Studies in Applied Economics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

District Heating in Bulgaria

STATE ENERGY REGULATORY COMMISSION - BULGARIA DistrictDistrict heatingheating inin BulgariaBulgaria TOMA GIORTCHEV commissioner May 18-24, 2002 Newark, New Jersey – Washington, DC, U.S.A. STATE ENERGY REGULATORY COMMISSION - BULGARIA DistrictDistrict heatingheating inin BulgariaBulgaria ¾ 21 District heating companies ¾ 9 companies with combined heat and power production ¾ More than 40 years experience ¾ 570 000 dwellings ¾ 1.650 mill. People – 20% of population ¾ Public buildings with a heating volume equal to 240 000 normal dwellings May 18-24, 2002 Newark, New Jersey – Washington, DC, U.S.A. STATE ENERGY REGULATORY COMMISSION - BULGARIA DistrictDistrict heatingheating companiescompanies inin BulgariaBulgaria ROMANIA RUSE Pleven A I Shumen Varna Veliko Tarnovo SERB Sofia Sliven Pernik Burgas BLACK SEA Stara Zagora Pazardjik Plovdiv Blagoevgrad Legend TURKEY RS DHC @A INDUSTRIAL PP @A Nuclear PP - @A THERMAL PP GREECE STATE ENERGY REGULATORY COMMISSION - BULGARIA HeatHeat andand powerpower productionproduction fromfrom CHPCHP ¾ 1900 GWh/year power production ¾ 12 000 GWh/year heat production ¾ 1,4 billion m3 natural gas ¾ 1 million tones of coals ¾ 160 000 tones of heavy fuel oil ¾ 18 % transmission losses May 18-24, 2002 Newark, New Jersey – Washington, DC, U.S.A. STATE ENERGY REGULATORY COMMISSION - BULGARIA CompaniesCompanies withwith combinedcombined heatheat andand powerpower productionproduction 25 21 20 15 11 10 9 5 0 DHC-total DHC-with Industrial May 18-24, 2002 CHP PP Newark, New Jersey – Washington, DC, U.S.A. STATE ENERGY REGULATORY COMMISSION - BULGARIA SharesShares ofof CHPCHP companiescompanies inin powerpower productionproduction ((installedinstalled capacitiescapacities)) 5% 8% DHC with CHP 29% Industrial PP 36% Thermal PP 22% HPS over 5 MW Nuclear Power plant May 18-24, 2002 Newark, New Jersey – Washington, DC, U.S.A. -

Transport and Logistics in Bulgaria

Investing in your future EUROPEAN UNION OP “Development of the Competitiveness of the Bulgarian European Regional Economy” 2007-2013 Development Fund Project “Promoting the advantages of investing in Bulgaria” BG 161PO003-4.1.01-0001-C0001, with benefi ciary InvestBulgaria Agency, has been implemented with the fi nancial support of the European Union through the European Fund for Regional Development and the national budget of the Republic of Bulgaria. TRANSPORT AND LOGISTICS IN BULGARIA CONTENTS 1. Introduction 4 2. Overview of Bulgaria 10 3. Overview of the Transport& Logistics sector 14 4. Human Resources 45 5. Success Stories 53 Introduction Bulgaria is ideally located to provide easy access to Turkey, and the Middle East 4 Introductiont the markets in Europe, Russia, the CIS countires, BULGARIA is a member of the EUROPEAN UNION which stands for FREE MOVEMENT OF GOODS FIVE PAN-EUROPEAN CORRIDORS pass through the country TRACECA (TRAnsport Corridor Europe – Caucasus – Asia) links Bulgaria with Central Asia Source: InvestBulgaria Agency 5 Introduction Bulgaria offers easy access to the EU, Russia and the CIS countries, and the Middle East at the same time City Sofi a Belgrade Budapest Distance Days by Distance Days by Distance Days by (km) truck (km) truck (km) truck European Union Munich 1 097 3 773 2 564 1 Antwerp 1 711 4 1 384 3 1 137 2 Milan 1 167 3 885 2 789 1 Piraeus 525 1 806 2 1 123 3 Russia and CIS Moscow 1 777 5 1 711 5 1 565 5 Kiev 1 021 4 976 3 894 3 Middle East Istanbul 503 1 809 2 1 065 3 Kuwait City 2 623 12 2 932 13 3 -

