MGMT BULLETIN2-V2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A New State Record for Aguascalientes, Mexico: Phrynosoma Cornutum (Squamata: Phrynosomatidae), the Texas Horned Lizard

Herpetology Notes, volume 7: 551-553 (2014) (published online on 3 October 2014) A new state record for Aguascalientes, Mexico: Phrynosoma cornutum (Squamata: Phrynosomatidae), the Texas horned lizard José Carlos Arenas-Monroy1*, Uri Omar García-Vázquez1, Rubén Alonso Carbajal-Márquez2 and Armando Cardona-Arceo3 Horned lizards of the genus Phrynosoma are widely most are typical of the Chihuahuan desert herpetofauna distributed through North America and range from (Morafka, 1977); some of these species have only southern Canada to western Guatemala (Sherbrooke, recently been documented (e.g. Quintero-Díaz et al., 2003). The genus comprises 17 species (Leaché and 2008; Sigala-Rodríguez et al., 2008; Sigala-Rodríguez McGuire, 2006; Nieto-Montes de Oca et al., 2014) and Greene, 2009). However, these arid plains still that exhibit exceptional morphological, ecological, remain relatively unexplored, because the majority and behavioral adaptations to arid environments of sampling efforts have focused on the canyons, (Sherbrooke, 1990, 2003). mountains, and sierras on the western half of the state Of these, Phrynosoma cornutum (Harlan, 1825) (Vázquez-Díaz and Quintero-Díaz, 2005). Here, we inhabits grasslands and scrublands from central United document the first records of Phrynosoma cornutum States southward to the Mexican states of Chihuahua, from the state of Aguascalientes. Coahuila, Durango, Nuevo León, San Luis Potosí, During a field trip on 16 July 2008, UOGV collected a Sonora, Tamaulipas, and Zacatecas from sea level up to male Phrynosoma cornutum ca. 4.7 km S of San Jacinto, 1830 m above sea level (m asl); this species has one of Rincón de Romos (22.304219°N, 102.238156°W; the largest ranges in the genus (Price, 1990). -

Sunshine Is Delicious, Rain Is Refreshing, Wind Braces Us Up, Snow Is Exhilarating; There Is Really No Such Thing As Bad Weather

3/14/11 The Midden Photo by Nathan Veatch Galveston Bay Area Chapter - Texas Master Naturalists April 2011 Table of Contents AT/Stewardship/Ed 2 Spring is Here by Diane Humes, President 2011 Outreach Opportunities Prairie Ponderings 3 Sunshine is delicious, rain is refreshing, wind braces us up, snow is exhilarating; there Wetland Wanderings 4 is really no such thing as bad weather, only different kinds of good weather. - John Ruskin Spring 2011 Class 6 Fishy Facts 7 We have had all kinds of good weather this winter, threat of ice, snow, and sleet unfortunately causing our first-ever chapter meeting cancellation in February. “Heartbreak” Turtles 7 Fortunately, we all stayed warm, dry, and safe. Our speaker, Chris LaChance, has re- Hook ‘em Horns 9 scheduled her presentation for the June meeting, so all is now well. We look forward Horny Toads 10 to all different kinds of good weather and good times for the coming year! FoGISP Training 11 The new chapter training class began February 17 and Raptor Workshop 12 continues most Thursdays into May. Check the schedule and please drop by to meet the 22 future Guppies from Julie 13 Galveston Bay Area Master Naturalists and welcome Red Harvester Ants 14 them to our mission of preservation, restoration, and education about our natural environment. The new class members bring a wealth of experience and love of nature, most citing experiences camping and exploring the outdoors since childhood. They are already into the food, fun, and friendship! The year 2011 marks our chapter’s 10th anniversary and plans are being formulated for a year of celebration. -

N REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: SAURIA: PHRYNOSOMATIDAE PHRYNOSOMA Phrynosoma Modestum Girard

