Golden Patents, Empty Pockets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Avalanche Information for Subscribers

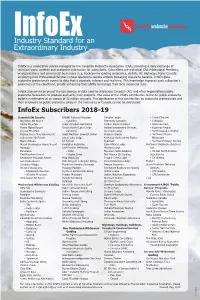

InfoEx Industry Standard for an Extraordinary Industry InfoEx is a cooperative service managed by the Canadian Avalanche Association (CAA), providing a daily exchange of technical snow, weather and avalanche information for subscribers. Subscribers are individual CAA Professional Members, or organizations and commercial businesses (e.g. backcountry guiding companies, ski hills, BC Highways, Parks Canada) employing CAA Professional Members whose operations require actively managing avalanche hazards. InfoEx gives avalanche professionals access to data that is accurate, relevant and real time. This knowledge improves each subscriber’s awareness of the conditions, greatly enhancing their ability to manage their local avalanche risks. InfoEx also serves as one of the key sources of data used by Avalanche Canada’s (AC) and other organizations public avalanche forecasters to produce and verify their products. The value of the InfoEx contribution to the AC public avalanche bulletin is estimated at an excess of $2 million annually. The significance of this contribution by avalanche professionals and their employers to public avalanche safety in the mountains of Canada cannot be overstated. InfoEx Subscribers 2018-19 Downhill Ski Resorts KPOW! Fortress Mountain Dezaiko Lodge • Coast/Chilcotin Big White Ski Resort Catskiing Extremely Canadian • Columbia Castle Mountain Great Canadian Heli-Skiing Golden Alpine Holidays • Kootenay Pass Fernie Alpine Resort Gostlin Keefer Lake Lodge Hyland Backcountry Services • Kootenay Region Grouse Mountain Catskiing Ice Creek Lodge • North Cascades District Kicking Horse Mountain Resort Great Northern Snowcat Skiing Kokanee Glacier • Northwest Region Lake Louise Ski Resort Island Lake Lodge Kootenay Backcountry Guides Ningunsaw Marmot Basin K3 Cat Ski Kyle Rast • Northwest Region Terrace Mount Washington Alpine Resort Kingfisher Heliskiing Lake O’Hara Lodge Northwest Avalanche Solutions Norquay Last Frontier Heliskiing Mistaya Lodge Ltd. -

CP's North American Rail

2020_CP_NetworkMap_Large_Front_1.6_Final_LowRes.pdf 1 6/5/2020 8:24:47 AM 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Lake CP Railway Mileage Between Cities Rail Industry Index Legend Athabasca AGR Alabama & Gulf Coast Railway ETR Essex Terminal Railway MNRR Minnesota Commercial Railway TCWR Twin Cities & Western Railroad CP Average scale y y y a AMTK Amtrak EXO EXO MRL Montana Rail Link Inc TPLC Toronto Port Lands Company t t y i i er e C on C r v APD Albany Port Railroad FEC Florida East Coast Railway NBR Northern & Bergen Railroad TPW Toledo, Peoria & Western Railway t oon y o ork éal t y t r 0 100 200 300 km r er Y a n t APM Montreal Port Authority FLR Fife Lake Railway NBSR New Brunswick Southern Railway TRR Torch River Rail CP trackage, haulage and commercial rights oit ago r k tland c ding on xico w r r r uébec innipeg Fort Nelson é APNC Appanoose County Community Railroad FMR Forty Mile Railroad NCR Nipissing Central Railway UP Union Pacic e ansas hi alga ancou egina as o dmon hunder B o o Q Det E F K M Minneapolis Mon Mont N Alba Buffalo C C P R Saint John S T T V W APR Alberta Prairie Railway Excursions GEXR Goderich-Exeter Railway NECR New England Central Railroad VAEX Vale Railway CP principal shortline connections Albany 689 2622 1092 792 2636 2702 1574 3518 1517 2965 234 147 3528 412 2150 691 2272 1373 552 3253 1792 BCR The British Columbia Railway Company GFR Grand Forks Railway NJT New Jersey Transit Rail Operations VIA Via Rail A BCRY Barrie-Collingwood Railway GJR Guelph Junction Railway NLR Northern Light Rail VTR -

Residents Guide

General Reference Guide for CASTLE MOUNTAIN RESORT Updated April 2018 1 THE CORPORATION - Castle Mountain Resort .............................................................................................................. 3 THE COMMUNITY - Castle Mountain Community Association .................................................................................. 4 THE MD OF PINCHER CREEK ............................................................................................................................................. 5 Castle Provincial ParKs ................................................................................................................................................................... 5 EMERGENCY SERVICES ...................................................................................................................................................... 6 PARKING AND MAPS ......................................................................................................................................................... 7 Figure 1: Winter Village Area Map .............................................................................................................................................. 8 Figure 2: West Castle Valley Winter Multi-Use Trails .............................................................................................................. 9 Figure 3: Summer Hiking Trail Guide ........................................................................................................................................ -

United States Geological Survey Charles D

Bulletin No. 218 Series A, Economic Geology, 26 DEPARTMENT OF TPIE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES D. WALCOTT, DIRECTOR THE BY ARTI-IUR J. COLLIER- WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1903 UJ <" tf 0(£l r CONTENTS. _ Page. Letter of transmittalT^ .................................................... 7 Introduction.......... ................................................... 9 Geography. ...... .^...................................................... 11 Sketch of geology ........................................................ 13 The coal..............................................................:... 19 Geographic distribution and.character................................. 19 Descriptions of localities .............................................. 20 Introduction..................................................... 20 Circle province..............................................'..... 20 Coul in Canadian territory .................................... 21 Mission Creek.............................. J................. 26 Seve'ntymile River............................................ 28 Washington Creek............................................ 28 Bonanza Creek............................................... 32 Coal Creek................................................... 32 Nation River mine............................................ 33 Rampart province......:......................................... 36 Drew mine ..............................................\... 37 Minook Creek............................................... -

Winter Trails in the Lake Louise Area

Cross-Country Ski Trails Hiking and Snowshoeing Trails You Are In A Special Place TRAILS IN LAKE LOUISE (See Map A) 9 9 Bow River Loop TRAILS IN LAKE LOUISE (See Map A) Lake Louise SAFETY CONSIDERATIONS 6.6 km or shorter versions of the loop, no elevation gain. Safety is your responsibility. There are always hazards involved 1 1 Moraine Lake Road 14 Lake Louise Lakeshore Winter Trails in the Single trackset with outdoor recreational activities, especially during the 15.6 km return, 250 m elevation gain. 4 km return, no elevation gain. winter. Be prepared. Even short trips around the village of Lake Mostly flat, following the river. To start, park near the Station Lake Louise Area Double trackset with skating lane Louise can have serious consequences. Minimize your risk by Restaurant or just past the campground kiosk, or use the Starting in front of the Chateau Lake Louise, this trail features planning ahead. Climbing steadily, this trail includes both gently rolling and connecting trail from the Post Hotel or the Samson Mall. This classic views and at lake’s end, a 100 m tall frozen waterfall. hilly stretches. Tracksetting ends at a viewpoint of Consolation is a multi-use trail. • Ask for advice at the Lake Louise Visitor Centre regarding Valley and the Ten Peaks. Beyond the viewpoint, the road 15 Fairview Lookout current trail conditions, weather and trail classifications. crosses large avalanche paths. 10 Campground Loop 2 km return, 100 m elevation gain. • Check the trail reports online pc.gc.ca/trails. The trail 2.2 km outer loop, 15 m elevation gain. -

Banff National Park

to Town of Jasper (233 km from Lake Louise, 291 km from Banff) WHITE GOAT JASPER D. ICEFIELDS PARKWAY (#93N) NATIONAL Nigel Pass This is one of the world’s greatest mountain highroads, JASPER PARK WILDERNESS AREA (p. 20,21) named for the chain of huge icefields that roofs the Rockies. NATIONAL COLUMBIA Sixty years ago, a trip from Lake Louise to Jasper took two PARK 12 weeks by pack horse. Now you can travel the 230 km in a British Athabasca NORTH day, with time to stop at points of interest (#7-11). Be Jasper Alberta ICE- FIELDS Columbia prepared for varied weather conditions; snow can fall in the Sunset Pinto Lake high passes even in midsummer. Jasper Saskatchewan Pass Yoho Banff David Kootenay SASKATCHEWAN River Thompson 13 Highway to Amery Rocky Mountain Wilson House (174km) Alexandra 11 93 N. SASKATCHEWAN RIVER ALBERTA RIVER Saskatchewan 11 01020 30 Lyle Crossing Kilometres Erasmus SIFFLEUR Miles BANFF 0 5 10 15 BRITISH WILDERNESS COLUMBIA YOHO NATIONAL Glacier Lake 10 N.P. Howse Lake Louise Sarbach Siffleur Field AREA PARK 2 Campgrounds Banff Forbes River Chephren Points of interest Icefall Canmore 9 (p.16) Chephren Malloch Coronation Lake 12 River KOOTENAY APM Automated Howse Pass Noyes River N.P. pass machine (p.10) Dolomite Hostel Mistaya ICEFIELDS Tomahawk Clearwater Lake Clearwater Radium Accommodation Freshfield River Peyto Creek For up-to-the-minute Visitor Centre Lake 9 ? park and weather Trail Katherine information, tune in to Blaeberry Lake River the Banff Park radio Bow L. Red Deer McConnell station: 101.1FM. 8 C. -

Banff National Park Alberta

BANFF NATIONAL PARK ALBERTA On the Banff-Jasper Highway GENERAL INFORMATION AND MAP DEPARTMENT OF MINES AND RESOURCES LANDS, PARKS AND FORESTS BRANCH NATIONAL PARKS BUREAU OTTAWA, CANADA Lakes National Park, and thence over Provincial Highways Following is a list of hotels, lodges, and bungalow camps Public camp-grounds, less completely equipped than that at Banff, BANFF NATIONAL PARK are situated at Johnston Canyon, 16 miles; Castle Mountain, 20 miles; 6, 3, 2, and 1, via Pincher, Macleod, and Calgary. in the park with rates per day:— Lake Louise. 40 miles; Moraine Lake, 47 miles from Banff; and on Banff- Following are distances from the town of Banff to well Jasper Highway at Mosquito Creek (mile 53 from Banff); Bow Pass Banff— Accommodation Rates (mile 64); Waterfowl Lakes (mile 75); Saskatchewan River (mile 89); ALBERTA known points:— *Banff Springs Hotel.. .600 rooms Single $6.50 up; double $10 up (Eur.) and The Castelets (mile 103 from Banff). Lake Louise, 40 miles; Field, 56 miles; Golden, 92 miles; (C.P.R.) Revelstoke, 285 miles (via Big Bend); Vancouver, 729 miles Cascade Hotel 45 rooms Single $1-$1.50; double $2—$2.50 RECREATION (Eur.) (via Big Bend); Jasper, 186 miles (via Banff-Jasper High •Homestead Hotel 50 rooms Single $1.50; double $2 (Eur.) Bathing and Swimming.—Outdoor bathing may be way); Calgary, 85 miles; Edmonton, 276 miles; Elk Island PURPOSE OF NATIONAL PARKS Hot Springs Hotel. ... 22 rooms Single $3; per week $17.50 (Amer.) enjoyed at Banff at the Cave and Basin and Upper Hot Park, 302 miles; Lethbridge, 224 miles; Waterton Lakes King Edward Hotel. -

Nicholas Morant Fonds (M300 / S20 / V500)

NICHOLAS MORANT FONDS (M300 / S20 / V500) I.A. PHOTOGRAPHY SERIES : NEGATIVES AND TRANSPARENCIES 1.b. Darkroom files : black and white A-1. Noorduyn aircraft. -- [between 1930 and 1980]. -- 7 photographs : negatives, film, b/w, 6x6 cm. -- Geographic region: Canada. -- Storage location: V500/A2/A-1. A-2. High altitude vapor tracks. -- [between 1930 and 1980]. -- 2 photographs : negatives, film, b/w. -- 7.5x10cm or smaller. -- NM note: air tracks. -- Geographic region: Canada. -- Storage location: V500/A2/A-2. A-3. Montage air stuff featuring Harvards at Uplands mostly. -- [between 1930 and 1980]. -- 25 photographs : negatives, film, b/w. -- Ottawa airport. -- 7.5x10cm or smaller. -- Geographic region: Ontario. -- Storage location: V500/A2/A-3. A-4. R.A.F. Ferry command, Dorval. -- Storage location: missing on acquisition A-5. C.P. Airlines aerial shots. -- [between 1930 and 1980]. -- 6 photographs : negatives, film, b/w. -- Canadian Pacific Airlines. -- 7.5x10cm or smaller. -- NM note: very early shots; first Yukon southern delivery. -- Geographic region: Yukon. -- Storage location: V500/A2/A-5. A-6. Pacific coast vigil. -- [ca.1940]. -- 2 photographs : negatives, film, b/w. -- 7.5x10cm or smaller. -- NM note: army on west coast. -- Geographic region: British Columbia. -- Storage location: V500/A2/A-6. A-7. Alaskan mountains for montage. -- [between 1930 and 1980]. -- 3 photographs : negatives, film, b/w. -- 7.5x10cm or smaller. -- Geographic region: United States. -- Storage location: V500/A2/A-7. A-9. Boeing, Vancouver, on Catalinas. -- [between 1930 and 1980]. -- 8 photographs : negatives, film, b/w. -- 7.5x10cm or smaller. -- Geographic region: British Columbia. -- Storage location: V500/A2/A-9. -

Connect with the Truly Canadian in Banff National Park - Banff and Lake Louise the Ultimate Canadian Getaway

Connect with the Truly Canadian in Banff National Park - Banff and Lake Louise the Ultimate Canadian Getaway - Caption: Visitors demonstrate Canadian pride at Lake Louise. June 25, 2020 (BANFF & LAKE LOUISE, ALBERTA) – Canada Day is usually celebrated with parades and shows, but mark Canada Day 2020 with a celebration of Banff National Park’s natural beauty and unique experiences available to visitors this summer. There are plenty of ways to celebrate national pride in Canada’s first national park, safely and with plenty of physical distancing. And this year, with Canada Day falling on a Wednesday, it’s the perfect excuse to extend the holiday to the weekend before or after Canada Day in Banff National Park. Canadians can embrace Banff’s lively atmosphere and mountain vistas from car-free Banff Avenue, which hasn’t closed to vehicles for more than two days since 2008. The closure of the 100 to 200 blocks of Banff Avenue means more space for pedestrians to explore, eat and shop safely downtown this summer. Enjoy your meal outside at one of Banff’s great restaurants with plenty of added outdoor seating. Visitors can fuel up for a day of adventure at one of Banff’s newest restaurants in the heart of town. Wood-fired and slow-roasted staples can be enjoyed at Farm and Fire’s open and airy restaurant, while a dynamic menu of shareables can be savoured at The Radiant. From squeaky poutine at Banff Poutine, to delectable desserts from Beavertails and prime Alberta Beef at Chuck’s Steak House, take your pick on where to eat your fill of Canadian favourites. -

The Stratigraphic Section in the Vicinity of Eureka, Nevada

The Stratigraphic Section in the Vicinity of Eureka, Nevada GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 276 The Stratigraphic Section in the Vicinity of Eureka, Nevada By T. B. NOLAN, C. W. MERRIAM, and J. S. WILLIAMS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 276 Revision of the pre- Tertiary stratigraphy of east-central Nevada UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1956 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Douglas McKay, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. E. Wrather, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. - Price $1.00 (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Page Abstract_ _____________________ 1 Silurian system.___________________________ 36 Introduction. _--___-______--___- 2 Roberts Mountains formation.__________ 36 Acknowledgments- --.-_---___-_-. 3 Lone Mountain dolomite__________... 37 Structural setting._______________ 3 Devonian system.__________-_-_-__--_____. 40 Economic significance. _-__._. 5 Nevada formation_________--______--. 40 Cambrian system.________________ 5 Beacon Peak dolomite member. 42 Prospect Mountain quartzite.. 6 Oxyoke Canyon sandstone member... 43 Pioche shale_______--_-_-_.__. 7 Sentinel Mountain dolomite member. 43 Eldorado dolomite___________ 9 Woodpecker limestone member. 44 Geddes limestone.___________ 11 Bay State dolomite member.--...--. 45 Secret Canyon shale._________ 12 Devils Gate limestone._________________ 48 Lower shale member. .... 13 Meister member.__________________ 49 Hayes Canyon member.____________ 49 Clarks Spring member.._ 14 Devonian and Mississippian systems. ________ 52 Hamburg dolomite.___-_.____ 16 Pilot shale________-__-_-___--__---_-_. 52 Dunderberg shale.___________ 18 Carboniferous systems_.____-__-______-__- 54 Windfall formation.__________ 19 Mississippian system._________--,___-_- 54 Catlin member._________ 20 Joana limestone,___________________ 54 Bullwhacker member. -

Glaciers of the Canadian Rockies

Glaciers of North America— GLACIERS OF CANADA GLACIERS OF THE CANADIAN ROCKIES By C. SIMON L. OMMANNEY SATELLITE IMAGE ATLAS OF GLACIERS OF THE WORLD Edited by RICHARD S. WILLIAMS, Jr., and JANE G. FERRIGNO U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1386–J–1 The Rocky Mountains of Canada include four distinct ranges from the U.S. border to northern British Columbia: Border, Continental, Hart, and Muskwa Ranges. They cover about 170,000 km2, are about 150 km wide, and have an estimated glacierized area of 38,613 km2. Mount Robson, at 3,954 m, is the highest peak. Glaciers range in size from ice fields, with major outlet glaciers, to glacierets. Small mountain-type glaciers in cirques, niches, and ice aprons are scattered throughout the ranges. Ice-cored moraines and rock glaciers are also common CONTENTS Page Abstract ---------------------------------------------------------------------------- J199 Introduction----------------------------------------------------------------------- 199 FIGURE 1. Mountain ranges of the southern Rocky Mountains------------ 201 2. Mountain ranges of the northern Rocky Mountains ------------ 202 3. Oblique aerial photograph of Mount Assiniboine, Banff National Park, Rocky Mountains----------------------------- 203 4. Sketch map showing glaciers of the Canadian Rocky Mountains -------------------------------------------- 204 5. Photograph of the Victoria Glacier, Rocky Mountains, Alberta, in August 1973 -------------------------------------- 209 TABLE 1. Named glaciers of the Rocky Mountains cited in the chapter -

Vacation-Planner.Pdf

www.banffinfo.com Local 403 762 0260 Toll free 1877 226 3348 1 Welcome to the beautiful Canadian Rockies For the past 10 years our company has been organizing vacations for our clients travelling to the beautiful Canadian Rockies. Our team of local agents are located in Banff, Alberta and are dedicated solely to organizing custom made vacations. The Canadian Rockies is where we live and is our speciality. While the technology of the internet has brought much more information easily to people, many still just don’t have the time to sit and browse through the multitude of options available, or are confused by the conflicting reviews on user forums, like TripAdvisor. We thought it would be helpful to put together an online guide to make planning your vacation easier and quicker. This guide is also meant as a checklist so you don’t miss out on any major highlights. We have compiled our most popular itineraries which A Guide to include all the major highlights. your All these itineraries can be booked ‘as is” or can be used as the basis for a customized vacation. You can mix and match any of the hotels and tours on the Banff Canadian Accommodation Reservations website to design a holiday that suits your personal Rockies interests and budget. Vacation To keep the size of this file to a minimum, we have hyperlinked (blue text) to various pages in our website for current pricing and detailed information. How to go about planning your vacation The area is quite large and a common mistake is trying to cover too much with not enough time.