Bulgaria Service Centers / Updated 11/03/2015

Bulgaria Service Centers / Updated 11/03/2015 Country Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria CAD R&D CAD R&D CAD R&D CAD R&D DASP name Progress Progress Progress Progress Center Center Center Center Sofia 1574 69a Varna 9000 Varna 9000 Burgas 8000 Shipchenski Slivntisa Blvd Kaymakchala Konstantin Address (incl. post code) and Company Name prohod blvd. 147 bl 19A n Str. 10A. Velichkov 34, CAD R&D appt. Flysystem 1 fl. Kontrax Progress Vizicomp Center Country Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria City Sofia Varna Varna Burgas General phone number 02 870 4159 052 600 380 052 307 105 056 813 516 Business Business Business Business Opening days/hours hours: 9:00– hours: 9:00– hours: 9:00– hours: 9:00– 17:30 17:30 17:30 17:30 Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria CAD R&D CAD R&D CAD R&D CAD R&D CAD R&D CAD R&D CAD R&D CAD R&D CAD R&D Progress Progress Progress Progress Progress Progress Progress Progress Progress Center Center Center Center Center Center Center Center Center Ruse 7000 Shumen Stara Zagora Plovdiv 4000 Burgas 8000 Pleven 5800 Sliven 8800 Pernik 2300 Burgas 8000 Tsarkovna 9700 Simeon 6000 Ruski Bogomil Blvd Demokratsiy San Stefano Dame Gruev Krakra Str Samouil 12A. Nezavisimost Veliki Str 5. Blvd 51. 91. Pic a Blvd 67. Str 30. Str 30. Best 68. Krakra Infostar Str 27. SAT Com Viking Computer Pic Burgas Infonet Fix Soft Dartek Group Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Bulgaria Burgas Stara Zagora Plovdiv Burgas Pleven Ruse Sliven Pernik Shumen 056 803 065 042 -

2017 National

FEDERATION SVIP S P O R T F O R V I S U A L L Y I M P A I R E D P E O P L E P R O T O K O L from Bulgarian National Tournament of Shoudown – Men Varna, Bulgaria, 21-24.09.2017 In the period from September 21 until September, 24, 2017, in the School for Visually Impaired Students “Prof. Ivan Shishmanov”, Varna, Bulgaria, was held the Bulgarian National Tournament of Showdown (Men and Women). In the tournament took part players from following sport clubs. (Abbreviations and the names of the clubs are transliterated from the sound in Bulgarian language, to be easy to find information in the internet about them, if any): 1. SKI „Atlet" - Varna 2. OSKSG „Vihar" - Varna 3. SKI „Vitosha" - Sofia 4. SK „Dostoen Zhivot" - Blagoevgrad 5. SKHU „Dorostol 2011" - Silistra 6. SKHZU „Pautalia Sport - 2005” - Kyustendil 7. SKHU „Pirin Sport - 2013" - Blagoevgrad 8. SKS „Uspeh" - Varna 9. SK “Uspeh” - Sofia 10. USK “Bolid” - Sofia 11. SKI „Dunav 2013” - Ruse 12. SKI „Krakra” - Pernik Final Standing – Men – Group A 1. Kostadin Dimitrov SKI „Atlet“ - Varna 2. Veselin Kushnerenkov SKI „Vitosha“ - Sofia 3. Teodor Stoyanov SKI „Vitosha“ - Sofia 4. Hristomir Pandov SKI „Vitosha“ - Sofia 5. Sedat Musin SKHU „Dorostol 2011“ - Silistra 6. Gospodin Stoyanov SKI „Atlet“ - Varna 7. Bonyo Bonchev OSKSG „Vihar“ - Varna 8. Dobromir Udrev SKHU „Dorostol 2011“ - Silistra 9. Mariyan Kolev SKI „Atlet“ - Varna 10. Vasil Todorov SK „Dostoen Zhivot“ - Blagoevgrad 11. Lyubomir Trayanov SKHU „Pirin Sport - 2013“ - Blagoevgrad 12. Borislav Lazarov SKHZU „Pautalia Soirt - 2005“ - Kyustendil Final Standing – Men – Group B 1. -

