1 the Balfour Declaration's Territorial Landscape: Between Protection and Self Determination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Firkowicz, Forgeries and Forging Jewish Identities

chapter 9 On Firkowicz, Forgeries and Forging Jewish Identities Dan D.Y. Shapira This paper is a—necessarily short—report on the great project of the publica- tion of forged tombstone inscriptions in a Crimean Jewish-Karaite cemetery, by which (together with other spurious evidence) Avraham Firkowicz (1787– 1874) attempted to establish a myth of the origin of the Karaite Jews. In order to appreciate his efforts it is necessary to briefly sketch the various trends of ideas among Jews and Gentiles on the ancient history of Hebrews as current in the early nineteenth century in Russia and elsewhere. Avraham, son of Shemuel Firkowicz, was to a large degree a medieval char- acter. Born in 1787 in Łuck (Lutsk, Lutzk; Volhynia) in a tiny Turkic-speaking community of Jewish religious dissidents, the Karaites, as a subject of the Polish- Lithuanian Commonwealth, in the epoch of the early Jewish Enlightenment, he lived through the emergence of the Jewish Reform Movement, the heyday of the Wissenschaft des Judenthums, and the emergence of both the specific Russian-Jewish civilization and Yiddish literature. He died in 1874 after an active life up to his last day, only a few years before the Pogroms of 1881–82 which prompted the massive Jewish emigration to America, the emergence of the first Palestinophile (or proto-Zionist) organizations and the important book Autoemancipation by Leon Pinsker, the son of a friend and colleague of his, Śimhah Pinsker. When young Firkowicz began to read his Hebrew Pentateuch, he found himself under Russian rule, following the third partition of Poland in 1795. -

CURRICULUM VITAE JAMES E. CRONIN Visiting Scholar, CERI

CURRICULUM VITAE JAMES E. CRONIN Department of History Boston College Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts 02167 (617) 552-3798 Fax: 552-2478 E-Mail: [email protected] Ph.D., Comparative History, Brandeis University, 1977 Academic Experience Professor, 1986-, Department of History, Boston College Faculty Affiliate, Minda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies, Harvard University, 1987-; chair/co-chair, British Study Group, 1987-2014 Visiting Professor, University of Pavia, Department of Political and Social, October 11-21, 2015 Visiting Scholar, CERI (Centre d’Etudes des Recherches Internationales), Sciences Po, Paris, October-December, 2015 Visiting Fellow, Centre for Contemporary British History, Institute of Historical Research and Institute for the Study of the Americas, School of Advanced Study, University of London, January-June, 2007 Visiting Scholar, Center for the Study of Industrial Societies, University of Chicago, 1985-86 Professor, 1985-86; Associate Professor, 1981-85; and Assistant Professor, 1976-81; Department of History and Doctoral Program in Urban Social Institutions, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Fellowships, Grants and Awards Fellow of the Royal Historical Society Earhart Foundation Research Fellowship, 2008 Marion and Jasper Whiting Research Fellowship, 2007 Benjamin Meaker Professor, University of Bristol, 2002 Distinguished Research Award, Boston College, 1999 Boston College Research and Teaching Grants: Research Incentive Grant, 1998; Research Expense Grants, 1987, 1988, 1989, 1992, 1997, 2000, 2003; Teaching Grant, 1990 German Marshall Fund of the United States, Research Fellowship, 1985-86 Center for Twentieth Century Studies, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Research Fellow, 1983-84 Award for Excellence in Research, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Foundation, 1982 National Endowment for the Humanities, Research Fellowship, 1981 American Council of Learned Societies, Research Fellowship, 1980 Prize for "Best Article," Journal of Social History. -

