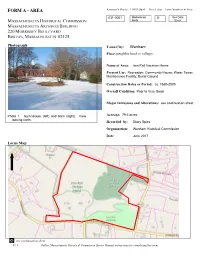

FORM a - AREA Assessor’S Sheets USGS Quad Area Letter Form Numbers in Area

FORM A - AREA Assessor’s Sheets USGS Quad Area Letter Form Numbers in Area 031-0001 Marblehead G See Data MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL COMMISSION North Sheet ASSACHUSETTS RCHIVES UILDING M A B 220 MORRISSEY BOULEVARD BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS 02125 Photograph Town/City: Wenham Place (neighborhood or village): Name of Area: Iron Rail Vacation Home Present Use: Recreation; Community House; Water Tower; Maintenance Facility; Burial Ground Construction Dates or Period: ca. 1880-2009 Overall Condition: Poor to Very Good Major Intrusions and Alterations: see continuation sheet Photo 1. Gymnasium (left) and barn (right). View Acreage: 79.6 acres looking north. Recorded by: Stacy Spies Organization: Wenham Historical Commission Date: June 2017 Locus Map see continuation sheet 4 /1 1 Follow Massachusetts Historical Commission Survey Manual instructions for completing this form. INVENTORY FORM A CONTINUATION SHEET WENHAM IRON RAIL VACATION HOME MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL COMMISSION Area Letter Form Nos. 220 MORRISSEY BOULEVARD, BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS 02125 G See Data Sheet Recommended for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. If checked, you must attach a completed National Register Criteria Statement form. Use as much space as necessary to complete the following entries, allowing text to flow onto additional continuation sheets. ARCHITECTURAL DESCRIPTION Describe architectural, structural and landscape features and evaluate in terms of other areas within the community. The Iron Rail Vacation Home property at 91 Grapevine Road is comprised of buildings and landscape features dating from the multiple owners and uses of the property over the 150 years. The extensive property contains shallow rises surrounded by wetlands. Woodlands are located at the north half of the property and wetlands are located at the northwest and central portions of the property. -

Paul Hedren's Burial Places of Officers, Physicians, and Other

All Rights Reserved, 2011, Paul L. Hedren [updated 9-19-11] WHERE ARE THEY NOW? Burial places of officers, physicians, and other military notables of the Great Sioux War compiled by Paul L. Hedren Introduction The names in this “Where Are They Now?” compilation are drawn from Great Sioux War Orders of Battle: How the United States Army Waged War on the Northern Plains, 1876-1877 (Norman, Okla.: Arthur H. Clark Company, 2011), which acknowledges in context every officer and physician engaged in this Indian war. The intent here is to identify the dates of death and burial places of these individuals. The ranks and affiliations given are timely to the war, not to later service. The dates of death and burial places provided are largely drawn from the sources noted at the end. Details that are probable but unconfirmed are noted within parentheses. This compilation is a work-in- progress and I welcome additional information and/or corrections and will strive to keep the file current. Please write me in care of <[email protected]>. AAA Adam, Emil, Captain, Fifth Cavalry, d January 16, 1903. Allison, James Nicholas, Second Lieutenant, Second Cavalry, d May 2, 1918. Anderson, Harry Reuben, First Lieutenant, Fourth Artillery, d November 22, 1918, Arlington National Cemetery, Arlington, Virginia. Andrews, William Howard, Captain, Third Cavalry, d June 21, 1880. Andrus, Edwin Procter, Second Lieutenant, Fifth Cavalry, d September 27, 1930, Arlington National Cemetery, Arlington, Virginia. Arthur, William, Major, Pay Department, d February 27, 1915. Ashton, Isaiah Heylin, Acting Assistant Surgeon, d February 16, 1889, Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, Sleepy Hollow, New York. -

