Fachartikel "Psychogenic Urine Retention

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Addiction in Opioid Treatment Programs

Medication-Assisted Treatment For Opioid Addiction in Opioid Treatment Programs A Treatment Improvement Protocol TIP 43 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Center for Substance Abuse Treatment MEDICATION- www.samhsa.gov ASSISTED TREATMENT Medication-Assisted Treatment For Opioid Addiction in Opioid Treatment Programs Steven L. Batki, M.D. Consensus Panel Chair Janice F. Kauffman, R.N., M.P.H., LADC, CAS Consensus Panel Co-Chair Ira Marion, M.A. Consensus Panel Co-Chair Mark W. Parrino, M.P.A. Consensus Panel Co-Chair George E. Woody, M.D. Consensus Panel Co-Chair A Treatment Improvement Protocol TIP 43 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Center for Substance Abuse Treatment 1 Choke Cherry Road Rockville, MD 20857 Acknowledgments The guidelines in this document should not be considered substitutes for individualized client Numerous people contributed to the care and treatment decisions. development of this Treatment Improvement Protocol (see pp. xi and xiii as well as Appendixes E and F). This publication was Public Domain Notice produced by Johnson, Bassin & Shaw, Inc. All materials appearing in this volume except (JBS), under the Knowledge Application those taken directly from copyrighted sources Program (KAP) contract numbers 270-99- are in the public domain and may be reproduced 7072 and 270-04-7049 with the Substance or copied without permission from SAMHSA/ Abuse and Mental Health Services CSAT or the authors. Do not reproduce or Administration (SAMHSA), U.S. Department distribute this publication for a fee without of Health and Human Services (DHHS). -

Lodico of UR MG Public Comments August 7. 2015

Oral Fluid/Urine Proposed Mandatory Guidelines Federal Register Notices: Summary of Public Comments Presented by Charles LoDico, M.S., F-ABFT Division of Workplace Programs August 7, 2015 Drug Testing Advisory Board Federal Register Notices 2 • HHS published two Federal Register Notices on May 15, 2015 • Proposed revisions to the Mandatory Guidelines for Federal Workplace Drug Testing Programs using Urine (URMG); 94 FR 28101 • Proposed Mandatory Guidelines for Federal Workplace Drug Testing Programs using Oral Fluid (OFMG); 94 FR 28054 Public Comments 3 • HHS requested public comment on all aspects of the two Notices • Public comments were accepted until July 14, 2015 (60 days) at http://www.regulations.gov • HHS also specifically requested comment on certain items in the URMG and OFMG HHS URMG Specific Comments 4 • Change cutoff for pH adulterated • ≤ 4 and ≥ 11 • Requalification of MROs • Training and re-exam • 5 years after initial re-qualification URMG Public Comments 5 • 123 commenters • 427 comments • This includes comments relevant to urine that were submitted under the oral fluid FRN URMG Commenters 6 • 123 URMG commenters • 104 Individuals • 9 Professional organizations • 2 HHS-certified laboratories • 1 Collection site • 2 Employers • 5 MROs and/or TPAs Professional Organizations 7 • Airlines for America • Air Line Pilots Association, International • Association of Flight Attendants - CWA • American College of Occupational & Environmental Medicine • International Paruresis Association • National Safety Council • National School -

