2018-Spectators-Igi.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Video Game Archive: Nintendo 64

Video Game Archive: Nintendo 64 An Interactive Qualifying Project submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science by James R. McAleese Janelle Knight Edward Matava Matthew Hurlbut-Coke Date: 22nd March 2021 Report Submitted to: Professor Dean O’Donnell Worcester Polytechnic Institute This report represents work of one or more WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on its web site without editorial or peer review. Abstract This project was an attempt to expand and document the Gordon Library’s Video Game Archive more specifically, the Nintendo 64 (N64) collection. We made the N64 and related accessories and games more accessible to the WPI community and created an exhibition on The History of 3D Games and Twitch Plays Paper Mario, featuring the N64. 2 Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………………… 2 Table of Contents…………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Table of Figures……………………………………………………………………………………………5 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………………….. 7 Executive Summary………………………………………………………………………………………. 8 1-Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………….. 9 2-Background………………………………………………………………………………………… . 11 2.1 - A Brief of History of Nintendo Co., Ltd. Prior to the Release of the N64 in 1996:……………. 11 2.2 - The Console and its Competitors:………………………………………………………………. 16 Development of the Console……………………………………………………………………...16 -

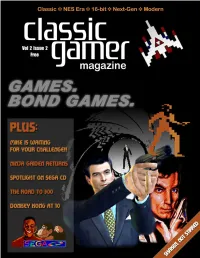

Cgm V2n2.Pdf

Volume 2, Issue 2 July 2004 Table of Contents 8 24 Reset 4 Communist Letters From Space 5 News Roundup 7 Below the Radar 8 The Road to 300 9 Homebrew Reviews 11 13 MAMEusements: Penguin Kun Wars 12 26 Just for QIX: Double Dragon 13 Professor NES 15 Classic Sports Report 16 Classic Advertisement: Agent USA 18 Classic Advertisement: Metal Gear 19 Welcome to the Next Level 20 Donkey Kong Game Boy: Ten Years Later 21 Bitsmack 21 Classic Import: Pulseman 22 21 34 Music Reviews: Sonic Boom & Smashing Live 23 On the Road to Pinball Pete’s 24 Feature: Games. Bond Games. 26 Spy Games 32 Classic Advertisement: Mafat Conspiracy 35 Ninja Gaiden for Xbox Review 36 Two Screens Are Better Than One? 38 Wario Ware, Inc. for GameCube Review 39 23 43 Karaoke Revolution for PS2 Review 41 Age of Mythology for PC Review 43 “An Inside Joke” 44 Deep Thaw: “Moortified” 46 46 Volume 2, Issue 2 July 2004 Editor-in-Chief Chris Cavanaugh [email protected] Managing Editors Scott Marriott [email protected] here were two times a year a kid could always tures a firsthand account of a meeting held at look forward to: Christmas and the last day of an arcade in Ann Arbor, Michigan and the Skyler Miller school. If you played video games, these days writer's initial apprehension of attending. [email protected] T held special significance since you could usu- Also in this issue you may notice our arti- ally count on getting new games for Christmas, cles take a slight shift to the right in the gaming Writers and Contributors while the last day of school meant three uninter- timeline. -

Index | Table of Contents

Intro: Infinity (175) Before you read this book (3) Jet Force Gemini (176) Copyright, Fair Use & Good Faith (4) Knights (177) Forewords (5) Mythri (178) Unseen Covers 1 (12) Resident Evil (179) The History of Unseen64 (13) Saffire (180) Anonymous sources and research (21) Tyrannosaurus Tex (181) Gaming Philology (23) SNES, MegaDrive (Genesis) Games You Will Never Play (183) Preservation of Cancelled Games (25) Akira (185) Frequently Asked Questions (27) Albert Odyssey Gaiden (186) Games you will (never?) play (29) Christopher Columbus (187) Unseen Covers 2 (32) Dream: Land of Giants (187) Interviews: Felicia (190) Adam McCarthy (33) Fireteam Rogue (190) Art Min (36) Interplanetary Lizards (192) Brian Mitsoda (39) Iron Hammer (193) Centre for Computing History (43) Kid Kirby (194) Computer Spiele Museum (46) Matrix Runner (194) Felix Kupis (49) Mission Impossible (195) Frederic Villain (51) Rayman (196) Gabe Cinquepalmi (54) River Raid (198) Grant Gosler (57) Satellite Man (198) Jesse Sosa (61) Socks the Cat Rocks the Hill (199) John Andersen (64) Spinny and Spike (202) Ken Capelli (69) Starfox 2 (202) NOVAK (75) Super quick (205) MoRE Museum (84) X-Women (207) National Videogame Museum (87) Sega 32X / Mega CD Games You Will Never Play (209) Tim Williams (90) Castlevania: The Bloodletting (210) Omar Cornut (93) Hammer vs. Evil D. in Soulfire (210) Terry Greer (97) Shadow of Atlantis (215) William (Bill) Anderson (101) Sonic Mars (216) Scott Rogers (106) Virtua Hamster (218) PC Games You Will Never Play (111) Philips CDI Games You Will Never -