PRESS RELEASE from the FRICK COLLECTION

ARCHIVED PRESS RELEASE from THE FRICK COLLECTION 1 EAST 70TH STREET • NEW YORK • NEW YORK 10021 • TELEPHONE (212) 288-0700 • FAX (212) 628-4417 WITH RETIREMENT OF ANDREW W. MELLON CHIEF LIBRARIAN PATRICIA BARNETT, FRICK ART REFERENCE LIBRARY MARKS 13 YEARS OF ACHIEVEMENT The Frick Art Reference Library announces the retirement of Patricia Barnett, Andrew W. Mellon Chief Librarian. Comments Director Anne L. Poulet, “During her thirteen years as Chief Librarian, Pat Barnett has been a champion of outreach and collaboration. As a result, the Frick Art Reference Library has strengthened its position as an innovative institution, one that colleagues both in the United States and Europe view as an exemplar of best practices in librarianship and new initiatives. I speak for The Frick Collection staff and Board of Trustees in commending Pat Barnett for her dynamic and transformative years of service, and we congratulate her for the long list of accomplishments during her stewardship at the Library.” Adds Margot Bogert, Chairman of The Frick Collection’s Board of Trustees, “Pat Barnett leaves the Frick Art Reference Library a vital and relevant institution, known for its influential role in shaping the direction of art historical research. Since her arrival in 1995, the worlds of publishing and research have changed dramatically through the information technology revolution. She embraced the situation confidently, fostering projects that advanced the Library’s offerings and abilities, and forging valuable relationships and collaborations with other institutions. Pat Barnett’s legacy is remarkable, and in her wake the Frick Art Reference Library stands solid in its resources, supporters, collections, and future.” ABOUT THE FRICK ART REFERENCE LIBRARY The Frick Art Reference Library was founded in 1920 by Helen Clay Frick as a memorial to her father, Henry Clay Frick (whose art and mansion were bequeathed to the public, later becoming The Frick Collection, one of the world’s most treasured house museums). -

ARCHITECTS Allegheny

InARCHITECTS Allegheny The North Side Work of Notable Architects : A Tour and Exploration 17 April 2010 NEIGHBORHOOD BUILDING/SITE YEAR ARCHITECT Central N.S. Russel Boggs House 1888 Longfellow Alden Harlow Allegheny Commons Commons Design 1876 Mitchell & Grant West Park 1964 Simonds and Simonds Allegheny Center St. Peter’s RC Church 1872 Andrew Peebles Allegheny Post Office 1895 William Martin Aiken Children’s Museum 2004 Koning Eizenberg Buhl Planetarium 1938 Ingham, Pratt & Boyd Allegheny Library 1889 Smithmeyer & Pelz IBM Branch Office 1975 Office of Mies /FCL & Assoc. Allegheny East Osterling Studio 1917 F.J. Osterling Sarah Heinz House 1915 R.M. Trimble Schiller School 1939 Marion M. Steen Workingman’s S.B. 1902 James T. Steen JrOUAM Hall Bldg 1890s? F.J. Osterling Latimer School 1898 Frederick C. Sauer Central N.S. Allegheny General 1930 York & Sawyer Garden Theatre 1914 Thomas H. Scott Engine Co. No.3 1877 Bailey and Anglin Orphan Asylum 1838 John Chislett N.S. Unitarian Church 1909 R.M. Trimble N.S. YMCA 1926 R.M. Trimble Allegheny West B.F. Jones, Jr. House 1908 Rutan & Russell J.C. Pontefract House 1886 Longfellow & Alden Calvary M.E. Church 1893 Vrydaugh Shepherd Wolfe Emmanuel P.E. Church 1885 H.H. Richardson Manchester Union M.E. Church 1866 Barr & Moser Woods Run Western Penitentiary 1876 E.M. Butz R.L. Matthews Dept. 1902 Frederick Scheibler Jr. McClure Ave Presbyt. 1887 Longfellow Alden Harlow 1 WILLIAM MARTIN AIKEN William Aiken (1855–1908) was born in Charleston, South Carolina and edu- cated at The University of the South (1872–1874) where he taught in his last year of attendance and moved to Charleston, S.C. -