630.1 n REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: SAURIA: PHRYNOSOMATIDAE PHRYNOSOMAMODESTUM Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. Whiting, M.J. and J.R. Dixon. 1996. Phrynosoma modestum. Phrynosoma modestum Girard Roundtail Homed Lizard Phrynosoma modesturn Girard, in Baird and Girard, 1852:69 (see Banta, 1971). Type-locality, "from the valley of the Rio Grande west of San Antonio .....and from between San Antonio and El Paso del Norte." Syntypes, National Mu- seum of Natural History (USNM) 164 (7 specimens), sub- Figure. Adult Phrynosoma modestum from Doha Ana County, adult male, adult male, and 5 adult females, USNM 165660, New Mexico. Photograph by Suzanne L. Collins, courtesy of an adult male, and Museum of Natural History, University The Center for North American Amphibians and Reptiles. of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UIMNH) 40746, an adult male, collected by J.H. lark in May or June 1851 (Axtell, 1988) (not examined by authors). See Remarks. Phrynosomaplatyrhynus: Hemck,Terry, and Hemck, 1899: 136. Doliosaurus modestus: Girard, 1858:409. Phrynosoma modestrum: Morafka, Adest, Reyes, Aguirre L., A(nota). modesta: Cope, 1896:834. and Lieberman, 1992:2 14. Lapsus. Content. No subspecies have been described. and Degenhardt et al. (1996). Habitat photographs appeared in Sherbrooke (1981) and Switak (1979). Definition. Phrynosoma modestum is the smallest horned liz- ard, with a maximum SVL of 66 mm in males and 71 mm in Distribution. Phrynosoma modestum occurs in southern and females (Fitch, 1981). It is the sister taxon to l? platyrhinos, western Texas, southern New Mexico, southeastern Arizona and and is part of the "northern radiation" (sensu Montanucci, 1987). north-central Mexico. -

REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: PHRYNOSOMATIDAE Sceloporus Poinsettii

856.1 REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: PHRYNOSOMATIDAE Sceloporus poinsettii Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. Webb, R.G. 2008. Sceloporus poinsettii. Sceloporus poinsettii Baird and Girard Crevice Spiny Lizard Sceloporus poinsettii Baird and Girard 1852:126. Type-locality, “Rio San Pedro of the Rio Grande del Norte, and the province of Sonora,” restricted to either the southern part of the Big Burro Moun- tains or the vicinity of Santa Rita, Grant County, New Mexico by Webb (1988). Lectotype, National Figure 1. Adult male Sceloporus poinsettii poinsettii (UTEP Museum of Natural History (USNM) 2952 (subse- 8714) from the Magdalena Mountains, Socorro County, quently recataloged as USNM 292580), adult New Mexico (photo by author). male, collected by John H. Clark in company with Col. James D. Graham during his tenure with the U.S.-Mexican Boundary Commission in late Au- gust 1851 (examined by author). See Remarks. Sceloporus poinsetii: Duméril 1858:547. Lapsus. Tropidolepis poinsetti: Dugès 1869:143. Invalid emendation (see Remarks). Sceloporus torquatus Var. C.: Bocourt 1874:173. Sceloporus poinsetti: Yarrow “1882"[1883]:58. Invalid emendation. S.[celoporus] t.[orquatus] poinsettii: Cope 1885:402. Seloporus poinsettiii: Herrick, Terry, and Herrick 1899:123. Lapsus. Sceloporus torquatus poinsetti: Brown 1903:546. Sceloporus poissetti: Král 1969:187. Lapsus. Figure 2. Adult female Sceloporus poinsettii axtelli (UTEP S.[celoporus] poinssetti: Méndez-De la Cruz and Gu- 11510) from Alamo Mountain (Cornudas Mountains), tiérrez-Mayén 1991:2. Lapsus. Otero County, New Mexico (photo by author). Scelophorus poinsettii: Cloud, Mallouf, Mercado-Al- linger, Hoyt, Kenmotsu, Sanchez, and Madrid 1994:119. Lapsus. Sceloporus poinsetti aureolus: Auth, Smith, Brown, and Lintz 2000:72. -

