First Occurrence of the Orectolobiform Shark Akaimia in the Oxford Clay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyrighted Material

06_250317 part1-3.qxd 12/13/05 7:32 PM Page 15 Phylum Chordata Chordates are placed in the superphylum Deuterostomia. The possible rela- tionships of the chordates and deuterostomes to other metazoans are dis- cussed in Halanych (2004). He restricts the taxon of deuterostomes to the chordates and their proposed immediate sister group, a taxon comprising the hemichordates, echinoderms, and the wormlike Xenoturbella. The phylum Chordata has been used by most recent workers to encompass members of the subphyla Urochordata (tunicates or sea-squirts), Cephalochordata (lancelets), and Craniata (fishes, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals). The Cephalochordata and Craniata form a mono- phyletic group (e.g., Cameron et al., 2000; Halanych, 2004). Much disagree- ment exists concerning the interrelationships and classification of the Chordata, and the inclusion of the urochordates as sister to the cephalochor- dates and craniates is not as broadly held as the sister-group relationship of cephalochordates and craniates (Halanych, 2004). Many excitingCOPYRIGHTED fossil finds in recent years MATERIAL reveal what the first fishes may have looked like, and these finds push the fossil record of fishes back into the early Cambrian, far further back than previously known. There is still much difference of opinion on the phylogenetic position of these new Cambrian species, and many new discoveries and changes in early fish systematics may be expected over the next decade. As noted by Halanych (2004), D.-G. (D.) Shu and collaborators have discovered fossil ascidians (e.g., Cheungkongella), cephalochordate-like yunnanozoans (Haikouella and Yunnanozoon), and jaw- less craniates (Myllokunmingia, and its junior synonym Haikouichthys) over the 15 06_250317 part1-3.qxd 12/13/05 7:32 PM Page 16 16 Fishes of the World last few years that push the origins of these three major taxa at least into the Lower Cambrian (approximately 530–540 million years ago). -

Database of Bibliography of Living/Fossil

www.shark-references.com Version 16.01.2018 Bibliography database of living/fossil sharks, rays and chimaeras (Chondrichthyes: Elasmobranchii, Holocephali) Papers of the year 2017 published by Jürgen Pollerspöck, Benediktinerring 34, 94569 Stephansposching, Germany and Nicolas Straube, Munich, Germany ISSN: 2195-6499 DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.32409.72801 copyright by the authors 1 please inform us about missing papers: [email protected] www.shark-references.com Version 16.01.2018 Abstract: This paper contains a collection of 817 citations (no conference abstracts) on topics related to extant and extinct Chondrichthyes (sharks, rays, and chimaeras) as well as a list of Chondrichthyan species and hosted parasites newly described in 2017. The list is the result of regular queries in numerous journals, books and online publications. It provides a complete list of publication citations as well as a database report containing rearranged subsets of the list sorted by the keyword statistics, extant and extinct genera and species descriptions from the years 2000 to 2017, list of descriptions of extinct and extant species from 2017, parasitology, reproduction, distribution, diet, conservation, and taxonomy. The paper is intended to be consulted for information. In addition, we provide data information on the geographic and depth distribution of newly described species, i.e. the type specimens from the years 1990 to 2017 in a hot spot analysis. New in this year's POTY is the subheader "biodiversity" comprising a complete list of all valid chimaeriform, selachian and batoid species, as well as a list of the top 20 most researched chondrichthyan species. Please note that the content of this paper has been compiled to the best of our abilities based on current knowledge and practice, however, possible errors cannot entirely be excluded. -