Prevalence of HBV and HCV Markers in Blood Donors in Bulgaria

Prevention of viral hepatitis transmission through blood transfusions V. Yordanova, S. Bakalova, K. Zlidolska VHPB, Sofia, 23-24.03.2011 BLOOD TRANSFUSION SYSTEM • National Center of Transfusion Hematology • 4 Regional Blood Establishments Full activities • 23 Hospital - based Blood Establishments Collection, storage, distribution, patients testing BLOOD TRANSFUSION SYSTEM NCTH RCTH DTH ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE MoH NCTH RCTH RCTH RCTH RCTH Sofia Plovdiv St.Zagora Pleven Varna 7 HB - BTC 4 HB - BTC 3 HB - BTC 5 HB - BTC 44 HBHB -- BTCBTC HBV and HCV markers in donors from Sofia region HBsAg positive donors Donors of Number HBsAg Percentage positive NCTH 34682 473 1.36 Sofia region 4391 66 1.50 Blagoevgrad 5230 175 3.34 Vratza 2442 27 1.10 Vidin 1702 17 1.00 Kjustendil 2095 36 1.71 Lom 1933 27 1.39 Pernik 1316 18 1.36 MMA 5367 93 1.73 Total 59158 932 1.57 Percentages of HBsAg positive donors • Males - 1.62 • Жени – 1.41 • NCTH – 1.43 • NCTH - 1.14 • Sofia region – 1.48 • Sofia region – 1.57 • Blagoevgrad – 3.30 • Blagoevgrad – 3.50 • Vratza – 1.12 • Vratza – 1.05 • Vidin – 1.04 • Vidin – 0.83 • Kjustendil – 1.60 • Kjustendil – 2.17 • Lom – 1.58 • Lom – 0.91 • Pernik – 1.32 • Pernik – 1.59 • MMA – 1.74 • MMA – 1.68 HBsAg positive donors • Females – 21.1% - mean 1.41% • Males – 78.9% - mean 1.62% • Mean for the country – 2.72 % • Range • 1.0% • 6.65% • Correlation with moslem population HCV positive donors Donors of Number HCV Percentage positive NCTH 38247 89 0.23 Sofia region 5714 16 0.28 Blagoevgrad 6431 16 0.25 Vratza 2785 4 0.14 Vidin -

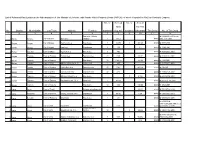

List of Released Real Estates in the Administration of the Ministry Of

List of Released Real Estates in the Administration of the Ministry of Defence, with Private Public Property Deeds (PPPDs), of which Property the MoD is Allowed to Dispose No. of Built-up No. of Area of Area the Plot No. District Municipality City/Town Address Function Buildings (sq. m.) Facilities (decares) Title Deed No. of Title Deed 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Part of the Military № 874/02.05.1997 for the 1 Burgas Burgas City of Burgas Slaveykov Hospital 1 545,4 PPPD whole real estate 2 Burgas Burgas City of Burgas Kapcheto Area Storehouse 6 623,73 3 29,143 PPPD № 3577/2005 3 Burgas Burgas City of Burgas Sarafovo Storehouse 6 439 5,4 PPPD № 2796/2002 4 Burgas Nesebar Town of Obzor Top-Ach Area Storehouse 5 496 PPPD № 4684/26.02.2009 5 Burgas Pomorie Town of Pomorie Honyat Area Barracks area 24 9397 49,97 PPPD № 4636/12.12.2008 6 Burgas Pomorie Town of Pomorie Storehouse 18 1146,75 74,162 PPPD № 1892/2001 7 Burgas Sozopol Town of Atiya Military station, by Bl. 11 Military club 1 240 PPPD № 3778/22.11.2005 8 Burgas Sredets Town of Sredets Velikin Bair Area Barracks area 17 7912 40,124 PPPD № 3761/05 9 Burgas Sredets Town of Debelt Domuz Dere Area Barracks area 32 5785 PPPD № 4490/24.04.2008 10 Burgas Tsarevo Town of Ahtopol Mitrinkovi Kashli Area Storehouse 1 0,184 PPPD № 4469/09.04.2008 11 Burgas Tsarevo Town of Tsarevo Han Asparuh Str., Bl. -

