Reforming Responses to the Challenges of Judicial Incapacity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

High Court of Australia

HIGH COURT OF AUSTRALIA ANNUAL REPORT 2000-01 High Court of Australia Canberra ACT 7 December 2001 Dear Attorney, In accordance with Section 47 of the High Court of Australia Act 1979, I submit on behalf of the Court and with its approval a report relating to the administration of the affairs of the High Court of Australia under Section 17 of the Act for the year ended 30 June 2001, together with financial statements in respect of the year in the form approved by the Minister for Finance. Sub-section 47(3) of the Act requires you to cause a copy of this report to be laid before each House of Parliament within 15 sitting days of that House after its receipt by you. Yours sincerely, (C.M. DOOGAN) Chief Executive and Principal Registrar of the High Court of Australia The Honourable D. Williams, AM, QC, MP Attorney-General Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 CONTENTS Page PART I - PREAMBLE Aids to Access 4 PART II - INTRODUCTION Chief Justice Gleeson 5 Justice Gaudron 5 Justice McHugh 6 Justice Gummow 6 Justice Kirby 6 Justice Hayne 7 Justice Callinan 7 PART III - THE YEAR IN REVIEW Changes in Proceedings 8 Self Represented Litigants 8 The Court and the Public 8 Developments in Information Technology 8 Links and Visits 8 PART IV - BACKGROUND INFORMATION Establishment 9 Functions and Powers 9 Sittings of the Court 9 Seat of the Court 11 Appointment of Justices of the High Court 12 Composition of the Court 12 Former Chief Justices and Justices of the Court 13 PART V - ADMINISTRATION General 14 External Scrutiny 14 Ecologically Sustainable Development -

5281 Bar News Winter 07.Indd

Mediation and the Bar Some perspectives on US litigation Theories of constitutional interpretation: a taxonomy CONTENTS 2 Editor’s note 3 President’s column 5 Opinion The central role of the jury 7 Recent developments 12 Address 2007 Sir Maurice Byers Lecture 34 Features: Mediation and the Bar Effective representation at mediation Should the New South Wales Bar remain agnostic to mediation? Constructive mediation A mediation miscellany 66 Readers 01/2007 82 Obituaries Nicholas Gye 44 Practice 67 Muse Daniel Edmund Horton QC Observations on a fused profession: the Herbert Smith Advocacy Unit A paler shade of white Russell Francis Wilkins Some perspectives on US litigation Max Beerbohm’s Dulcedo Judiciorum 88 Bullfry Anything to disclose? 72 Personalia 90 Books 56 Legal history The Hon Justice Kenneth Handley AO Interpreting Statutes Supreme Court judges of the 1940s The Hon Justice John Bryson Principles of Federal Criminal Law State Constitutional Landmarks 62 Bar Art 77 Appointments The Hon Justice Ian Harrison 94 Bar sports 63 Great Bar Boat Race The Hon Justice Elizabeth Fullerton NSW v Queensland Bar Recent District Court appointments The Hon Justice David Hammerschlag 64 Bench and Bar Dinner 96 Coombs on Cuisine barTHE JOURNAL OF THEnews NSW BAR ASSOCIATION | WINTER 2007 Bar News Editorial Committee Design and production Contributions are welcome and Andrew Bell SC (editor) Weavers Design Group should be addressed to the editor, Keith Chapple SC www.weavers.com.au Andrew Bell SC Eleventh Floor Gregory Nell SC Advertising John Mancy Wentworth Selborne Chambers To advertise in Bar News visit Arthur Moses 180 Phillip Street, www.weavers.com.au/barnews Chris O’Donnell Sydney 2000. -

Situating Women Judges on the High Court of Australia: Not Just Men in Skirts?

Situating Women Judges on the High Court of Australia: Not Just Men in Skirts? Kcasey McLoughlin BA (Hons) LLB (Hons) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, the University of Newcastle January 2016 Statement of Originality This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. I give consent to the final version of my thesis being made available worldwide when deposited in the University's Digital Repository, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Kcasey McLoughlin ii Acknowledgments I am most grateful to my principal supervisor, Jim Jose, for his unswerving patience, willingness to share his expertise and for the care and respect he has shown for my ideas. His belief in challenging disciplinary boundaries, and seemingly limitless generosity in mentoring others to do so has sustained me and this thesis. I am honoured to have been in receipt of his friendship, and owe him an enormous debt of gratitude for his unstinting support, assistance and encouragement. I am also grateful to my co-supervisor, Katherine Lindsay, for generously sharing her expertise in Constitutional Law and for fostering my interest in the High Court of Australia and the judges who sit on it. Her enthusiasm, very helpful advice and intellectual guidance were instrumental motivators in completing the thesis. The Faculty of Business and Law at the University of Newcastle has provided a supportive, collaborative and intellectual space to share and debate my research. -