Horned Lizards (Phrynosoma) of Sonora, Mexico: Distribution And

RESEARCH ARTICLE Horned Lizards (Phrynosoma) of Sonora, Mexico: Distribution and Ecology Cecilia Aguilar-Morales, Universidad de Sonora, Departamento de Investigaciones Científicas y Tecnológicas, Blvd. Luis Encinas y Rosales SN, Hermosillo, SON; [email protected] Thomas R. Van Devender, GreaterGood, Inc., 6262 N. Swan Road, Suite 150, Tucson, AZ; [email protected] Mexico is recognized globally as a mega-diversity of the Sierra San Javier, the southernmost Sky Island country. The state of Sonora has very diverse fauna, (Van Devender et al. 2013). The Sierra Madre Oc- flora, and vegetation. The diversity of horned lizards in cidental reaches its northern limit in eastern Sonora, the genus Phrynosoma (Phrynosomatidae) in the state with Madrean species present in the oak woodland and of Sonora is a reflection of the landscape and biotic di- pine-oak forests in the higher elevations of the Sky Is- versity. In this paper, we summarize the distribution lands. West of the Madrean Archipelago, desertscrub and ecology of eight species of Phrynosoma in Sonora. vegetation is present in the Sonoran Desert lowlands of Mexico is western and central Sonora. Methods recognized Phrynosoma records globally as a Study area Eight species of Phrynosoma are reported from So- mega-diversity The great biodiversity of Sonora is the result of nora (Enderson et al. 2010; Rorabaugh and Lemos country. The complex biogeography and ecology. The elevation in 2016). Distribution records from various sources and state of Sonora Sonora ranges from sea level at the Gulf of California many photo vouchers are publicly available in the to over 2600 m in the Sierras Los Ajos and Huachinera Madrean Discovery Expeditions (MDE) database has very diverse (Mario Cirett-G., pers. -

Iguanid and Varanid CAMP 1992.Pdf

CONSERVATION ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR IGUANIDAE AND VARANIDAE WORKING DOCUMENT December 1994 Report from the workshop held 1-3 September 1992 Edited by Rick Hudson, Allison Alberts, Susie Ellis, Onnie Byers Compiled by the Workshop Participants A Collaborative Workshop AZA Lizard Taxon Advisory Group IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group SPECIES SURVIVAL COMMISSION A Publication of the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group 12101 Johnny Cake Ridge Road, Apple Valley, MN 55124 USA A contribution of the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, and the AZA Lizard Taxon Advisory Group. Cover Photo: Provided by Steve Reichling Hudson, R. A. Alberts, S. Ellis, 0. Byers. 1994. Conservation Assessment and Management Plan for lguanidae and Varanidae. IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group: Apple Valley, MN. Additional copies of this publication can be ordered through the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, 12101 Johnny Cake Ridge Road, Apple Valley, MN 55124. Send checks for US $35.00 (for printing and shipping costs) payable to CBSG; checks must be drawn on a US Banlc Funds may be wired to First Bank NA ABA No. 091000022, for credit to CBSG Account No. 1100 1210 1736. The work of the Conservation Breeding Specialist Group is made possible by generous contributions from the following members of the CBSG Institutional Conservation Council Conservators ($10,000 and above) Australasian Species Management Program Gladys Porter Zoo Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum Sponsors ($50-$249) Chicago Zoological -

Texas Horned Lizard Watch Monitoring Packet

Management and Monitoring Packet What’s happened to contents all the horny toads? About Horned Lizards......................2 Everyone loves horny toads, but for many Texans, the fierce-looking, yet Management of amiable, reptiles are only a fond childhood memory. Once common through- out most of the state, horned lizards have disappeared from many parts of Horned Lizards .................................4 their former range. How to Monitor A statewide survey conducted by the Horned Lizard Conservation Society in Horned Lizards .................................7 1992 confirmed many Texans’ personal experiences—in the latter part of the Landowner Access 20th century the Texas Horned Lizard nearly disappeared from the eastern Request Form ...................................8 third of Texas and many respondents reported that horned lizards were in- creasingly rare in Central and North Texas. Only in West and South Texas do Site Survey Data Form .....................9 populations seem somewhat stable. Transect Data Form ...................... 10 Many factors have been proposed as culprits in the disappearance of horned lizards, often fondly called “horny toads,” including collection for the pet Contact Information ..................... 11 trade, spread of the red imported fire ant, changes in agricultural land use, habitat loss and fragmentation as a result of urbanization, and environmental References ..................................... 11 contaminants. For the most part, however, the decline of horned lizards has remained a mystery with little understanding of management actions that could be taken to reverse it. Even less is known about the status of our other two horned lizard species—the Round-tailed Horned Lizard and the Greater Short-horned Lizard. But you can help! Through participation in Texas Horned Lizard Watch as a citizen scientist, you can collect data and observations about the presence or absence of horned lizards and habitat characteristics on your monitoring site. -