Download This PDF File

Acta Geologica Polonica , Vol. 58 (2008), No. 2, pp. 249-255 When the “primitive” shark Tribodus (Hybodontiformes) meets the “modern” ray Pseudohypolophus (Rajiformes): the unique co-occurrence of these two durophagous Cretaceous selachians in Charentes (SW France) ROMAIN VULLO 1 & DIDIER NÉRAUDEAU 2 1Unidad de Paleontología, Departamento de Biología, Calle Darwin, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Cantoblanco, 28049-Madrid, Spain. E-mail: [email protected] 2Université de Rennes I, UMR CNRS 6118, Campus de Beaulieu, avenue du général Leclerc, 35042 Rennes cedex, France. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT : VULLO , R. & N ÉRAUDEAU , D. 2008. When the “primitive” shark Tribodus (Hybodontiformes) meets the “mod - ern” ray Pseudohypolophus (Rajiformes): the unique co-occurrence of these two durophagous Cretaceous selachians in Charentes (SW France) . Acta Geologica Polonica , 58 (2), 249-255 . Warszawa. The palaeoecology and palaeobiogeography of two Cretaceous selachian genera, Tribodus BRITO & F ERREIRA , 1989 and Pseudohypolophus CAPPETTA & C ASE , 1975 , are briefly discussed. These two similar-sized taxa devel - oped an analogous pavement-like grinding dentition, characterized by massive teeth with a rhomboidal to hexag - onal occlusal surface. Although both genera appear to have been euryhaline forms, the hybodont Tribodus occurred in fresh/brackish water habitats (e.g. deltas) to shallow marine lagoons, whereas the ray Pseudohypolophus lived in brackish water to coastal marine environments. Palaeobiogeographically, their global distribution displays two distinct but adjoined areas, with Tribodus being present in the northern part of Gondwana (Brazil and North Africa), and Pseudohypolophus occurring on both sides of the North Atlantic (North America and Western Europe). How - ever, the two genera coexisted during Cenomanian times within a small overlap zone, localized in western France. -

︎Accepted Manuscript

︎Accepted Manuscript First remains of neoginglymodian actinopterygians from the Jurassic of Monte Nerone area (Umbria-Marche Apennine, Italy) Marco Romano, Angelo Cipriani, Simone Fabbi & Paolo Citton To appear in: Italian Journal of Geosciences Received date: 24 May 2018 Accepted date: 20 July 2018 doi: https://doi.org/10.3301/IJG.2018.28 Please cite this article as: Romano M., Cipriani A., Fabbi S. & Citton P. - First remains of neoginglymodian actinopterygians from the Jurassic of Monte Nerone area (Umbria-Marche Apennine, Italy), Italian Journal of Geosciences, https://doi.org/10.3301/ IJG.2018.28 This PDF is an unedited version of a manuscript that has been peer reviewed and accepted for publication. The manuscript has not yet copyedited or typeset, to allow readers its most rapid access. The present form may be subjected to possible changes that will be made before its final publication. Ital. J. Geosci., Vol. 138 (2019), pp. 00, 7 figs. (https://doi.org/10.3301/IJG.2018.28) © Società Geologica Italiana, Roma 2019 First remains of neoginglymodian actinopterygians from the Jurassic of Monte Nerone area (Umbria-Marche Apennine, Italy) MARCO ROMANO (1, 2, 3), ANGELO CIPRIANI (2, 3), SIMONE FABBI (2, 3, 4) & PAOLO CITTON (2, 3, 5, 6) ABSTRACT UMS). The Mt. Nerone area attracted scholars from all Since the early nineteenth century, the structural high of Mt. over Europe and was studied in detail since the end of Nerone in the Umbria-Marche Sabina Domain (UMS – Central/ the nineteenth century, due to the richness in invertebrate Northern Apennines, Italy) attracted scholars from all over macrofossils, especially cephalopods, and the favorable Europe due to the wealth of fossil fauna preserved in a stunningly exposure of the Mesozoic succession (e.g. -

Ultraviolet Light As a Tool for Investigating Mesozoic Fishes, With

Mesozoic Fishes 5 – Global Diversity and Evolution, G. Arratia, H.-P. Schultze & M. V. H. Wilson (eds.): pp. 549-560, 2 figs. © 2013 by Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil, München, Germany – ISBN 978-3-89937-159-8 Ultraviolet light as a tool for investigating Mesozoic fi shes, with a focus on the ichthyofauna of the Solnhofen archipelago Helmut TISCHLINGER and Gloria ARRATIA Abstract A historical review of the discovery and use of ultraviolet light (UV light) in studies of fossils is provided together with a presentation of UV techniques currently used in fossil invertebrate and tetrapod research. Advantages of the use of UV techniques are presented and discussed in detail, as are certain hazards that may derive from the use of these techniques when strict recommendations are not followed. While UV techniques have proven to be important in revealing sutures, other articulations, hidden bones, and/or the presence of soft tissues in fos- sil tetrapods and invertebrates, they have been scarcely used in fish research. We provide here a few examples documenting the importance of UV techniques in understanding early ontogenetic stages of development, in providing and/or clarifying some morphological characters, and even revealing unexpected new information in fishes (e. g., squamation and formation of vertebral elements in aspidorhynchids; ossification of bones in teleosts). A list of Mesozoic deposits that have given satisfactory results when their fossils have been studied under UV techniques is presented. Introduction “The use of ultraviolet fluorescence in the study and photographing of fossils has scarcely received the at- tention it deserves. By its use, it is said, obscure sutures can be traced, determinations of delicate structures can be made and many other applications are possible.” (CAMP & HANNA 1937: 50). -