Eliezer Schweid: an Intellectual Portrait

ELIEZER SCHWEID: AN INTELLECTUAL PORTRAIT Leonard Levin Prelude: The Background of Spiritual Zionism Eliezer Schweid will be remembered to posterity as the voice and con- science of spiritual Zionism (especially its Gordonian variant) in the age of the fulfillment of the State and the onset of postmodernism. To shed light on this characterization, I will first provide a historical sketch to situate “spiritual Zionism” within the panorama of modern Jew- ish ideological movements. Jewish thought has always presented a per- petual dialectic of universalistic and particularist themes and tendencies. In the modern period, the pioneers of modern Judaism—thinkers such as Moses Mendelssohn, Abraham Geiger, and Samson Raphael Hirsch— first responded to the Western Enlightenment, a universalistic move- ment within modern Western thought, by emphasizing the universalistic themes of Judaism, in order to justify Judaism’s existence in the modern world. In effect, their philosophies were a continuation of the medieval Jewish-Christian disputation in modern guise, arguing that Judaism was perhaps the highest representation of the universal monotheistic religion at the heart of Western culture, or at the very least a worthy exemplar of it. Thus, for them the task of Jewish philosophy was to articulate the world- view of the Jewish religion in terms that were intellectually respectable by the standards of the Western philosophical tradition. This task assumed a common intellectual consensus: that all discussants agreed that some form of the Western biblical monotheistic religion was normative, and that Jewish existence was defined religiously as adherence to the Jewish religion, which was a variety of Western biblical monotheistic religion. -

Copy of Copy of IHS ED GUIDE TEMP WIZ

WHAT IS ZIONISM? Section 1: Additional Resources Anita Shapira, Israel: A History, Part 1, Chapter 1 Arthur Herzberg, The Zionist Idea, Introduction Gil Troy, The Zionist Ideas, Introduction Jewish Virtual Library, “Israel: Zionism,” https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/zionism Micah Goodman, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IkBYF4KAir8 Daniel Septimus, https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/questioning-zionism/ Zack Beauchamp, “What is Zionism?” https://www.vox.com/2018/11/20/18080010/zionism-israel-palestine Section 2: Discussion Questions Daniel Septimus notes that when Zionism was formed, it was knocked from the Reform left because the Reform movement viewed Judaism as a religion and not a people, and it was knocked from the right because the religious community viewed Zionism as blasphemous because the “Zionists were revolting against God’s will.” If the Jewish people accepted Zionism earlier on, do you think history would have played itself out in the same way or in a different way? One of the fundamental disputes between Jabotinsky and Herzl was on the impact Zionism would have on anti-Semitism. Herzl believed Zionism would end anti-Semitism, while Jabotinsky believed Zionism would serve as a protection from anti-Semitism. While it seems like anti-Semitism is not going away, what role do you see the Jewish state playing in combating anti-Semitism, and who do you think is responsible to stop anti- Semitism? If Zionism can simply be understood as the Jewish national liberation movement, why do you think some people are opposed to the idea of Zionism? Now that Zionism has reached a major goal of developing a Jewish state, what role do you see Zionism playing? All Rights Reserved Jerusalem U Israel Education Media Lab 2018 Section 3: Review 1. -

Beyond the Nation-State: the Zionist Political Imagination from Pinsker to Ben-Gurion'

H-Nationalism Behar on Shumsky, 'Beyond the Nation-State: The Zionist Political Imagination from Pinsker to Ben-Gurion' Review published on Monday, December 9, 2019 Dmitry Shumsky. Beyond the Nation-State: The Zionist Political Imagination from Pinsker to Ben- Gurion. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018. 320 pp. $40.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-300-23013-0. Reviewed by Moshe Behar (University of Manchester) Published on H-Nationalism (December, 2019) Commissioned by Cristian Cercel (Ruhr University Bochum) Printable Version: http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showpdf.php?id=53474 In a thought-provoking, evidence-based study, Dmitry Shumsky sets out to defend one principal contention: that contrary to the prevailing view in both scholarly and activist-oriented circles, the “fathers” of Zionism were far from being interested in the single overriding idea of establishing a (Jewish) state. They instead entertained several alternatives to secure what they understood to be Jewish national life—including a federation, a binational state, or a multinational democratic state comprising Jewish and Arab parliaments. The conceptualization by Zionism’s “fathers” of national self-determination was thus far from being confined to the familiar model of a Jewish nation-state. To appreciate the originality of Shumsky’s quest it is worth noting that scholars of Palestine/Israel ordinarily know something about pre-1948 movements or organizations that offered alternatives to the twin ideas of Palestine’s territorial partition and establishment of a Jewish state. These include organized Sephardic/Mizrahi (non-European) Jews who supported, since the 1908 Young Turk revolution, a shared Jewish-Arab homeland; Brit Shalom (1925-33); Kedma-Mizraha (late 1930s); the Ichud/Union (1942-48); and some Marxist currents that since the early 1940s began to entertain socialist binational arrangements. -

