The Thai Cave Boys' Rescue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SPRING 2022 Supercharge Your Brain James, Ph.D

PEGASUS BOOKS SPRING 2022 Supercharge Your Brain James, Ph.D. Goodwin BOOK DESCRIPTION The definitive guide to keeping your brain healthy for a long and lucid life, by one of the world's leading scientists in the field of brain health and ageing. The brain is our most vital and complex organ. It controls and coordinates our actions, thoughts and interactions with the world around us. It is the source of personality, of our sense of self, and it shapes every aspect of our human experience. Yet most of us know precious little about how our brains actually work, or what we can do to optimise their performance. Whilst cognitive decline is the biggest long-term health worry for many of us, practical knowledge of how to look after our brain is thin on the ground. In this ground-breaking new book, leading expert Professor James Goodwin explains how simple strategies concerning exercise, diet, social life, and sleep can transform your brain health paradigm, and shows how you can keep your brain youthful and stay sharp across your life. Combining the latest scientific research with insightful storytelling and practical advice, HARDCOVER Supercharge Your Brain reveals everything you need to know about how your brain functions, and what you can do to keep it in On Sale: 01/04/22 peak condition. Pegasus Books 9781643138671 AUTHOR BIO Science First Print: 15,000 Professor James Goodwin PhD is a director of the Brain Health 6 x 9, 384 pages Network (www.brain.health) and a special advisor to the Global Carton quantity: 12 Council on Brain Health. -

Where Is the Great Barrier Reef? Pdf, Epub, Ebook

WHERE IS THE GREAT BARRIER REEF? PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Nico Medina | 112 pages | 01 Nov 2016 | Penguin Putnam Inc | 9780448486994 | English | New York, United States Where is the Great Barrier Reef? PDF Book Physiographic Diagram of Australia. Demand valve oxygen therapy First aid Hyperbaric medicine Hyperbaric treatment schedules In-water recompression Oxygen therapy Therapeutic recompression. Britannica Quiz. Seabirds will land on the platforms and defecate which will eventually be washed into the sea. Diving mask Snorkel Swimfin. The types of corals that reproduced also changed, leading to a "long-term reorganisation of the reef ecosystem if the trend continues. In July , a new zoning plan took effect for the entire Marine Park, and has been widely acclaimed as a new global benchmark for marine ecosystem conservation. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Lying off the Queensland coast, that great system of coral reefs and atolls owes its origin to a combination of continental drift into warmer waters , rifting, sea-level change, and subsidence. It is important to know how far out from land the reef is located as well. Retrieved 3 September Diving support equipment. Four traditional owners groups agreed to cease the hunting of dugongs in the area in due to their declining numbers, partially accelerated by seagrass damage from Cyclone Yasi. Flat reefs known as planar reefs are found in the northern and southern parts, near Cape York Peninsula, Princess Charlotte Bay and Cairns. Archived from the original on 16 October Region" PDF. Bibcode : LimOc.. Archived from the original on 7 May Above the surface, the plant life of the cays is very restricted, consisting of only some 30 to 40 species. -