Statistical Analysis Plan

CONFIDENTIAL 2020N435253_00 The GlaxoSmithKline group of companies 206898 Division : Worldwide Development Information Type : Reporting and Analysis Plan (RAP) Title : Reporting and Analysis Plan for 206898: An Open Label, Phase 1 Study to Evaluate the PK, Safety, Tolerability and Acceptability of Long Acting Injections of the HIV Integrase Inhibitor, Cabotegravir (CAB; GSK1265744) in HIV Uninfected Chinese Men Compound Number : GSK1265744 Effective Date : 22-APR-2019 Description: The purpose of this RAP is to describe the planned analyses and output to be included in the Clinical Study Report for Protocol 206898. This RAP is intended to describe the safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetic (PK) analyses required for the study. This RAP will be provided to the study team members to convey the content of the Statistical Analysis Complete (SAC) deliverable. Author’s Name and Functional Area: PPD 22-APR-2019 Senior Biostatistician, PPD PPD 22-APR-2019 Pharmacokineticist (Biostatistics, PPD) Approved by: PPD 22-APR-2019 Statistics Leader, GSK PPD 22-APR-2019 Manager Statistics Copyright 2019 the GlaxoSmithKline group of companies. All rights reserved. Unauthorised copying or use of this information is prohibited. 1 CONFIDENTIAL 2020N435253_00 206898 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. REPORTING & ANALYSIS PLAN SYNOPSIS.........................................................5 2. SUMMARY OF KEY PROTOCOL INFORMATION ..................................................8 2.1. Changes to the Protocol Defined Statistical Analysis Plan ............................8 -

Toilet Phobia Booklet

National Phobics Society (NPS) Registered Charity No: 1113403 Company Reg. No: 5551121 Tel: 0870 122 2325 www.phobics-society.org.uk 1975 Golden Rail Award breaking the silence 1989 National Whitbread Community Care Award 2002 BT/THA Helpline Worker of the Year Award The Queen’s Award for Voluntary Service 2006 unsung heros The Queen’s Award for Voluntary Service 2006 what is toilet phobia? Toilet Phobia is rarely just one condition. It is a term used to describe a number of overlapping conditions (see diagram below): social what is toilet phobia? 3 phobia agoraphobia paruresis who can be affected? 4 toilet phobia what causes toilet phobia? 5 panic parcopresis does everyone have the same experience? 5 ocd forms of toilet phobia 6-7 real life experiences 8-12 These conditions have one thing in Due to the nature of this common - everyone affected has problem, people are often difficulties around using the toilet. reluctant to admit to the anxiety & fear: understanding the effects 13-14 These difficulties vary but with the condition or to seek help. right support, the problems can Those who do seek help can usually be alleviated, reduced or usually overcome or improve what types of help are available? 15-19 managed. their ability to cope with the problem, even after many The fears around the toilet include: years of difficulty. Seeking help real life experiences 20 • not being able to is the first step to finding real urinate/defecate improvements. success stories 21 • fear of being too far from a toilet • fear of using public toilets • fear that others may be watching your next step 22 or scrutinising/listening glossary 23 2 3 who can be affected? what causes toilet phobia? Almost anyone - Toilet Phobia is Toilet Phobia and overlapping/ not as rare as you may think. -

An Exploratory Investigation Into the Potential of Mobile Virtual Reality for the Treatment of Paruresis – a Social Anxiety Disorder J Lewis, a Paul, D Brown

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Nottingham Trent Institutional Repository (IRep) An Exploratory Investigation into the Potential of Mobile Virtual Reality for the Treatment of Paruresis – a Social Anxiety Disorder J Lewis, A Paul, D Brown Department of Computing, Nottingham Trent University Nottingham UK [email protected] www.ntu.ac.uk ABSTRACT This paper describes the initial exploratory phase of developing a VR intervention designed to alleviate the problems people with Paruresis experience when they need to utilise public toilet facilities. The first phase of the study produced a virtual environment, based upon a public toilet, which would run on the widely available Gear VR or Oculus Go HMD. The purpose of this prototype was to facilitate an informed discussion with a focus group of Paruresis patients, to obtain preliminary conclusions on whether they were interested in such an intervention and whether it offered potential to help alleviate the condition. In partnership with the UK Paruresis Trust the software was reviewed by both potential users and domain specialists. Results showed that the majority of participants reported a stress response to the stimulus of the virtual public toilet, indicating that it could be effective as a platform for graduated exposure therapy. Focus group feedback, and input from domain experts, was utilised as part of a participatory design methodology to guide the priorities for a second phase of development. The exploratory study concluded that this approach offers great potential as a future treatment for people with Paruresis 1. INTRODUCTION Paruresis is a specific type of social anxiety disorder, also known as Shy Bladder Syndrome. -

Psychological and Functional Disorder Co-Morbidities in Idiopathic Urinary Retention

Psychological and functional disorder co-morbidities in idiopathic urinary retention: International Consultation on Incontinence Research Society (ICI-RS) 2019 Running title: Psychological and functional disorder co-morbidities in urinary retention Jalesh N. Panicker1, Caroline Selai2, Francois Herve3, Kevin Rademakers4 Roger Dmochowski5, Tufan Tarcan6, Alexander von Gontard7, Desiree Vrijens8 1Department of Uro-Neurology, The National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery and UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology, London, United Kingdom 2Department of Clinical and Movement Neurosciences and Department of Uro-Neurology, The National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery and UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology, London, United Kingdom 3 Urology Department, Cliniques Universitaires Saint Luc, Brussels, Belgium 4 Department of Urology, Zuyderland Medical Centre, Sittard/Heerlen, Netherlands 5 Department of Urologic Surgery, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, USA 6 Department of Urology, Marmara University School of Medicine, Istanbul, Turkey 7Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Saarland University Hospital, 66121 Homburg, Germany 8Department of Urology, Maastricht University Medical Centre, Maastricht, The Netherlands Word count: 3250 Key word: Psychological disorders, anxiety, functional neurological symptom disorders, FND, somatization, urinary retention Corresponding author: Jalesh N. Panicker, Department of Uro-Neurology, The National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery and UCL Institute of Neurology, Queen Square, London WC1N 3BG, United Kingdom Email: [email protected] Telephone: +44(0)2034484713 Abstract Aims: Urinary retention occurring in young women is often poorly understood and a cause may not be found in a majority of cases despite an extensive search for urological and neurological causes. Different psychological co- morbidities and functional neurological symptom disorders (FNDs) have been reported in women with idiopathic urinary retention, however these have been poorly explored. -

The Provision of Public Toilets

House of Commons Communities and Local Government The Provision of Public Toilets Twelfth Report of Session 2007–08 Report, together with formal minutes, oral and written evidence Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 6 October 2008 HC 636 Published on 22 October 2008 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 Communities and Local Government Committee The Communities and Local Government Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Department for Communities and Local Government and its associated bodies. Current membership Dr Phyllis Starkey MP (Labour, Milton Keynes South West) (Chair) Sir Paul Beresford MP (Conservative, Mole Valley) Mr Clive Betts MP (Labour, Sheffield Attercliffe) John Cummings MP (Labour, Easington) Jim Dobbin MP (Labour Co-op, Heywood and Middleton) Andrew George MP (Liberal Democrat, St Ives) Mr Greg Hands MP (Conservative, Hammersmith and Fulham) Anne Main MP (Conservative, St Albans) Mr Bill Olner MP (Labour, Nuneaton) Dr John Pugh MP (Liberal Democrat, Southport) Emily Thornberry MP (Labour, Islington South and Finsbury) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publications The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including press notices) are on the Internet at www.parliament.uk/clgcom Committee staff The current staff of the Committee are Huw Yardley (Clerk of the Committee), David Weir (Second Clerk), Andrew Griffiths (Second Clerk), Sara Turnbull (Inquiry Manager), Josephine Willows (Inquiry Manager), Clare Genis (Committee Assistant), Gabrielle Henderson (Senior Office Clerk), Nicola McCoy (Secretary) and Laura Kibby (Select Committee Media Officer). -

Guideline Appendix I

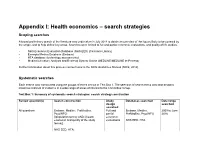

Appendix I: Health economics – search strategies Scoping searches A broad preliminary search of the literature was undertaken in July 2014 to obtain an overview of the issues likely to be covered by the scope, and to help define key areas. Searches were limited to full and partial economic evaluations, and quality of life studies. • NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED) [Cochrane Library] • Excerpta Medica Database (Embase) • HTA database (technology assessments) • Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE/MEDLINE In-Process) Further information about this process can be found in the NICE Guidelines Manual (NICE, 2014). Systematic searches Each search was constructed using the groups of terms set out in Text Box 1. The selection of search terms was kept broad to maximise retrieval of evidence in a wide range of areas of interest to the Committee Group. Text Box 1: Summary of systematic search strategies: search strategy construction Review question(s) Search construction Study Databases searched Date range design searched searched All questions Embase, Medline, PreMedline, Full and Embase, Medline, 2000 to June PsycINFO: partial PreMedline, PsycINFO 2016 [(population terms) AND [(health economic economic and quality of life study evaluations NHS EED, HTA terms)] NHS EED, HTA: [(population terms)] Systematic searches Databases: Embase, Medline, PreMedline, PsycINFO – OVID Dates searched: 2000 to June 2016 # searches court/ or crime/ or criminal behavior/ or criminal justice/ or criminal law/ or custody/ or 1 -

United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit Chicago, Illinois 60604

NONPRECEDENTIAL DISPOSITION To be cited only in accordance with Fed. R. App. P. 32.1 United States Court of Appeals For the Seventh Circuit Chicago, Illinois 60604 Submitted November 6, 2015* Decided November 9, 2015 Before WILLIAM J. BAUER, Circuit Judge JOEL M. FLAUM, Circuit Judge DAVID F. HAMILTON, Circuit Judge No. 15-1082 JONATHAN D. WILKE, Appeal from the United States District Plaintiff-Appellant, Court for the Eastern District of Wisconsin. v. No. 12-CV-1231-JPS CHARLES E. COLE, et al., J.P. Stadtmueller, Defendants-Appellees. Judge. O R D E R Jonathan Wilke, a former Wisconsin inmate now in federal custody, contends that the defendants, all of them employed by the Department of Corrections, did not respond appropriately to his paruresis, a type of social phobia that makes it difficult to urinate in the presence of others. See American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 300.23 (5th ed. 2013). Wilke characterized his paruresis as both a serious medical need and a disability. The defendants, he claimed, had been deliberately indifferent to the condition in violation of the Eighth Amendment, and also * After examining the briefs and record, we have concluded that oral argument is unnecessary. Thus the appeal is submitted on the briefs and record. See FED. R. APP. P. 34(a)(2)(C). No. 15-1082 Page 2 had failed to accommodate his phobia in violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act, see 42 U.S.C. § 12132. The district court dismissed the Eighth Amendment claim at screening, see 28 U.S.C. -

EMDR Therapy Evaluated Clinical Applications Page 1 of 19 Updated 2019-02

EMDR Therapy Evaluated Clinical Applications page 1 of 19 updated 2019-02 EMDR THERAPY EVALUATED CLINICAL APPLICATIONS To-date, while numerous randomized controlled studies have supported EMDR therapy’s effectiveness in the treatment of trauma and PTSD across the lifespan, other clinical applications are generally evaluated in case studies, open trials and isolated RCT and are in need of further investigation. In addition to the studies reviewed in Chapter 12, this section provides an overview of a range of published evaluations. Another excellent resource is the Francine Shapiro Library (FSL) created by Barbara Hensley, Ed.D., and hosted by the EMDR International Association. It is a compendium of scholarly articles and other significant publications related to the Adaptive Information Processing model and EMDR therapy. http://emdria.omeka.net/ Since the initial efficacy study (Shapiro, 1989a), positive therapeutic results with EMDR therapy have been reported with a wide range of populations including the following: 1. Combat veterans from the Iraq Wars, the Afganistan War, the Vietnam War, the Korean War, and World War II who were formerly treatment resistant and who no longer experience flashbacks, nightmares, and other PTSD sequelae (Blore, 1997a; Brickell, Russell, & Smith, 2015; Carlson, Chemtob, Rusnak, & Hedlund, 1996; Carlson, Chemtob, Rusnak, Hedlund, & Muraoka, 1998; Daniels, Lipke, Richardson, & Silver, 1992; Hurley, 2018; Lansing, 2013; Lipke, 2000; Lipke & Botkin, 1992; McLay et al, 2016; Narimani, Sadeghieh Ahari, & Rajabi, 2008; Niroomandi, 2012; Russell, 2006, 2008b; Russell & Figley, 2012; Russell, Silver, Rogers, & Darnell, 2007; Silver & Rogers, 2001; Silver, Rogers, & Russell, 2008; Thomas & Gafner, 1993; Wesson & Gould, 2009; Wright & Russell, 2012; White, 1998; Young, 1995;). -