The High Court and the Parliament Partners in Law-Making Or Hostile Combatants?*

The High Court and the Parliament Partners in law-making or hostile combatants?* Michael Coper The question of when a human life begins poses definitional and philosophical puzzles that are as familiar as they are unanswerable. It might surprise you to know that the question of when the High Court of Australia came into existence raises some similar puzzles,1 though they are by contrast generally unfamiliar and not quite so difficult to answer. Interestingly, the High Court tangled with this issue in its very first case, a case called Hannah v Dalgarno,2 argued—by Wise3 on one side and Sly4 on the other—on 6 and 10 November 1903, and decided the next day on a date that now positively reverberates with constitutional significance, 11 November.5 * This paper was presented as a lecture in the Department of the Senate Occasional Lecture Series at Parliament House on 19 September 2003. I am indebted to my colleagues Fiona Wheeler and John Seymour for their comments on an earlier draft. 1 See Tony Blackshield and Francesca Dominello, ‘Constitutional basis of Court’ in Tony Blackshield, Michael Coper and George Williams (eds), The Oxford Companion to the High Court of Australia, South Melbourne, Vic., Oxford University Press, 2001 (hereafter ‘The Oxford Companion’): 136. 2 (1903) 1 CLR 1; Francesca Dominello, ‘Hannah v Dalgarno’ in The Oxford Companion: 316. 3 Bernhard Ringrose Wise (1858–1916) was the Attorney-General for NSW and had been a framer of the Australian Constitution. 4 Richard Sly (1849–1929) was one of three lawyer brothers (including George, a founder of the firm of Sly and Russell), who all had doctorates in law. -

1974–79), the Elder Son of Albert Sydney Jacobs and Sarah Grace

J Jacobs, Kenneth Sydney (b 5 October 1917; Justice schhafen. He was then appointed as an intelligence officer. 1974–79), the elder son of Albert Sydney Jacobs and Sarah He later said that, after a rather sheltered early life, his army Grace Aggs, was born on Sydney’s north shore at Gordon, years had enabled him to learn much more about human then rural bushland. His childhood centred on his local behaviour, and that this, and the added years, had aided his preparatory school, St John’s Anglican church and the cub success at the Bar. and scout troops, meeting at the church hall. He was edu- Resuming his law studies in 1945, Jacobs graduated LLB in cated at Knox Grammar School and from 1935 at the Uni- 1947, with first-class honours and the University Medal. In versity of Sydney, residing at St Andrew’s College. In 1938, his last year at law school, he was associate to Justice Leslie after graduating BA with honours in Latin and Greek, he Herron, later Chief Justice of NSW. Admitted to the Bar in commenced his LLB and was articled to Duncan Barron. February 1947 as a pupil of Kenneth Asprey, he quickly World War II interrupted his studies. Enlisting in the Aus- developed a general practice, particularly in commercial law, tralian Imperial Forces in May 1940, he served with the 9th taxation law,and equity,and later in constitutional law.He Division in Egypt at the battle of El Alamein in 1942 and in was junior counsel in the High Court in Marcus Clark v New Guinea in 1943; he was at the landings at Lae and Fin- Commonwealth (1952), and junior to Barwick before the Privy Council in Johnson v Commissioner of Stamp Duties (1956). -

The Distinctive Foundations of Australian Democracy

Papers on Parliament No. 42 December 2004 The Distinctive Foundations of Australian Democracy Lectures in the Senate Occasional Lecture Series 2003–2004 Published and printed by the Department of the Senate, Parliament House, Canberra ISSN 1031-976X Published by the Department of the Senate, 2004 Papers on Parliament is edited and managed by the Research Section, Department of the Senate. Edited by Kay Walsh All inquiries should be made to: Assistant Director of Research Procedure Office Department of the Senate Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Telephone: (02) 6277 3164 ISSN 1031–976X ii Contents Alfred Deakin. A Centenary Tribute Stuart Macintyre 1 The High Court and the Parliament: Partners in Law-making, or Hostile Combatants? Michael Coper 13 Constitutional Schizophrenia Then and Now A.J. Brown 33 Eureka and the Prerogative of the People John Molony 59 John Quick: a True Founding Father of Federation Sir Ninian Stephen 71 Rules, Regulations and Red Tape: Parliamentary Scrutiny and Delegated Legislation Dennis Pearce 81 ‘The Australias are One’: John West Guiding Colonial Australia to Nationhood Patricia Fitzgerald Ratcliff 97 The Distinctiveness of Australian Democracy John Hirst 113 The Usual Suspects? ‘Civil Society’ and Senate Committees Anthony Marinac 129 Contents of previous issues of Papers on Parliament 141 List of Senate Briefs 149 To order copies of Papers on Parliament 150 iii Contributors Stuart Macintyre is Ernest Scott Professor of History and Dean of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Melbourne Michael Coper is Dean of Law and Robert Garran Professor of Law at the Australian National University. Dr A.J. -

Hit and Myth in the Law Courts

Dinner Address Hit and Myth in the Law Courts S E K Hulme, AM, QC Copyright 1994 by The Samuel Griffith Society. All rights reserved. Not unexpectedly, in this company, I will talk tonight about only one court; the one on your left as you cross the bridge over the lake. I want to do two things. I want firstly to consider a belief and a practice and a proposal concerning the High Court, in terms of the Court as it is, rather than in terms of the Court as it was. In doing that I want to say something of who used to come to the Court, and how; and who come to the Court now, and how. And secondly I want to share with you some reflections on statements made in recent months by the Chief Justice of the High Court. Where High Court Judges Come From, and Certain Implications of That I turn to the belief and the practice and the proposal I mentioned. I remind you of three things. The first is that one still finds supposedly intelligent commentators making disapproving references to the practical monopoly which the practising Bar has over appointments to the High Court, and suggesting that the field of appointees ought to be extended to include solicitors and academics. The second is that, in line with the constitutional principle that a judge ought to have nothing to fear and nothing to hope for from the government which appointed him, there long existed a general practice of not promoting judges, within a system of courts run by the same government, either from court to court, or within a court, as by promotion to Chief Justice. -

The High Court of Australia: a Personal Impression of Its First 100 Years

—M.U.L.R— Mason— Title of Article — printed 14/12/03 at 13:17 — page 864 of 25 THE HIGH COURT OF AUSTRALIA: A PERSONAL IMPRESSION OF ITS FIRST 100 YEARS ∗ THE HON SIR ANTHONY MASON AC KBE [This article records my impressions of the High Court, its jurisprudence and the Justices up to the time when I became Chief Justice in 1987. For obvious reasons it would be invidious for me to record my impressions of the Court from that time onwards. The article reviews the work of the Court and endeavours to convey a picture of the contribution and personality of some of the individual Justices. The article concludes with the statement that the Court has achieved the high objectives of which Alfred Deakin spoke in his second reading speech on the introduction of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth). The Court has established its reputation as one of the world’s leading courts of final appeal and has fulfilled its role alongside the Parliament and the executive in our constitutional framework.] CONTENTS I Introduction.............................................................................................................864 II In the Beginning......................................................................................................865 III The Early High Court..............................................................................................866 IV Conflict with the Executive ....................................................................................867 V Conflict with the Privy Council ..............................................................................868 -

Judicial Stress and Judicial Bullying*

QUT Law Review Volume 14, Number 1, 2014 Special Edition: Wellness for Law JUDICIAL STRESS AND JUDICIAL BULLYING * THE HON MICHAEL KIRBY AC CMG** I JUDGES SUBJECT TO STRESS A national forum on wellness in Australian legal practice is timely. The growing attention to wellness in this context is welcome. Recent editions of professional journals in Australia and overseas bear witness to the increasing attention to, and concern about, stress, depression and pressure amongst law students1 and legal practitioners.2 The new-found attention is commendable. It was not always so. The change may have something to do with the increasing numbers of women entering the legal profession. On the whole, women appear more willing to speak about these formerly unmentionable topics than men. They do not so commonly feel inhibited, as men do, in recognising that wellness is not simply the absence of debilitating depression or feelings of abject failure. It may, or may not, be significant that the participants attending the Melbourne forum were overwhelmingly women: on my count, a proportion of more than four women attendees to one man. Many male lawyers still feel that talking about stress, pressure and depression is an admission of personal inadequacy or weakness. Or that it is embarrassing or irrelevant. They are afraid that they will be seen as ‘sooks’ or ‘cry-babies’. This is something men, from early childhood, have been told they must never be. As Neville Wran QC once famously observed in a political context: “Balmain boys don’t cry.” The equivalent professional motto seems to be: “Barristers don’t blub”; “Lawyers aren’t lachrymose.” We have to move beyond this. -