Exploring the Game Master- Player Relationship in Video Games Abel Neto

MESTRADO MULTIMÉDIA - ESPECIALIZAÇÃO EM TECNOLOGIAS Exploring the Game Master- Player relationship in video games Abel Neto M 2016 FACULDADES PARTICIPANTES: FACULDADE DE ENGENHARIA FACULDADE DE BELAS ARTES FACULDADE DE CIÊNCIAS FACULDADE DE ECONOMIA FACULDADE DE LETRAS Exploring the Game Master-Player relationship in video games Abel Neto Mestrado em Multimédia da Universidade do Porto Orientador: Miguel Carvalhais (Professor Auxiliar) Coorientador: Pedro Cardoso (Assistente convidado) Junho de 2016 Resumo O objectivo deste estudo é explorar a relação entre os participantes de jogo que assumem o papel de Game Master e os que assumem o de jogador nos videojogos. Esta relação, escassamente explorada em jogos de computador, existe há décadas em jogos de tabuleiro, um dos primeiros exemplos sendo o Dungeons & Dragons, no qual um participante assume o papel de árbitro e contador de histórias, controlando todos os aspectos do jogo excepto as acções dos jogadores. Através do desenvolvimento de um protótipo de jogo, descobrimos que existe valor na inclusão desta assimetria em jogos de computador, e avaliamos a sua viabilidade e vantagens/desvantagens. PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Videojogos, Game Master, Gameplay, Assimétrico Abstract The purpose of this research is to explore the relationship between game participants that assume the role of Game Master and those that have that of Player in videogames. This relationship, barely explored in computer games, has existed in board games for decades, one of the first examples being Dungeons & Dragons, in which a game participant acts both as a referee and as a storyteller, controlling all aspects of the game, except for the actions of the players. Through the development of a game prototype, we found that there’s value in including this asymmetry in computer games, and evaluated its viability and benefits/disadvantages. -

You've Seen the Movie, Now Play The

“YOU’VE SEEN THE MOVIE, NOW PLAY THE VIDEO GAME”: RECODING THE CINEMATIC IN DIGITAL MEDIA AND VIRTUAL CULTURE Stefan Hall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2011 Committee: Ronald Shields, Advisor Margaret M. Yacobucci Graduate Faculty Representative Donald Callen Lisa Alexander © 2011 Stefan Hall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Ronald Shields, Advisor Although seen as an emergent area of study, the history of video games shows that the medium has had a longevity that speaks to its status as a major cultural force, not only within American society but also globally. Much of video game production has been influenced by cinema, and perhaps nowhere is this seen more directly than in the topic of games based on movies. Functioning as franchise expansion, spaces for play, and story development, film-to-game translations have been a significant component of video game titles since the early days of the medium. As the technological possibilities of hardware development continued in both the film and video game industries, issues of media convergence and divergence between film and video games have grown in importance. This dissertation looks at the ways that this connection was established and has changed by looking at the relationship between film and video games in terms of economics, aesthetics, and narrative. Beginning in the 1970s, or roughly at the time of the second generation of home gaming consoles, and continuing to the release of the most recent consoles in 2005, it traces major areas of intersection between films and video games by identifying key titles and companies to consider both how and why the prevalence of video games has happened and continues to grow in power. -

Starcraft: Brood War Manual (English)