Bulgaria Strumento: Ottenimento Delle Prove Tipo Di Competenza: Autorità Competente Queste Informazioni Potrebbero Non Essere Aggiornate

IT Pagina iniziale Paese: Bulgaria Strumento: Ottenimento delle prove Tipo di competenza: Autorità competente Queste informazioni potrebbero non essere aggiornate. Il paese che le ha fornite (Bulgaria) le sta aggiornando. In base alle informazioni da voi fornite è stato individuato più di un tribunale/autorità competente per questo strumento giuridico. Segue elenco: Okrazhen sad Blagoevgrad 1 Vassil Levsky St. Città/Comune : Blagoevgrad CAP : 2700 (+359-73) 88 98 40 (+359-73) 83 03 96 [email protected] https://blagoevgrad-os.justice.bg Okrazhen sad Burgas 101 Alexandrovska St. Città/Comune : Burgas CAP : 8000 (+359-56) 879 400 (+359-56) 811 136 [email protected] http://www.osburgas.org Okrazhen sad Dobrich 7 Konstantin Stoilov St. Città/Comune : Dobrich CAP : 9300 (+359-58) 652 030 (+359-58) 601 480 [email protected] http://dobrichrs.court-bg.org Okrazhen sad Gabrovo 1 Vazrazhdane St. Città/Comune : Gabrovo CAP : 5300 (+359-66) 811 110 (+359-66) 804 679 [email protected] http://www.court-gbr.com Okrazhen sad Haskovo 144 Bulgaria Blvd. Città/Comune : Haskovo CAP : 6300 (+359-38) 60 18 14 (+359-38) 60 18 34 [email protected] http://okrsud.haskovo.net Okrazhen sad Kardzhali 48 Belomorska St. Città/Comune : Kardzhali CAP : 6600 (+359-361) 62703 (+359-361) 62708 [email protected] http://www.kardjali.justice.bg Okrazhen sad Kyustendil 31 Gorotzvetna St. Città/Comune : Kyustendil CAP : 2500 (+359-78) 550455; (+359-78) 550464 (+359-78) 550468 [email protected] http://kjustendil.court-bg.org Okrazhen sad Lovech 41 Targovska St. Città/Comune : Lovech CAP : 5500 (+359-68) 68 98 98 (+359-68) 64 89 02 [email protected] http://www.lovech.court-bg.org Okrazhen sad Montana 24 Vassil Levsky St. -

Bulgaria Page 1 of 6

Bulgaria Page 1 of 6 Bulgaria International Religious Freedom Report 2007 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor The Constitution provides for freedom of religion; however, the law prohibits the public practice of religion by unregistered groups. The Constitution also designates Eastern Orthodox Christianity as the "traditional" religion. There was no change in the status of respect for religious freedom by the Government during the period covered by this report, and government policy contributed to the generally free practice of religion. There were some reports of societal abuses or discrimination based on religious belief or practice. Discrimination, harassment, and general public intolerance, particularly in the media, of some religious groups remained an intermittent problem. The U.S. Government discusses religious freedom issues with the Government as part of its overall policy to promote human rights. Section I. Religious Demography The country has an area of 42,855 square miles and a population of 7.7 million. The majority of citizens, estimated at 85 percent, identify themselves as Orthodox Christians. Muslims comprise the largest minority, estimated at 13 percent; other minorities include Catholics, Protestants, Jews, Gregorian-Armenian Christians, and others. Among the ethnic-Turkish minority, Islam is the predominant religion. Academic research estimated that up to 40 percent of the population is atheist or agnostic. Official registration of religious organizations is handled by the Sofia City Court; it reported that 12 new denominations were registered between February 2006 and February 2007, bringing the total number of registered religious groups to 85 denominations in addition to the Bulgarian Orthodox Church (BOC), an increase of more than 15 percent. -