An Insight Into Appellate Justice in New South Wales

AN INSIGHT INTO APPELLATE JUSTICE IN NEW SOUTH WALES The Hon Justice MJ Beazley AO* President, New South Wales Court of Appeal Introduction 1 The earliest colonial judicial system in New South Wales was established by Letters Patent dated 2 April 1787,1 shortly prior to the First Fleet’s departure from England. The Letters Patent, known as the First Charter of Justice, established a Court of Civil Jurisdiction, to be constituted by the Deputy Judge-Advocate and two “fit and proper persons”, and a Court of Criminal Jurisdiction, to be constituted by the Deputy Judge-Advocate and six military personnel.2 2 The Letters Patent made provision for an appeal to the Governor, with a further right of appeal to the King in Council if more than 300 pounds was involved.3 It was nearly forty years later, in 1823, when the Charter of Justice established the Supreme Court of New South Wales and made it a court of record.4 The Charter named the first Chief Justice as Sir Francis Forbes, whom we now honour in this lecture series. 3 The Charter provided a limited right of appeal to the Privy Council from decisions of the New South Wales Court of Appeals – a body which Meagher, Gummow and Lehane point out was “a judicial body whose existence was *I wish to express my thanks to my Researchers, Hope Williams and Brigid McManus, for their research and assistance in the preparation of this paper. This paper was presented as the 2017 Francis Forbes Lecture, in the Banco Court of the Supreme Court of NSW, on 28 September 2017. -

Call for Donations-1

Portrait – Sir Kenneth Jacobs The Bar Association has commissioned a portrait of Sir Kenneth Jacobs to be donated to the Supreme Court of New South Wales and displayed in the President’s Court on Level 12 of the Law Courts Building. Sir Kenneth Jacobs is an honorary Life Member of the New South Wales Bar Association. He is a former President of the Court of Appeal and Justice of the High Court of Australia. The gift is a symbol of the great esteem and affection in which His Honour is held by the profession, especially here in New South Wales. Many members of the Association have already asked for an opportunity to make an individual donation towards the cost of the portrait. It is hoped to cover the full cost of the portrait by individual member donations. The names of those who donated to the cost will be suitably acknowledged when the gift is made to the Court. Once the full cost of the portrait is covered, an announcement will be made that no further donations from members are necessary. The artist is Ralph Heimans, a well known Australian portrait artist who painted the portrait of The Hon Justice Michael Kirby AC CMG that hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in Canberra. He has also painted a portrait of Chief Justice Christopher Langworth which hangs in the NSW Compensation Court and a portrait of Crown Princess Mary of Denmark displayed at the Royal National Portrait Gallery of Denmark in Copenhagen. Mr Heimans’ artwork may be viewed on his website at: http://www.ralphheimans.com/ Members may make a donation by forwarding a cheque, made out to the New South Wales Bar Association and addressed to the Association care of Corinne Brown at the Association’s address. -

T T) "T -T T L (/ L Contents

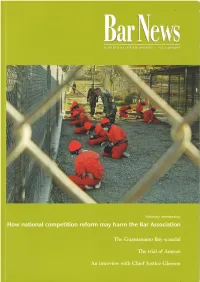

T t) "t -t t L (/ L Contents 1 Editor’s note 2 Letters to the Editor BarNewsThe JOURNAL of the NSW BAR ASSOCIATION 3 A message from the President Summer 2003/2004 4 Recent developments Mitchforce v Industrial Relations Commission Recent developments in family law Customs v Labrador Liquor Wholesale Pty Ltd ‘Marine adventure’: Gibbs v Mercantile Mutual Insurance (Australia) Ltd Editorial Board Relief against forfeiture Justin Gleeson SC (Editor) Andrew Bell 16 Opinion Rodney Brender Rena Sofroniou From the periphery to the centre: A new role for Indigenous rights Ingmar Taylor The Guantanamo Bay scandal Chris O’Donnell Response from the Commonwealth Attorney-General Chris Winslow (Bar Association) The trial of Amrozi 31 Features Design and Production Transitional justice: The prosecution of war crimes in Bosnia and Herzegovina Weavers Design Group www.weavers.com.au 36 Personalia A journey to the Persian Gulf Male liberation Advertising Bar News now accepts advertising. 42 Practice For information, visit www.weavers.com.au/barnews Voluntary membership: How national competition reform may harm the or contact John Weaver at NSW Bar Association Weavers Design Group The aspirational Bar: Sydney Downtown at [email protected] or English appeals court considers application to remove advocate from appearing phone 9299 4444 58 High Court centenary Interview with Chief Justice Murray Gleeson Cover Pride but not complacency Taliban and al-Qaeda detainees at Guantanamo Bay. Photo: AP/Shane T McCoy, US Navy. 67 Art 68 Book reviews 76 Cryptic crossword by Rapunzel ISSN 0817-002 77 Humour Views expressed by contributors to Bullfry and the Queens Square Blues Bar News are not necessarily those of the Bar Association of NSW.