Edward Lhwyd

Learning more... Edward Lhwyd Edward Lhwyd those things that they might discover, and the The earliest documented book could easily be taken into the field and used geological specimens to there because of its handy octavo size. survive in the Museum’s As an appendix at the end of the book were six collections are those letters to friends, dealing with geological described by Lhwyd in his subjects. The sixth, addressed to John Ray and Lithophylacii Britannici dated 29 July 1698, extends to twelve pages, and ichnographia of 1699. sets out Lhwyd’s views on the origin of fossils. One hundred and twenty copies were “He suggested a sequence in which mists and published in February of that year; a vapours over the sea were impregnated with the second, posthumous, Editio Altera was ‘seed’ of marine animals. These were raised and published in 1760. A selection of Lhwyd’s carried for considerable distances before they surviving specimens, and the plates of the descended over land in rain and fog. The 1760 edition are figured here. ‘invisible animacula’ then penetrated deep into the earth and there germinated; and in this way Who was Edward Lhwyd? complete replicas of sea organisms, or sometimes Edward Lhwyd was born in 1660, the illegitimate only parts of individuals, were reproduced in son of Edward Lloyd of Llandforda, near stone. Lhwyd also suggests that fossil plants Oswestry, Shropshire, and Bridget Pryse of known to him only as resembling leaves of ferns Gogerddan, Cardiganshire. In 1682 he entered and mosses which have minute ‘seed’, were Jesus College, Oxford, where he studied for five formed in the same manner. -

A New Chondrichthyan Fauna from the Late Jurassic of the Swiss

[Papers in Palaeontology, 2017, pp. 1–41] A NEW CHONDRICHTHYAN FAUNA FROM THE LATE JURASSIC OF THE SWISS JURA (KIMMERIDGIAN) DOMINATED BY HYBODONTS, CHIMAEROIDS AND GUITARFISHES by LEA LEUZINGER1,5 ,GILLESCUNY2, EVGENY POPOV3,4 and JEAN-PAUL BILLON-BRUYAT1 1Section d’archeologie et paleontologie, Office de la culture, Republique et Canton du Jura, Hotel^ des Halles, 2900, Porrentruy, Switzerland 2LGLTPE, UMR CNRS ENS 5276, University Claude Bernard Lyon 1, 2 rue Rapha€el Dubois, F-69622, Villeurbanne Cedex, France 3Department of Historical Geology & Paleontology, Saratov State University, 83 Astrakhanskaya Str., 410012, Saratov, Russia 4Institute of Geology & Petroleum Technology, Kazan Federal University, Kremlevskaya Str. 4/5, 420008, Kazan, Russia 5Current address: Centro Regional de Investigaciones Cientıficas y Transferencia Tecnologica de La Rioja (CRILAR), Provincia de La Rioja, UNLAR, SEGEMAR, UNCa, CONICET, Entre Rıos y Mendoza s/n, (5301) Anillaco, La Rioja, Argentina; [email protected] Typescript received 27 November 2016; accepted in revised form 4 June 2017 Abstract: The fossil record of chondrichthyans (sharks, Jurassic, modern neoselachian sharks had overtaken hybo- rays and chimaeroids) principally consists of isolated teeth, donts in European marine realms, the latter being gradually spines and dermal denticles, their cartilaginous skeleton confined to brackish or freshwater environments. However, being rarely preserved. Several Late Jurassic chondrichthyan while the associated fauna of the Porrentruy platform indi- assemblages have been studied in Europe based on large bulk cates marine conditions, neoselachian sharks are surprisingly samples, mainly in England, France, Germany and Spain. rare. The chondrichthyan assemblage is largely dominated by The first study of this kind in Switzerland is based on con- hybodonts, guitarfishes (rays) and chimaeroids that are all trolled excavations in Kimmeridgian deposits related to the known to be euryhaline. -

Vertebrate Assemblages from the Early Late Cretaceous of Southeastern Morocco: an Overview