Vol. 9 No. 4, October - December 2018

VOL. 9 NO. 4, OCTOBER - DECEMBER 2018 ว�ศวกรรมปฐพ� ทีมกรุป ขยายขอบเขตงาน กับการปองกันภัยพ�บัติในประเทศไทย สูธุรกิจเกี่ยวเนื่อง A Path to Sustainable Growth Geotechnical Engineering and Disaster Prevention in Thailand 8 รศ.ดร.สุทธิศักดิ์ ศรลัมพ ภาคว�ชาว�ศวกรรมโยธา คณะว�ศวกรรมศาสตร มหาว�ทยาลัยเกษตรศาสตร Assoc. Prof. Dr. Suttisak Soralump เปดศักราชอินโด-แปซ�ฟ�ก : Civil Engineering Department 12 ทิศทางอาเซ�ยน Faculty of Engineering Indo-Pacific Era: Kasetsart University ASEAN Future Direction 16 2 ทักทาย | A Word from Our Chairman เวลากับการเปลี่ยนแปลงเป็นของคู่กัน สารบัญ Time Brings Changes Contents ทักทาย l A Word from Our Chairman 2 สวัสดีครับ We are approaching the last quarter of ทีมของเรา l Our TEAM 3 ผมขอกล่าวทักทาย สำาหรับ TEAM GROUP the year. The TEAM GROUP Newsletter in Newsletter ฉบับนี้ ซึ่งเป็นฉบับไตรมาสสุดท้าย your hand is the last issue of this year. เปิดมุมมอง l Different Facets 8 ของปีนี้แล้ว We all know that time is important. But do we value time appropriately? Make time คุยนอกกรอบกับทีม l Talk with TEAM 12 เวลาเป็นสิ่งสำาคัญ ผมอยากให้ทุกคน to review what you have done so far, what A S E A N T i p s 1 6 ให้ความสำาคัญ และเริ่มทบทวนกับสิ่งที่ได้ทำามา plans you haven’t activated, and what dreams และยังไม่ได้ทำา หรือทำาไม่ได้ตามฝัน แผนการ are still unrealized. Whatever the target is, บอกเล่าเก้าสิบ l What’s Going On? 18 หรือแผนงานที่ได้วาด ได้ตั้งเป้าหมายเอาไว้ let’s start working on it. Time and tide wait Expert Talk 20 ต้องเร่งลงมือทำาแล้ว เพราะเวลาไม่เคยคอยใคร for no one. ที่ผ่านมา ทีมกรุ๊ปมีแผนและดำาเนินการ At TEAM GROUP, -

The Divers Logbook Free

FREE THE DIVERS LOGBOOK PDF Dean McConnachie,Christine Marks | 240 pages | 18 May 2006 | Boston Mills Press | 9781550464788 | English | Ontario, Canada Printable Driver Log Book Template - 5+ Best Documents Free Download A dive log is a record of the diving history of an underwater diver. The log may either be in a book, The Divers Logbook hosted softwareor web based. The log serves purposes both related to safety and personal records. Information in a log may contain the date, time and location, the profile of the diveequipment used, air usage, above and below water conditions, including temperature, current, wind and waves, general comments, and verification by the buddyinstructor or supervisor. In case of a diving accident, it The Divers Logbook provide valuable data regarding diver's previous experience, as well as the other factors that might have led to the accident itself. Recreational divers are generally advised to keep a logbook as a record, while professional divers may be legally obliged to maintain a logbook which is up to date and complete in its records. The professional diver's logbook is a legal document and may be important for getting employment. The required content and formatting of the professional diver's logbook is generally specified by the registration authority, but may also be specified by an industry association such as the International Marine Contractors Association IMCA. A more minimalistic log book for recreational divers The Divers Logbook are only interested in keeping a record of their accumulated experience total number of dives and total amount of time underwatercould just contain the first point of the above list and the maximum depth of the dive. -

Ireland's Thai Cave Rescue Hero Rewarded

PARAMEDICSTHAI CAVE RESUCE ON TV IRELAND'S THAI CAVE RESCUE HERO REWARDED Irish caver Jim Warny played a vital part in this summer’s heroic rescue of the Thai junior soccer team and their coach. His contribution to the rescue mission is particularly amazing since caving is purely a hobby for this Lufthansa electrician, and he tells Lorraine Courtney about having no hesitation in diving in at the deep end at a moment’s notice! im Warny was presented with a ‘Just in Time’ Rescue Award at the Irish Water Safety’s recent conference in Athlone, in recognition of his extraordinary contribution as Ja rescue diver to the Tham Luang cave rescue effort in Thailand this summer, when 12 boys (aged 11 to 17) and their 25-year-old assistant coach were rescued in this unprecedented operation exercised to military precision. On 23 June, the football team was trapped in a flash flood inside Tham Luang, just four kilometres from the cave’s entrance. After days of pumping water from the cave system and a respite from rain, the rescue teams quickly worked on getting everyone out before the next monsoon rain, which was predicted to start around 11 July. With some of the most highly-skilled cave rescuers in the world, the rescue became an international operation, including military personnel from Thailand, America, Australia, Britain and China. In total, the effort involved more than 10,000 people, including over 100 divers, many rescue workers, representatives from up to 100 governmental agencies, 900 police officers and 2,000 soldiers. The operation required ten police helicopters, seven police ambulances, more than 700 diving cylinders, and the pumping of more than a billion litres of water out of the caves. -

Egypt Forces Kill 40 Militants in Crackdown After Bus Attack Three Vietnamese Tourists, Egyptian Guide Killed • Amir Condemns Deadly Bombing

RABI ALTHANI 23, 1440 AH SUNDAY, DECEMBER 30, 2018 28 Pages Max 17º Min 08º 150 Fils Established 1961 ISSUE NO: 17720 The First Daily in the Arabian Gulf www.kuwaittimes.net Kuwait 49th among 109 states in Syria army deploys to Manbij Oz, revered writer and Israeli Ronaldo double seals new 56attracting investments: Dhaman in new alliance with Kurds 19 voice for peace, dies aged 79 27 record for voracious Juve Egypt forces kill 40 militants in crackdown after bus attack Three Vietnamese tourists, Egyptian guide killed • Amir condemns deadly bombing GIZA, Egypt: Egyptian police killed 40 suspects in a to a restaurant for dinner” when the bomb exploded. crackdown yesterday after a roadside bomb hit a tour Company officials were heading to Cairo yesterday bus claiming the lives of three Vietnamese holidaymak- and plans were made to allow some relatives of the vic- ers and an Egyptian guide. Thirty alleged “terrorists” tims to also fly to Egypt. One of them was Nguyen were killed in separate raids in Giza governorate, home Nguyen Vu whose sister Nguyen Thuy Quynh, 56, died to Egypt’s famed pyramids and the scene of Friday’s in the bombing, while her husband, Le Duc Minh, was deadly bombing, while 10 others were killed in the wounded. The couple, both aged 56, were in the restive North Sinai, the interior ministry said without seafood business, Quynh’s younger brother said. “We directly linking them to the attack. were all very shocked... My sister and her husband It said authorities had received information the sus- travel quite a lot and they are quite experienced in trav- pects were preparing a spate of attacks “targeting state elling abroad,” Vu told AFP. -

2019 Program of Events

PLANETSCIENCEWEEK.NET.AU ENVIRONMENTbeer INTERACTIVEchocolate QUIZ DANCE AntarcticaCOMEDY ADVENTURE NEUTRON storiesCURIOUS CLIMATE wildlife TECHart LEGO NATIONAL SCIENCE WEEK TASMANIA EVENTS | AUGUST 2019 WELCOME TO NATIONAL 2 SCIENCE WEEK TASMANIA 3 FROM OUR PATRON The Tasmanian National Science Week Coordinating Committee acknowledges the Traditional Custodians Nobel Laureate, Professor Emerita Elizabeth Blackburn of lutruwita, Tasmania and respects the palawa/pakana people for their living cultures and knowledge systems. We pay our respects to Elders past and present and thank all community members who are Welcome to the National Science Week Tasmania Science is our greatest asset for facing the world’s assisting in the delivery of this state-wide program in 2019. program of events. In here you will find a pathway most significant challenges. While I continue to work into the heart of Tasmanian science, a place where in a field of research dedicated to improving human you will be inspired and amazed and develop a new health, more and more I try to champion science and appreciation for the outstanding work that scientists, technology as tools that can deal with other global researchers and innovators are doing right here in issues such as planetary health. EVENTS NEAR YOU our beautiful island home. Science is for everyone. It is not separate from KEY TO EVENTS: I am a very proud Tasmanian. I was born in Snug us and is part of all our lives. Science Week is a SOUTHERN EVENTS ...............................................4–14 Children's University Film and grew up in Launceston, and it was here that fabulous opportunity for each of us to participate YOUNG TASSIE SCIENTISTS ..........................................15 I was first inspired to pursue a career in science. -