Colouration Is Probably Used to Warn Off Predators. Contrasting

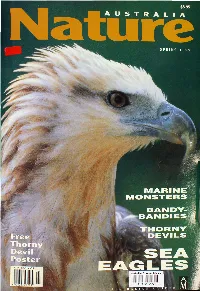

p lJp Front ne misty morning, while camp cl near a . adu ational Park, I was lucky enoug bi11 ab on,,a in Kak . h to . ellied Sea-Eagle catch mg its first meal of the witnes s a White-b . ama IJ1g Sight, as seem1 gly f m OU� day. Jt was an � � . rn of . swooped !own, th1 ust its nowhere a massive bird : talons 111�0 a large silver fish. In the the water and pulled out same fluid to a nearby perch and proceeded to 1110tion it then flew . tear its catch apart. After weeks of seemg t h ese b'1r d s perched sile ntly along the rivers of the far orthern Territory, it wa thrilling to finally see one hunting. Penny Olsen ha studied so A shower of airborne droplets trail a White-bellied Sea-Eagle as it these magnificent birds for over 15 year don't miss her struggles to gain height, a fish firmly grasped in both feet. article "Winged Pirates" as it provides a view into the world of tlie White-bellied Sea-Eagle-and includes her own fir t-hand full of vicious pointed teeth. Related to modern-day snakes, experience of the power of those massive talons. these reptiles propelled themselve through the water by From Sea-Eagles to sea monster , we go to Western powerful front and rear paddles, and used their teeth to crack Australia and join John Long as he describes the excitement open the hard-coiled shells of ammonites. John also describes of discovering Australia's largest and most complete keleton the other types of marine reptiles that dominated our seas at of a 1110 asaur-a ten-metre-long marine reptile with a head the time of the dinosaurs. -

Download Publication

Caesar Kleberg A Publication of the Caesar Kleberg Wildlife ResearchTracks Institute CAESAR KLEBERG WILDLIFE RESEARCH INSTITUTE TEXAS A&M UNIVERSITY - KINGSVILLE 1 Caesar Kleberg Volume 5 | Issue 2 | Fall 2020 In This Issue 3 From the Director Tracks 4 Restoration: Just What Do You Mean By That? 8 The Unique Nature of Colonial-nesting Waterbirds 12 Texas Horned Lizard 8 Detectives Learn More About CKWRI The Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute at 16 Donor Spotlight: Texas A&M University-Kingsville is a Master’s and Mike Reynolds Ph.D. Program and is the leading wildlife research organization in Texas and one of the finest in the nation. Established in 1981 by a grant from the Caesar Kleberg 20 Fawn Survival and Foundation for Wildlife Conservation, its mission is Recruitment in South Texas to provide science-based information for enhancing the conservation and management of Texas wildlife. 23 Alumni Spotlight: J. Dale James Visit our Website www.ckwri.tamuk.edu Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute Texas A&M University-Kingsville 700 University Blvd., MSC 218 Kingsville, Texas 78363 4 (361) 593-3922 Follow us! Facebook: @CKWRI Twitter: @CKWRI Instagram: ckwri_official Cover Photo by iStock 2 Magazine Design and Layout by Gina Cavazos Caesar Kleberg From the Director The overarching mission of the Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute is to promote wildlife conservation. We do this primarily by conducting research and producing knowledge to benefit wildlife managers and land stewards. We also promote wildlife conservation by training the next generation of wildlife biologists Tracks through our graduate education programs. However, producing knowledge and trained professionals is not enough. -