Bulgargaz in the New SEE Gas Scene Nikolay MILEV Head of R&D Division, Bulgargaz EAD Phd, Assoc.Prof., Petroleum Engineering, Economics

INTERNATIONAL ENERGY AGENCY ENERGY CHARTER SECRETARIAT Gas Seminar in SE Europe: Investment, Transit, Trade Bulgargaz in the new SEE gas scene Nikolay MILEV Head of R&D Division, Bulgargaz EAD PhD, Assoc.prof., Petroleum Engineering, Economics Istanbul, May 5-6, 2004 Focused on • Bulgargaz: in brief • Local market development strategy • New Energy Act: Bulgargaz market positioning • Bulgargaz: International dimension Gas Market Players • Bulgargaz • 28 small scale GDC in 33 municipalities • 2 production companies NATIONAL GAS TRANSMISSION NETWORK CS Kardam 2 CS Kardam 1 ROMANIA Gen. Toshevo Kubrat Dobrich Isperih Russe Montana UGS + CS Chiren Varna Biala Razgrad Pleven Levski CS Provadia Vratza Roman YUGOSLAVIA CS Polski Senovetz Lovech Turgoviste Sofia Zlatna Panega Sevlievo Botevgrad Sliven Burgas Pernik CS Lozenetz Elin Pelin Stara Zagora Debelt Iambol Rakovski Nova Zagora CS Ihtiman CS Strandja Plovdiv Pazardjik Parvomaj Dimitrovgrad Asenovgrad TURKEY Haskovo Legend: CS Petrich Main gas pipeline Gas pipeline branch Transit gas pipeline Compressor station GREECE Gas reduction station Indigenous Gas Production 2003 120,0% 99,6% 100,0% 80,0% 60,0% 40,0% 20,0% 0,4% 0,0% Import Indigenous Bulgargaz: x TSO & Whole Supplier x Vertically integrated company x 100 % state owned x Licensed for: - transmission within Bulgaria - transit - storage - distribution Bulgargaz at Present Deals with: % Import (single source) 100 Production 0 Supply 100 Transmission 100 Transit 100 Storage 100 Distribution 0.004 Bulgargaz: Strategic Axis • Local -

Pernik Municipality Bulgaria

Pernik Municipality Bulgaria PERNIK MUNICIPALITY ` Pernik Municipality is located ` to the south-west of Bulgaria. ` Pernik town is a regional centre. ` The tota l sur face of th e M uni ci pali ty i s ` About 484 sq. m. ` The population numbers 100 000 inhabitants. Pernik Municipality, Sofia Region, is only 30km0 km southeast of Sofia. Pernik is close to: ` transport corridors 8 and 4; ` motorway Sofia- Pernik -Tran -Serbia; ` motorway Sofia- Pernik- Kyustendil - Skopie; ` motorway Sofia- Pernik -Blagoevgrad -Thessaloniki; ` Sofia-Blagoevgrad -Greece railway; ` and 40 km away from Sofia International Airport; ` M“Lli”idiMotorway “Lyulin” is under construction. Pernik municipality was one of the largest industrial zones in Bulgaria during the 80s of the last century. Metallurgy; machinery construction; electric industry; coal production; energy and others were subject to deliberate and fast development. The economy of Pernik started to transform after 1989. The huge industrial factories lost their economic importance, and some of them completely stopped their activities. A change of the property ownership in the economic sector was made during the last 17-18 years. Most of the industrial factories were privatized and thus, being private property, a process of modernization and renovation occurred. Globalization and the compppetiveness’ pressure on the economy were created: new productions; new technologies; new knowledge; new workforce qualification. Political will for support the bussines in Pernik municippyality has been ex pressed. Pernik Municipality developed a “Plan for development of Pernik Municipality 2007-2013” according to Law Regional development. The main priorities were concentrated in a few directions: Business stimulating and facilitating; Infrastructure and environment improvement; Improving the quality of human capital. -