Copyright © 1998 Blizzard Entertainment. All rights reserved. The use of this software product is subject to the terms of the enclosed End User License Agreement. You must accept the End User License Agreement before you can use this product. The Campaign Editor contained in this product is provided strictly for your personal use. The use of the Campaign Editor is subject to additional license restrictions contained inside the product and may not be commercially exploited. Blizzard Hint Line costs .85¢ per minute. Minimum charge .85¢. Average cost per call $2.50. Available to US residents only. Charges commence after a short pause. To avoid charges, hang up immediately. Children under 18 should get their parent’s permission before calling. StarCraft, Diablo, Brood War, and Battle.net, are trademarks and Blizzard Entertainment, and Warcraft are trademarks or registered trademarks of Davidson and Associates, Inc in the U.S. and/or other countries. All other trademarks and trade names are the properties of their respective owners. Uses Smacker Video Technology, Copyright © 1994-1998 by Invisible Inc. d.b.a. by RAD Software Blizzard Entertainment P.O. Box 18979 Irvine, CA 92623 (800) 953-SNOW Direct Sales (949) 955-0283 International Direct Sales (949) 955-0157 Technical Support Fax (949) 955-1382 Technical Support (900) 370-SNOW Blizzard Hint Line http://www.blizzard.com World Wide Web -Table Of Contents- Getting started······································································4 Technical Support································································6 -

Bits N' Bricks S02E25 – Myth, Maori, and a Brain Tumor

Myth, Maori, and a Brain Tumor: The BIONICLE® Saga For a time, LEGO® BIONICLE was a transmedia giant, standing knee-deep in an ocean of successful properties: 70 books, 50 comics and graphic novels, four films, a television show, a trading card game, and countless LEGO toys. And threaded throughout the massive success of the theme sets were the video games – seven released, one lost to a sudden shift of fate. To understand what happened to LEGO BIONICLE: The Legend of Mata Nui and why it was killed – despite being developed in parallel with released prequel, marketed in cereal boxes and comic books nationwide, and nearly complete – you have to understand BIONICLE. As creation myths go, the LEGO toy has a doozy. The LEGO theme set smash hit was inspired by a desire to one up Star Wars’™ epic saga, out gotta-catch-‘em- all the compelling play of Pokémon, and one man’s personal struggle to come to grips with a benign brain tumor. In many ways, BIONICLE was born in fertile creative ground created by myriad factors, including the state of the world and the LEGO Group in the late ‘90s and early 2000s. In 1998, the LEGO Group suffered its first loss, eventually laying off 1,000 employees. And then the following year, the company introduced sets based on licensed properties including Star Wars™. The success of licensed properties underscored the value of backstory for the company, so it started exploring the idea of creating its own properties, working with, among others, renowned Copenhagen advertising agency Advance and its art director Christian Faber. -

Steampunkopedia

For M. & K. "Steampunkopedia Analogue Collection MMIII-MMX" PDF edition, July 2010 compiled by Krzysztof Janicz (Piechur) originally published on Retrostacja/Steampunkopedia 2003-2010 www.steampunk.republika.pl Cover: "Great Steampunk Debate 2010" mash-up by Piechur, idea by Waterbug Suggested format for printing: A5 booklet About Steampunkopedia STEAMPUNKOPEDIA: GUIDE TO A COOL 19th CENTURY Steampunkopedia (est. December 2006) was an international section of Polish steampunk website Retrostacja , combining three major projects: • Steampunk Chronology - a list of nearly 3,000 works set in the chronological order (online since August 2003), • Steampunk Links - a database of over 1,000 links in 12 categories (online since August 2005), • Steampunk TV - a collection of more than 200 music videos, short films, trailers and contemporary silent films (online since November 2006). Steampunk Chronology, the core element of Steampunkopedia, was probably the first attempt to reconstruct a history and an evolution of the genre. My goal was to assemble everything that came within contemporary definition of steampunk (or within many coexisting definitions - see p.72): from modern sf, fantasy & horror set in the 19th century and retrofuturistic alternate history, to mad crossovers, pastiches and mash-ups. Being a work in permanent progress, the list has quickly multipled its initial number of 500 titles, reaching a critical mass after 100 bi-weekly update reports in July 2007. At that time Dieselpunk came into prominence, which gave a chance to split the Chronology into two separate files (see p.57). After another 100 reports (weekly, due to the peaking popularity of the genre – see p.56) the project was cancelled and removed in May 2010.