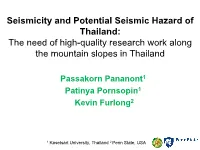

Landslide Hazard of Thailand

Seismicity and Potential Seismic Hazard of Thailand: The need of high-quality research work along the mountain slopes in Thailand Passakorn Pananont1 Patinya Pornsopin1 Kevin Furlong2 1 Kasetsart University, Thailand 2 Penn State, USA Thailand Tectonic Setting (Morley et al., 2001) EQs (M>5) Seismicity of Thailand Major Historical and Recent Earthquakes That Affects Thailand 24 March 2011 M6.7 in Myanmar (100-150 Deaths in Myanmar) M6.2 Chiang Rai EQ (May 5th, 2014, 18:08 pm, 19.66°N 99.67°E 10km) More than 15,000 building with degrees from minor damages to total collapse and yielded a total damage of US$300 million Damages Map vs Simulated PGA (M6.2 at 10km depth, Sadigh et al., 1997’s attenuation model) Aftershocks Monitoring and Relocation Delineation of two ‘conjugate’ fault trends A rare earthquake (ML 4.3) occurred at 09:44:25 hrs.(UTC) on 16 April 2012 in the Si Sunthon District, Thalang District, Phuket EQ Phuket province, southern Thailand This earthquake caused slight building damages and was felt throughout the Phuket island. MMI 6 near the epicenter 29 aftershocks M>1.5ML occurred during 24hrs from the mainshock. Seismic Hazard in the Southern Thailand Length Magnitude Segment Slip (m) (km) (Mw) 1 13.87 6.55 1.22 2 31.31 6.86 1.56 4 32.93 6.88 1.59 5 18.98 6.67 1.34 Full Khlong 172.93 7.51 2.63 Marui Full Ranong 430.00 7.85 3.48 Short Khlong 47.234 7.02 1.77 Marui Short 96.82 7.29 2.21 Ranong Offshore fault segments and the potential maximum (After Ramirez 2019) earthquake magnitude (Wesnousky, 2008) Scenario Shake Map: intensity up to VIII PGA and intensity maps from scenario earthquakes on faults 1, 2 3 and 4. -

7/10/2019 1 Overview Tham Luang Cave

7/10/2019 “OPERATION WILD BOAR” The Tham Luang Cave Rescue In Thailand Presented by Derek Anderson OVERVIEW . Tham Luang Cave . Chronology . “3-Day Rescue” . Lessons Learned . Questions THAM LUANG CAVE . Located in Chang Rai province, Northern Thailand on the border with Burma/Myanmar. 4th Largest cave in Thailand. Approx. 8 Km long . It’s a “Dry” cave 6 months a year. After Monsoon rains arrive in June/July, it becomes flooded the remainder of the year. Extremely dangerous once high rain flows enter ”restrictions” in the cave and flood the sumps. 1 7/10/2019 -DIFFICULT TERRAIN -STEEP MUDDY HILLS 600 meters Entrance 2 7/10/2019 TIMELINE/CHRONOLOGY SATURDAY, 23 JUNE 2018 . The Wild Boar Soccer team and their coach decided to go hike Tham Luang cave after soccer practice. (They HAD Insert done this before a few times together, kind of a “right of passage” for newer Cave/Bike Pic members) . Family members begin to worry once nightfall arrives and none of the boys arrive home or are heard from. Their bicycles and some back packs are found chained at the mouth of the Cave that night. THE SEARCH BEGINS…... SUNDAY, 24 JUNE 2018 . Local Search and Rescue crews from Mai Sai and civilian volunteers are responding to the cave. Local Thai Government request Thai Military assistance . An EX-PAT named VERNON UNSWORTH who has been exploring/mapping Tham Luang the last 5 years is contacted by some local villagers who request his assistance. He attempts to make his way back into the depths of the cave to locate the boys. -