Bulgaria 2000

TEAM FOR THE PREPARATION OF NATIONAL HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT BULGARIA 2000 National Coordinator Adviser, Human Development Strategy Unit Dr. Andrey Ivanov Gerardo Berthin Contributors Dr. Antony Todorov, Dr. Belin Mollov, Dr. Dotcho Mihaylov, Dr. Georgi Ganev, Dr. Julia Spiridonova, Dr. Mikaela Vazharova, Dr. Vassil Marinov and Luchesar Bogdanov Statistical Team Micho Chipev, Prof. Yordan Venedikov, Sergey Tzvetarski, Stoyan Tzvetkov and Todor Todorov STRATEGIC PARTNERSHIPS OF NATIONAL HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT BULGARIA 2000 National Statistical Institute National Center for Regional Development and Housing Policy National Association of Municipalities in the Republic of Bulgaria Friedrich Ebert Foundation, Sofia-Bulgaria ADVISORY COMMITTEE OF NATIONAL HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT BULGARIA 2000 Svetlana Alexandrova, New Bulgarian University; Friedrich Bauersachs, Institute for Market Economics; Bisserka Benisheva, Ministry of Foreign Affairs; Mark Bossani, Ethnic Initiative for Human Rights Foundation; Vincenzo Celeste, Embassy of Italy; Ginka Chavdarova, National Association of Municipalities; Vera Dakova, Ideas in Process; Romain Darbelley, Embassy of Switzer- land; Hristo Hristozov, European Law Society; Pentcho Houbtchev, Friedrich Ebert Foundation; Ginka Kapitanova, Foundation for Local Government Reform; Christos Makridis, European Union Delegation; Fernando Nogales, Embassy of Spain; Jorge Nieto, European Union Delegation; Ivanka Petkova, Institute for Economic Policy; Kaye Pyle, United States Agency for International Development;Valery -

TOURISM VALUE CHAIN DIAGNOSIS Cross Border Area Elin Pelin Bulgaria and Leskovac Serbia

Interreg - IPA CBC Bulgaria – Serbia Programme CCI Number 2014TC16I5CB007 Project - The Magic of Synergies - Ref. No CB007.2.12.002 Study TOURISM VALUE CHAIN DIAGNOSIS cross border area Elin Pelin Bulgaria and Leskovac Serbia -Pathways to Prosperity- Place: Elin Pelin & Leskovac Data: February 2021 DISCLAIMER This document has been produced with the assistance of the European Union through the Interreg-IPA CBC Bulgaria-Serbia Programme, CCI No 2014TC16I5CB007. The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of The Centre for Development Jablanica and Pcinja Districts and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union or the Managing Authority of the Programme. ОБЩИНА ЕЛИН ПЕЛИН The project is co-funded by EU through the Interreg-IPA CBC Bulgaria–Serbia Programme. The project The Magic of Synergy (№ CB007.2.12.002) within the Interreg – IPA program for the cross-border collaboration Bulgaria- Serbia 2014-2020 e-publication: Tourism Value Chain Diagnosis-cross border area Elin Pelin Bulgaria and Leskovac Serbia Publication type: A study Publisher: The Centre for the Development of Jablanica and Pcinja Districts (Project partner 3) Authors: Project team members: • Dobrila Sudimac Martinović (Researcher) • Goran Milenković (Facilitator) The use and publication of the information and parts of the text for non-commercial, non-profit, or scientific purposes is allowed with accurate source citing. Elin Pelin and Leskovac February 2021 2 Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations .........................................................................................................................