Summer 2021 at | Cmu.Edu/Osher W

Summer 2021 at | cmu.edu/osher w CONSIDER A GIFT TO OSHER To make a contribution to the Osher Annual Fund, please call the office at 412.268.7489, go through the Osher website with a credit card, or mail a check to the office. Thank you in advance for your generosity. BOARD OF DIRECTORS CURRICULUM COMMITTEE OFFICE STAFF Allan Hribar, President Stanley Winikoff (Curriculum Lyn Decker, Executive Director Jan Hawkins, Vice-President Committee Chair & SLSG) Olivia McCann, Administrator / Programs Marcia Taylor, Treasurer Gary Bates (Lecture Chair) Chelsea Prestia, Administrator / Publications Jim Reitz, Past President Les Berkowitz Kate Lehman, Administrator / General Office Ann Augustine, Secretary & John Brown Membership Chair Maureen Brown Mark Winer, Board Represtative to Flip Conti CATALOG EDITORS Executive Committee Lyn Decker (STSG) Chelsea Prestia, Editor Rosalie Barsotti Mary Duquin Jeffrey Holst Olivia McCann Anna Estop Kate Lehman Ann Isaac Marilyn Maiello Sankar Seetharama Enid Miller Raja Sooriamurthi Diane Pastorkovich CONTACT INFORMATION Jeffrey Swoger Antoinette Petrucci Osher Lifelong Learning Institute Randy Weinberg Helen-Faye Rosenblum (SLSG) Richard Wellins Carnegie Mellon University Judy Rubinstein 5000 Forbes Avenue Rochelle Steiner Pittsburgh, PA 15213-3815 Jeffrey Swoger (SLSG) Rebecca Culyba, Randy Weinberg (STSG) Associate Provost During Covid, we prefer to receive an email and University Liaison from you rather than a phone call. Please include your return address on all mail sent to the Osher office. Phone: 412.268.7489 Email: [email protected] Website: cmu.edu/osher ON THE COVER When Andrew Carnegie selected architect Henry Hornbostel to design a technical school in the late 1890s, the plan was for the layout of the buildings to form an “explorer’s ship” in search of knowledge. -

The Progressive Pittsburgh 250 Report

Three Rivers Community Foundation Special Pittsburgh 250 Edition - A T I SSUE Winter Change, not 2008/2009 Social, Racial, and Economic Justice in Southwestern Pennsylvania charity ™ TRCF Mission WELCOME TO Three Rivers Community Foundation promotes Change, PROGRESSIVE PITTSBURGH 250! not charity, by funding and encouraging activism among community-based organiza- By Anne E. Lynch, Manager, Administrative Operations, TRCF tions in underserved areas of Southwestern Pennsylvania. “You must be the change you We support groups challeng- wish to see in the world.” ing attitudes, policies, or insti- -- Mohandas Gandhi tutions as they work to pro- mote social, economic, and At Three Rivers Community racial justice. Foundation, we see the world changing every day through TRCF Board Members the work of our grantees. The individuals who make up our Leslie Bachurski grantees have dedicated their Kathleen Blee lives to progressive social Lisa Bruderly change. But social change in Richard Citrin the Pittsburgh region certainly Brian D. Cobaugh, President didn’t start with TRCF’s Claudia Davidson The beautiful city of Pittsburgh (courtesy of Anne E. Lynch) Marcie Eberhart, Vice President founding in 1989. Gerald Ferguson disasters, and nooses show- justice, gay rights, environ- In commemoration of Pitts- Chaz Kellem ing up in workplaces as re- mental justice, or animal Jeff Parker burgh’s 250th birthday, I was cently as 2007. It is vital to rights – and we must work Laurel Person Mecca charged by TRCF to research recall those dark times, how- together to bring about lasting Joyce Redmerski, Treasurer the history of Pittsburgh. Not ever, lest we repeat them. change. By doing this, I am Tara Simmons the history that everyone else Craig Stevens sure that we will someday see would be recalling during this John Wilds, Secretary I’ve often heard people say true equality for all. -