ONE HUNDRED YEARS of ZIONISM: Vision and Reality — Reality and Vision

ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF ZIONISM: Vision and Reality — Reality and Vision ALVIN I, SCHIFF, PH.D. Irving Stone Distinguished Professor of Education, Yeshiva University and Chairman, American Advisory Council, Joint Authority for Jewish Zionist Education As the national liberation feature of Zionism comes to a close, it is time to turn to the historical. Judaic vision of Zionism. Each component—the Hebrew language, the Jewish religious tradition, and the land ofIsraeli-must become operative principles of Jewish life. Then Zionism can become a unifying factor, creating a sense of Jewish peoplehood with a common heritage and a common destiny. wo guiding principles serve as the frame Jews exiled to Babylonia. And, since that Tofreference for this article: (1) the vision time, Jews, young and old, would recite be and the reality of Zionism must be viewed as fore grace after their weekday meals: "By the an historic continuum, and (2) there always waters of Babylon, there we sat and cried has been and continues to be a mutual intrin when we remembered Zion" (Psalms 137:1). sic relationship between Jews in the Diaspora and Jews in Eretz Yisrael concerning the THE VISION OF ZIONISM vision of Zionism and its fulfdlment. AND MESSIANISM The term "Zionism" was first used in 1892 The vision of Zionism, expressed as the by Nathan Birnbaum at a meeting in Vienna coming of the Messiah, suffuses the entire (Laquer, 1972). Yet, the concept of Zionism Judaic tradition. It was this fervent belief that is another matter. The idea of Zionism is lightened the yoke of exile for generations. -

Herzl and Zionism

Herzl and Zionism Binyamin Ze'ev Herzl (1860-1904 ) "In Basle I founded the Jewish state...Maybe in five years, certainly in fifty, everyone will realize it.” Theodor (Binyamin Ze'ev) Herzl, the father of modern political Zionism, was born in Budapest in 1860. He was educated in the spirit of the German-Jewish Enlightenment of the period, learning to appreciate secular culture. In 1878 the family moved to Vienna, and in 1884 Herzl was awarded a doctorate of law from the University of Vienna. He became a writer, a playwright and a journalist. Herzl became the Paris correspondent of the influential liberal Vienna newspaper Neue Freie Presse. Herzl first encountered the antisemitism that would shape his life and the fate of the Jews in the twentieth century while studying at the University of Vienna (1882). Later, during his stay in Paris as a journalist, he was brought face-to-face with the problem. At the time, he regarded the Jewish problem as a social issue Herzl at Basle (1898) (Central Zionist Archives) In 1894, Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish officer in the French army, was unjustly accused of treason, mainly because of the prevailing antisemitic atmosphere. Herzl witnessed mobs shouting "Death to the Jews". He resolved that there was only one solution to this antisemitic assault: the mass immigration of Jews to a land that they could call their own. Thus the Dreyfus case became one of the determinants in the genesis of political Zionism. Herzl concluded that antisemitism was a stable Herzl with Zionist delegation en route to Israel (1898) and immutable factor in human society, which (Israel Government Press Office) assimilation did not solve. -

Introduction Sander L

Á Introduction Sander L. Gilman Theodor Lessing’s (1872–1933) Jewish Self-Hatred (1930) is the classic study of the pitfalls (rather than the complexities) of acculturation. Growing out of his own experience as a middle-class, urban, margin- ally religious Jew in Imperial and then Weimar Germany, he used this study to reject the social integration of the Jews into Germany society, which had been his own experience, by tracking its most radical cases. This early awareness of the impossibility of acculturation into what he saw as an inherently antisemitic world led him early to become a Zion- ist (at least a cultural if not a political Zionist) and concomitantly a ra- bid opponent to the rise of German fascism. A failed academic (because of, in his view, the antisemitic a itudes of both the institutions and the faculty—he was not completely wrong), his writing before and a er World War I spanned the widest readership in Germany, from theater criticism to works on the philosophy of history. As one of the most visi- ble Jewish opponents of the Nazis, he had fl ed immediately a er Hitler’s appointment as chancellor in January 1933 to Czechoslovakia, where in March of that year he was assassinated by German-speaking Nazis. Certainly his work that most captured the a ention of both his contem- poraries and our own world is this study of Jewish antisemitism.1 Lessing’s case studies refl ect the idea that assimilation (the radical end of acculturation) is by defi nition a doomed project, at least for Jews (no ma er how defi ned) in the age of political antisemitism. -

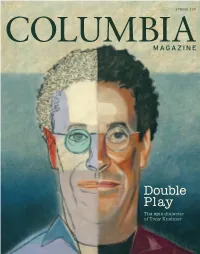

Double Play the Epic Dialectic of Tony Kushner

SPRING 2011 COLUMBIA MAGAZINE Double Play The epic dialectic of Tony Kushner C1_FrontCover2.indd C1 3/25/11 4:22 PM C2_CUClub.indd C2 3/20/11 11:32 AM CONTENTS Spring 2011 62214 DEPARTMENTS FEATURES 3 Letters 14 A Sentimental Education By Paul Hond 6 College Walk Playwright and political activist Meet the Flockers . Feeding the Meter . Tony Kushner provides insight Letter from Brisbane . Hands and Hearts into a key stage of his development. 38 News 22 What Happened to Angkor? Purdy in charge of research . Northwest Corner By David J. Craig Building opens . Alumni at the Oscars . Columbia tree-ring scientists journey Gift launches collaboration between the business to a remote forest in Cambodia to and law schools search for clues about the demise of a civilization. 46 Newsmakers 28 The Arab Reawakening 48 Explorations Tunisia, Egypt, Yemen, Libya, Bahrain, Syria –– and counting. Arab studies 50 Reviews professor Rashid Khalidi discusses the popular revolts reshaping North Africa 62 Classifi eds and the Middle East. 64 Finals 34 Daughter, Lost: A Short Story By Julie Wu ’96PS A mother answers a knock on the door. Cover illustration by Gary Kelley 1-2 ToC.indd 1 3/29/11 12:44 PM IN THIS ISSUE COLUMBIA MAGAZINE Executive Vice President for University Development and Alumni Relations Fred Van Sickle Dustin Rubenstein is an assistant professor in Columbia’s Publisher Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Environmental Jerry Kisslinger ’79CC, ’82GSAS Biology. He received the 2010 American Ornithologists’ Editor in Chief Union Ned K. Johnson Young Investigator Award and the Michael B. -