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History Database

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History database Abdala, C. S., A. S. Quinteros, and R. E. Espinoza. 2008. Two new species of Liolaemus (Iguania: Liolaemidae) from the puna of northwestern Argentina. Herpetologica 64:458-471. Abdala, C. S., D. Baldo, R. A. Juárez, and R. E. Espinoza. 2016. The first parthenogenetic pleurodont Iguanian: a new all-female Liolaemus (Squamata: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. Copeia 104:487-497. Abdala, C. S., J. C. Acosta, M. R. Cabrera, H. J. Villaviciencio, and J. Marinero. 2009. A new Andean Liolaemus of the L. montanus series (Squamata: Iguania: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. South American Journal of Herpetology 4:91-102. Abdala, C. S., J. L. Acosta, J. C. Acosta, B. B. Alvarez, F. Arias, L. J. Avila, . S. M. Zalba. 2012. Categorización del estado de conservación de las lagartijas y anfisbenas de la República Argentina. Cuadernos de Herpetologia 26 (Suppl. 1):215-248. Abell, A. J. 1999. Male-female spacing patterns in the lizard, Sceloporus virgatus. Amphibia-Reptilia 20:185-194. Abts, M. L. 1987. Environment and variation in life history traits of the Chuckwalla, Sauromalus obesus. Ecological Monographs 57:215-232. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2003. Anfibios y reptiles del Uruguay. Montevideo, Uruguay: Facultad de Ciencias. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2007. Anfibio y reptiles del Uruguay, 3rd edn. Montevideo, Uruguay: Serie Fauna 1. Ackermann, T. 2006. Schreibers Glatkopfleguan Leiocephalus schreibersii. Munich, Germany: Natur und Tier. Ackley, J. W., P. J. Muelleman, R. E. Carter, R. W. Henderson, and R. Powell. 2009. A rapid assessment of herpetofaunal diversity in variously altered habitats on Dominica. -

The Effects of Burning and Grazing on Survival, Home Range, and Prey Dynamics of the Texas Horned Lizard in a Thornscrub Ecosystem

The Effects of Burning and Grazing on Survival, Home Range, and Prey Dynamics of the Texas Horned Lizard in a Thornscrub Ecosystem Anna L. Burrow1, Richard T. Kazmaier1, Eric C. Hellgren1, and Donald C. Ruthven, III2 Abstract.—We examined the effects of rotational can increase the amount of woody vegetation (Archer livestock grazing and prescribed winter burning on the and Smeins 1991). Ruthven et al. (2000) found that state threatened Texas horned lizard, Phrynosoma forbs increased on southern Texas rangelands in the first cornutum, by comparing home range sizes, survival year after a winter burn, but were not affected by estimates and prey abundance across burning and grazing. Bunting and Wright (1977) also found that grazing treatments in southern Texas. Adult lizards were forbs and grass cover increased following fire. Ants, the fitted with backpacks carrying radio transmitters and main prey of horned lizards, are not deleteriously relocated daily. Prey abundance (harvester ants, affected by fire or grazing (McCoy and Kaiser 1990; Pogonomyrmex rugosus) and activity were greater in Heske and Campbell 1991; McClaran and Van Devender burned pastures, but grazing had a variable effect 1995:165 Fox et al. 1996). depending on the timing since the last burn. Home ranges in burned pastures were smaller than in Specific objectives of our research were to: compare the unburned pastures in the active season. Level of grazing relative abundance and activity of harvester ants, (heavy vs. moderate) did not affect home range size. Pogonomyrmex rugosus, the main food source of the Texas Summer survival rates of horned lizards were higher in horned lizard, among different burning and grazing the moderately grazed sites than the heavily grazed sites. -

Phrynosoma Cornutum and P

STRATEGIES OF PREDATORS AND THEIR PREY: OPTIMAL FORAGING AND HOME RANGE BEHAVIOR OF HORNED LIZARDS (PHRYNOSOMA SPP.) AND RESPONSE BY HARVESTER ANTS (POGONOMYRMEX DESERTORUM). Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors MUNGER, JAMES CAMERON. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 10/10/2021 20:56:51 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/185315 INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame.