St Kilda Botanical Gardens | Future Directions Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australian Plants Society Waverley

AAustralianustralian PPlantslants SSocietyociety WWaverleyaverley November 2020 Australian Plants Society (Waverley) Inc. Reg. No. A0013116G Arthropodium https://sites.google.com/view/apswaverley PO Box 248 Glen Waverley Vic 3150 strictum Meetings Third Thursday of month, Ground floor, Wadham House, 52 Wadham Parade, Mt Waverley (Melways Map 61 E12) Commencing 8pm APS Waverley Group Events Other Events DECEM BER Thursday 3 rd commencing 6:00pm MARCH 24 th - 28 th 2021 End-of-year Breakup Dinner And Twilight Stroll 25th Melbourne International Flower & Garden Show Venue: Wattle Park Royal Exhibition Building and Carlton Gardens, Drive into the park from Riversdale Road. Proceed to the car Melbourne. park at the end of the entrance road. Meet at the BBQ closest to the car park at 6:00pm. Bring your own food and drink APRIL 17 th 2021 Wear shoes suitable for a short stroll through the park on bush APS Geelong Australian Native Plant Sale, tracks. ‘Wirrawilla’, Lovely Banks. APRIL 25 th 2021 10 am – 4 pm Monthly meetings in Wadham House cancelled until APS Yarra Yarra Autumn Plant Sale, permitted by government regulations Eltham Senior Citizens Hall, Eltham. MAY 1 st 2021 10 am - 3.30 pm APS Mornington Peninsula Plant Sale, Seawinds Gardens, Arthurs Seat Park, Purves Road, Arthurs Seat. JUNE 26 th & 27 th 2021 10 am – 4 pm APS Ballarat Winter Flower Show. Flower show, plant sales etc. Robert Clark Centre, Ballarat Botanic Gardens, Gilles Street, Ballarat. ALL EVENTS HELD ONLY IF PERMITTED BY HEALTH REGULATIONS. PLEASE CONFIRM WITH EVENT ORGANISER THAT EVENT DETAILS HAVE NOT CHANGED. STORIES & PHOTOS OF NATIVE PLANTS ARE URGENTLY NEEDED; CAN YOU HELP? Please email them to [email protected] WILLIAM ROBERT GUILFOYLE – Gifted garden designer William Guilfoyle was born in 1840 at Chelsea, England and migrated to Sydney as a child with the Guilfoyle family in 1849. -

Melbourne Parks and Gardens Through the Magic Lantern

While the depression of the 1890s has dented their confidence, Melbournians have good reason to feel pleased with themselves as the new century begins: Queen Victoria has graciously agreed to the formation of the new Commonwealth; the first motor cars are appearing on the city’s streets (a mixed blessing, admittedly); some of the better homes are lit by electricity, the marvel of the age, and the telephone is revolutionising business communications (although, of course, nobody would think of having one in the home). Furthermore, a new city-wide sewerage system has drastically reduced the risk of typhoid and other deadly diseases. Australians, as one contemporary journalist enthuses, ‘... are equipped by a more than usually high average of education, a broader measure of political privilege, and a more generous share of individual freedom and public liberty than those who have preceded us in the race.’ 1 There can be few more potent expressions of civic pride than the public park or garden. From the mid-nineteenth century, almost every Victorian town of consequence had established its own municipal botanic garden, an achievement unmatched by any other state. And now, with working hours reduced to an average of 48 per week, citizens of all social classes had the leisure to enjoy them. And enjoy them they did! That horticultural genius, William Guilfoyle, was transforming Melbourne’s Botanic Gardens into a verdant paradise, while the ring of public parks around the city – Carlton, Alexandra, Fitzroy, Treasury and Flagstaff Gardens, and the Domain - which only thirty years earlier the visiting English writer, Anthony Trollope, had derided as ‘not lovely’ and ‘not in themselves well kept’2 had been rejuvenated, with wide, tree-lined avenues, colourful parterres and mixed borders. -

NSW Rainforest Trees Part

This document has been scanned from hard-copy archives for research and study purposes. Please note not all information may be current. We have tried, in preparing this copy, to make the content accessible to the widest possible audience but in some cases we recognise that the automatic text recognition maybe inadequate and we apologise in advance for any inconvenience this may cause. · RESEARCH NOTE No. 35 ~.I~=1 FORESTRY COMMISSION OF N.S.W. RESEARCH NOTE No. 35 P)JBLISHED 197R N.S.W. RAINFOREST TREES PART VII FAMILIES: PROTEACEAE SANTALACEAE NYCTAGINACEAE GYROSTEMONACEAE ANNONACEAE EUPOMATIACEAE MONIMIACEAE AUTHOR A.G.FLOYD (Research Note No. 35) National Library of Australia card number and ISBN ISBN 0 7240 13997 ISSN 0085-3984 INTRODUCTION This is the seventh in a series ofresearch notes describing the rainforest trees of N.S. W. Previous publications are:- Research Note No. 3 (I 960)-N.S.W. Rainforest Trees. Part I Family LAURACEAE. A. G. Floyd and H. C. Hayes. Research Note No. 7 (1961)-N.S.W. Rainforest Trees. Part II Families Capparidaceae, Escalloniaceae, Pittosporaceae, Cunoniaceae, Davidsoniaceae. A. G. Floyd and H. C. Hayes. Research Note No. 28 (I 973)-N.S.W. Rainforest Trees. Part III Family Myrtaceae. A. G. Floyd. Research Note No. 29 (I 976)-N.S.W. Rainforest Trees. Part IV Family Rutaceae. A. G. Floyd. Research Note No. 32 (I977)-N.S.W. Rainforest Trees. Part V Families Sapindaceae, Akaniaceae. A. G. Floyd. Research Note No. 34 (1977)-N.S.W. Rainforest Trees. Part VI Families Podocarpaceae, Araucariaceae, Cupressaceae, Fagaceae, Ulmaceae, Moraceae, Urticaceae. -

Australian Notable Gardens? Towards a List for Each State, Territory and Region…

Australian Notable Gardens? Towards a list for each state, territory and region… The AGHS are keen to find out from you which ten gardens in your region, state or territory – public and private – you think are remarkable or notable in that area. This might be for their heritage significance, their quality, or their intactness or ‘integrity’ (e.g. of an era, or style). It might be for their historic, expression of their geographic location, their style or design or their ‘intact’ character. They may be heritage-listed, in recognition of this – or unsung gems. Below are some ideas of ours as a start, with some reasons why. In two lists: ‘Public’ and ‘Private’. They are listed in chronological order – i.e. oldest garden to youngest. This in no way makes judgements about any being ‘better’ than any others – just ‘remarkable’ in that state or area. By ‘Public’ we mean publicly owned, and open to the public. So parks, botanic gardens and the like. NB: this does not imply ‘free’ entry, necessarily. With increasing budget stringency, some ‘Public’ gardens now charge fees for entry, to help cover maintenance costs. An example are the suite of properties, some with well renowned historic gardens, run by Sydney Living Museums, e.g. Elizabeth Farm, Parramatta, NSW and Vaucluse House garden, Vaucluse, NSW. Universities are ‘private’ entities, and ‘private’ means privately-owned, some of which are opened to the public (usually for a fee). Again, the emphasis is not on whether entry is free or paid – it is on ownership and accessibility. AGHS membership often means that members can access privately- owned gardens that do not, normally, or frequently, open to the general public. -

Pests, Diseases, and Aridity Have Shaped the Genome of Corymbia Citriodora

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Recent Work Title Pests, diseases, and aridity have shaped the genome of Corymbia citriodora. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5t51515k Journal Communications biology, 4(1) ISSN 2399-3642 Authors Healey, Adam L Shepherd, Mervyn King, Graham J et al. Publication Date 2021-05-10 DOI 10.1038/s42003-021-02009-0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-021-02009-0 OPEN Pests, diseases, and aridity have shaped the genome of Corymbia citriodora ✉ Adam L. Healey 1,2 , Mervyn Shepherd 3, Graham J. King 3, Jakob B. Butler 4, Jules S. Freeman 4,5,6, David J. Lee 7, Brad M. Potts4,5, Orzenil B. Silva-Junior8, Abdul Baten 3,9, Jerry Jenkins 1, Shengqiang Shu 10, John T. Lovell 1, Avinash Sreedasyam1, Jane Grimwood 1, Agnelo Furtado2, Dario Grattapaglia8,11, Kerrie W. Barry10, Hope Hundley10, Blake A. Simmons 2,12, Jeremy Schmutz 1,10, René E. Vaillancourt4,5 & Robert J. Henry 2 Corymbia citriodora is a member of the predominantly Southern Hemisphere Myrtaceae family, which includes the eucalypts (Eucalyptus, Corymbia and Angophora; ~800 species). 1234567890():,; Corymbia is grown for timber, pulp and paper, and essential oils in Australia, South Africa, Asia, and Brazil, maintaining a high-growth rate under marginal conditions due to drought, poor-quality soil, and biotic stresses. To dissect the genetic basis of these desirable traits, we sequenced and assembled the 408 Mb genome of Corymbia citriodora, anchored into eleven chromosomes. Comparative analysis with Eucalyptus grandis reveals high synteny, although the two diverged approximately 60 million years ago and have different genome sizes (408 vs 641 Mb), with few large intra-chromosomal rearrangements. -

Street Tree Master Plan Report © Sunshine Coast Regional Council 2009-Current

Sunshine Coast Street Tree Master Plan 2018 Part A: Street Tree Master Plan Report © Sunshine Coast Regional Council 2009-current. Sunshine Coast Council™ is a registered trademark of Sunshine Coast Regional Council. www.sunshinecoast.qld.gov.au [email protected] T 07 5475 7272 F 07 5475 7277 Locked Bag 72 Sunshine Coast Mail Centre Qld 4560 Acknowledgements Council wishes to thank all contributors and stakeholders involved in the development of this document. Disclaimer Information contained in this document is based on available information at the time of writing. All figures and diagrams are indicative only and should be referred to as such. While the Sunshine Coast Regional Council has exercised reasonable care in preparing this document it does not warrant or represent that it is accurate or complete. Council or its officers accept no responsibility for any loss occasioned to any person acting or refraining from acting in reliance upon any material contained in this document. Foreword Here on our healthy, smart, creative Sunshine Coast we are blessed with a wonderful environment. It is central to our way of life and a major reason why our 320,000 residents choose to live here – and why we are joined by millions of visitors each year. Although our region is experiencing significant population growth, we are dedicated to not only keeping but enhancing the outstanding characteristics that make this such a special place in the world. Our trees are the lungs of the Sunshine Coast and I am delighted that council has endorsed this master plan to increase the number of street trees across our region to balance our built environment. -

Eucalypt Discovery Walk

Eucalypt Discovery Walk This self-guided walk through the Botanic Gardens features 21 eucalypts, each of which has an interpretive sign. Additional information is provided here. A round trip, starting with #1 Eucalyptus cunninghamii in the North Car Park and returning past #21 Eucalyptus viminalis to the Visitor Information Centre, will take about an hour and covers a range of terrain (e.g. stairs, lawn, uneven surfaces). There are about 850 eucalypt species, almost all occurring naturally only in Australia. Indeed, eucalypts are a defining feature of the Australian landscape. They are an important component of Australian vegetation and provide a habitat for many native animals. Some species have a wide geographic distribution, others are extremely restricted in their natural habitat and may need conservation. There is great diversity of size, form, leaf and bark type among eucalypts. Eucalypts have many commercial uses. An important source of wood products in Australia, they are also the world’s most widely-planted hardwoods. Large areas are being grown in Brazil, South Africa, India, China and elsewhere mainly for pulp and paper production. Species featured in this walk have been selected to illustrate the diversity and many uses of eucalypts. Acknowledgements This walk has been supported by the Bjarne K. Dahl Trust (www.dahltrust.org.au) a philanthropic fund. Dahl was a Norwegian forester who developed a great affinity with the Australian Bush and left his entire estate to establish a fund which focuses solely on eucalypts. Funds have also been provided by the Public Fund of the Friends of the Australian National Botanic Gardens (www.friendsanbg.org.au). -

Growth and Nutrition of Corymbia Citriodora Seedlings Using Doses of Liquid Swine Waste

DOI: 10.14295/CS.v8i2.1851 Comunicata Scientiae 8(2): 256-264, 2017 Article e-ISSN: 2177-5133 www.comunicatascientiae.com Growth and nutrition of Corymbia citriodora seedlings using doses of liquid swine waste João Antônio da Silva Coelho¹, Cristiane Ramos Vieira², Oscarlina Lúcia dos Santos Weber1 1 Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso, Cuiabá, MT, Brazil. 2. Universidade de Cuiabá, Cuiabá, MT, Brazil. *Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract The experiment was installed in a greenhouse with the aimed to verify the influence of liquid swine waste in the development and nutrition of Corymbia citriodora seedlings. The swine waste was mixed with a commercial substrate in order to analyze the effects of five doses, in a randomized block design, considering the N requirement of the species, which were T1 – 0%; T2 – 50%; T3 – 100%; T4 – 150% and; T5 – 200% and one treatment with mineral fertilization for comparison. The Corymbia citriodora seeds were germinated in plastic tubes with a commercial substrate plus swine waste. As the seedlings reached about five centimeters the thinning was performed, and when the plants reached 15 cm in length the growth analysis was started. At the end of the experiment the seedlings were measured, weighed and milled for macro and micronutrients determination. The best doses of liquid swine waste were 150% and 200% which showed the highest growth average values of the Corymbia citriodora seedlings, to the detriment of the nutritional and physical improvement of the substrate. Keywords: Corymbia, organic waste, forestry nutrition Introduction and heavy metals; or water quality because the Swine breeding in Brazil has increased in swine waste can contaminate groundwater. -

La Trobeana Is Kindly Sponsored by Mr Peter Lovell Lovell Chen Architects & Heritage Consultants

LAA TTROBEANAROBEANA Journal of the C. J. La Trobe Society Inc. Journal ofVol.11, the No.C. J. 3, LaNovember Trobe 2012Society Inc. ISSN 1447-4026 Vol. 6, No. 2, June 2007 ISSN 1447-4026 La Trobeana is kindly sponsored by Mr Peter Lovell LOVEll CHEN ARCHITECTS & HERITAGE CONSULTANTS Lovell Chen Pty Ltd, Level 5, 176 Wellington Pde, East Melbourne 3002, Australia Tel: +61 (0)3 9667 0800 Fax: +61 (0)3 9416 1818 Email [email protected] ABN 20 005 803 494 Contents 4 Introduction 37 Jane Wilson A Word from the President Research Report: Charles La Trobe’s contribution to the establishment of the 5 Adrienne E. Clarke Horticultural Gardens at Burnley A Message from the Chancellor of La Trobe University 39 Susan Priestley Crises of 1852 for Lieutenant-Governor Tributes La Trobe, Captain William Dugdale and La Trobeana Henrietta Augusta Davies Journal of the C J La Trobe Society Inc. Dr Brian La Trobe Vol. 11, No 3, November 2012. 6 Tim Gatehouse 46 Dr Jean McCaughey The Turkish La Trobe: The career of ISSN 1447-4026 7 Claude Alexandre de Bonneval, the Editorial Committee 8 Mr Bruce Nixon Sultan’s advisor at the Ottoman Court Loreen Chambers (Hon Editor) Helen Armstrong Articles 54 Roz Greenwood Dianne Reilly Book Review: The French Closet by Robyn Riddett 9 R.W. Home Alison Anderson Burgess La Trobe’s ‘honest looking German’: Designed by Ferdinand Mueller and the botanical Reports and Notices Michael Owen [email protected] exploration of gold-rush Victoria Helen Botham For contributions and subscriptions enquiries contact: 56 Anna Murphy Anniversary of the Death of The Honorary Secretary: Dr Dianne Reilly AM 17 The C. -

WRA Species Report

Family: Sterculiaceae Taxon: Brachychiton populneus Synonym: Poecilodermis populnea Schott & Endl. (basio Common Name: bottletree Sterculia diversifolia G. Don bottelboom kurrajong whiteflower kurrajong Questionaire : current 20090513 Assessor: Chuck Chimera Designation: EVALUATE Status: Assessor Approved Data Entry Person: Chuck Chimera WRA Score 6 101 Is the species highly domesticated? y=-3, n=0 n 102 Has the species become naturalized where grown? y=1, n=-1 103 Does the species have weedy races? y=1, n=-1 201 Species suited to tropical or subtropical climate(s) - If island is primarily wet habitat, then (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2- High substitute "wet tropical" for "tropical or subtropical" high) (See Appendix 2) 202 Quality of climate match data (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2- High high) (See Appendix 2) 203 Broad climate suitability (environmental versatility) y=1, n=0 n 204 Native or naturalized in regions with tropical or subtropical climates y=1, n=0 y 205 Does the species have a history of repeated introductions outside its natural range? y=-2, ?=-1, n=0 y 301 Naturalized beyond native range y = 1*multiplier (see y Appendix 2), n= question 205 302 Garden/amenity/disturbance weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see y Appendix 2) 303 Agricultural/forestry/horticultural weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see n Appendix 2) 304 Environmental weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see n Appendix 2) 305 Congeneric weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) 401 Produces spines, thorns or burrs y=1, n=0 n 402 Allelopathic y=1, n=0 n 403 Parasitic y=1, n=0 n 404 Unpalatable -

Species List Alphabetically by Common Names

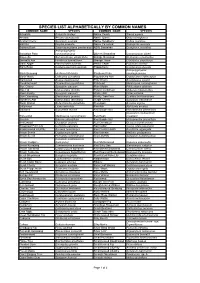

SPECIES LIST ALPHABETICALLY BY COMMON NAMES COMMON NAME SPECIES COMMON NAME SPECIES Actephila Actephila lindleyi Native Peach Trema aspera Ancana Ancana stenopetala Native Quince Guioa semiglauca Austral Cherry Syzygium australe Native Raspberry Rubus rosifolius Ball Nut Floydia praealta Native Tamarind Diploglottis australis Banana Bush Tabernaemontana pandacaqui NSW Sassafras Doryphora sassafras Archontophoenix Bangalow Palm cunninghamiana Oliver's Sassafras Cinnamomum oliveri Bauerella Sarcomelicope simplicifolia Orange Boxwood Denhamia celastroides Bennetts Ash Flindersia bennettiana Orange Thorn Citriobatus pauciflorus Black Apple Planchonella australis Pencil Cedar Polyscias murrayi Black Bean Castanospermum australe Pepperberry Cryptocarya obovata Archontophoenix Black Booyong Heritiera trifoliolata Picabeen Palm cunninghamiana Black Wattle Callicoma serratifolia Pigeonberry Ash Cryptocarya erythroxylon Blackwood Acacia melanoxylon Pink Cherry Austrobuxus swainii Bleeding Heart Omalanthus populifolius Pinkheart Medicosma cunninghamii Blue Cherry Syzygium oleosum Plum Myrtle Pilidiostigma glabrum Blue Fig Elaeocarpus grandis Poison Corkwood Duboisia myoporoides Blue Lillypilly Syzygium oleosum Prickly Ash Orites excelsa Blue Quandong Elaeocarpus grandis Prickly Tree Fern Cyathea leichhardtiana Blueberry Ash Elaeocarpus reticulatus Purple Cherry Syzygium crebrinerve Blush Walnut Beilschmiedia obtusifolia Red Apple Acmena ingens Bollywood Litsea reticulata Red Ash Alphitonia excelsa Bolwarra Eupomatia laurina Red Bauple Nut Hicksbeachia -

Epacris Study Group

ASSOCIATION OF SOCIETIES FOR GROWING AUSTRALIAN PLANTS Inc. EPACRIS STUDY GROUP Group Leader: Gwen Elliot, P.O. Box 655 Heathmont Vic. 3135 NEWSLETTER No. XS (ISSN 103 8-6017) Qctaber zaQ4 Greetings as once again we begin to enjoy the longer days of spring-summer and the encouragement this provides for many of our flowering plants. Despite the generally dry conditions many Epacris species are putting on outstanding floral displays. How are you going with your recording of the flowering times of Epacris impressa in your garden, as well as in nearby bushland or in other areas as you travel within Australia? It really is quite an exciting project because together we, as Study Group members, can make a real contribution to the overall understanding of this species, adding to the knowledge and research of botanists who look in detail at the features of the plant under the microscope and in its natural habitat. It iis a species which occurs both atsea-level and at higher altitudes. How are the flowering times affected when highland plants are cultivated at lower altitudes? Are flowering times different when plants fiom New South Wales for example are gvown much further south in soulhern Victoria or Tasmania ? Epacris impressu seems like an excellent species for us to research in this way. If our project is successful we may perhaps be able to continue with looking at the flowering times of other Epacris which are relatively common in cultivation. In case you have misplaced the recording sheet from our October 2003 Newsletter, another is included in this issue.