A Case Study of Tham Luang Nang Non Cave

RMUTSB Acad. J. 7(2 ) : 247 -258 (2019 ) 247 Geophysics under stressed: a case study of Tham Luang Nang Non Cave Chanarop Vichalai 1* Abstract In the middle of June, 2018, the members of Wild Boar Academy football team consisted of 12 boys and their coach were trapped in a flooded cave complex of Tham Luang Nang Non, Mae Sai District, Chiang Rai Province, Thailand. The plight of the boys and their coach had drawn international attention, with divers, engineers and medics among others flying in from around the world to assist the rescue mission. Initially, there were three maps provided by different sources but none of them were accurate. Therefore, an application of geophysical exploration technique was considered as the alternative method for the determination accurate cave route and geological structure that allowed water flowing through the cave. In addition, electrical resistivity imaging survey and seismic survey were also applied. The results of the resistivity survey indicated that the geological structure of the mountain was useful for drilling operation at D01 and D88. The resistivity survey results at North and South of the mountain indicated the possibility of underground water that flew to the cave. Moreover, the seismic technique used for the earthquake measurement was applied to determine accurate cave route and the position of seismic source along the cave route. The seismic source for this test was from the cooperation with the Royal Thai Navy diving team by hitting their own empty air tank on the ground floor. Unfortunately, the application of the seismic technique was not a success due to the interference of high ambient noise from electrical water pumps, groundwater drilling, and the rescue activities. -

KCT Summer Schedule for 2019

E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.kilkeecivictrust.org Follow Us On Facebook Kilkee Civic Trust - Summer Schedule for 2019 Kilkee Civic Trust, (KCT), is a non-profit organisation working to enhance the quality of life in Kilkee, and its hinterland, by preserving and promoting its cultural heritage, and so making it a more attractive place to live, work and invest. Talks - Arts in Focus - Music Table of contents: Talks: Page No.’s 2 to 11 Arts in Focus: Page No. 12 Music: Page No.’s 13 to 16 KCT Heritage Projects: Page No. 17 All of our events are recorded by Raidió Corca Baiscinn for subsequent broadcast on 92.5 & 94.8 fm streaming & later podcast on www.rcb.ie Photograph courtesy of - © www.westclare.net 1 KCT Talks 2019 - All Talks will be hosted at Cultúrlann Sweeney, O’Connell St., Kilkee. Entry to all KCT Talks is Free of Charge. All of our speakers give of their time and energy on a pro-bono basis. The appreciation of the audience & KCT is expressed by way of presenting each speaker with a Book Token, or similar, at the end of each Talk. A Donations Box is provided at all Talks to assist us in defraying necessary expenses. Date: Wednesday, 3th July 2019 at 8pm No. 1 of 9 Talks Speaker: Ruairí McKiernan Talk Title: Hope and Healing in a Troubled World Talk Description: We live in an increasingly busy world where we're presented with huge opportunities, but also massive challenges. Issues such as anxiety, depression, loneliness, and social isolation are on the rise. -

September 2018

tech talk GettingThe inside storythe Boys Out Tham Luang Cave Rescue Text by Rosemary E. Lunn Edited by Peter Symes On Saturday, 23 June 2018, a football team of boys in Thailand, aged 11 to 16, finished practice under the watchful eye of their 25-year-old coach, Ekkapol Chantawong. The group then cycled to and entered a popular tourist attraction, Tham Luang Cave. Some of the boys had never visited it before and were curious to know what it looked like. They explored the cave for about an hour before turning around and retraced their steps. They could not get out. At around 9:00 p.m., Sungwut ??????? Kummongkol, leader of the Mae Sai Rescue Unit Team, received a call that some of the children had disappeared. It prompted a search to begin. 81 X-RAY MAG : 87 : 2018 EDITORIAL FEATURES TRAVEL NEWS WRECKS EQUIPMENT BOOKS SCIENCE & ECOLOGY TECH EDUCATION PROFILES PHOTO & VIDEO PORTFOLIO US AIR FORCE / PETER SYMES The Thai Navy SEALs were brave but not equipped, nor trained tech talk for a nil-visibility overhead envi- ronment in which you cannot go up if you have a problem, and they found the caving and cave diving challenging. At 10:00 p.m., Kummongkol led on Monday, 25 June, and head- “A diver felt his way through with the first responders into the cave. ed for Chamber 3 in the cave. It his hands in the dark. He found a The team of 14 local rescue work- took them about an hour to get hole that he could push through ers set up a light and found the to the chamber.