Journal of African Earth Sciences 57 (2010) 391–412 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of African Earth Sciences journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jafrearsci Geological Society of Africa Presidential Review No. 16 Vertebrate assemblages from the early Late Cretaceous of southeastern Morocco: An overview L. Cavin a,*, H. Tong b, L. Boudad c, C. Meister a, A. Piuz a, J. Tabouelle d, M. Aarab c, R. Amiot e, E. Buffetaut b, G. Dyke f, S. Hua g, J. Le Loeuff f a Dpt. de Géologie et Paléontologie, Muséum de Genève, CP 6434, 1211 Genève 6, Switzerland b CNRS, UMR 8538, Laboratoire de Géologie de l’Ecole Normale Supérieure, 24 rue Lhomond, 75231 Paris Cedex 05, France c Faculté des Sciences et Techniques, BP, 509, Boutalamine, Errachidia, Morocco d Musée Municipal, 76500 Elbeuf-sur-Seine, France e IVPP, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 142 XiZhiMenWai DaJie, Beijing 100044, China f School of Biology and Environmental Science, University College Dublin, Belfield, Dublin 4, Ireland g Musée des Dinosaures, 11260 Espéraza, France article info abstract Article history: Fossils of vertebrates have been found in great abundance in the continental and marine early Late Cre- Received 16 June 2009 taceous sediments of Southeastern Morocco for more than 50 years. About 80 vertebrate taxa have so far Received in revised form 9 December 2009 been recorded from this region, many of which were recognised and diagnosed for the first time based on Accepted 11 December 2009 specimens recovered from these sediments. In this paper, we use published data together with new field Available online 23 December 2009 data to present an updated overview of Moroccan early Late Cretaceous vertebrate assemblages. -

Chondrichthyan Teeth from the Early Triassic Paris Biota (Bear Lake County, Idaho, USA)

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2019 Chondrichthyan teeth from the Early Triassic Paris Biota (Bear Lake County, Idaho, USA) Romano, Carlo ; Argyriou, Thodoris ; Krumenacker, L J Abstract: A new, diverse and complex Early Triassic assemblage was recently discovered west of the town of Paris, Idaho (Bear Lake County), USA. This assemblage has been coined the Paris Biota. Dated earliest Spathian (i.e., early late Olenekian), the Paris Biota provides further evidence that the biotic recovery from the end-Permian mass extinction was well underway ca. 1.3 million years after the event. This assemblage includes mainly invertebrates, but also vertebrate remains such as ichthyoliths (isolated skeletal remains of fishes). Here we describe first fossils of Chondrichthyes (cartilaginous fishes) from the Paris Biota. The material is composed of isolated teeth (mostly grinding teeth) preserved on two slabs and representing two distinct taxa. Due to incomplete preservation and morphological differences to known taxa, the chondrichthyans from the Paris Biota are provisionally kept in open nomenclature, as Hybodontiformes gen. et sp. indet. A and Hybodontiformes gen. et sp. indet. B, respectively. The present study adds a new occurrence to the chondrichthyan fossil record of the marine Early Triassic western USA Basin, from where other isolated teeth (Omanoselache, other Hybodontiformes) as well as fin spines of Nemacanthus (Neoselachii) and Pyknotylacanthus (Ctenachanthoidea) and denticles have been described previously. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geobios.2019.04.001 Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-170655 Journal Article Accepted Version The following work is licensed under a Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) License. -

Freshwater-Influenced 18Op for the Shark Asteracanthus

Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Biogeosciences Discuss., 12, 12899–12921, 2015 www.biogeosciences-discuss.net/12/12899/2015/ doi:10.5194/bgd-12-12899-2015 BGD © Author(s) 2015. CC Attribution 3.0 License. 12, 12899–12921, 2015 This discussion paper is/has been under review for the journal Biogeosciences (BG). Freshwater- Please refer to the corresponding final paper in BG if available. 18 influenced δ Op for the shark Stable isotope study of a new Asteracanthus chondrichthyan fauna (Kimmeridgian, L. Leuzinger et al. Porrentruy, Swiss Jura): an unusual Title Page freshwater-influenced isotopic Abstract Introduction composition for the hybodont shark Conclusions References Asteracanthus Tables Figures L. Leuzinger1,2,a, L. Kocsis3,4, J.-P. Billon-Bruyat2, S. Spezzaferri1, and J I 3 T. Vennemann J I 1 Département des Géosciences, Université de Fribourg, Chemin du Musée 6, 1700 Fribourg, Back Close Switzerland 2Section d’archéologie et paléontologie, Office de la culture, République et Canton du Jura, Full Screen / Esc Hôtel des Halles, 2900 Porrentruy, Switzerland 3 Faculté des géosciences et de l’environnement, Université de Lausanne, Quartier Printer-friendly Version UNIL-Mouline, Bâtiment Géopolis, 1015 Lausanne, Switzerland 4Universiti Brunei Darussalam, Faculty of Science, Geology Group, Jalan Tungku Link, BE Interactive Discussion 1410, Brunei Darussalam 12899 Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | anow at: CRILAR, 5301 Anillaco, La Rioja, Argentina BGD Received: 12 June 2015 – Accepted: 19 July 2015 – Published: 12 August 2015 Correspondence to: L. Leuzinger ([email protected]) 12, 12899–12921, 2015 Published by Copernicus Publications on behalf of the European Geosciences Union. -

Was There a Mesozoic and Cenozoic Marine Predatory Revolution?

POST-PALEOZOIC PATTERNS IN MARINE PREDATION: WAS THERE A MESOZOIC AND CENOZOIC MARINE PREDATORY REVOLUTION? SALLY E. WALKERI AND CARLTON E. BRETT2 'Department of Geology, University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia 30602 USA 2Department of Geology, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, Ohio 45221-0013 USA ABSTRACT-Mesozoic and Cenozoic evolution ofpredators involved a series ofepisodes. Predators rebounded rather rapidly after the Permo-Triassic extinction and by the Middle Triassic a variety ofnew predator guilds had appeared, including decapod crustaceans with crushing claws, shell-crushing sharks and bonyfish, as well as marine reptiles adaptedfor crushing, smashing, and piercing shells. While several groups (e.g., placodonts, nothosaurs) became extinct in the Late Triassic crises, others (e.g., ichthyosaurs) survived; and the Jurassic to Early Cretaceous saw the rise ofmalacostracan crustaceans with crushing chelae and predatory vertebrates-in particular, the marine crocodilians, ichthyosaurs, and plesiosaurs. The late Cretaceous saw unprecedented levels of diversity ofmarine predaceous vertebrates including pliosaurids, plesiosaurs, and mosasaurs. The great Cretaceous Tertiary extinction decimated marine reptiles. However, most invertebrate andfish predatory groups survived; and during the Paleogene, predatory benthic invertebrates showed a spurt ofevolution with neogastropods and new groupsofdecapods, while the teleostsand neoselachian sharks both undenventparallel rapid evolutionary radiations; these werejoinedby new predatory guilds -

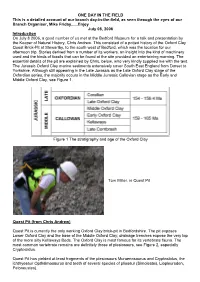

One Day in the Field.Pdf

ONE DAY IN THE FIELD This is a detailed account of our branch day-in-the-field, as seen through the eyes of our Branch Organiser, Mike Friday......Enjoy July 08, 2006 Introduction On July 8 2006, a good number of us met at the Bedford Museum for a talk and presentation by the Keeper of Natural History, Chris Andrew. This consisted of a potted history of the Oxford Clay Quest Brick-Pit at Stewartby, to the south west of Bedford, which was the location for our afternoon trip. Stories derived from a number of its workers, an insight into the kind of machinery used and the kinds of fossils that can be found at the site provided an entertaining morning. The essential details of the pit are explained by Chris, below, who very kindly supplied me with the text. The Jurassic Oxford Clay marine sediments extensively cover South East England from Dorset to Yorkshire. Although still appearing in the Late Jurassic as the Late Oxford Clay stage of the Oxfordian series, the majority occurs in the Middle Jurassic Callovian stage as the Early and Middle Oxford Clay, see Figure 1. Figure 1 The stratigraphy and age of the Oxford Clay Tom Miller, in Quest Pit Quest Pit (from Chris Andrew) Quest Pit is currently the only working Oxford Clay brick-pit in Bedfordshire. The pit exposes Lower Oxford Clay and the base of the Middle Oxford Clay; drainage trenches expose the very top of the more silty Kellaways Beds. The Oxford Clay is most famous for its vertebrate fauna.