October Parks News | Pittsburgh Parks Conservancy

10/8/2020 October Parks News | Pittsburgh Parks Conservancy october parks news To explore the dozens of events coming to your local parks this month, read below. Click here to explore our events calendar. https://preview.hs-sites.com/_hcms/preview/content/14924728214?portalId=415693&_preview=true&cacheBust=0&preview_key=fmeSffiC&from_buffer=false&__… 1/7 10/8/2020 October Parks News | Pittsburgh Parks Conservancy celebrate fall with guided nature hikes You can register here for October's First Friday Nature Walk, Third Friday Fitness Hike, and Hike with a Naturalist. This month, naturalist educators will be discussing themes of Fall and showcasing all the ways in which our parks and paths change with every season. During the family-friendly Hike with a Naturalist, kids and families can participate in a leaf scavenger hunt and craft activity. frick park after dark wraps up its first season Thank you for the support you've shown to the Frick Park After Dark series! We're wrapping up our first FPAD season with an indoor workshop hosted by Third Day, live music by Rhythm and Steel, food from Revival Chili Food Truck, and adult beverages from Wigle Whiskey. Purchase tickets here → https://preview.hs-sites.com/_hcms/preview/content/14924728214?portalId=415693&_preview=true&cacheBust=0&preview_key=fmeSffiC&from_buffer=false&__… 2/7 10/8/2020 October Parks News | Pittsburgh Parks Conservancy parks listening tour II: the parks plan continues Phase Two of the Listening Tour details the plans for improved park safety, increased fair funding and access, and upgraded maintenance and facilities for all existing city parks. -

May–June 2015 You Continue to Improve Mellon Square Downtown

www.pittsburghparks.org May–June 2015 You continue to improve Mellon Square downtown Park edges get a facelift to frame a masterpiece ast summer you Lcompleted the restoration of downtown’s modernist park masterpiece. Today, the improvement of the “Square in the Triangle” continues as the project moves to the streetscape of this unique city block. “Mellon Square was designed from curb-to- Scott Roller credit photo curb. It integrates a park, retail stores, and a parking garage,” says Pittsburgh Parks Conservancy Parks Curator Susan Rademacher. “Every square inch of this world- “People should be proud of a design can experience relaxation, renowned place should be that serves us all so well. We are.” renewal and reunion with special.” – Dylan, Talbott, and Henry Simonds the natural world. People should be proud of a ellon Square’s design that serves us all so Mstreetscape on new interpretive wall and Dylan, Talbott, and Henry well. We are,” they said. Smithfield Street will get a Aan illuminated signband Simonds, the grandsons of total facelift with brand-new overhead have already been Mellon Square’s designer ublic and private curbing, sidewalk planters, completed. It alerts people John Ormsbee Simonds, Ppartners continue to benches, as well as trash to Mellon Square’s presence funded the creation of the be identified to secure receptacles. The storefronts above and provides a brief interpretive wall. “This garden the needed resources along the street will be history of Pittsburgh’s first plaza is an oasis of calm and for this plan to be updated and streamlined. Renaissance and the park. -

Urban Essay Fall 06 Website.Pub

University of Pittsburgh’s Urban Studies Association Newsletter Issue 13 October 2005 T HE PRESIDENT’ S A DDRESS My fellow Urbanites— We’re back! The urbanSA (yes, we had a branding change this year) is starting Fall 2005 renewed and ready to explore the city again. After a mid-summer planning session with officers, alumni, and current members, the urbanSA is setting up its first strategic plan to make sure we’re sustain- able enough for years to come. Put your two cents into our strategic plan by taking our first-ever online survey, available from our website’s front page. Your opinion will affect how we plan our events in the not-so-distant future. And speaking of events... We know how much you heart getting out into town. So TRACKS OF STEEL: LIGHT far, we’ve set up Oakland cleanups with the Oakland Planning and Development Corporation’s Adopt-a-Block program, an- R AIL IN PITTSBURGH other work day with Habitat for Humanity’s Panther Chapter B Y PATRICK SINGLETON (which was a huge success even in last winter’s 19-degree weather), a tour of Regent Square, with more tours of East One of the most hotly contested issues recently is, not surprisingly, Liberty and other hotspots in the East End in the works, plus a government spending on a transportation project. This time, it is a light talk with Boldly Live Where Others Won’t author Mark Harvey rail extension to the T termed the North Shore Connector. With both Smith and a screening of the End of Suburbia.