Acute Water Intoxication During Military Urine Drug Screening

MILITARY MEDICINE, 176, 4:451, 2011 Acute Water Intoxication During Military Urine Drug Screening Maj Molly A. Tilley , USAF MC ; Maj Casey L. Cotant , USAF MC ABSTRACT Random mandatory urine drug screening is a routine practice in the military. The pressure to produce a urine specimen creates a temptation to consume large volumes of water, putting those individuals at risk of acute water intoxication. This occurs when the amount of water consumed exceeds the kidney’s ability to excrete it, resulting in hyponatremia owing to excess amount of water compared to serum solutes. The acute drop in serum osmolality leads to cerebral edema, causing headaches, confusion, seizures, and death. There has been increasing awareness of the danger of overhydration among performance athletes, but dangers in other groups can be underappreciated. We present the case Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/milmed/article/176/4/451/4345329 by guest on 23 September 2021 of a 37-year-old male Air Force offi cer who developed acute water intoxication during urine drug screening. Our case demonstrates the need for a clear Air Force policy for mandatory drug testing to minimize the risk of developing this potentially fatal condition. INTRODUCTION lying on his back in the rest room, restless, and inarticulate. Acute and chronic hyponatremia are common disorders that Intravenous normal saline was started and the patient was are associated with adverse clinical outcomes.1 Typically, acute monitored by telemetry. He had a normal sinus rhythm, with hyponatremia is encountered in the hospitalized patient with blood pressure of 140/62 and heart rate of 97. -

Deturtm (Desensitization of Triggers and Urge Reprocessing) a New Approach to Working with Addictions and Dysfunctional Behaviors and the Underlying Traumas Arnold J

DeTURTM (Desensitization of Triggers and Urge Reprocessing) A New Approach to Working with Addictions and Dysfunctional Behaviors and the underlying Traumas Arnold J. Popky, Ph.D., MFT 5759 Hazeltine Ave. Sherman Oaks, CA 91401 (818-908-8940 EMAIL: [email protected] AJPOPKY-EMDR.COM Copyright © 2007 by A. J. Popky This eclectic treatment model and the theories involved are based solely on experience from personal client observation and anecdotal reports received from other therapists using this same protocol. It is an eclectic model and combines many methodologies, including but not limited to, cognitive-behavioral, solution focused, Ericksonian, narrative, object relations, NLP, The AIP model of EMDR, etc. The bi-lateral stimulation seems to form the catalyst for rapid processing and change, the turbo-charger that speeds the healing process. Successful results have been reported across the spectrum of addictions and dysfunctional behaviors: chemical substances (nicotine, marijuana, alcohol, methamphetamine, cocaine, crack, heroin/methadone, etc.), eating disorders such as compulsive overeating, anorexia and bulimia, along with other behaviors such as sex, gambling, shoplifting, anger outbursts, and trichotillomania, etc. As new information becomes available, it is incorporated into the protocol. This protocol only represents a small part of a complete treatment model. The therapist role is that of a case manager, orchestrating any/all resources necessary to aid the patient through recovery to a successful and healthy state of functioning and coping. The therapist must be able to assess severity of the addiction and determine any other diagnosis associated with the case. This model includes referrals for, medication, and testing for physical or neurological problems.