ORIGINS and EVOLUTION of ZIONISM by Liora Halperin

JANUARY 2015 ORIGINS AND EVOLUTION OF ZIONISM By Liora Halperin Liora R. Halperin is an Assistant Professor in the Department of History and the Program in Jewish Studies at the University of Colorado Boulder. Her research focuses on Jewish cultural history, Jewish-Palestinian relations, language ideology and policy, and the politics surrounding nation formation in Palestine in the years leading up to the creation of the State of Israel in 1948. She is the author of Babel in Zion: Jews, Nationalism and Language Diversity in Palestine, 1920-1948 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2014). In 2012-2013 she was an Assistant Professor of Near Eastern Studies and Judaic Studies at Princeton University Halperin received her Ph.D. from UCLA's history department. This essay is based on a lecture she delivered to FPRI’s Butcher History Institute on “Teaching about Israel and Palestine,” October 25-26, 2014. The Butcher History Institute is FPRI’s professional development program for high school teachers from all around the country. One of the key forces in shaping the history of Palestine was the Zionist movement. This movement emerged from and is rooted in political developments in Europe, but it changed and developed as it evolved from a political movement in Europe to a settlement and nation-building project in Palestine. Thus, we need to step outside the physical context of the Middle East to understand a force that ultimately changed the Middle East. This article focuses on Jewish history and Jewish politics and thought; other texts in this collection complement and complicate the picture I give with perspectives from the Arab, Palestinian, and imperial perspectives. -

A History of Zionism

‘The Invention of a Nation’ — A History of Zionism Independent scholar, Thomas G. Mitchell, discusses the origins of Zionism by reviewing a little-known work, “The Invention of a Nation: Zionist Thought and the Making of Modern Israel” (Columbia University Press, 2003, 289 pp.) by Alain Dieckhoff — a French political sociologist who heads the political science department at Sciences Po (Institut d’études politiques de Paris): The Jews had it much tougher than the other European nationalist movements when it came to obtaining their independence. For one thing, they were scattered throughout Europe, North Africa and the Middle East. Dr. Alain Dieckhoff First, the early Zionists had to convince their fellow Jews that they were a people and a potential nation and that resurrecting that nation was the answer to anti-semitism, which broke out throughout the Russian Empire in the early 1880s in a series of vicious pogroms. Then the Zionists had to decide that their nation should be established in Ottoman Palestine rather than somewhere else. Leon Pinsker, who is normally considered to have been the first Zionist, but was in fact the first Territorialist, argued that the Jews should establish their state anywhere but in the Holy Land. He contended that it was the holiness of the land that had driven the ancient Jews crazy and led to their loss of independence at the hands of the Romans. Theodor Herzl was indifferent as to whether the state should be established in Argentina or elsewhere in South America or in Palestine. But it was the Ostjuden—the Jews of Eastern Europe—who decided for Herzl that the nation-state must be reestablished in Palestine and nowhere else. -

Contesting Imperial Citizenship: the Election of Dadabhai Naoroji As an MP in 1892

CONTESTING IMPERIAL CITIZENSHIP 1 Contesting Imperial Citizenship: The election of Dadabhai Naoroji as an MP in 1892 Jasleen Chaggar Undergraduate Senior Thesis Department of History Columbia University 29 March, 2021 Seminar Advisor: Professor Samuel Roberts Second Reader: Professor Susan G. Pedersen CONTESTING IMPERIAL CITIZENSHIP 2 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank Professor Pedersen, without whose advice and countless re-readings I could not have completed this thesis. Her history course on twentieth century Britain allowed me to re-imagine the place I call home through a historical lens. I must also acknowledge Professor Tiersten, whose course Colonial Encounters, which charted the contact zone between colonial subjects and Western powers, was the inspiration for this study. I would also like to thank Professor Roberts for his wisdom and feedback through this year-long odyssey, as well as the senior thesis seminar “Yellow team” for their incisive comments and constant cheerleading–even through zoom lectures. I owe a great deal of gratitude to my grandparents, who made their own voyage to the metropole in the 1960s and whose relationships to the legacy of Empire have been a continual source of fascination. As always, I would like to thank my family and friends for their ceaseless encouragement and support. CONTESTING IMPERIAL CITIZENSHIP 3 Abstract In 1892, Dadabhai Naoroji became the first Indian elected to British Parliament upon his victory as a Liberal candidate in the Central Finsbury campaign. In the run up and aftermath of his election, the press fiercely debated the candidate’s electability, in column after column which both mirrored and influenced public opinion.